This past Fourth of July weekend, Michael Twitty detailed the often-forgotten influence of enslaved Africans on U.S. barbecue in his article in The Guardian. “At best, our ancestors are seen as mindless cooking machines who prepared the meat under strict white supervision, if at all; at worst, barbecue was something done ‘for’ the enslaved, as if they were being introduced to a novel treat,” Twitty wrote. “In reality, they shaped the culture of New World barbecuing traditions.” Giving slaves credit for shaping what we know as Southern barbecue quickly became a flash point, and the bigoted comments flowed like vinegar on a whole hog in the Carolinas.

Texas barbecue, like Texas itself, has many origins. South Texas is influenced by Mexico, especially in the barbacoa realm. German and Czech butchers built our most famous style of barbecue in Central Texas’s meat markets, and in the Hill Country they still use what they refer to as “Dutch” or “German” pits lit by coals directly under the meat. But the origins of East Texas barbecue, heavily influenced by the slave population, aren’t nearly as well documented or celebrated, even though the tradition dates back to long before anything in Austin.

The formation of the East Texas style, or really any barbecue style in the South, didn’t begin until the rise of barbecue restaurants after the Civil War. I’ll get to that important transformation in East Texas in a future column, but for now let’s focus on how Southern barbecue, as it was practiced before the Civil War, made it into Texas in the first place. Before there were restaurants, there was still plenty of barbecue in the Lone Star State, but it was mostly community-wide endeavors centered around a special occasion. And most of those celebrations happened east of present-day I-35. That’s where all the people were, after all, and it’s where all the slaves were too.

Barbecue was a shared tradition among slaves, and unlike the distinct regional ‘cues we see today, the differences throughout the antebellum South hinged only on what type of wood and animals were available. So it’s no surprise that we’d see cooking methods that were cemented in the plantations of Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas make their way into East Texas with the influx of slaves just before the Civil War.

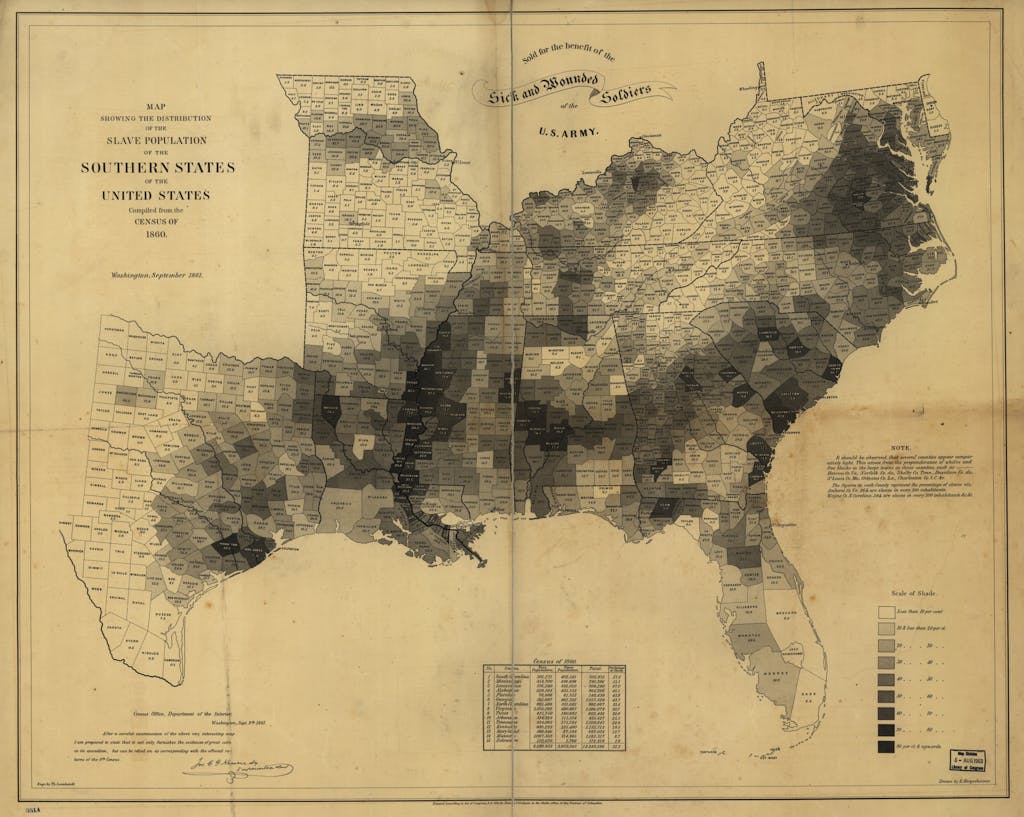

In 1835, just before Texas independence, there were 5,000 slaves in Texas, brought by American settlers despite the fact that Mexican law barred slavery. Once the state earned its independence, the following year, slavery was made legal, and in 1845 Texas was annexed to the United States as a slave state. “By 1840, 13,000 African Americans were enslaved in Texas. By 1850, 48,000 were enslaved, and by 1860, 169,000—30 percent of the Texas population,” according to the Handbook of Texas. By 1860, slaves made up more than half the population of fourteen counties in East Texas. In Wharton County it was 81 percent. And wherever they were forced to settle, slaves brought their barbecue traditions with them.

Frederick Douglass Opie’s book Hog and Hominy traces the origin of soul food from Africa to the U.S. Like Twitty, Opie highlighted similar African cooking styles: “African women cooked most meats over an open pit and ate them with a sauce similar to what we now call a barbecue sauce, made from lime or lemon juice and hot peppers.”

Opie also points out that Southern slaves “came from regions where they barbecued on feast days. Thus barbecuing was another African technique that they had to adapt to the ingredients available to them as enslaved African cooks on white-owned plantations.” The Fourth of July has become the height of barbecue season in the U.S., but it was also one of the few days in the year when Southern slaves were able to celebrate.

Festivities are mentioned repeatedly in slave narratives recorded by the WPA from 1936 to 1938, and with little documentation of black contributions to barbecue coming from white newspapers, these candid interviews are one of the best resources for understanding what life on a plantation was like for slaves. Willis Cofer from Georgia explained to an interviewer (spelling from the transcript): “Evvy plantation gen’ally had a barbecue and big dinner for Fourth of July, and when sev’ral white families went in together, dey did have high old times tryin’ to see which one of ‘em could git deir barbecue done and ready to eat fust.”

Louis Hughes penned a detailed account of such a celebration in his 1896 book, Thirty Years a Slave. “Barbecue originally meant to dress and roast a hog whole, but has come to mean the cooking of a food animal in this manner for the feeding of a great company,” Hughes explained. “A feast of this kind was always given to us, by Boss, on the 4th of July.” And by “given to us,” Hughes meant they ate it—but only after they prepared everything.

The day before the 4th was a busy one. The slaves worked with all their might. The children who were large enough were engaged in bringing wood and bark to the spot where the barbecue was to take place. They worked eagerly, all day long; and, by the time the sun was setting, a huge pile of fuel was beside the trench, ready for use in the morning. At an early hour of the great day, the servants were up, and the men whom Boss had appointed to look after the killing of the hogs and sheep were quickly at their work…they never lost sight of the trench or the spot where the sweetmeats were to be cooked.

The method of cooking the meat was to dig a trench in the ground about six feet long and eighteen inches deep. This trench was filled with wood and bark which was set on fire, and, when it was burned to a great bed of coals, the hog was split through the back bone, and laid on poles which had been placed across the trench. The sheep were treated in the same way, and both were turned from side to side as they cooked. During the process of roasting the cooks basted the carcasses with a preparation furnished from the great house, consisting of butter, pepper, salt and vinegar, and this was continued until the meat was ready to serve.

In his account, the slaves on this Mississippi plantation dug the trench, gathered the fuel, slaughtered the animals, and then cooked them on the pit—and this was their day off. They were the pitmasters, but they didn’t get their first choice of meat, as Hughes recalls. “Some of the nicest portions of the meat were sliced off and put on a platter to send to the great house for Boss and his family.”

This goes counter to the old story (one that I, unfortunately, perpetuated in my book The Prophets of Smoked Meat) that slaves learned to cook the off-cuts because that’s all they were given. That’s not really true. The slave narratives help to enlighten us on this subject as well. Besides celebration days, any protein was either from game hunting or the slave’s weekly rations. But they weren’t given leftover or spoiled cuts of meat. It was usually some form of preserved meat like bacon. Gus Johnson of Beaumont, Texas, described his rations (which echoed accounts from many others) on an Alabama plantation in his WPA interview. “Dey give us rations on Saturday and dat’s ’bout five pound salt bacon and a peck of meal and some sorghum syrup.” These weren’t off-cuts of meat that made it on a barbecue pit. When barbecue was cooked in the antebellum South, it was done as whole animals. The boss’s house may have gotten their choice cuts from the finished product, but individual cuts weren’t divvied up prior. When it came to barbecue, slaves were masters of whole animal cooking.

In his recent book, A History of South Carolina Barbeque, Lake High Jr. takes issue with slaves’ influence on the art. “Blacks were certainly not the inventors of barbeque,” he explains. “The problem was that all northern writers saw barbeque as a black food because every time they got their hands on some it had come from black cooks. Barbeque became linked to blacks in the minds of northern writers.” I’m not saying the slaves were the sole inventors of Southern barbecue. That would leave out the well-documented role that Native Americans played, but the contribution of the slaves needs some acknowledgement and High gives them none.

High describes barbecue as a practical skill. “[Slaves] learned to cook barbeque in the same way they learned to become cabinetmakers or blacksmiths: somebody needed the job done and showed them how to do it,” High wrote. He then tries to take the sting out of the statement with a backhanded compliment: “Since food is loved by all and many blacks are naturally good cooks, they took to the art of barbeque quickly and well.”

Here’s the problem with that theory: barbecues were a special occasion. Unlike blacksmiths and cabinet makers, a plantation owner wouldn’t need a well-trained pitmaster but once or twice a year, and the cooking being done was largely to benefit the slaves. Why would a plantation owner waste the time passing on the specialized skill of cooking meat on a pit when the cooking was being done one day every summer, and maybe again at Christmas?

An article from an unexpected source further proves that the plantation slave was once typecast as the quintessential barbecue cook. When Vogue reported from Galveston on a “Texas Plantation Party” in its January 1942 issue (back when it was acceptable to have a plantation-themed party at which the cooks, the help, and the entertainment were all black, and the guests all white (your Paula Deen references don’t count here), it was “Uncle Green” (pictured at the top of this column) who prepared and basted the meat over the earthen pit.

Tim Miller helped explain why Texans might have forgotten slaves’ influence in his book Barbecue: A History.

Of course, barbecue would have come to much of Texas the same way it came to most of the American South: through the influx of slave owners and their slaves, moving west across the continent. The rewriting of the story of Texas described above not only made Texas history, focusing on cowboys, a proper subject after the Civil War, but in the process also wrote blacks out of the state’s history entirely, leaving a question mark in terms of where barbecue came from.

By the time Robb Walsh wrote his award-winning article for the Houston Press “Barbecue in Black and White,” the black pitmaster stereotype was gone from Texas. Walsh asked, “How did it happen that we forgot blacks used to cook barbecue in Texas in the first place?” Walsh also recounts an admission from a famous white barbecue joint owner about Memphis’s barbecue roots. Charlie Vergos of the famous Rendezvous restaurant told Lolis Elie in his documentary Smokestack Lightning: A Day in the Life of Barbecue:

Brother, to be honest with you, [barbecue] don’t belong to the white folks, it belongs to the black folks. It’s their way of life, it was their way of cooking. They created it. They put it together. They made it. And we took it and we made more money out of it than they did. I hate to say it, but that’s a true story.

This admission isn’t something you often hear discussed when the history of Texas barbecue comes up. As I’ve written before, I have no doubts that the German and Czech meat markets were the womb where Central Texas–style was born. It’s a well-documented genre of post–Civil War barbecue preparation, but smoked beef on butcher paper isn’t the full story of Texas barbecue. Slaves were cooking barbecue here long before any butchers put it on a menu.

This post has been updated to correct the spelling of a name: It is Frederick Douglass Opie, not Fredrick.

- More About:

- Black BBQ