At fifty hotels across Austin, continental breakfast lines are bustling. Families wake up early to try to cram in enough Pop Tarts, muffins, cereal, and milk to hold them until the next day.

These are the recipients of vouchers from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which have given families temporary housing in hotels across Austin after their homes were destroyed by Hurricane Harvey. The first FEMA hotel vouchers were issued on August 30, five days after the disaster declaration was made, but they arrived at different times and dates for everyone—or, in some cases, not at all. Many people who’d been staying in temporary shelters received vouchers just before the centers closed, but others’ applications were still pending, or—even worse—denied.

According to FEMA, as of October 6, 852,744 households have applied for assistance. Only 308,862 applications have been approved, but FEMA couldn’t provide numbers on how many are still pending and how many were denied. People are denied FEMA aid for a wide number of reasons, and in some cases, it might seem, for no reason at all. Aid eligibility rests on being able to prove U.S. citizenship and residence at an address rendered unlivable. This might seem easy, but pitfalls abound: people who lived with roommates or family and might not be listed on a lease or a utility bill; people who lived with too many other applicants; people whose homes could be owned by incarcerated spouses or exes; exchange students, foreigners, and undocumented people who cannot offer proof of citizenship; people who lost their identification in the storm, or their landlord’s phone number. The list goes on.

Ironically, an application will be denied if the home is inaccessible to the inspector—for example, if it is because it is underwater or there are downed trees blocking the road in. “If the inspector can’t get in to review the condition of the property it will be denied because they cannot see it,” says Deanna Frazier, FEMA media relations manager for Hurricane Harvey. “People will need to go through the appeal process.” But many survivors of the storm aren’t aware of the appeal process. And even if they do try again, FEMA appeals can take up to ninety days.

When people apply for FEMA aid, they have to provide an alternate address to be contacted by mail, which presents another problem. “If we went out to check up on them and they weren’t there—maybe they moved since that time—that could trigger a denial,” Frazier says. “I know it may be a little onerous on the survivor, but we’re trying to be good stewards of the taxpayer dollars and make sure that people are who they say they are.”

And if an application is denied, FEMA will only communicate the reasons via paper letter, which they mail to the last address registered in their system. That could be a shelter that evacuees have already left, or the house ruined in the disaster. For a transitory population, this method can seem designed to fail.

Even for the people lucky enough to avoid the initial denial, vouchers were only a temporary fix. On Saturday, September 23, one of two recorded phone messages from FEMA was sent to every evacuee using vouchers in the hotels. One said: You are now eligible for an extended hotel voucher. The other: You are not eligible for an extended hotel voucher. One word made all of the difference. And on the recordings, the difference between “not” and “now” was almost indiscernible, leading to confusion and jammed phone lines. The wait to talk to a FEMA representative on the phone was up to seven hours. In the meantime, FEMA’s website went completely down.

The first wave of FEMA vouchers expired at 11 a.m. on Tuesday, September 26. Many were extended for fourteen days, but for those without further vouchers, the struggle deepened. Suddenly, they were left with no shelter, no money, and even less to eat. According to Frazier, on September 24, there were 69,185 individuals in 24,440 voucher rooms. Two days later, there were 59,195 individuals in 21,046 rooms. That meant almost ten thousand people had to make new arrangements.

What’s happening in Texas right now is a test case for the first wave of homelessness post-disaster. The end of September began the critical first-month juncture when every entity possible must act in order to seal the cracks that vulnerable people can fall right into.

These are some of their stories.

Belinda Salinas was working two jobs when Harvey hit. As a fry cook at Popeye’s, who was also training to be a manager at Wendy’s, she worked ten hours a day to keep her family in an efficiency apartment. Her wife, Kristi Perez, was pursuing her GED and caring for their sons Erik, 12, and Abram, 10.

Under mandatory evacuation orders, Salinas and Perez packed up and left their apartment in Victoria, which was filling with water. They stayed for three days in a shelter outside the city, in an area that didn’t sustain such massive flooding. Then, evacuated Victoria residents were bused to a Red Cross shelter in an Austin high school. They were there for almost a week before that shelter closed, and were then moved to the consolidated Austin megashelter—a huge warehouse room in an industrial park near the Austin airport. The Red Cross anticipated housing 2,000 evacuees from multiple closing shelters there, but only received around 600.

While the family was away from their apartment, they were evicted and all of their belongings were disposed of. Many renters across flooded regions have experienced evictions or buyouts, which is so common that Texas Rio Grande Legal Aid distributes fact sheets on renters’ legal rights in disasters, including lock-outs—or when landlords demand rent even after issuing eviction notices.

FEMA inspectors visited and declared the building—which they had been evicted from—habitable, and so claims from Salinas and her neighbors were denied. With the help of Texas Rio Grande Legal Aid, they will file suit. But that doesn’t solve housing right now.

When Red Cross closed the shelter, the family moved into a $54 per night room at the Motel 6 with a fourteen-day voucher. On September 25, the one-month anniversary of Harvey’s landfall, the family stood outside of the Motel 6 at dusk. Disoriented and surrounded by a tall pile of boxes, bags, and bedding, they looked at the highway, then back at all their stuff.

They had everything they owned at their sides but nowhere to go. A neighbor in the hotel had given them a phone number of a Red Cross volunteer, who passed them to several people willing to help. So on that Monday evening, they were waiting for a stranger, who had texted the couple, promising them beds in someone’s home. They’d fostered or put their pets up for adoption, except for Perez’s service dog that alerts her to the signs of epileptic seizure. They didn’t want to go to an unknown house, but they didn’t have another option. They’d never even stayed in a motel before that week, and only had about $40 between them.

The volunteer arrived, but the prospective host had declined, saying she didn’t want to house a lesbian couple. The volunteer took them to eat at Starseeds Diner near the University of Texas at Austin campus while she scrambled to make a new plan. Desperate, the volunteer blasted out Facebook messages to her friends. Who could take in four people and a dog that evening, for as long as possible? Could anyone pay for four more nights in a hotel? Several friends sent funds via Paypal, but the family still had no money for food and supplies.

By 8 p.m., the volunteer had located Mary, the mother of a friend, who agreed to house them. The family transitioned to the two spare rooms in Mary’s home, a bungalow with a big garden and three cats in South Austin. Overnight, the first volunteer collected several hundred dollars in donations so Salinas and Perez could repair their cell phones and buy medicine.

“If I hadn’t hooked up with those people, we would have been sleeping in my car,” Perez says. The family was able to enjoy their beds until Monday, October 2, when Mary had Airbnb guests booked—a six-day respite. After that, Kristi, Belinda, Abram, and Erik had no idea where they would sleep.

“It’s hard to live like this; we’ve never done this,” Perez says. “People that are poor—we’re trying to survive and make ends meet. We can’t afford a nice home or apartment, we have to settle for what we can. But we need something. If we go through another disaster I’m just going to sit it out, ride it out. Then I wouldn’t have been kicked out of the house I was in and we would have a place to live.”

Stephanie Hayden is the interim director of Public Health at the City of Austin. Hayden’s office assigned caseworkers to the people housed in Red Cross shelters, and set up a phone outreach process through which displaced people who contacted 311 for assistance would be referred to her office. Hayden’s caseworkers aimed to locate evacuees in the fifty FEMA hotels in Austin, ranging from the four-star Crowne Plaza to the dilapidated Motel 6 where Salinas and Perez landed. Yet only half of the hotels would share information about evacuees staying there.

Hayden’s office has the resources to send health workers and counselors out to meet evacuees where they are staying, help replace medicine and broken glasses, assist with FEMA appeals, and connect evacuees to other resources like Austin Disaster Relief Network, a nonprofit mobilizing churches. “We want to make sure every single person is taken care of and connected to the resources that they need,” Hayden says.

People in Red Cross shelters are on the radar of the organizations available to help them, but those who didn’t come to a shelter—instead going through a system of free Airbnbs offered after Harvey, or who couch surfed or slept in their vehicles—are often unaware of the lifelines available. Few of the people interviewed for this story were aware of the services offered by Hayden’s office.

Another hurdle, which has yet to be resolved, is affordable housing: the one thing evacuees need most.

“We already have an affordability crisis in Austin,” Hayden says. “No funds have been identified yet for affordable housing for people from the hurricane.” When hotel vouchers run out, families working with a City of Austin caseworker are given the numbers of other nonprofits. If those groups can’t assist, the family is directed to go to a homeless shelter. “We do not have transitional housing available for evacuees,” Hayden says.

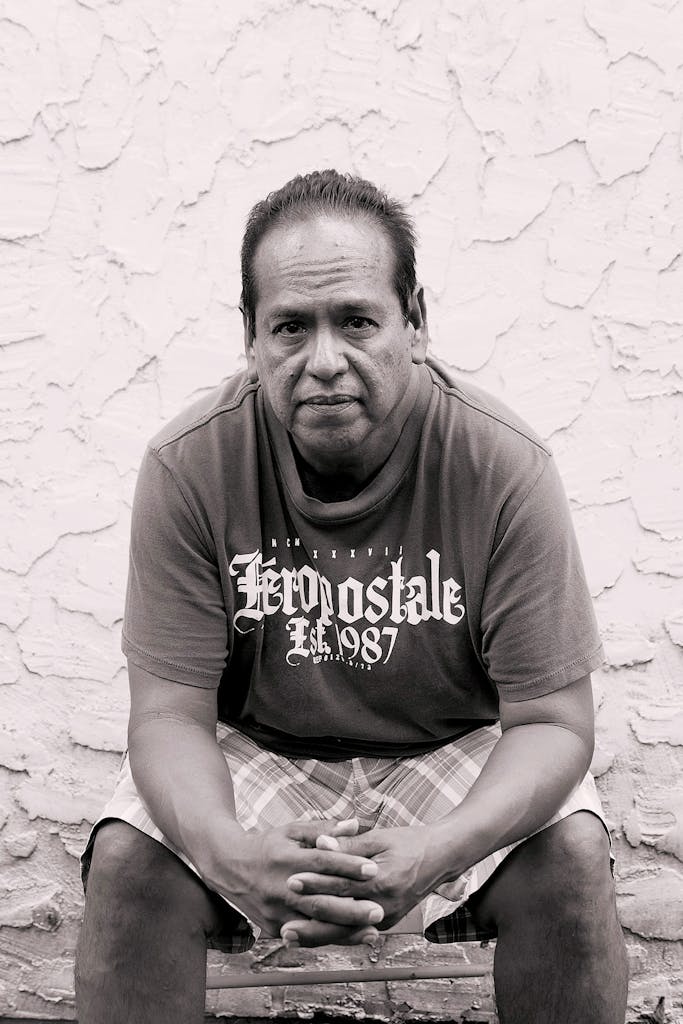

Soft-spoken electrician Larry Garcia, 51, was living in an RV park next to the shoreline in Palacios. His RV was almost paid off. Garcia, who was living on workman’s compensation following a serious injury, evacuated from his town of 4,682 people to Austin on August 23. The storm took out much of Palacios.

The week of September 18, he’d driven back to Palacios to meet the FEMA inspector, who declared his RV a total loss. He returned to Austin, where his truck broke down. He spent the Friday in the hotel praying that his voucher would be extended. It wasn’t.

When he got a FEMA representative on the line, they told him that his trailer was livable. He protested: FEMA and the insurance company both claimed it a total loss. But the representative wouldn’t budge. “I said, ‘What do you want?'” Garcia remembers. “‘Are you really telling me now I have to go and live underneath a bridge? You’re just going to throw all these families out in the street?'”

Before he received his now-expired voucher, Garcia stayed at the Delco Center, a Red Cross shelter in Austin, arriving before the storm hit. Six days later, he was ejected in the middle of the night from the Delco Center for distributing socks, underwear, bedding, and jackets.

“Children were shivering. They weren’t giving nobody clothes,” Garcia says. “The lady next to me was sleeping on a towel on the hard floor. So I asked people’s sizes and went to Walmart and came back with things for people.”

The police, according to Garcia, did not respond well. “They took me in the back and interrogated me for maybe two hours,” he says. “They said I should have donated them to the Red Cross so they could distribute it. I told them I haven’t had a traffic ticket in thirty years. I’m not doing anything wrong. I begged them if I could stay to the morning, but they said, ‘No, Red Cross wants you gone.’ So I was out there in my truck at night, I didn’t even know where I was.” Several witnesses, both Red Cross volunteers and shelter residents, confirmed Garcia’s account.

“FEMA is putting me out, and Red Cross put me out,” Garcia says. “Now I’m just out.”

Garcia is planning to return to Palacios when he gets the insurance settlement for his trailer. It might take a month or more, during which he’s not sure where he can go. When the check comes, he will buy another RV on the shoreline—and move it to higher ground when the next storm is whipping up in the Gulf.

Then there are the evacuees no one sees: undocumented families.

On its Hurricane Harvey website page, FEMA addressed common concerns for undocumented families: “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) have stated that it is not conducting immigration enforcement at relief sites such as shelters or food banks. ”

Still, to enter the parking lot of the Delco Center shelter in Austin, you had to stop before a bevy of police cars. An officer rolled would roll down the window of a squad car and ask you to state your reason for entering. ICE and FEMA are sibling agencies under the Department of Homeland Security, so the staging had the potential to pose an intimidating situation for undocumented families.

Undocumented people aren’t eligible to apply for FEMA; one of the first qualifying questions is U.S. citizenship. If minor children are citizens with Social Security numbers, they may be able to apply, but that is a complex endeavor, especially with a language barrier. Alberto, Isabel, and Isabel’s sister, along with six children, arrived at the Delco Center from Baytown and stayed for four nights. During that time, they largely did not have access to Spanish interpreters, and Isabel was unaware that diapers were available for her infant. Circle of Health International, a nonprofit that helps mothers in disasters, came with a Spanish-speaking staff person and diapers and wipes for her.

The last time they were seen by volunteers, the family was packed back into the van without rear seats. The floor was covered foot-deep with clothing, bags, and blankets. Alberto explained that the whole family would sleep there at night, stretched across the bed of the van, with the smallest children at the head and foot.

Jack and Julie Russell*, a couple from Beaumont, arrived in Austin with their seven-month-old, Jack, Jr.

With the support of an African-American grassroots community group called Counterbalance ATX, the family received clothing, diapers, food, and their first places to sleep. They moved from home to home, arriving at a new location every few days. They were weary. After contacting another community group, they ended up in the spare bedroom of a family they’d never met. Meg and Damon Poeter, their hosts, have four kids—including a newborn baby—in Round Rock. The Poeters agreed to host the Russell family until they found stability.

Meg is a Katrina survivor determined to use her disaster know-how to assist her guests, and wanted to push every relief agency to get the family into an apartment. She spent days on the phone with FEMA. Julie, a Certified Medical Assistant, rushed to get the first job she could; she was hired as a security guard. Jack looked for construction work.

Facing the inevitable need for a chunk of cash to put down on an apartment, and knowing that extended cohabitation would put a strain on the evacuee family, Meg and Damon asked their family in Louisiana to fundraise for Julie and Jack. “I’ll even take out a high interest loan if I have to,” Meg says.

On Craigslist, the Russells found a rare furnished apartment for $650 per month in West Campus. Their application was accepted, which was a coup given their low income and credit issues. Meg fundraised the deposit, and they were about wire it by Western Union, expecting the keys to be delivered by FedEx.

They were so close that Julie and Meg pitched the need to Catholic Charities, which was offering some relief, for the last boost of funds. Three days later, Catholic Charities called back and agreed to provide the first month’s rent.

Meg’s friend Amy Hayes, a realtor volunteering to help evacuees find low-income and Section 8 apartments, was skeptical. She asked the Russells to hold off on going through with the deal, then searched the tax records and the Multiple Listing Service, a database of home listings. She discovered that this “landlord” had downloaded photos from other rental sites and was orchestrating an elaborate scam from Mississippi. The apartment was owned by someone else and listed for $1,400.

Erica Danbury and her baby boy, Jojo*, were camping in someone else’s FEMA voucher room, hoping their own application would move from “pending” to “approved.”

A young woman from Vidor, Danbury arrived in Austin in a 1991 Buick station wagon with a truck camper upside down on top, loaded with cardboard boxes and extra car tires strapped down with rope. She brought her neighbors and their two children, whose truck had taken on floodwater, with her. Danbury came to Austin because she remembered traveling to the capital as a child.

The group didn’t go to the Red Cross shelter, but they didn’t have a voucher yet either, so they slept in the car. Danbury worried that abuse could take place at the shelter, and that because of the trauma of losing her home, her mental state was too fragile to be around hundreds of people. Instead, she messaged some Hurricane Harvey relief Facebook groups asking for a place to stay.

Then her neighbor’s FEMA aid and hotel voucher were approved. But her voucher was still pending. “We lived so close to each other. It doesn’t make sense,” she says. “I lived in a stilt house next to the reservoir. When they opened the dam, my house went completely underwater.” Her frustration made her voice tremble. They all moved into a Holiday Inn double queen room. She slept in the bed with three children, and her neighbors slept in the other bed.

Danbury, who lost her phone in the evacuation, doesn’t know how to contact her landlord—or if he’s even still in the area. Unable to produce a lease or a utility bill, or pictures of her furnishings, it’s unlikely that she will be approved for any aid. A woman she met at the hotel gave her money for a new phone and to pay her phone bill. Besides her foods stamps, that’s the only money Danbury has had since leaving.

On September 23, her friends got the “not eligible for an extension” voice recording from FEMA, and Danbury began to sob. “I just don’t even know what I am going to do. I have nowhere to go. I have nobody.” As she nursed Jojo, she began texting the few phone numbers she had to try to find the next place.

With a lead from an acquaintance on September 28, Danbury contacted the owner of a bed and breakfast in San Marcos, a scenic river town south of Austin that hasn’t had any business since the hurricane. Its primary clientele hails from Houston, and the B&B’s business has been limited since Harvey. The owner had offered to host a few evacuee families temporarily, and invited Danbury to come meet her. Danbury and Jojo moved in later that night.

Their precarious position will resume again when tourists seeking a respite from the city book the B&B’s rooms. But before the travelers start to frequent the bed and breakfast again, Danbury can imagine, for a few more days, that they are in a safe home.

Abe Louise Young is a writer and educator in Austin, and the co-director of Prizer Arts & Letters.