According to the calendar, this blistering summer day is July 20, but inside Jim Lehrer’s office at WETA-TV in Arlington, Virginia, today is Bosnia, Whitewater, and Waco. The former Dallas newsman, who has co-anchored The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour on PBS since 1983, marks the passage of time by the big stories that get feature treatment on the program. Although it is still a few minutes before noon, the day’s lineup has already been determined at the regular morning conference call with coanchor Robert MacNeil in New York. This approach of examining a few subjects in depth, so different from the parade of soundbites on the major network newscasts, has been the hallmark of the MacNeil-Lehrer team for twenty years. But this month MacNeil will retire, and on October 23 the name of the program will change to The NewsHour With Jim Lehrer. What I had come to ask Lehrer was whether anything else will be different, as a result of either the shift in personnel or the recent attack on public broadcasting by the Republican Congress.

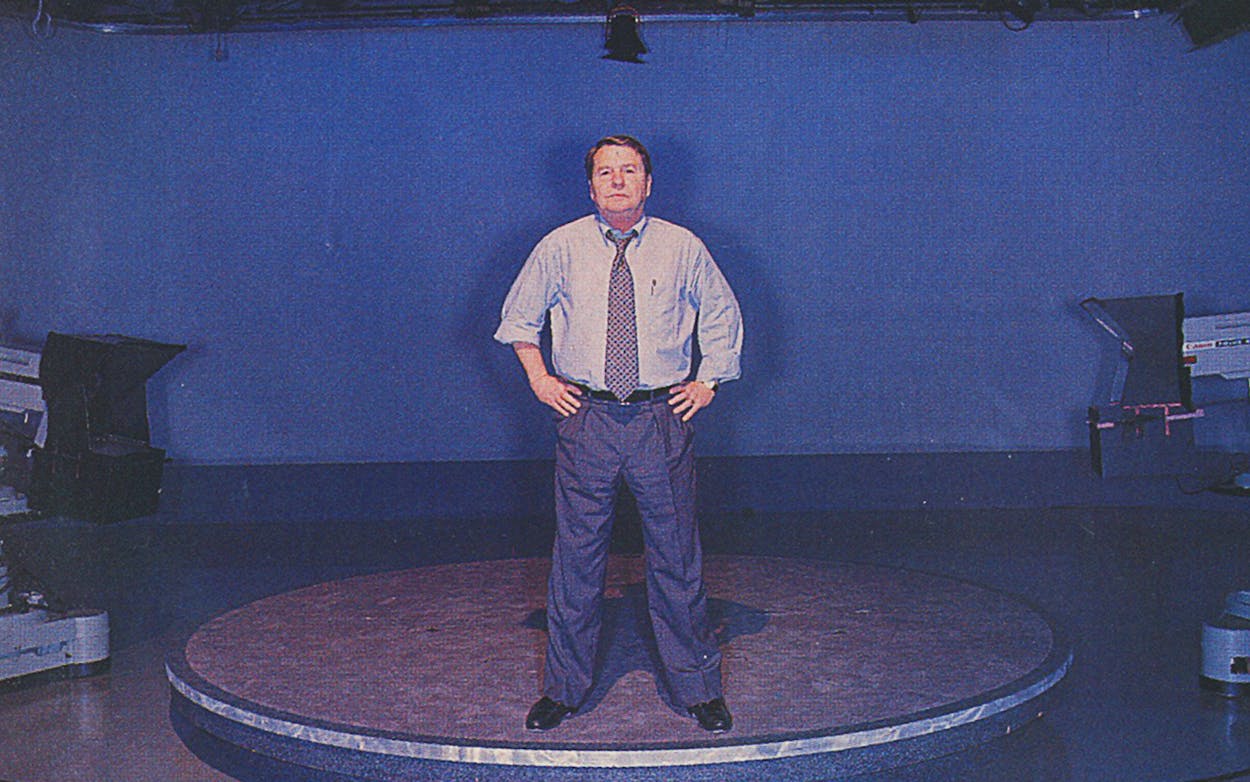

“We’re not going to move away from hard news, if that’s what you mean,” Lehrer says. We are sitting around a coffee table in an office that is large but not lavish. It is obvious that programming isn’t the only difference between news at PBS and news at the major commercial networks. WETA’s two-story brick building in the suburbs is far removed from the high-rent district in downtown D.C., where the network news divisions have their offices. The view from Lehrer’s window looks down on a street so obscure that the receptionist advises visitors heading for the building to call a Red Top Cab because it’s the only company that can be counted on to find its way here.

“The network newscasts are losing audience share,” Lehrer continues. “We’ve doubled ours in the past five years. People keep asking me if we’re going to be more like them. I wonder why one of the networks doesn’t decide that it has nothing to lose by being more like us.”

For those of you who are not among the 35 million viewers who tune in to the program at least once a month, being more like MacNeil/Lehrer means more than giving lengthier treatment to individual news stories. The format also involves interviews, debates, panel discussions, and quirky taped pieces picked up from news services around the world. If you happen to be interested in whether South Korea harbors greater resentment toward Japan or a more recent invader, China, you could have found out by watching MacNeil/Lehrer before the fiftieth anniversary of V-J Day (it’s Japan, by the way). Even the long features can be somnolent: I doubt that many people were gripped by a mid-August report of sweatshop conditions in the garment industry. Such esoterica are the main reason why the hard-core audience that watches the show every night averages only 5 million people — about half the average network draw.

But, of course, ratings don’t matter. Free from commercial restraints, MacNeil/Lehrer doesn’t have to be designed for mass consumption. In an era when the trend of TV journalism is toward sensationalism and confrontation — gotcha questions and salacious subjects, Inside Edition and Hard Copy, The McLaughlin Group and Crossfire — the real distinguishing feature of MacNeil/Lehrer is its civility. Anchors and guests alike behave as if their mothers were watching. They don’t raise their voices or interrupt or show off. This is especially true of 61-year-old Lehrer, who conducts an interview the old-fashioned way, like a basketball referee tossing up a jump ball and then getting out of the way. His lowkey, reflective demeanor off-camera is the same as it is on-camera, and his deep-set, rather sad eyes add to his air of a man holding fast to old values.

So do the artifacts in his office: a hodge-podge of bus memorabilia that Lehrer says is only a fraction of his entire collection. Paper buses, plastic buses, and metal buses fill the shelves; prints and photographs of buses occupy the walls. His father ran a small bus line in Kansas, where Lehrer was born, and moved to Beaumont to manage a depot when Lehrer was twelve. Lehrer’s proudest possession is a highway bus from the postwar period — a 1946 Flxible Clipper, to be precise, and if you think “Flxible” is a typographical error, you don’t know buses — that he keeps on his farm in rural Virginia. He showed me a snapshot of the bus, its squat shape and rounded rear end testifying to the truth of the adage that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and pointed to a barn in the background. “I usually kept it inside,” he said, “but thank goodness it was broken down at the time. The barn burned down just after this.”

Influences from the past shape Lehrer’s ideas about the media as well. After journalism school at the University of Missouri and three years in the Marines, he worked for the Dallas Morning News and, later, the Dallas Times Herald. Even today he thinks of The MacNeil/Lehrer News-Hour as a newspaper for TV. “The long stories are our front page,” he says. Lehrer is still an old newspaperman at heart, someone with a high regard for hard news, objective reporting, and the written word. His apprenticeship came at a time when every reporter, it seemed, had an unfinished novel in his desk — but Lehrer actually finished his, called Viva Max!, and it was later made into a movie. (Since then he has written seven more novels — including the just-published Last Debate, about celebrity journalists preparing for a presidential debate — as well as three plays and two memoirs.) Lehrer quit the Morning News when the paper, then in its hard-shell conservative heyday, killed his story about civil defense workers who were handing out anticommunist propaganda instead of information about how to prepare for a nuclear attack. After working for the Herald for nine years, he left journalism briefly to write fiction full-time, then returned in 1970 as the host of Newsroom, the nightly newscast at KERA, the local public television station. Newsroom made Lehrer’s career. Unburdened by the pro-establishment stance of the newspapers, it probed areas, like school integration and police brutality, that Dallasites weren’t used to hearing about — certainly not in such detail.

“Dallas was a great place to work,” Lehrer says. “There were incredible characters at the courthouse and city hall, and they would talk to you about anything. When everybody in town wanted to turn the Trinity River into a barge canal, I remember that the mayor, Erik Jonsson, told me, “The port of the future is a new airport. It will do for Dallas what the Ship Channel did for Houston’. A lot of people thought he was crazy, but while they were arguing about it, he went out and sold the bonds, without anyone really giving him the authority”. Lehrer shakes his head, amazed at the memory. That’s not the way things happen anymore — in Dallas or anywhere else.

In 1972 PBS tapped Lehrer to come to Washington as its public affairs coordinator, and the next year he joined former NBC and BBC correspondent Robert MacNeil for gavel-to-gavel coverage of the Watergate hearings. In 1975 they collaborated on a new half-hour show devoted to a single topic; eventually, they became coanchors. In 1983 both the time and the number of topics were expanded, but the show remained fundamentally the same. They deliberately haven’t carved out areas of specialization, although Lehrer says that MacNeil has always handled the lion’s share of foreign news: “When we started, he’d been everywhere and I’d been to Nuevo Laredo.”

If Lehrer’s experience in Dallas is a major reason why NewsHour will remain fundamentally the same after MacNeil retires, another journalistic influence from his past will bring about a change. “Remember how the networks used to have repertory companies of reporters?” Lehrer asks. “Look at CBS when Walter Cronkite was anchor. You didn’t watch CBS just to hear what Cronkite had to say. They had Dan Rather, Roger Mudd, Bruce Morton . . .,” and he reels off more and more names. “Most people probably couldn’t name three reporters for CBS today.” I keep quiet. Lehrer discrectly breaks the silence. “That’s a direction I’d like to go in, to build a repertory company so that viewers know they’re going to hear Paul Solman on business or Charles Krause on foreign affairs. I don’t think anybody is going to tune in just to listen to me talk for an hour.”

It would be out of character for Lehrer to engage in slamming the competition or, to put a kinder face on it, media criticism, so he does not say the obvious: that the networks have elevated their stars to the prime time newsmagazines while cutting back their reporting staffs because of budget cuts. But what about reductions at PBS demanded by the Republican Congress, which last spring had targeted the network for a 30 percent drop in federal support? Even as we speak, I can hear the sounds of boxes being dumped in the hall as part of the money-saving relocation of the New York news office to Washington.

“I don’t really think we’ve got a problem,” Lehrer says. “The momentum has gone out of that. Public broadcasting has too broad a constituency.” Like most PBS programming, MacNeil/Lehrer receives outside funding, in this case from Archer Daniels Midland, the politically controversial food giant, and New York Life Insurance.

Lehrer has another appointment scheduled and then he has to take his regular afternoon nap, so the interview is drawing to a close. I have one more question to ask: Does he have a favorite episode of MacNeil/Lehrer — a journalistic coup to match the time in 1979 when Roger Mudd of CBS asked Ted Kennedy, in effect, why he wanted to be president and Kennedy couldn’t come up with an answer? Lehrer politely demurs, but it’s clear that he doesn’t think much of the question. While The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour has won seven Emmy awards, it is not the kind of program that aims for greatest hits — nor is Lehrer that kind of journalist. “Well,” he finally says, “we did have the first long interview with the Ayatollah Khomeini, when he was still in Paris.”

The program’s ultimate importance is that it gives full, fair treatment to the biggest stories of the day, whatever they are. On the day of Mickey Mantle’s funeral, I saw a soundbite of Bob Costas’ eulogy on CNN and wanted to see more. My hope was that The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour would have the whole address — and it did. The only program of comparable quality is ABC’s Nightline, which borrows heavily from the original MacNeil/Lehrer format. But Nightline has to worry about beating Jay Leno and David Letterman, and so, Jim Lehrer points out, it devotes a lot of time to the O.J. Simpson trial. A point of pride with Lehrer is that MacNeil/Lehrer had only three Simpson stories during the first seven months of the trial.

“On the first day of the trial,” he says, “we gave it thirty seconds.” Who says MacNeil/Lehrer doesn’t do soundbites?

- More About:

- Dallas