“Oh, my God, this is real.”

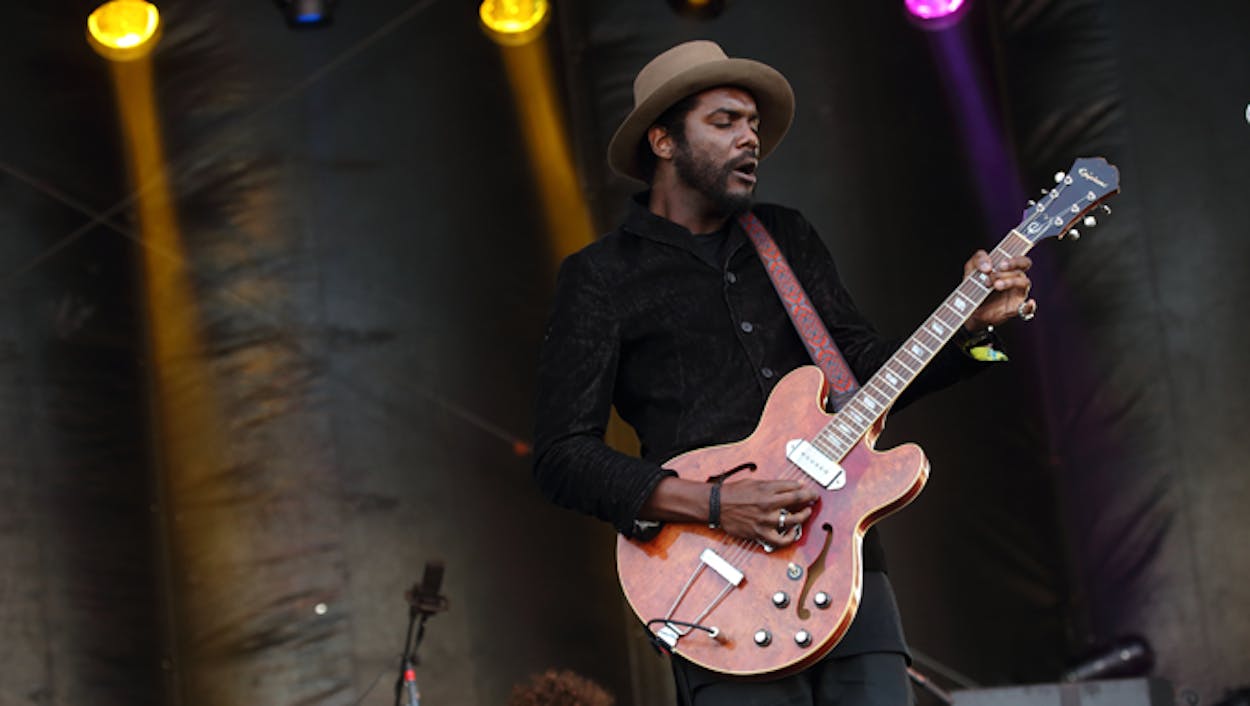

That’s what Gary Clark Jr. says he’s thinking when he’s standing in front of a huge crowd, like at Bonnaroo, Coachella, and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, or when he’s sitting in at stadium gigs with the Rolling Stone or Eric Clapton. Last year, in an interview conducted in Los Angeles, Clark told me that when he’s onstage and lets his mind wander, he often thinks back to the very first time he performed in front of an audience. The legendary Austin nightclub owner Clifford Antone invited a then-fifteen-year-old Clark to sit in with a who’s who of blues legends that included Pinetop Perkins, Hubert Sumlin, Calvin ‘Fuzz’ Jones, James Cotton, and Mojo Buford.

“He leaned into me and said, ‘You want to play? Then get up there and play,'” says Clark, who in January won his first Grammy, for “Best Traditional R&B Performance” for “Please Come Home,” a track from his Warner Bros. debut Blak And Blu. “The older I get, I’m like, ‘Damn. I was just a kid.’ And everybody was in the club that night—Jimmie Vaughan, WC Clark, Doug Sahm. All these people I’d studied on Austin City Limits videotapes were there. That moment is frozen in time for me. It was like, ‘Okay, I’m supposed to do this.’ Not just because I wanted to, but because somebody like Clifford Antone thinks it’s important for me to get up there.”

“And I believe that without that night, I’m not playing the White House or sitting in with the Rolling Stones. When I talk to Keith Richards about Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, my mind keeps going back to Clifford introducing me to the guys that played with those guys. For some crazy reason all these events, they don’t feel random. There’s definitely a correlation. If I wasn’t standing near Clifford that night, upfront, freaking out that these guys were there—if I was on the other side of the club—he wouldn’t have seen that excitement in us and wanted us to be up there. You never know. You just never know.”

Clark says it’s still humbling—still a pinch-yourself-achievement—that the Austin guitarist Jimmie Vaughan has looked after him ever since that night, not just offering to share the stage with him on countless occasions but to share his knowledge of the music business and life on the road. Especially since Vaughan and his younger brother, the late Stevie Ray, are two of Clark’s primary influences. In fact, when I called Clark a few weeks ago to discuss Stevie Ray’s influence on a generation of young guitar players, Clark was effusive in his praise of the guitar player that many lament still hasn’t made it to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame:

Andy Langer: I imagine you’d acknowledge it’s an understatement to say Stevie Ray Vaughan had a strong influence on your playing.

Gary Clark Jr.: Definitely. He’s a major influence on myself and so many others. You can still walk up and down Sixth Street here in Austin and hear a bunch of young guitarists playing Stevie Ray Vaughan licks. And then the other day, I met a 22-year-old in Melbourne, Australia, that was hugely influenced by Stevie. It’s a global thing. He’s one of the most powerful guitarists ever. He changed the way people play Stratocasters. I don’t know of any young guitar player interested in blues who hasn’t studied his licks and wanted to play as powerfully and dynamically as him.

I imagine it’s like how Stevie might have studied Hendrix.

GC: Exactly. I was watching YouTube clips of Stevie just a couple hours ago. I’m still trying to figure it out. And I can’t, which is frustrating. Everybody wants to be that powerful, but you can’t touch him.

And that’s what differentiated him—the raw power and force of the playing.

GC: Yeah. But you can’t really put your finger on it. It’s funny. You see the influence not just in the music, but the way he dressed. You see blues guys wearing Stevie’s persona like a uniform. There are guitar heroes and then there are icons. And he’s way up there at the top of that list. I think of Albert King, Hendrix, Buddy Guy, Clapton. Stevie was the most powerful and dynamic out of those guys. You could tell his influences, that he respected what came before, but he put these twists on them that made them his own. And that’s what people have been trying to figure out and analyze ever since. Maybe it’s the amps? Maybe it’s the pedals? Maybe it’s the Strat? Or the pickups. No, the dude is just badass. And you can’t touch him.

I think it’s interesting that you didn’t ignore or hide your passion for Stevie because being from Austin meant everybody else that was young and played guitar loved and worshipped Stevie. Your instinct was to embrace it, but not be it.

GC: When I first started playing guitar, a kid who lived next door gave me Texas Flood. It just so happened that the next Saturday, KLRU aired a Stevie retrospective with all three shows—the 83 set, the 89 show, and the tribute concert. I soaked that up and wore out that VHS, studying every lick. I wanted a Stratocaster. And pretty quickly, I realized I can’t get near that. I can’t play as fast as him. I can’t cop his tone. I said, ‘Let me try a hollowbody and see if I can figure something else out.’ But I never tried to run away from it. I think being from Austin made him a big influence. But Stevie was a great jumping off point, because I wanted to know what came before. It was great to have the best of the best as that primary influence.

You know Jimmie. You know Double Trouble. You couldn’t have known Stevie. But you’re as close as you can get to the source.

GC: My first studio experience was with Eve Monsees and Double Trouble—and that was just a few years after I got Texas Flood. And Jimmie used to take me on the road. It’s still kind of unbelievable to me. I remember being a kid in the front row watching Jimmie play La Zona Rosa, just soaking it up as a fan. To be accepted in that world at such a young age and be that close to it is still a trip. As much as I’ve been around Jimmie, it’s still weird for me. When we were in Australia a few weeks ago, he came to our show in Sydney. He walked backstage, and I just froze. It made me so nervous that he was there to check me out. Fifteen years later, I’m thirty years old, a grown ass man, and I turn into that kid at La Zona Rosa. It’s inspiring and motivating to have those guys back me up and show support. I’m grateful. I’m proud to be part of that lineage, but I still feel like I’m not in it. I’m on the outside, looking up. I think it’ll always be that way.