Every family has a saint; in mine, he’s certified. In the Eighties, reports began to surface of a young man in a red pickup truck bearing food and water who would arrive to help unauthorized immigrants stranded in the deserts of California, Arizona, and New Mexico. In some reports, the man appeared just in time to rescue people from drowning in the Rio Grande; in others, he made them invisible to the Border Patrol or protected them from rattlesnakes or advised them on where to find work. He wore a cowboy hat and boots, or he was dressed as a priest. When the grateful immigrants asked how they could ever repay him, the man told them not to worry. When you return to Mexico, he said, just go to Santa Ana de Guadalupe, a tiny village in Jalisco, and ask for Toribio Romo. The immigrants who did so were told that they would find Toribio in the local parish church. There at the church, they discovered a sarcophagus with Toribio’s remains, two small bottles with his blood now turned to powder, and the shirt he was wearing when he was assassinated by Mexican federal soldiers, in 1928.

One of the first written accounts of Toribio’s miracles was from a 45-year-old undocumented immigrant from Zacatecas named Jesús Buendía Gaytán. In 2002 he told a reporter from the Mexico City magazine Contenido about a strange experience he’d had two decades earlier. In the early eighties, Buendía had hired a smuggler in Mexicali, Contenido reported, “but as soon as they crossed the line a Border Patrol van spotted them and to avoid arrest Jesús escaped into the desert. After walking for several days in desolate trails, more dead than alive from heatstroke and thirst, he saw a truck approach. A young, thin man with light skin and blue eyes who spoke perfect Spanish got off the truck, offered him water and food, and showed him a place where farmworkers were needed.” The Good Samaritan told Buendía to look him up once he had a job and money; he was sent to the church in Santa Ana de Guadalupe. “I almost had a heart attack when I saw the photograph of my friend hanging over the altar,” Buendía recalled. “Since then I pray to him every time I set off for the United States in search of work.”

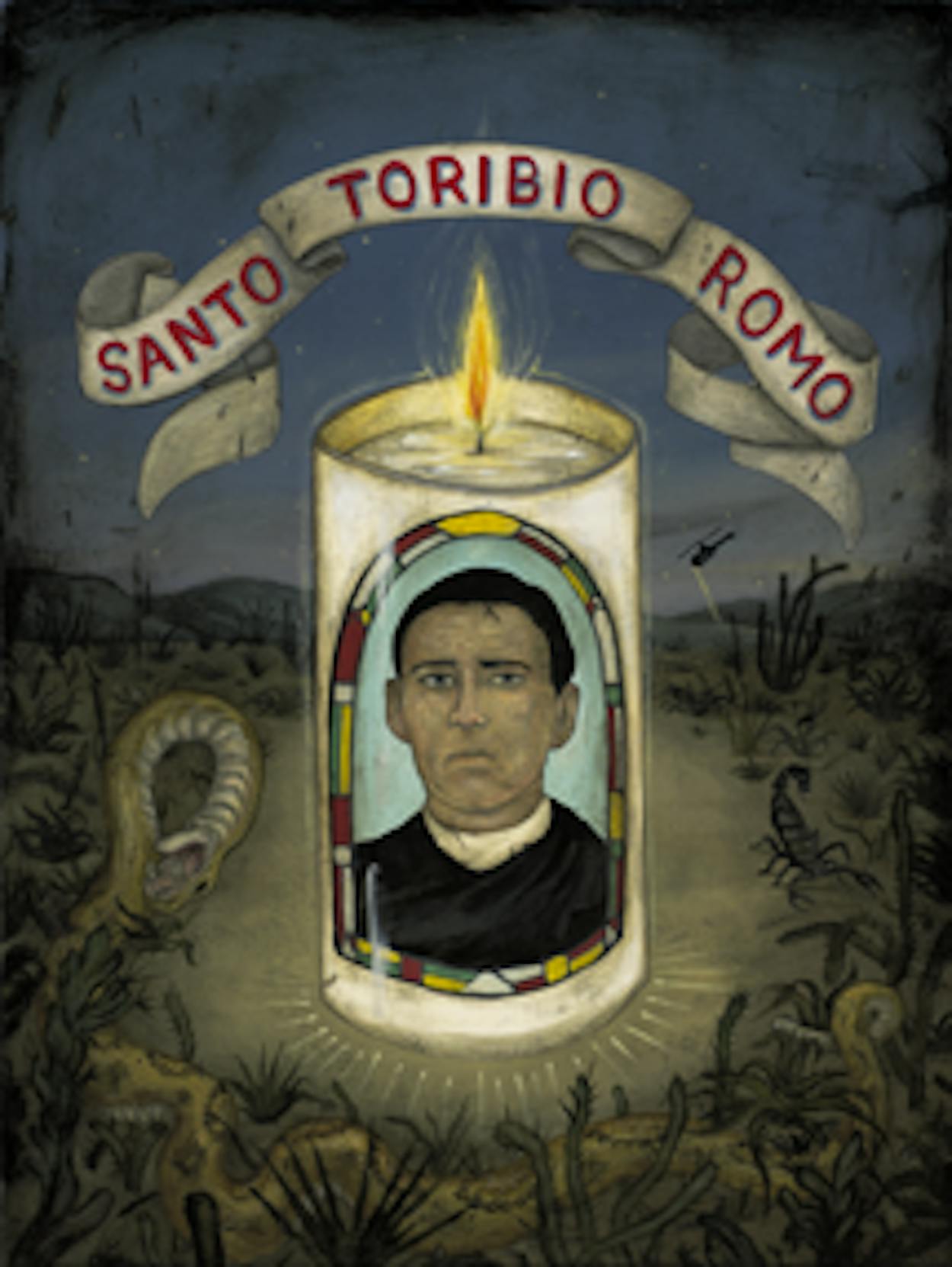

In Mexico and in many immigrant communities in the United States, Santo Toribio is a superstar among saints. No certified holy man has lent his name and image to as many restaurants, grocery stores, pharmacies, travel agencies, and employment centers. Toribio even has a brand of designer sneakers called Brinco ($215 in boutique stores). Border Patrol agents frequently arrest undocumented border crossers carrying scapulars and key chains with the image of this ubiquitous blue-eyed miracle worker. The official banner at the 2010 Jalostotitlán Expo features him above a glamour shot of Miss Jalisco and two other beauty queens with the slogan “The Heart of Los Altos de Jalisco, Land of Santo Toribio.”

About 300,000 religious tourists, many of them with license plates from California, Texas, Nevada, and Idaho, visited Santa Ana de Guadalupe this year to seek the saint’s aid before setting off for el norte or to thank him for his protection. The number has dwindled somewhat in the past couple of years, yet these pilgrims continue to leave behind notes, votive offerings, photographs, drawings, and retablo paintings that give testimony of Santo Toribio’s interventions. One testimonio poster shows a photograph of an eighteen-year-old woman with a message from her parents thanking Saint Toribio “for having granted us the miracle of finding the body of our daughter Maribel, who died in the desert of the United States.” Not far from it are several photographs of Mexican immigrants in U.S. military uniform asking Toribio to protect them during their service in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The little parish church has become crammed with these offerings. They are posted up along a wall of a church building that also serves as a devotional souvenir store. And at dozens of shops in town, visitors can purchase scapulars, key chains, pens, DVDs, comic books, and T-shirts with the image of Saint Toribio. The faithful can grab a bite to eat at the church-owned restaurant El Peregrino or buy lime popsicles at the Dulcería Santo Toribio across the street from a cantera stone statue of Santo Toribio.

The first time I heard about the saint in our family was when my aunts and uncles from California called my father to share the news of Toribio’s canonization by Pope John Paul II, on May 21, 2000. My father, who doesn’t believe in saints, shrugged it off. An avid Dallas Cowboys fan, he’d rather be related to Tony Romo.

Santo Toribio was never a subject of conversation in our immediate family. He was almost a taboo, a vestige of the past we had collectively left behind. The village of Santa Ana de Guadalupe is infused with my family’s history. In the early 1600’s the first Romos migrated there from Vivar, Spain, a small Castilian village where El Cid—Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar—was born. Four centuries later more than a third of the inhabitants are distant relatives who share my surname. Near Tío Toribio’s statue a woman sells pirated CDs with recordings of “El Corrido de la Tragedia de Santa Ana,” a folk song about a shooting in which my grandfather Agapito was killed when my father was two years old.

It was that tragedy, more than anything else, that drove my father to leave. In 1953, at the age of fourteen, he crossed through the Tijuana border without papers. He later became a U.S. citizen and resident of Texas, and for the most part stayed away from his hometown. For him, the land of Santo Toribio was full of painful memories of the fields where he had worked at the age of nine planting beans and maize from sunup to sundown with two burlap sacks strapped around his neck and of the home where his mother raised him and his four siblings after his father was killed.

My father never bothered to explain it to me, and I only recently learned exactly how I’m related to Toribio. The kinship terminology depends on what side of the line you’re on. In Mexico he’s my tío tercero, or simply, tío. In the United States, he’s my second cousin once removed. But the man who is said to come to the aid of immigrants in the desert not far from the border city where I now live has become increasingly difficult to ignore. The cult of Toribio has spread far beyond Santa Ana de Guadalupe. Many Catholic parishes in Latino communities throughout the United States have requested and been granted relics with the bone fragments of Saint Toribio, including churches in San Antonio, Chicago, San Diego, Sacramento, and Tulsa. In Sacramento, more than two hundred relatives of Saint Toribio gather each May to celebrate his canonization. In Tulsa, Toribio became a powerful political symbol against Oklahoma House Bill 1804, an anti-immigrant law signed in 2007 that, among other things, made it a criminal offense to give a ride to an undocumented worker. As Father Timothy Davison, a priest of the Tulsa congregation that declared itself a sanctuary for immigrants, told me, “The law created much hardship on those who have been building our economy. Our response was to build a shrine to Saint Toribio right in the middle of the country.” Recently, a Catholic church in Izmir, Turkey, obtained a relic from Santa Ana de Guada-lupe as well. Santo Toribio’s story resonates in a country with a long history of emigration to Germany and religious persecution of non-Muslim minorities.

As for me, I still haven’t figured out this relative of mine whom so many call a saint. I’m not sure what I think about Tío Toribio’s posthumous miracles and apparitions. Are they real? Where do they come from? Whenever I’m asked about my religious beliefs, I usually respond, only half-jokingly, that I’m a devout musician. But these days, when nuance and complexity are usually the first victims of the increasingly strident and disturbing debates about immigration, I too have turned to Saint Toribio—if not in search of a deeper truth, at least for a different way of looking at things.

One of the great ironies of my tío’s story is that like most of the Mexican Catholic priests of his day, Father Romo was fervently opposed to emigration to the United States. In 1920 he wrote a slapstick morality play titled Let’s Go North! The one-act comedy depicts a cultural clash between Don Rogaciano, an Americanized Mexican emigrant who returns to his village with airs of superiority, and Sancho, a sharp-witted campesino who never left. At first Don Rogaciano impresses the locals by flaunting his newly acquired English, proclaiming himself a lover of “progress and civilization” and denouncing the village priests as “money-grubbing retrograde obscurantists.” But by the end of the play Sancho beats the returning emigrant into submission with a cane and forces him to stand before the audience like a mannequin. Don Rogaciano, with his slicked-back hair, sweet-smelling cologne, and high-water pants, is the very embodiment of the corrosive influences that returning emigrants bring back from the other side—arrogance, irresponsibility, the loss of family values, materialism, and sexual ambiguity. If you betray your country and go north, Toribio’s play warned its Mexican audience, you might come back as a “rooster hen that neither crows nor lays eggs.” Or, even worse, a Protestant.

“Take a good look at what becomes of the Mexican who goes north,” Sancho says near the end of the play. “He ends up a man without religion, without a country or home . . . a coward, an afeminado who is incapable of feeling shame for having abandoned his responsibilities to his family. Despite this, the roads are packed with Mexicans headed toward the United States in search of bitter bread. Everywhere you hear the rallying cry—‘Let’s go north!’ ”

Six years after the play was written, many of Toribio’s fellow priests were themselves forced to go north to cities such as El Paso and Los Angeles to escape religious persecution, using the aid and networks of the same emigrants they had formerly denounced. The constitution adopted after the Mexican Revolution contained numerous anticlerical provisions, and in 1926 President Plutarco Elías Calles mounted a campaign to eradicate Catholicism from the nation’s public life. During the Cristero War that resulted, Toribio Romo was one of the priests who refused to obey the government’s orders for Catholic clerics to cease practicing their profession and their religion and relocate to major urban centers. He often wore a cowboy hat and disguised himself as a campesino in order to continue ministering to his parishioners. As the conflict grew more and more violent, the Los Altos de Jalisco region, where Toribio’s birthplace is located, became the epicenter of armed resistance.

The entries in Toribio’s journal from this period are fascinating. He scribbled most of them hurriedly on scraps of paper inside caves and abandoned adobe shacks while on the run from federal soldiers. In one entry he described his narrow escape after Calles’s troops raided a building where he and his clandestine congregation had been worshipping illegally. “The people screamed and started to run. Get out, Father, they’re here! Run!” Toribio wrote. “I had to violently cast aside the sacramental ornaments and run out through the streets with my heart beating frantically with fear . . . I jumped over fence after fence, all the while thinking I would be killed in punishment for my sins of cowardice and sacrilege, for I still had fragments of the holy host in my mouth.” Finally, on February 25, 1928, when Toribio was sleeping in a room inside an abandoned tequila factory he used as a chapel near Tequila, Jalisco, the government troops broke into his chambers and shot him to death.

Toribio’s efforts to prevent his parishioners from dislocating themselves to the United States ultimately proved ineffective. The first waves of emigration from Jalisco—one of three states with the highest loss of workers to the United States during the twentieth century—had begun in the 1880’s. That’s when the Mexican Central Railway connected the region to Texas and the U.S. borderlands, where there was a huge demand for Mexican labor in the construction of the railroads. The Cristero War, from 1926 to 1929, further depopulated the village, and by 1930 the population of Santa Ana de Guadalupe had been cut in half. By the sixties, most of Toribio’s relatives were long gone.

One of them was my father. Tío Toribio would have probably seen him as one of those border-crossing “traitors to the motherland.” After living in the United States for twenty years, my father, who had attended Catholic school until the sixth grade, became a Protestant.

This summer I decided to travel to the village where Toribio and my father were born. I believed Santa Ana de Guadalupe could offer another vantage point, a window into much broader histories, both personal and collective. I took a plane from El Paso to Guadalajara, where I visited church historical archives and dug up hundreds of pages written by Toribio—including his journals, plays, and sermons—that have never been published. From there I rented a car and drove to the land of Santo Toribio.

For several days I interviewed people in Santa Ana de Guadalupe. Almost everyone I talked to in the village had emigrated to the United States at one time or another. Father Gabriel González, the village’s 47-year-old parish priest, worked in Long Beach, California, for a few months on a tourist visa before entering the seminary. He prepared prepackaged food for airlines. Father González has been a major driving force behind the transformation of Santa Ana de Guadalupe into a booming religious tourist destination. Thanks to the income generated by sales of devotional souvenirs, special masses, donations from U.S. and Mexican parishes, and other fund-raising activities, he was able to build a retreat center, which includes 24 rooms for visiting priests and dignitaries, a meeting room, a prayer chamber, and an indoor swimming pool. A new church with a seating capacity of 2,000—to which Santo Toribio’s remains will be relocated—is under construction. The old church could hold only 150.

Not everyone in Santa Ana was happy with the new state of affairs, however. “All the blessings are for the peregringos [“gringo pilgrims”], and very little for those of us who have lived here all our lives,” complained one resident of Santa Ana de Guadalupe, who asked not to be identified. Others said that the priest has pressured local residents to sell or donate their lands to the church or move their homes and small shops away from the locations with the most tourist traffic.

I asked Father González about some of these criticisms in his office. He sat behind a mahogany desk under a large photograph of Santo Toribio. “This is not about commercialization,” he explained. “This is about providing a service for our visitors, not about making money or getting rich quickly. When I began my ministry here, in 1997, there wasn’t a single place where a visitor to Santa Ana could buy a taco. Now the church has three restaurants where they can buy a plate of carne asada for 25 pesos [about $2]. That’s a very reasonable price.” He insisted that the local inhabitants have also benefited from religious tourism. “When we construct new buildings, we could easily hire people from outside, but we prefer to give jobs to the people of Santa Ana,” he said.

Juan Romo, a distant relative of mine I met for the first time during my visit, told me that Santa Ana had never had a priest who had done so much for the community. Juan owns a plot of land along the main road that he’d turned into a parking lot and was thankful that it was now possible to make a living in Santa Ana. At 82, he could remember when his village had lost almost all its young people to emigration and only the old remained. He was one of those who went north to work on American farms. All he could earn working in the cornfields was one peso a day. Six times he’d gone north, beginning in 1948.

Juan was a “bracero.” Under the Bracero program, which lasted from 1942 to 1964, a certain number of temporary contract workers from Mexico, like Juan, were permitted to enter the United States every year. But in 1948 the government of Mexico had refused to assign braceros to Texas due to violations of the binational guest-worker agreement and racial discrimination. Mexican federal troops were assigned to Juárez to stop the flow of emigration. In a strange switch, the U.S. Border Patrol actually helped thousands of “illegal” workers wade across the Rio Grande into El Paso. That was how Juan first came to the U.S. The migra transported him along with the other laborers to the Texas Employment Commission, where they were assigned to the state’s unpicked cotton fields.

Juan ended up in San Benito, but, despite the desperate need for workers, he didn’t even earn enough to pay his bus fare back home. “They were very crooked—muy rateritos—in Texas,” he told me. “The farmers would cheat us by fixing the scales so that when we brought our ten-pound bags of cotton to weigh, the scales would hardly move from the zero.”

My second cousin Antonio Jiménez Romo told me a similar story of emigration and return. He first crossed the border illegally into the United States in 1992, the year Toribio Romo was beatified. Antonio left Santa Ana when he was nineteen years old because the only thing he could do there was milk cows, a job that paid miserably. He and his brother Toribio hired a former midwife from the nearby town of Jalostotitlán to smuggle them across the line into California. His mother sewed Father Toribio stamps inside their clothing to keep them safe. Antonio found work in restaurants in Venice and stayed there for nine years. “I had two jobs and was taking home almost three thousand dollars a month, but I was killing myself, working from six a.m. to midnight,” he tells me. “I came back to visit once and saw that people here make less money but they enjoy life more. Father Gabriel offered me work, and I decided to stay.” He’s now a tour guide for the church museum.

The posthumous cult of Toribio Romo has done what he failed to do in life: slow down emigration from Santa Ana de Guadalupe to the United States. The economy of this ranching village of 390 people had historically depended on the migradólares de los hijos ausentes—the remittances of the “absent children”—to stay afloat. Not anymore. Since his canonization (and commercialization), many of the saint’s relatives have been able to return to his village. It’s almost as if they are heeding Toribio’s invitations to immigrants stranded in the desert to visit him in the land of his birth. Some, like sculptor Jesús Romo, come just to visit. Others, like my cousin Alfredo, who built a home in the village with the savings he earned working for 32 years at the sanitation department in Palo Alto, California, have come back to stay.

Not everyone who returns to the land of Santo Toribio does so by choice. There are those who are forced to return because there were no miracles for them in the desert and those who did not experience the unsolicited kindness of a total stranger. But sometimes the return itself is the miracle. Father González tells the story of a woman who shared one such account with him. Her two sons from the town of San Ignacio, Jalisco, asked her to go to Santo Toribio’s parish to pray for his intercession before their crossing into the United States. A few days later, the mother came back to Father González with tears of gratefulness. She said her sons had encountered a man at the border who they believed was Santo Toribio. He told them that they would not be able to cross over and that their parents were worried for them.

Santo Toribio told them to go home.