Stories in this article are featured in episode two of our podcast America’s Girls. You can dive deeper into the stories from the show in our Pocket collection.

Subscribe

I was heading out to Shannon Baker Werthmann’s home in North Dallas, and I was running late. Like, exceedingly late. I was scrambling to finish a story on deadline, and my apology texts were getting embarrassing. A thirty-minute delay became an hour became two. This was no way to meet a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader—especially the golden girl of the late seventies. Lateness was a cardinal sin for the cheerleaders; they could get benched for showing up even a minute late. And so my heart was pounding as I stood on Shannon’s doorstep in my ankle boots with three-inch heels, trying to balance two armfuls of audio equipment as I pressed a buzzer that went ding-dong.

“I am so sorry,” I blurted when she opened the door wearing fuzzy rainbow slippers.

“I made us some tea,” she said, pointing to the couch where two mugs sat on side tables. We took a seat, and she asked me to tell her about the story I was writing. Shannon had been a broadcast journalism major at Southern Methodist University, and during our previous conversations, I noticed how much she liked hearing about my work. As the two of us chatted, I kept noticing those fuzzy slippers.

“Do you mind if I take these off?” I asked, pointing to my high-heeled boots. I’d been trying to impress her. Shannon had been on posters and commercials and merchandise through the late seventies, one of the most visible members of the squad.

“Please,” she said, and I kicked off my heels and made myself at home.

Actually, I met Shannon many years ago, way back in 1990, when she choreographed my high school musical. I was sixteen. I can’t remember how I learned our choreographer was a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader, but information like that has a way of spreading. Boys in class were suddenly curious about my after-school drama practice. So, y’know, what’s your choreographer like?

Shannon was pretty no-nonsense back then. She taught me how to fan kick my legs across the sturdy, bent knees of a boy, a trick I didn’t know I could do. I had no dance training, but I had secret dreams of being a star. I had this fantasy she would pluck me from the group, tell me I was special. Maybe you should try out for the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, she would say. Shannon was only two inches taller than me, at five foot four, and though she was more petite, I was a teen girl with Lean Cuisines in her freezer and dreams of transformation. I had Kathy Smith aerobics videos and SlimFast shakes on my side. You know the drill. Just ten more pounds, and I’ll be happy.

One day in my senior year, Shannon came to my drama class to teach a unit on stage combat. We learned pratfalls and how to fake-stab someone with a knife, and I found it tremendous fun to tumble to the ground, or keel over with a pretend wound in my side. On my way out the door, Shannon pulled me aside. This is it, I thought, as her hand guided me from the flow of traffic. This is when she’s going to tell me to try out for cheerleader.

“I really think you could have a future in stage combat,” she said. Stage combat?!

Shannon laughed when I recounted this story to her. “Did you really want to be a cheerleader?” she asked.

“Probably not,” I said. “I just wanted you to think I could.” I was a smart girl who wanted to be told she was pretty. We all want the compliments we don’t get.

Shannon was only seventeen when she auditioned for the cheerleaders in 1976. Candidates were supposed to be eighteen, but Shannon lied on her application. The early cheerleaders are better known for beauty than dance talent, but Shannon had both. As a little girl in Dallas, one of her hips was higher than the other, and her orthopedic-surgeon father suggested dance classes might help. They did. They also revealed a preternatural gift. At six, her ballet teacher put her in pointe shoes, and she lifted up on her tippy toes and crossed the room, the kind of thing you don’t generally try until a dancer is ten or so. At nine, she won an audition to dance with the Bolshoi Ballet. The following years brought summer opportunities in Germany and New York, where the teachers were not so nice. They said ugly things about her weight. She remembers eating two slices of Muenster cheese and a Diet Pepsi at a New York deli for dinner many nights. But by the time she was a teenager, two truths of her body had been revealed: she was short, and she had big breasts. The life of a ballet dancer would not be hers.

“I can’t imagine my life without dance in it,” Shannon told me, as she recounted this part of her story. She was now sitting on her bed, where we had determined we could get the best audio. Her fuzzy slippers rocked back and forth. “It’s like if you ask somebody: How would you feel if there was no music in your life?”

So Shannon enrolled in SMU, but she tried out for this thing called the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. She’d heard they needed dancers. She remembers being told to show up in a crop top and hot pants.

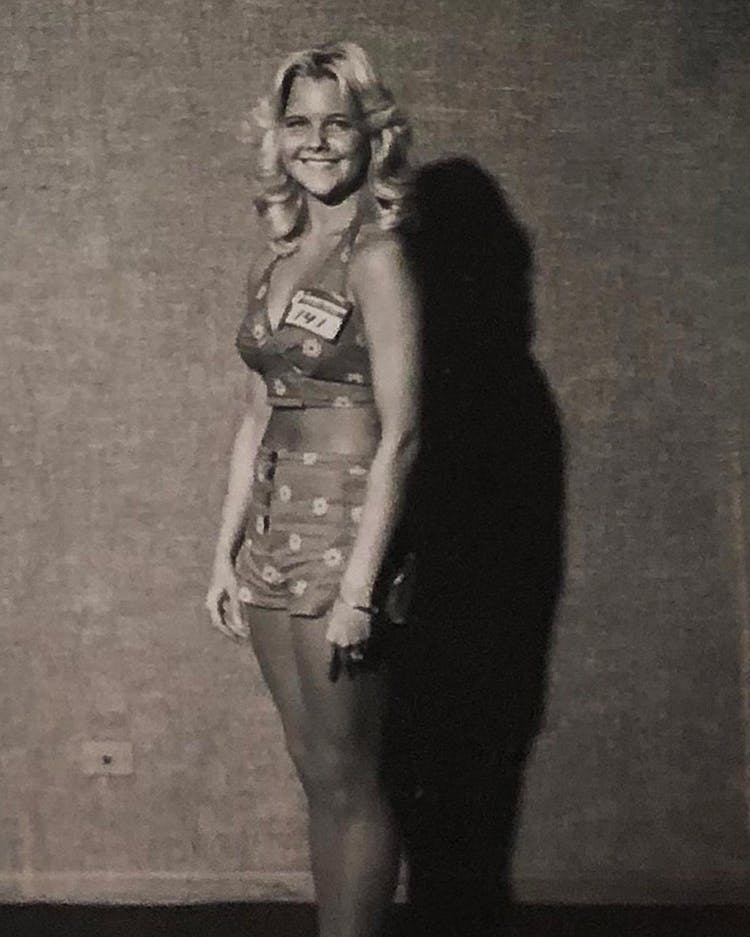

“Look at this little nugget,” she said, pulling out a black and white picture from her first audition. She looks so young. She’s standing stick-straight and smiling in a way that’s more reminiscent of school pictures than pinups. “She’s about as unsexy as you can be. I don’t even know if she’s cute.”

“Oh, she’s cute,” I said, taking the photo into my own hands to snap a picture.

Shannon had a funny relationship with the word “sexy.” Maybe we all do. The squad exploded during her years as a cheerleader (1976–80), stirring up controversy over sex and pop culture, and I think she got tired of answering questions about that particular topic. No, I don’t feel exploited. No, I don’t think of myself as a sex object. She and I had long conversations about what it meant to be sexy, the erotic force that travels through a woman’s body versus a pose you put on. She showed me pictures of herself in which a sexy look did seem a bit forced. But I showed her a photo of her dancing that I kept pinned above my work space at home, in which I thought she looked effortlessly sexy. Because she was inhabiting her body. She had such ease.

“If part of me, as a woman, was being sexy, then I was flattered by that,” she told me. “If that was all they saw, I did have some trouble with that. Being an image, sometimes that’s all they saw.”

Shannon’s image was everywhere by her third year on the squad. Because she could pull off a grand jeté, she was photographed doing dance moves. Because she had those classic all-American looks, she was featured on posters. Because she was an honors student at SMU, she was a spokesperson with the media. She got more fan mail than anyone else on the squad. (We read some of it in episode two.)

And for this, she was paid $15 a game, $14.12 after taxes. It was such a nominal fee she didn’t even cash her first check. She kept it as a souvenir.

“There were so many broke cheerleaders,” she told me. Shannon lived at home, with her parents, but other women had to scramble to make ends meet. “It was all fine and good at the beginning, but then when you can’t pay your rent for multiple months and you’re falling asleep at your desk at work because you’ve been working all night at rehearsal, and you’re seeing all of this wonderful publicity around you, and you think, for sure I have a place in this mix, monetarily. But where is it?”

They were told there was no money. That’s what then-director Suzanne Mitchell repeatedly told them: no money. And okay, this was before the lucrative sponsorships that are now commonplace for the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, and many cheerleading squads run in the red, but consider that the 1977 poster made $3 million for the Dallas Cowboys. According to court documents, the five women who appeared on that poster made $150 each. By my calculations, that leaves $2,999,250 to go around.

Shannon told me she’d been thinking about college athletes lately. The NCAA had just changed a rule that allowed them to profit off their likenesses. That got her attention.

“So I’m looking back now as a 62-year-old woman, seeing how many times my picture was used.”

I was sitting beside her on the bed, photos and newspaper clippings and fan mail scattered between us. “Shannon, you were used to sell everything from, like, cars . . .”

“Cups, hats, frisbees, cards, calendars.”

“Dolls, clothes.”

Some of these she got paid for, usually $500 an appearance. Many of these she did not.

I couldn’t tell if this bothered her. Probably she was looking back at an innocent time with less innocent eyes. Who doesn’t? But I was bothered on her behalf. The Cowboys were hard-core about copyright violation. They sued multiple times to protect the sanctity of their uniform. (Wait for episode three.) I came across a Dallas Times Herald article from 1980 about Suzanne Mitchell walking through a local arts bazaar and spotting a desk decoupaged with a picture of the cheerleaders. She asked if they had a license. For a $40 desk! The newspaper story about that encounter was illustrated with a picture of Shannon. Of course it was. Her image was used over and over in the media, and they didn’t have to pay her for that either. She loved what she was doing. Of course they could get away with it. But that doesn’t make it right.

Shannon’s time on the squad was also kind of a dream. She cheered in two Super Bowls. She was featured on the 1978 and 1979 posters. She appeared on The Love Boat, where she met Ginger Rogers, who asked to do a little soft-shoe with her. (Ginger Rogers!) But when I asked what her favorite memory was, she surprised me. She stared into the distance for a long time and said, “I went on an appearance with Roger Staubach.” At the time, she was the choreographer for the cheerleaders, having been hired in the early eighties to replace the squad’s original choreographer Texie Waterman. “We had to wait, and we sat in his car, and we talked about the bombing in Beirut.”

Two things strike me about this anecdote. One is that it has nothing to do with the glitz and glamour of the cheerleaders’ brand. The other is that it never would have been possible if she were only a cheerleader, since they aren’t allowed to fraternize with players. The best moment of her tenure only happened because she became an employee. But it meant so much to her. That someone she admired so deeply wanted to hear her thoughts on the world.

Shannon remained choreographer on the squad through the eighties. She was the first cheerleader ever hired by the organization after retiring her uniform. But the ground started to shift in 1989, with the regime change brought on by Jerry Jones. Current director Kelli Finglass took over the cheerleaders in 1991.

“I came in one day, and my stuff had been put in a storage room,” Shannon told me. Kelli had moved into her office. Shortly after that, she learned Kelli was hiring then–assistant choreographer Judy Trammell to replace her. She was fired, effective immediately. The cheerleaders had been a part of Shannon’s life for fifteen years—and then, she was gone.

“Disrespectful, unprofessional, and unbecoming of a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader director” is how she describes that episode now. “But big picture, she did me a favor,” Shannon said.

It was dark when we wrapped our interview. Shannon’s husband Craig was out of town, so it was just the two of us in her pretty two-story home. Her children are grown, with children of their own. She has a son and two daughters, both of whom became dancers. One toured in several Broadway productions out of New York. The other became a Rockette. Dance was a part of all of their lives.

“I never showed you the Osmonds special,” she said.

I gasped. “You have the Osmonds special?” I’d looked all over YouTube for that. The two of us stood across from her laptop in the kitchen, me in my socks, and her in those fuzzy rainbow slippers, and we laughed as we watched the ancient dispatch from the Pleistocene era of ye olde variety specials, which is to say, 1978. (“With special appearances by . . . Jimmy Walker! And the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders!”)

It’s a goofy performance. The cheerleaders lip-synch “We Are the Champions” as a football stadium is green-screened behind them. Their hips sway side to side, shoulders thrusting forward on the beat, eyes narrowed in a look that is maybe sexy, maybe silly. A group of beautiful young women who are mostly grandmothers now.

“What were you thinking?” I asked her.

“Oh,” she said, smiling at her younger self. “I was having the time of my life. We’d made it.”

Fun, glamour, celebrity. It’s no wonder I’d grown up wanting to be like those cheerleaders. And Shannon was the kind of cheerleader who made me feel like that was a good thing.

Hear more about Shannon; her best friend on the squad, Tami Barber; former squad director Suzanne Mitchell; and the ups and downs of fame in episode two of “America’s Girls.” Find it on Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

- More About:

- Sports

- Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders

- Dallas