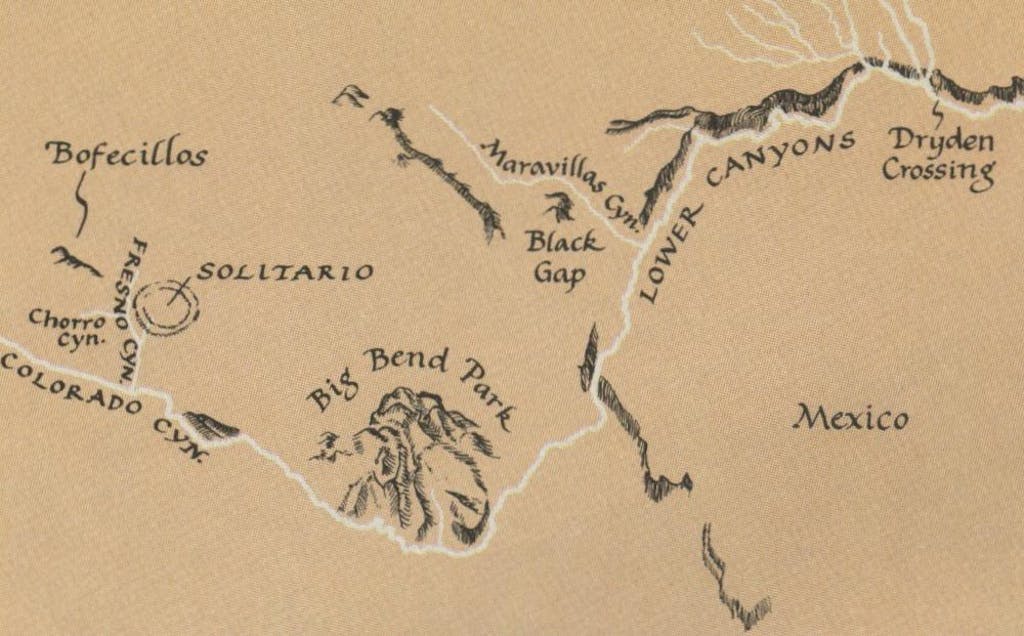

Those who have seen the Big Bend country know it as the most remote, majestically beautiful section of the Texas borderlands. Since 1944, the federal government has preserved the central portion as Big Bend National Park. This sanctuary from the pressures of civilization has become so popular that 450,000 people visited it last year—up from 175,000 in 1970. Much less well known, however, are four other areas equally deserving of preservation which lie nearby: the Solitario, Fresno Creek, Colorado Canyon, and the Lower Canyons of the Rio Grande.

The first three are all located on land west of the park owned by the Diamond A Cattle Company’s Big Bend Ranch, a sprawling expanse of more than 300,000 acres. Its natural springs continue to flow—unlike so many others in West Texas—because its former owners, Edwin and Manny Fowlkes, built hundreds of miles of pipelines from the springs to the mesa grasslands instead of depleting the aquifer with wells. The ranch is the last large unspoiled part of the Big Bend country remaining in private hands. At Land Commissioner Bob Armstrong’s instigation, the Texas Legislature is currently considering a proposal to purchase it from oil executive Robert Anderson.

The fourth area lies east of the national park, downstream between Boquillas and Langtry. The Lower Canyons of the Rio Grande constitute one of the three wildest rivers left in the United States, comparable only to the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in Arizona and Hell’s Canyon of the Snake River in Idaho. The fate of the Lower Canyons is now in the hands of the federal government, which could either inundate them behind a series of dams, or protect them permanently as a wilderness preserve, depending on which agency wins the bureaucratic battle.

Like so much of the Big Bend country, the Lower Canyons and the Big Bend Ranch have a value beyond measurement. They are the last surviving huge wild part of Texas. To explore them is to touch for a moment the frontier experience shared, in different landscapes and under different climates, by those who subdued the Hill Country, the Staked Plains, and all the other stern resisting wilderness a century and more ago. The utter solitude, broken by the sound of birds and insects only, reconstructs the mood of limitless possibility and vague foreboding that faced everyone who pushed the frontier westward. To experience it is to bridge the gulf that separates us from those ancestral settlers, letting us learn physically what we can never fully learn from books and legends.

SOLITARIO

A Separate Place

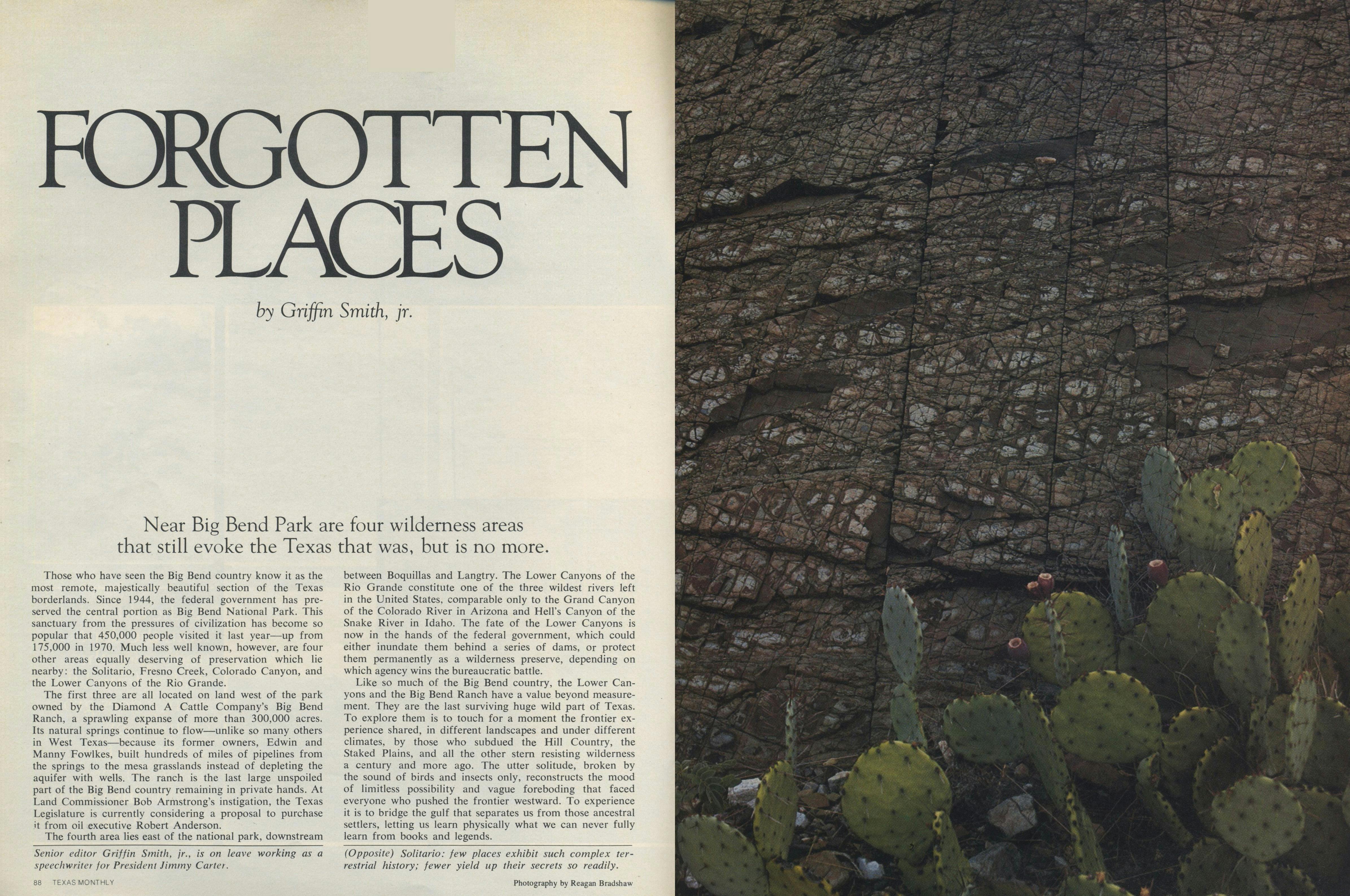

Austere, aloof, the vast circular geologic uplift called the Solitario lies in splendid isolation twelve miles due north of Lajitas. From the air a casual observer might mistake it for the crater of a meteorite or the collapsed cone of an ancient volcano, so startling is its symmetry. From the ground its jagged limestone rim roils up like a wave of stony whitecaps above the turbulent surface of the Big Bend country.

There is—has always been, since the days of the Spaniards and before—a sense of separateness about the Solitario. One ascends to the brink of this elevated, sloping bowl, eight miles across and sealed inside almost impenetrable walls, expecting that some kind of paradise must surely lie within: if not a lost kingdom, then at least some well-watered, fertile respite from the surrounding countryside. But the allure of Xanadu is an illusion. Unlike the Big Bend’s other hidden place, the green and hospitable Chisos Basin, the interior of the Solitario is arid and forbidding. It is a respite from nothing; instead, it distills into itself all the harsh wild beauty of the uncompromising Chihuahuan Desert.

This portion of the Big Bend Ranch is above all else a remarkable geologic library. Few places in Texas exhibit such a complex terrestrial history, and still fewer yield up their secrets so readily. To the practiced eye the story is plain: the tortuously folded ancient Paleozoic rocks lying exposed in the Solitario’s center; the limestone sifted down by Cretaceous seas and then thrust into a great protective escarpment by the still-unknown forces that uplifted the Solitario dome some fifty million years ago; the lava flows and ash falls of Tertiary time; and the effects of erosion that began, millennia past, when the ancestral Rio Grande began to carve a steady downward course, draining runoff out of the Solitario through four narrow and ever-deepening canyons.

These canyons, locally known as Shutups, provide the only natural passages into the Solitario. (In the north, a primitive road now vaults the rim.) The way is difficult: gradients sometimes reach 400 feet per mile, and the canyon floors are hemmed by walls of limestone and red conglomerate towering as much as 750 feet. In the Lower (or southern) Shutup—the largest, most isolated, and most breathtakingly beautiful of the four—smooth-sided tinajas cup deep pools of jade-green water, obstructions or diversions depending upon one’s mood. Except in the driest seasons, a shallow flowing stream two or three feet wide meanders over gravel bars between these pools, disappearing and reemerging as if by whim. But the calm, steep-shadowed serenity of the Shutups is deceiving: floods accompanying late summer thunderstorms transform them into places of mortal peril, roaring gorges where giant boulders are tumbled about by the current’s overwhelming force.

So rugged is the interior of the Solitario that a good day’s expedition seldom covers more than fifteen miles, and then only with the aid of a sturdy four-wheel-drive vehicle. To the north, shale lowlands and low sandstone ridges predominate; to the south, volcanic tuff. Characteristic desert grasses, much thinned by grazing, survive in scattered clumps. The black and green chert of the Maravillas Formation and the distinctive white rocks of the Caballos Novaculite cap the high ridges rising from the basin floor, contrasting sharply with dark igneous mountains like Needle Peak. Man-made landmarks are few: some scattered tanks, the pump house at Tres Papalotes, and the remote, forgotten Burnt Camp. Permanent surface water is altogether lacking. This is the rawest country known to Texas; to enter the Solitario is to take leave of everything but elemental nature.

Its plant life is, with a few notable exceptions, typical of the Big Bend. Geologic diversity, however, allows species that ordinarily grow in widely separated sites to flourish in close proximity to one another. The rim hosts ocotillo, agave, sotol, and desert shrubs like silver-leaf; the interior basin, creosote, mesquite, catclaw acacia; while in the relatively more hospitable Shutups, ash, walnut, and Mexican buckeye struggle for water in the dry months and cling for life against the periodic torrents. These canyon plants and others like the Havard plum are relics of an earlier age when the climate of the Solitario was cooler and wetter than it is today; they endure in their isolated canyons only because the high cliffs provide shade and shield them from the Solitario’s brutal evaporation rate (at ninety inches a year, the highest in the state).

The preeminent botanical treasure of the Solitario is the colony of some 45 Hinckley oaks clustered together on a low limestone ridge. Except for another small colony near the abandoned mining town of Shafter, these tiny, two-foot-high shrubs are the only known examples of their kind.

The Solitario’s zoology, like its botany, is noteworthy less for any inherent uniqueness than for the way it brings together within a single small area a great variety of normally scattered life forms. One finds familiar vertebrates like kangaroo rats, checkered whiptail lizards, jackrabbits, cottontails, and mockingbirds. More than 100 species of birds have been identified within the Solitario, among them two rare elf owls seen nesting near Tres Papalotes. The Big Bend gecko, a rare lizard, has been found near the Lefthand Shutup, and leaf-chinned bats are known. The predators of this 40,000-acre basin are distinctly different from those that prowl the adjacent countryside. In most of West Texas, man’s gradual extermination of large carnivores has left the field to smaller animals like raccoons, skunks, and foxes. In the Solitario the situation is reversed. Cougars and coyotes rule, the rest are scarce or absent. Attracted by the seclusion of this strange wild place, the cougar has kept its rank in the natural order of things—for how much longer, no one can say.

Waking to a coyote’s cry under a canopy of stars, one realizes how far from humankind the Solitario is. From all evidence it has always been so. Nineteen archaeological sites have been identified within its boundaries, some dating back perhaps 12,000 years; but their contents—scattered lithic tools, fire-cracked rocks, manos, metates, and soot-blackened shelter ceilings—suggest that prehistoric man paid only brief visits in search of food and weapons before returning to the more congenial regions of Fresno and the Bofecillos: a temporary sojourner, nothing more. Its Spanish history is nonexistent. Even the American ranchers, who did not arrive in numbers until the twentieth century, set up their own residences far away. The occasional overnight campsite of the cowhand is man’s only recurring modern presence. So far as we know, in 12,000 years not one permanent human habitation has ever been constructed in the Solitario.

No lost kingdoms here, nothing of the kind was ever seen in this negative oasis. But those who know it best insist it is enchanted, will tell you of strange things that happen on moonless nights, will tell you of the three men who sat in the half-light of a campfire at Tres Papalotes when a fourth came up and stood by them, all silent, before fading into the shadows. In the Solitario, they will tell you, you always know who is there; and there were just three men that night, not four. Who then was the fourth?

Such stories are, one understands, a commonplace of cowboy folklore: the silent stranger who emerges from the dark to share the fire and melts away unseen, an apparition. But somehow they seem more believable out here, in this prickly, hollowed-out cup of earth, inside these fierce excluding walls, where one small campfire crackles vainly against the universal dark. Ghosts, if they be, would surely come.

FRESNO CREEK

Desert Cloister

The search for water is the one abiding constant of human life in Trans-Pecos Texas. It has dictated the routes of travelers, the sites of towns, and the likelihood of wresting a living from an obstinate land. Because the oases are so few they have been treasured immemorially. It seems inconceivable that any of them, once discovered, could ever be forgotten.

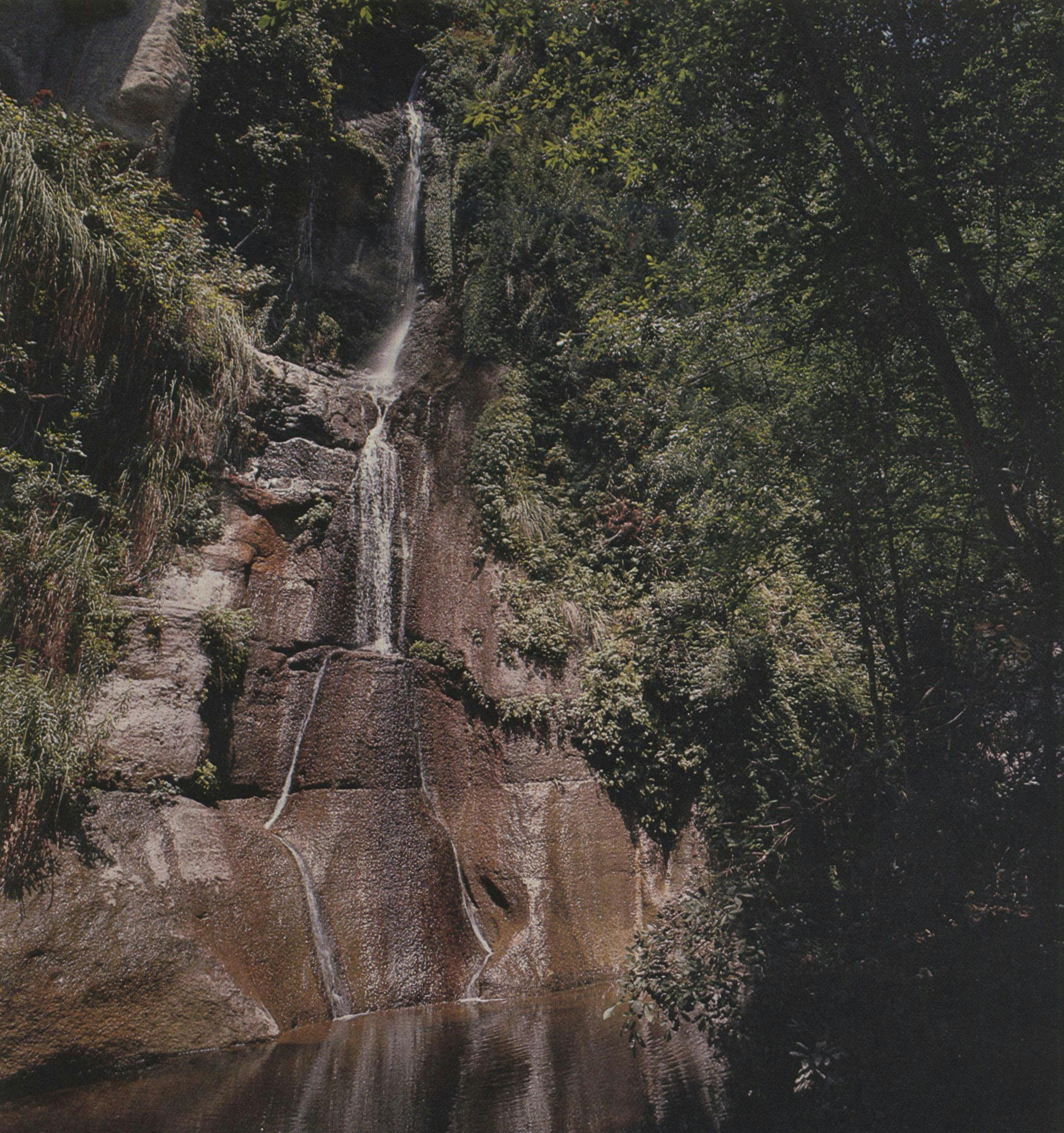

Yet that has been the fate of the nameless perennial stream which flows through a side canyon known as Chorro in the uplands north of Redford. Fed by springs bubbling out of basalt porphyry in the eastern Bofecillos Mountains, it drops through two cascades 100 feet and 30 feet in height before coasting lazily along a reed-choked bed toward Fresno Canyon and the Rio Grande. The stream must have been known to prehistoric man, and it was certainly known to early settler C. H. Madrid, who came there in the 1870s and eventually built a ranch house on a fertile terrace near its banks. But in time the Madrids moved to Redford, taking the memory of Chorro Canyon with them. When a topographic survey team “discovered” the stream and waterfalls in 1970, the news came as a surprise to all but the Madrid family and a few hands on the Big Bend Ranch.

The larger waterfall, christened Upper Madrid Falls, offers a miniature forest of lush vegetation that may be the closest thing to Eden West Texas will ever know. Cottonwood, willow, oak, and ash fill the narrow canyon, cloaking the splash pool in almost constant shadow. The stream itself slides in a diamond-shaped pattern down a rock face nicknamed “the pedestal,” passing rare columbine, wild rye, and maidenhair along the way. Replenished by underwater springs, it flows through a thicket of crumbling logs and grapevines to the lesser lower falls. Animal life that could not last more than hours in the adjacent desert survives trapped, if that is the word, amid the cool and damp perpetual green. The secretive Madrean cliff frog, whose cry is heard only when the humidity meets its satisfaction, is found here; so, too, are the canyon treefrog and the rare, relictual Trans-Pecos copperhead.

This fragile ecological island continues to exist only because the Chorro watershed above the falls is small enough to escape the tumultuous flash floods that regularly rip the vegetation from other Big Bend canyons, including Fresno Canyon itself, into which Chorro Canyon empties.

Despite the floods, water is Fresno Canyon’s special wealth. This mile-wide valley separates the Solitario from the Bofecillos Mountains, carrying runoff from each into the Rio Grande. Fresno Canyon’s two sides are dramatically different, not only in their biology but in their geology as well. The eastern, or Solitario, slope consists of steeply dipping, pale Cretaceous limestone. Devoid of natural surface water, it supports an environment indistinguishable from the Chihuahuan Desert norm. The western, or Bofecillos, slope is built of alternating hard and soft volcanic rocks; ground water trapped between the layers emerges to dissect the dark cliffs with mesic canyons like Chorro. Other springs, always from the west, form tiny ponds within Fresno Canyon proper, attracting migratory birds, butterflies, and a host of water-loving fauna. Between them the canyon bed looks dry; but in actuality water seeps slowly along through moist gravel a foot or two beneath the surface, readily available with a shovel and a little effort.

The botany and zoology of Fresno Canyon each contain elements of the unexpected. Six varieties of rare plants have been discovered, four of them along Fresno Creek itself. Zone-tailed hawks, golden eagles, and the endangered Mexican duck have been observed. The area is rich in bats whose normal range lies much farther south in Mexico; western mastiff bats and big free-tailed bats both frequent the vicinity, indicating that colonies may be established nearby. Other species are believed to occur—the spotted bat, which, if bats can be considered beautiful, is considered the most beautiful of bats; and the Mexican long-tongued bat, which feeds upon the nectar of blooming century plants. Because Fresno Canyon drains into the Rio Grande, it has provided a historic passageway for bears and mountain lions wandering north from Mexico.

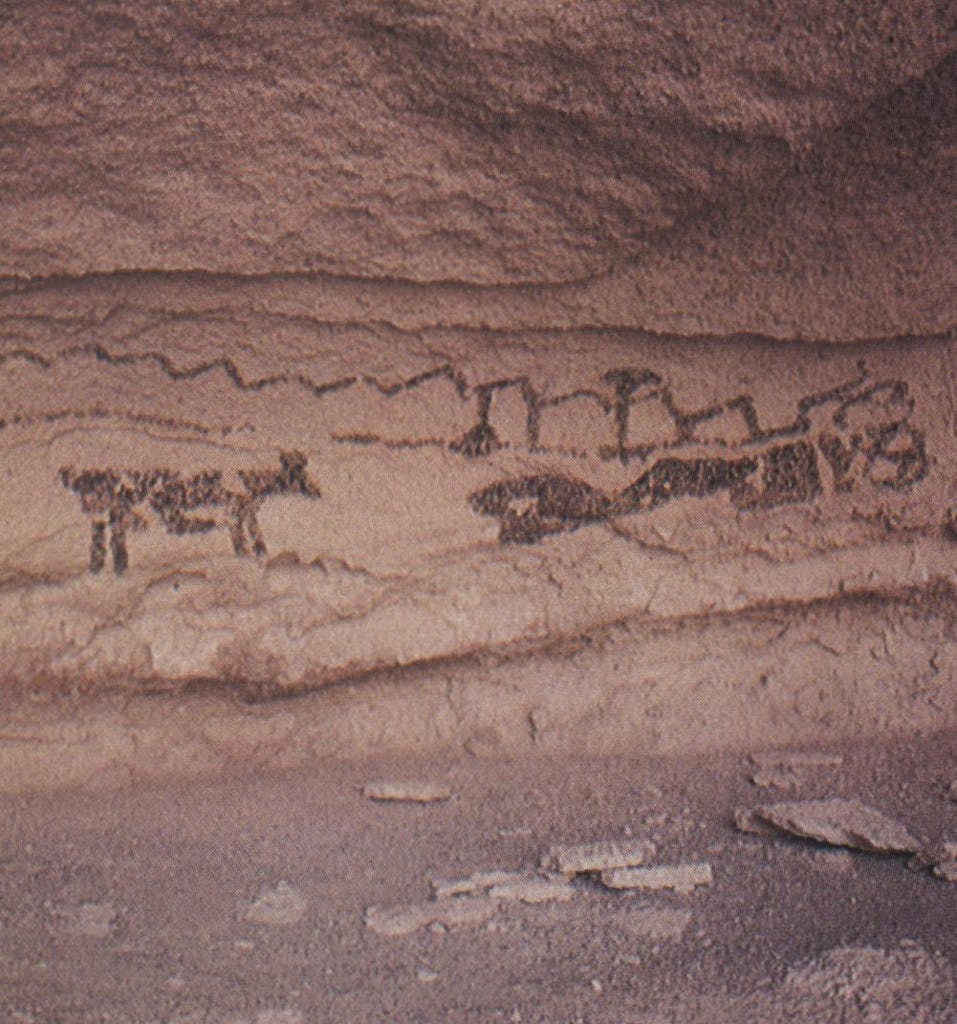

To primitive man, the watered canyon must have seemed a far more attractive home than the arid Solitario. That is not, however, saying much: the nearly three dozen archaeological sites now known suggest a long period of bare subsistence, characterized by foraging and small-game hunting under conditions that made the search for food an almost full-time occupation. There is no evidence that the prehistoric inhabitants of Fresno practiced any sort of agriculture or raised domestic animals. However, they left behind a small collection of simple pictographs. One site, whose smoke-blackened roof consists of a remarkable grooved slab of limestone thrust down as the Solitario was uplifted fifty million years ago, has been decorated with colored handprints. Another, which depicts men on horseback, indicates that Fresno Canyon was inhabited at least until Europeans arrived in the region.

European influence was long confined to the Rio Grande; the white man came late to Fresno Canyon itself. La Junta, now Presidio, was well established when Antonio de Espejo passed through in 1582; and a place called Tapalolmes, near modern-day Redford, was visited by Rabago y Teran in 1747. But Fresno remained untouched. North-south travel, such as there was, flowed for centuries along Alamito Creek, thirty miles northwest of Fresno and nearer to La Junta. This was the route chosen by Espejo on his journey from Santa Fe to the Rio Grande; later it flourished as the Chihuahua Trail, a passageway for American goods before the Civil War, and for American cattle after.

Fresno basked in silence until the twentieth century, when a rugged road from Marfa to Lajitas was cut through to give access for the Terlingua mining district. Mule pack trains (immortalized in the photographs of W. D. Smithers) dodged potholes, forded streams, and circumvented rock slides to make the journey in three days. In 1916, when Pancho Villa and his men hid out in Alamito Creek, U.S. Cavalry reinforcements used the primitive Fresno Canyon “highway” to station themselves at Lajitas against his depredations. Along the route they saw the things we see today: to their right, mountains concealing springs, cool water, and grassy shade; to their left, the Solitario’s awesome toothed rim and its three colossal false apertures known as Los Portales.

Beside that road, rancher J. F. Crawford built a home in 1918. The spot he chose was sheltered from north winds by the serrated ridge of Rincon Mountain; it was near a spring, of course. Behind a neat stone wall breached by a wooden gate, he laid down hardwood floors and placed a mantel on his fireplace; outside the living room he built a terraced formal garden with an ornamental pool, and in the back, he placed a citrus orchard. In time the house was bought by Harry Smith, who, like Crawford, raised angora goats. Smith stayed until the forties, defying climate, predators, and isolation, then sold his land and left.

The Marfa-Lajitas road, now given back to private hands, lies abandoned and impassable through much of Fresno Canyon. The Smith House, as it now is called, is a scene of chilling melancholy. The white man came late to this unconquerable country, and he did not—could not—stay; even the water could not make it his. Nothing is left but the whitewashed shell; the hardwood floors are gone, the fireplace stripped, the windows carried away, the roof in ruins. Thorn-bushes clog the decorative pool, while in the orchard one last gnarled orange tree inexplicably survives. Over the door a horseshoe rusts.

COLORADO CANYON

Wilderness Corridor

Colorado Canyon is the first, and shortest, of the Big Bend’s monumental canyons. Its entrance 28 miles southeast of Presidio brings to a close the broadly majestic, even extravagant, valley through which the river has passed for most of its length below El Paso. Beginning at Colorado Canyon the Rio Grande struggles to find a path to the sea.

Eons ago, the volcanic rock at its entrance was a natural dam holding back a vast lake within the Presidio and Redford Bolsons. Sediments carried by rainfall runoff in the ancestral Rio Conchos and by snowmelt in the watershed of the ancestral Rio Grande gradually filled the basin until the dam was breached. With excruciating slowness, the waters began to etch a downstream path, excavating canyons that have steadily deepened over time and surrounded the river with a scenic badlands of eroding tributaries.

The barrier broken by the river proved more difficult for man to overcome. Colorado Canyon, together with a formidable dome of rhyolite porphyry two miles downstream known as Big Hill, impeded human traffic across this region from prehistoric times until a road was blasted through in 1961. Archaeological evidence shows that the settlements of Indians who practiced agriculture and manufactured pottery throughout much of the American Southwest cease abruptly near Redford; not a single ceramic sherd has been discovered at Colorado Canyon or beyond. Similarly, the area’s lithic artifacts do not correspond to types associated with the Big Bend, the Davis Mountains, or any downstream culture, prompting archaeologists to speculate that whatever primitive peoples lived here were an isolated society confined to the Colorado Canyon-Fresno Canyon vicinity.

Presidio is of course rich in both Spanish and nineteenth-century American history; but its commerce flowed along a north-south line through the interior, avoiding the river and Colorado Canyon. By following a passable route through Alamito Creek, the Chihuahua Trail linked Presidio far more closely with northern Mexico and the American Midwest than with the rest of Texas. Efforts to find a safe passage from San Antonio through Presidio to El Paso came to grief in the Hays-Highsmith expedition of 1848 and the Whiting expedition of 1849. Not until after the Civil War was the connection made, and even then it crossed overland, far from the river.

The spectacular entrance to Colorado Canyon was viewed as the gateway to an unknown region as late as 1852, when Major William Emory’s scientific reconnaissance party passed through. His was the first serious attempt to chart the hidden reaches of the river, if one discounts the ludicrous Love expedition of 1850, which tried to reach El Paso from Rio Grande City in fifty-foot flat-bottomed boats, and the saner Smith expedition, which managed to navigate upstream to a point eighty miles above the confluence of the Pecos. The work begun by Emory was not resumed until 1899, when geologist Robert Hill, with far greater expertise, mapped the entire river system from Presidio to Langtry. In the interim and until quite recent times, man was a stranger to the swirling water and the sunsets refracted beneath the craggy walls; Colorado Canyon slept the deep primeval sleep of wilderness unobserved.

Today it is easily negotiable by canoe or kayak, especially during the spring or fall when water levels are most likely to be favorable. Access is almost effortless; Camino del Rio links the two points with a ten-minute drive, and the land (still private) slopes gently to the river. Between these points the road veers out of sight behind a ridge, allowing the lucky canoeist total solitude for the duration of his run. Few wild rivers anywhere are so well adapted to satisfy an intruder’s every wish.

At normal water the trip takes half a day. Enough rapids exist to keep the adventure lively, but the canoeist can still find time to admire the geologic drama unfolding around him. Through immense faulted blocks of volcanic lava, tuffs, and ash the Rio Grande cuts, rolling past massive columnar jointed cliffs of weathered orange ignimbrite. In the deepest part of the canyon, the walls rise 800 feet above the water’s edge.

A narrow, steep side canyon enters from the left. This is Closed Canyon, a tributary carrying outwash from the Bofecillos Mountains. No more than a few yards wide in several places, it provides valuable shade during the heat of the day. The broad-tailed hummingbird has been seen nesting here, as has the prairie falcon; and the rare perennial Machaeranthera gypsophila displays its showy white-and-yellow flowers after a drenching rain.

The slender green band of vegetation along the river is dominated by plants foreign to the botany of the Chihuahuan Desert: Bermuda grass and salt cedar, both native to India; carrizo, an Asian grass; and South American tree tobacco, beloved by the six species of hummingbirds known to visit here. But the sandy banks of Colorado Canyon also play host to such familiar domestic plants as mesquite, seep-willow, canyon grape, sunflower, and poison ivy.

With more justification than canoeists have, bats and birds use the river as a corridor through otherwise inhospitable terrain. Multitudes of migratory waterfowl pay annual visits; others arrive and depart with unpredictable irregularity. Birders’ records are replete with more than 150 different species, and twice that many are thought to put in an appearance during any given year.

As the river emerges into lowlands between the canyon and Big Hill, startled canoeists have occasionally encountered equally startled bears, who turn tail and head back to the sanctuary of the Mexican mountains. Much more common, however, are the mysterious Mexican beavers, who do not build dams or lodges as proper bourgeois beavers do, but who nevertheless wreak havoc with their destructive gnawing of valuable shade trees. Muskrats are gradually returning to their former range along this portion of the river; several have been sighted upstream from Lajitas, and they may already have reestablished themselves as far west as Big Hill. Three rare snakes—the Texas lyre snake, the Trans-Pecos rat snake, and the gray-banded kingsnake—are among the many species known to inhabit Big Hill.

Construction of Camino del Rio, which made these canoe trips feasible, has paradoxically set in motion forces that could destroy Colorado Canyon’s fragile ecology. Commercial animal dealers from as far away as California now flock to the highway to capture and eventually sell rare specimens of wildlife, particularly the gray-banded kingsnake, which fetches more than $100 in the pet trade. Fishermen have already introduced one foreign species to the river, the barred tiger salamander; and they have been known to smash the dry mud nests of cliff swallows and use the nestlings as bait.

The greatest threat to Colorado Canyon’s survival comes, however, from an altogether different source: the river itself. Even in Spanish days the Rio Grande above La Junta occasionally ran dry; modern dams have simply made an intermittent condition almost permanent. For decades, the Rio Conchos has supplied the flow that kept the “Rio Grande” below Presidio alive. The riparian existence of Colorado Canyon depends largely on the rains of the Sierra Madre Occidental, transported by the Conchos across the arid reaches of northern Mexico. But dams built for irrigation in the mountains southwest of Chihuahua have increasingly begun to stanch that flow. Although a minimum supply of water is presently guaranteed by international treaty, the desperate agricultural needs of Mexico’s burgeoning population may soon require all the water the Conchos can provide. Treaties have been known to yield to less. If the alternative is hunger, Colorado Canyon may be fated to become, before the end of this century, a dry arroyo evidencing the fitfulness of man’s rapport with nature.

LOWER CANYONS

Time and the River

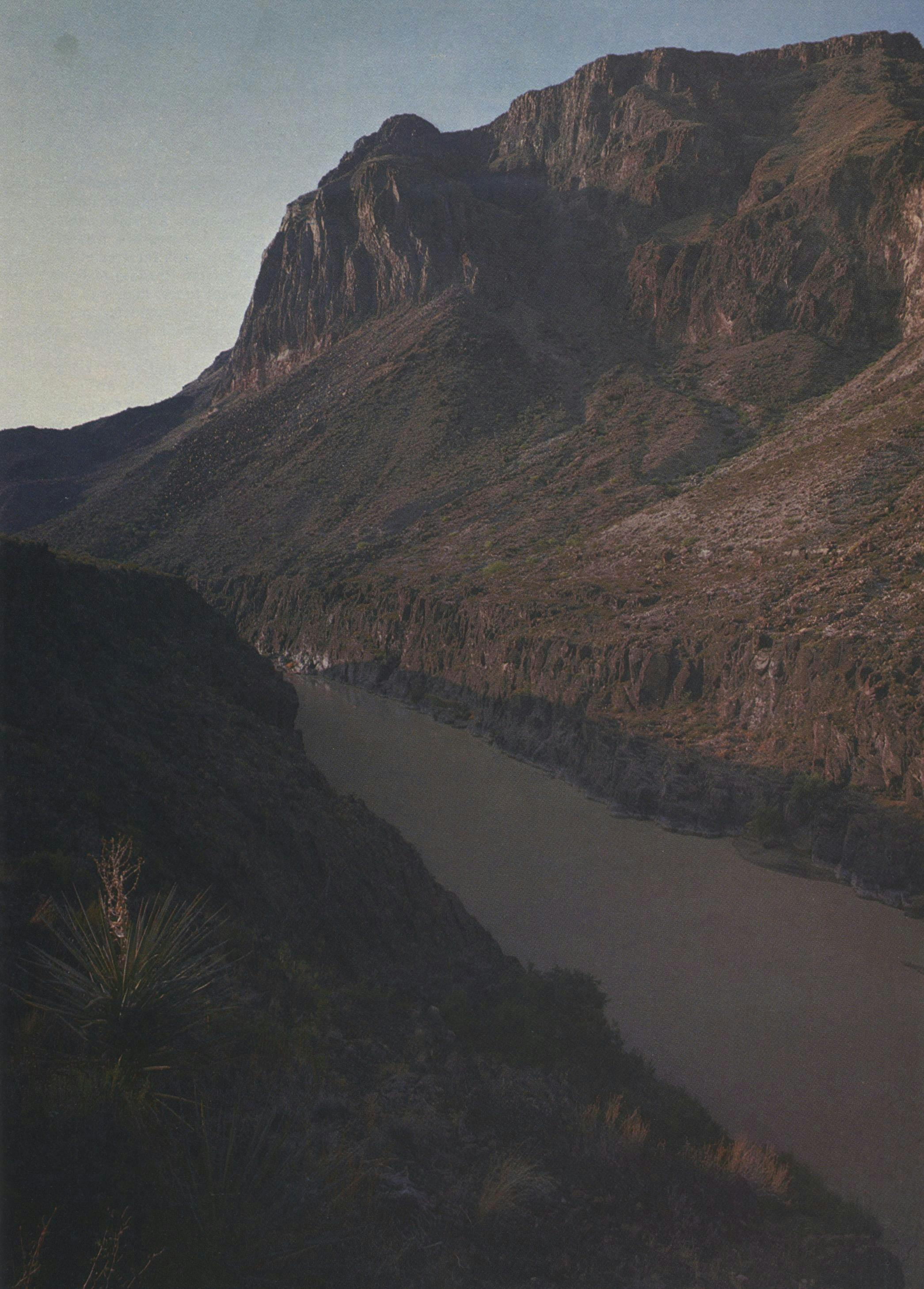

Of all the wild places that remain in Texas, none bears more eloquent witness to the supremacy of nature than the Lower Canyons of the Rio Grande. Prehistoric man struck with them a cautious bargain for sanctuary and sustenance of life. The impatient invading Spaniards, seeking passage through the despoblado, put misplaced trust in fragmentary maps and struggled in bewilderment against them for two centuries. Normally self-confident American explorers recoiled with awed respect from the daunting mystery of their cliffs and rapids. Not until 1899 were the canyons fully charted by a scientific expedition; and before 1970, they remained an unknown land to botanists, zoologists, and archaeologists. Even today, this 95-mile ribbon oasis downstream from Big Bend National Park has scarcely changed from the days of the Apaches: its green spring-fed water, its Grecian blue sky, its pale orange bluffs, and the silhouette of a hawk soaring above a dry side canyon define with timeless simplicity the state’s most exhilarating wilderness experience.

As the Spaniards and the early Americans found to their dismay, the Lower Canyons are impassable both by land and by any vessel larger than a canoe. A float trip, including portages, requires five to eight days. Once a party has embarked, there is no way out for the duration of the journey. Fewer than a thousand people have ever made the trip.

Before 1973, most of the biological history of the Lower Canyons was conjectural, derived from observations at Black Gap Wildlife Management Area adjacent to the park. Black Gap is still the best place to begin an expedition. Where the Rio Grande meets a tributary called Maravillas, a stony outwash forces it into a channel no wider than a creek; a pebble pitched across eight or ten feet of water will land in Mexico—another sovereignty unmarked by border posts or fences. Lines on maps may show the river as a boundary, but nowhere in these canyons will the canoeist feel any sense of passing along the frontiers of two nations. The river binds together; it does not separate.

Maravillas Canyon reflects the many-layered history of the Big Bend country. Here, in 1852, T. W. Chandler and Duff Green finally abandoned their attempt to survey the rugged boundary from Presidio to Fort Duncan and marched their men, bleeding and discouraged, across northern Mexico to Santa Rosa. Here, for weeks in 1893, Mexican bandits filtered across the river to rustle more than a thousand head of cattle from newly arrived ranchers who lived nearby—including, perhaps, some from the forgotten cowman whose burned adobe house stands now on a promontory among the campsites at Black Gap. Tonight at dusk under a graying sky two old Californians sit in folding chairs outside their curtained camper. A radio stands on a small ladder beside them. It plays rock: not their music, but in the Big Bend, where radio stations are scarce, they are not invited to choose. A tiny fire, hardly bigger than the palm of a hand, burns brightly as they sit with their backs to the towering Mexican mountains. They are the last people we, the canoeists, will see for the next four days.

Downstream from Maravillas Canyon the river trip begins in earnest. At first broad terraces, carved 10,000 years ago by an earlier, wider Rio Grande, are visible in the distance across the lowlands known as Outlaw Flats. But soon the walls close in; the river rams against a sheer cliff and swirls at right angles to the solid rock. In the course of a single mile it twists north, east, and south before emerging into the steep-sided chasm called Reagan (or Bullis) Canyon. This is the heartland of the Lower Canyons, a twenty-mile stretch of eastward-flowing water sealed off from the outside world by unscalable escarpments that sometimes reach a thousand feet in height.

The untrained eye perceives them as a sequence of visual delights: barrenness juxtaposed against fertility, white water followed by repose, colors constantly altered by the ever-changing light. But the natural scientist sees a methodical order beneath these images; the riverbed, the riverbank, the floodplain terrace, the boulder-covered talus slopes, and the sheer canyon walls capped with aeries. Within this unvarying pattern the life of the wilderness has organized itself.

By the vagaries of nature and by man’s indifference, the Lower Canyons remain a wilderness preserve. Relicts of the cooler, wetter Pleistocene continue to exist in their clefts, just as they do in the high altitudes of the Chisos, Davis, and Guadalupe mountains. Birds, some of them fleeing the impact of human settlement, find sanctuary here—herons, eagles, and white-wing doves among them—and the highly endangered peregrine falcon almost certainly nests among these crags. The canyons are a refuge for mountain lions and zone-tailed hawks. They are the only known location for the delicate, pink-flowered Maravillas milkwort and the tiny heather leafflower. They are among the few places where the pocketed freetail bat is found. And they provide an irreplaceable corridor through the Chihuahuan Desert for migratory birds. The richness of the canyon life stands in healthy contrast to the adjoining uplands, where overgrazing has devastated the once-lush grass that attracted ranchers after the railroad came through (twenty miles to the north) in 1882.

Midway through Reagan Canyon the human presence reappears in a setting of unparalleled beauty. Rounding a bend, one sees a minuscule building perched atop the loftiest of cliffs. This is the Asa Jones pump house, where man’s ingenuity succeeded in tapping the river through a series of pipes waggling crazily down the canyonside. Abandoned now, the pump house once supplied water for a rustic candellia-wax rendering “factory,” which, as the story goes, made Asa Jones a millionaire and let him quit this parched desert for the comforts of Alpine.

The pump house serves as a reminder of how few people have ever used the river in modern times. Trappers searched for pelts in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and river riders patrolled the banks after World War II to keep diseased animals from crossing north. Sport fishermen occasionally visit the lower end of the canyons today. But the ranchers on the uplands have kept their backs turned resolutely to it; there are lifelong residents of the adjoining property who have never once gazed down from the rim at the twisting green river.

On the grassy alluvial terrace below the Asa Jones pump house, however, it is easy to picture the encampments of Indians who once lived in harmony with the Lower Canyons. Their visits were apparently regular: Virtually every habitable site in the Lower Canyons shows some signs of occupation, and archaeologists doubt the canyons were ever completely devoid of human presence in the 10,000 years before the coming of European man. The evidence suggests a hunting-gathering subsistence with the campsites perhaps reoccupied on the Indians’ seasonal rounds.

The Indians who visited the Lower Canyons survived on freshwater mussels, land snails, and slow-baked sotol and lechuguilla. They ground the pods of honey mesquite to a pulp and used the flour for flatbreads and porridge. Fruits enlivened mealtimes according to the season, and flavorings for meats like rock squirrel and catfish could be obtained from oregano, Cimarron and Drummond onions. In the fall, the juice of sumac berries, mixed with honey, provided a refreshing drink. To the adventurous visitor willing to live off the land, these same foods are available today, along with such modern-day delicacies as white-throated wood rats, chicken-fried.

The hundreds of springs and seeps along the margins of the river not only create a flourishing microhabitat of sedges, rushes, and ferns where canoeists can find reliable supplies of pure water; they also insure that the Lower Canyons will never be menaced with the extinction that could face the upstream canyons if the Rio Conchos water were cut off. The mean discharge along the Rio Grande increases by nearly a third between Big Bend Park (927 cubic feet per second) and Langtry (1310 cfs), with most of the difference coming from these springs.

Two miles downstream from Asa Jones’ pump house, tucked away beside the rapids formed by the outwash of San Rocendo Canyon, is the most unforgettable of all the Lower Canyons’ springs: the great “bathtub” hot spring, the oasis of all oases for the weary canoeist. James McMahon, the trapper who was the first white guide who floated the Lower Canyons and lived to tell the story, led Robert Hill’s 1899 expedition here, and Hill, renewed, spent the next half-day soaking in the pool and washing his clothes. Surrounded by a hedge of reeds and floored with sand and smooth-sided pebbles, the sheltered pool is large enough to accommodate three or four bathers in a basin of gushing water. The temperature is warm enough that one does not flinch upon getting in, and cool enough that one never becomes overheated. It is perfection: people often linger for hours, paddling against the current or floating motionless like alligators.

Fourteen miles farther on, at the spectacular cliffs of Burro Bluff, the river again turns north and enters the most arduous stretch of the Lower Canyons. Upper and Lower Madison Falls come in quick succession, to be followed by the perilous, but runnable, Panther Canyon Rapids. One begins to realize how uneasy is the alliance that has been building between canoeist and river in the preceding days; no matter how familiar the waters become, nature and the river remain supreme.

In writing of the Lower Canyons, the temptation is always to particularize: to describe one’s own trip, one’s own experiences. But what is fundamental is not the particulars but the universal, the abiding river itself. That is what matters, and yet the particulars force themselves onto the page. On the last two nights on the river, these were the particulars:

At the campsite where San Francisco Canyon meets the Rio Grande, a sunset rich with orange, pink, and purple banks of clouds; a driftwood campfire shedding a faint light, like a few candles; canoeists talking softly in small groups, almost in whispers, nothing like the roaring campfire and storytelling of imagination; the mournful harmonica; nightfall with stars and no moon; Taurus, the Pleiades, and over the canyon, Orion setting; the utter peace that bonds men as surely as civilization’s ways divide them.

The last night at Pancho’s Cave, a rockshelter high above the river, hastily sought out as a 50,000-foot thundercloud bears menacingly down above Sanderson Canyon; golfball-sized hail covering the ground as if it were a snowfall; in the dry shelter, a dinner brewing in the galley; a gusty thunderstorm with every cliff and crevice in the canyons pouring out its separate waterfall; afterwards, a thin sickle moon, stars, and lightning and thunder receding for hours in the east: a pastoral coda.

The float trip ends two miles beyond Pancho’s Cave at Dryden Cable Crossing—a historic Rio Grande ford used by the Comanches and Apaches for forays into Mexico as late as the 1830s. Their trail was a mile wide in places and littered with the skeletons of livestock; it was, marveled one Mexican officer, “so well beaten that it appears that suitable engineers had constructed it.” At this historic spot, one picks up the thread of civilized living with hesitant, blinking eyes. The world has moved a week farther along in its concerns, while one’s own life on the river has stayed motionless, like the still point of a turning wheel. One leaves a world where everything is measured by sunrises and sunsets, and returns to a world where the day of the week, and the hour of the day, matter. “Has anyone dropped The Bomb?” a companion asks, and we turn on the car radio to find out.

- More About:

- Parks & Recs

- Longreads

- Big Bend