This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The Dallas Cowboys owe much of their success over the years to an Indian. He is not a spy inside the Washington Redskins’ organization. Nor is he a mole hidden away on the staff of the Kansas City Chiefs. No, this Indian isn’t that kind of Indian. He is a real Indian.

He grew up near New Delhi.

The Indian joined the Cowboys way back, almost at the very beginning. He showed them how to use computers to become pro football’s first high-tech organization. He helped them put together their championship teams. Then the Cowboys drove him out of the franchise. The team went into a decline. But this year he has rejoined the Cowboys and promises to restore the glory days when the Cowboys always seemed to be a step ahead of the rest of the National Football League.

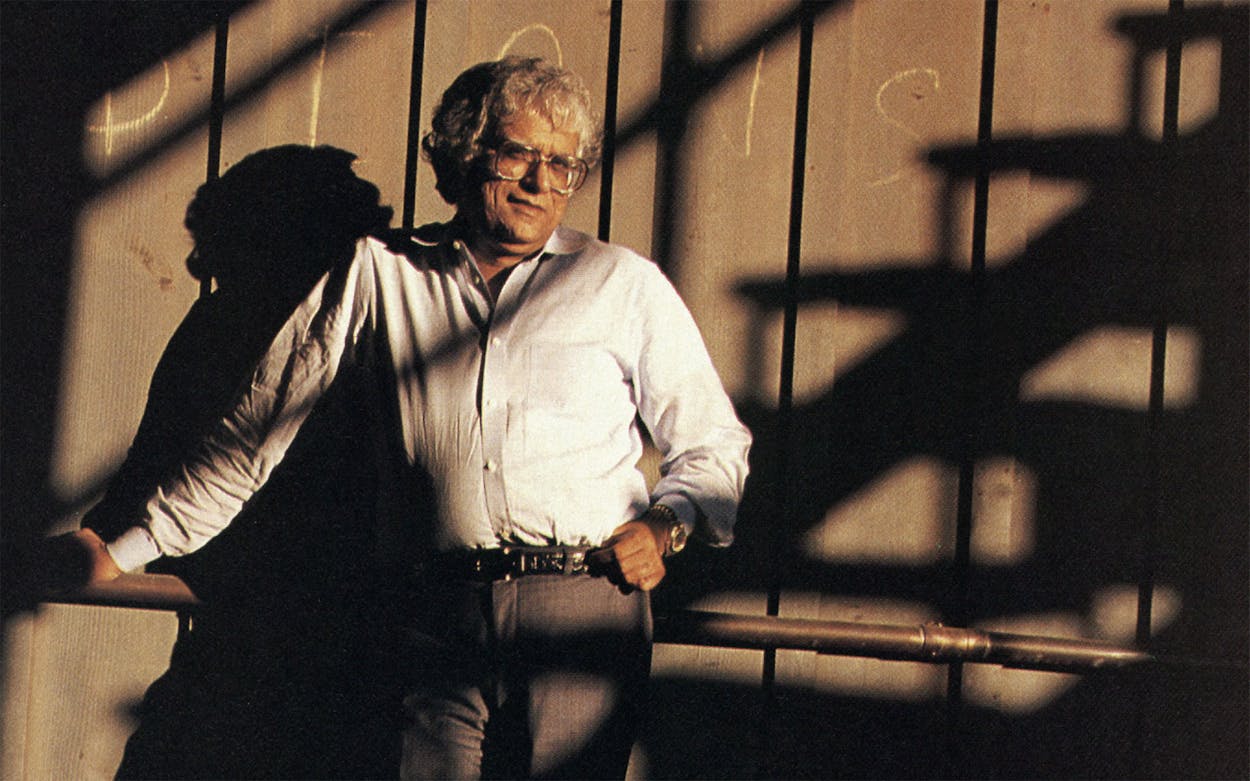

The Indian’s name is Salam Qureishi, and once more he is at the head of the team’s vast computer operations. With his smart software, he helped the Cowboys round up talent in the NFL player draft last spring.

It’s about time. The Cowboys’ drafts in recent years have been embarrassingly bad. The names of disastrous first-round draft choices like Rod Hill and Larry Bethea scare up memories of punts fumbled, tackles missed, and games lost.

Last spring, Qureishi supervised his first player draft since rejoining the Cowboys. He helped them pick Mike Sherrard (their first-round choice) and Tony Flack (their last-round selection) and everyone in between. And he has other plans for the Cowboys’ computer. He wants to get his computer onto the field and into the game. He foresees the day when it could call all the Cowboys’ plays.

“Football is too complex for humans to play,” Salam Qureishi explains. “They need computers.”

In the summer of 1959 an oilman named Clint Murchison was working to bring a professional football franchise to Dallas. He planned to call his dream team the Dallas Rangers, of all things. That same year Salam Qureishi left India to come to America. He had won a teaching fellowship at Case Institute of Technology. So the future hope of the Dallas Cowboys began his American life in Cleveland.

About the same time, Texas Ernest Schramm heard about Murchison’s plan for a new football franchise in Texas. And he wanted to be a part of it. At the time, Tex was living in New York City, where he worked for CBS Sports. But before joining CBS, he had been part of the Los Angeles Rams organization for ten years, moving up from public relations to general manager. Schramm asked a friend in Dallas to intercede with Murchison on his behalf.

When Tex reached Dallas that fall, he met with Murchison, who still didn’t have a franchise but seemed confident of getting one. Tex said he would like to work for Murchison and outlined his credentials. A few weeks later Murchison called Schramm and told him, “You’re on the team.” So now Tex had two jobs.

Schramm started signing up football players, even though the Cowboys didn’t officially exist. “I called the league office and asked them to send me some standard contracts,” Schramm says. “The league said, ‘No. You don’t have a franchise.’ So I printed my own just like theirs, same type, same paper.”

In January 1960 Tex Schramm called a news conference to announce that the Dallas Cowboys, who still didn’t have a franchise, had signed a head coach: Tom Landry. Since the job looked a little shaky, the new coach’s contract had a long section giving Landry the right to sell insurance in his spare time.

Later that month the National Football League owners met in Miami Beach to try to decide, among other things, what to do about the pesky city that kept clamoring for a football team. George Preston Marshall, who owned the Washington Redskins, wanted Dallas to wait a year. That was when Murchison, who had no intention of waiting, made his celebrated move of buying the rights to the Redskins’ fight song. Which happens to be the only good fight song in professional football. It’s the one that goes: “Hail to the Redskins/Hail victory/Braves on the warpath/Fight for old D.C.”

Marshall wanted his fight song back. Otherwise it couldn’t be sung at Redskins’ games anymore. And Murchison, the old horse trader, wanted his team. They made a deal: the franchise for the fight song.

So the Dallas Cowboys, who already had players and a coach, were finally officially born.

Meanwhile, Tex Schramm’s job at CBS was about to have a profound effect on the Cowboys. He was responsible for putting the Olympics on television for the first time in history. Previously, the Olympics had been covered only in short segments on the evening news, never as a show in and of themselves. But the 1960 Winter Olympics were to be held in America, in Squaw Valley, California, and CBS planned to make television history by giving the games their own time slot. In Squaw Valley the CBS Sports Olympics task force rented office space in the basement of the IBM building—a chance occurrence that would eventually transform all of football.

“That’s where I got my introduction to computers, which were new back then,” Schramm remembers. “IBM was doing all the scoreboards and the statistics. And they had computers. Massive computers. I started talking to them about what computers could do for a football team.”

He outlined the problem to the IBM Komputer Kids. Namely, it was getting harder and harder to tell which college players to draft. There was no system for evaluating talent, just old-fashioned hunches and meaningless statistics. The Komputer Kids said they would think about the problem and get back to him.

After the Olympics, Schramm returned to Dallas. He had invented the Olympics on TV, covering them just like a political convention, even using Walter Cronkite as his central anchor. Now he had to invent a football team. The Cowboys would be professional football’s first expansion team, and no one knew how to put one together, any more than Tex Schramm had known how to put the Olympics on TV. So he just made up the team as he went along.

The Cowboys worked out a deal to share office space with an automobile club. There weren’t any desks, so Tex and Tom and the boys sat on the floor of the car club, making calls and deals. It was an environment in which you could hear overlapping talk of quarterbacks and back-seat drivers, touchdown drives and vacation drives, retread tires and retread players. That is what most of the Cowboys’ original players were—retreads who were trying for a second chance after playing out careers with established teams.

Sitting on the floor of the car club, Tex Schramm got a call from his friends, the IBM Komputer Kids. They told him to get in touch with someone named Salam Qureishi, who was living in Palo Alto, California. They said that he could put anything in a computer, even a football team. In 1962 Schramm finally got around to calling Qureishi.

“Salam didn’t know a damn thing about football,” Schramm remembers.

“I only knew soccer,” Qureishi recalls. “I had never seen a football game.”

Nonetheless, Qureishi agreed to fly to Dallas to meet with the Cowboys. It was his first trip to Texas. And it was marred by a communication problem.

“I couldn’t understand Tex,” Qureishi says, “and he couldn’t understand me.”

Tex was unable to decipher the Indian singsong and vice versa.

“We will select the set of players,” Salam said one afternoon, “and then . . .”

But Tex didn’t hear “set”—he heard “sex.”

“Goddammit!” Tex exploded. “Don’t you know they’re just men? All men!”

Still, Qureishi eventually came to understand what the Cowboys needed: a computer program that could help identify and select the best college players coming up in the draft each year. He agreed to try to help the Cowboys.

He spent several months talking to coaches and scouts, asking them what it took to make a great football player. From those interviews he extracted a list of the five hundred phrases that came up most often. Phrases like “He would hate his mother if she was on the other side.”

Qureishi struggled to reduce this three-digit list to fewer than ten. For instance, he decided that the phrase about a player hating his mother just meant the player was competitive. So competitiveness went on the short list.

But it took a lot longer to make a short list than a long one. So while working to solve the programming problem, he had time to go to Cowboys’ games. At first he found the inside of a football stadium even more baffling than Tex found the inside of a computer. But he soon began to understand the game. And then to like it. And before long the Indian was a rabid Cowboys’ fan. Meanwhile, his research moved slowly forward—almost as slowly as the Cowboys moved the ball in those days.

“It was a long, painful process,” says Schramm. “It took us four years to find the elements that made successful football players. We finally got down to five things. One: character. Two: quickness and body control. Three: competitiveness. Four: mental alertness. Five: strength and explosion.”

But it wasn’t quite that easy.

Qureishi was afraid another communication gap might develop because one scout might mean one thing by, say, “competitiveness” while another might mean something slightly different. So he decided to give the scouts some help.

He didn’t just ask, “Is the player competitive?” Instead he asked if the following described the player: “He would hate his mother if she were on the other side.”

The scouts weren’t allowed to answer simply yes or no. They were asked to rate the player’s hatred of his mother on a scale from one to nine. The scale was lopsided, because three was average. The Cowboys cared more about correctly calibrating above-average than below-average players, so they allowed for more numbers in the upper range. If the player wouldn’t hate his mother at all, he got a one. If he would hate her an average amount, he got a three. But if he would really hate her enough to be a champion, he got an eight or nine.

Other sentences on the questionnaire included:

“He finally catches on after much repetition” (mental alertness).

“He would just as soon miss practice” (character).

“He rarely thinks of anyone but himself” (character).

“He doesn’t stop when the whistle blows” (competitiveness).

“He will break his neck to carry out his assignment” (competitiveness).

“He is quick as a cat” (quickness and body control).

“He is strong as a bull” (strength and explosion).

In 1964 the Cowboys were finally ready to put their computer program to the test for the first time. They fed into the computer all the players coming up for the NFL draft that year. The computer mulled over all those players—and how much they would hate their mothers if their mothers played for Green Bay—for a couple of hours. Computers worked slower in those days. And then the machine spat out a list of players ranked from 1 to 100. According to the computer, they were the 100 best prospects in the country. And as it turned out, 87 out of the 100 became pros. The computer was batting .870. That’s Hall of Fame stuff.

Here, in order, are the top fifteen players who headed that first list: Joe Namath, Dick Butkus, Gale Sayers, Fred Bilentnikoff, Mike Curtis, Steve DeLong, Clancy Williams, Roy Jefferson, Tucker Frederickson, Fred Brown, Ralph Neely, Dave Simmons, Jack Snow, Lawrence Elkins, Craig Morton. Eleven became starters.

Schramm began to worry not about the Packers or the Redskins but about IBM. Since Salam Qureishi worked for IBM, the giant company owned all the software that he developed—including the Cowboys’ new scouting program. What if IBM started selling it to other teams?

The Cowboys decided to start their own company. Qureishi resigned from IBM and went to work for the team’s brand-new subsidiary—something called Optimum Systems Incorporated (OSI). On his way out the IBM door, he gathered up all the football software, which the Cowboys had purchased from IBM.

With the computer helping, the Cowboys started to improve. They went from 11 losses and 1 tie in 1960 to 7 wins and 7 losses in 1965 to a 10–3–1 record in 1966, which earned them the right to play Vince Lombardi’s legendary Green Bay Packers in the NFL championship game. The Cowboys missed a tie by one yard before losing 34–27.

The next year the Cowboys played the Packers again, in the NFL championship game that would go down in football history as the Ice Bowl. The temperature in Green Bay was 13 degrees below zero with a wind chill factor of minus 41. In spite of the frigid weather that favored the northern team, Dallas led 17 to 14 as the game was coming to a frostbitten end. But with thirteen seconds left to play, the Packers scored on a quarterback sneak.

The following year, 1968, Qureishi helped the Cowboys become one of the first NFL teams—perhaps the first—to begin doing computer analyses of the unconscious tendencies of its opponents. He was able to tell the Cowboys, for instance, how often the Steelers were likely to run the ball on first down or how often the Giants were likely to try a quarterback sneak near the goal line. That opened the way to the making of modern-day game plans. The Cowboys often—in fact, usually—knew what the other team was going to do before it did.

In 1975, exactly a decade after it was unveiled, the Cowboys’ computer program for finding football talent did its all-time best job. In a single draft the Cowboys acquired Randy White, Bob Breunig, Herb Scott, Burt Lawless, Thomas Henderson, Pat Donovan, Randy Hughes, Mike Hegman, and Scott Laidlaw. In all, twelve rookies made the team.

Although the Cowboys had had a great draft, everyone assumed that it would take a while for the rookies to learn to play the game. So the Cowboys—who had failed to make the play-offs the year before—were considered a threat of the future but not of the present. But the Cowboys surprised themselves and everyone else by winning ten games and losing only four. Their success continued right into the play-offs, as they won the National Conference championship before losing to Pittsburgh in Super Bowl X, 21–17.

The Cowboys continued to be a successful football franchise. They played in Super Bowl XII, in which they defeated the Denver Broncos, 27–10. And they went to Super Bowl XIII, where they lost to the Pittsburgh Steelers, 35–31. But then in 1980 quarterback Roger Staubach retired and some weaknesses began to appear in the Cowboys’ football machinery. Some of those soft spots turned out to be in the software.

The Cowboys’ computer problems were the result of overreaching. Murchison had decided to try to turn his little computer company, OSI, into another IBM. He poured in capital and opened offices all over the U.S. And then he decided that Qureishi was not a good enough businessman to run the company he had helped found. Murchison wanted a big businessman to run his big computer company. The Cowboys fired the Indian in 1970.

“It was really bad,” Salam Qureishi remembers with a grimace. “Traumatic. I didn’t have any money. No income. No rich friends. I had to refinance my house. This was the roughest time of my life.”

Qureishi was essentially where the Cowboys had been back when he joined them: nowhere. So he decided to try to start a company from scratch the way the Cowboys had started a team from scratch. He borrowed $50,000 from friends. And he got a $10,000 loan from the Bank of America. He called his new company Sysorex International. Then he got in contact with Saudi Arabia.

“I knew Saudi Arabia would need what Tex had needed,” Qureishi recalls. “They were starting a country. We had been starting a football team. But they needed the same things.” He signed the Saudis as his first major client. It helped that his great-great-grandfather had come from that desert kingdom.

Qureishi, dumped because Murchison considered him an inferior businessman, now is in better financial shape than his ex-boss. Last year his business grossed $79 million. And it has a backlog of $200 million worth of work yet to be done. He paid back the money borrowed from his friends a hundred times over. And his Bank of America line of credit is $10 million. Meanwhile, Murchison’s computer company, which was to have been run so professionally, lost $50 million and went out of business. Many of his other investments had similar problems. Murchison has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. In 1984 he sold the Cowboys to a group headed by Bum Bright.

With Qureishi gone, the Cowboys’ ability to use the computer to identify talent gradually declined. Which has been a big part of what went wrong. “We had computer problems,” Schramm admits. “Our program deteriorated.”

The main problem was that no one kept the system up-to-date. It was designed to be overhauled at least once a year. But it was left to run year after year with no tune-up, and by the end of the seventies it was running the way a Chevy would if left to its own devices for so long.

The way this particular software system was supposed to be tuned up wasn’t by checking its spark plugs—it was by checking its scouts. Just as the scouts evaluated the players every year, the computer was supposed to go back later and evaluate the scouts to find who had correctly identified the boys who would stomp their own mothers into the ground. But no one had taken the trouble to do such a follow-up.

“A computer program is like a musical instrument,” says Qureishi. “You have to fine-tune it. The Cowboys didn’t tune theirs for years.”

After the great 1975 draft, the computer went sour. It came up with names of first-round choices like Aaron Kyle (1976), a defensive back of little note; Larry Bethea (1978), a defensive lineman whose best position was prone; Rod Hill (1982), a defensive back with a knack for turning ordinary plays into disasters; and Kevin Brooks (1985), a defensive lineman who has been invisible despite his 265 pounds. Three drafts were almost total washouts. Out of a dozen picks in 1978, only eleventh-rounder Dennis Thurman, a defensive back, made any contribution. The 1982 and 1983 drafts were so bad that by the start of the 1984 season, only two players from each class were left.

The problem wasn’t just who the Cowboys chose. It was who they didn’t choose. In 1983 the Cowboys could have picked both quarterback Dan Marino and wide receiver Mark Clayton. Instead they took defensive lineman Jim Jeffcoat and linebacker Mike Walter. Marino and Clayton led Miami to the Super Bowl in 1985. The Cowboys missed the play-offs.

The faulty computer explains why the Cowboys failed to draft Everson Walls and Michael Downs in 1981. They ignored the two defensive backs, choosing instead at that position the likes of Vince Skillings and Ken Miller, neither of whom has ever been heard from since, while both Walls and Downs have been named all-pro.

The problem was that the computer rated Walls’s quickness and body control at three or worse. And the software gave Downs an equally poor mark for competitiveness. But the computer knew only what the scouts told it. And the scouts somehow failed to mention that Walls led the nation in interceptions his senior year in college or that Downs had played his last year with an injured shoulder. So on draft day, the Cowboys overlooked Downs and Walls, even though both lived in Dallas and were right under their nose.

Fortunately for the Cowboys, every other team in the National Football League made the same mistake. Downs, who played at Rice University, went to the Houston Oilers’ offices to watch the draft on television. He stayed until the last name was selected. No one picked him.

Walls too had been forgotten. Although the Cowboys had not drafted Walls, they were interested in him. Interested enough to fly someone down to Grambling, Walls’s college, to meet with him after the draft. He was offered a free agent contract: $1500 to sign, $300 a week for every week he survived in training camp, and, finally, $30,000 a year if he made the team. Walls signed.

On the same day at about the same time, the Cowboys called Michael Downs. They met with him at the Marriott near the Astrodome. They talked for four or five hours, so Downs missed the plane that was supposed to take him to Pittsburgh to talk to the Steelers. Downs agreed to a contract similar to the one Walls had signed.

Though they had both grown up in Dallas, Michael Downs and Everson Walls met each other for the first time at the Cowboys’ rookie camp in Thousand Oaks, California. They were two of 25 defensive backs trying out for the team. At the most, three would survive. Three of the 25 made the team. Ron Fellows, Everson Walls, and Michael Downs.

Walls intercepted eleven passes his rookie year to set a Cowboys’ record and to lead the NFL. A rookie had never led the league outright before. He led the league in interceptions the next year. And last year he did it again. Everson Walls is the only player in NFL history to lead the league in interceptions three times. The Cowboys’ computer didn’t like him, but the record books are going to love him.

Michael Downs led the Dallas secondary in tackles for four years in a row. He has been the number one tackier on the Dallas team three times.

“Any front office that tries to create the illusion that they’re smart because their free agents made the team,” says Tex Schramm, “is just blowing smoke. If you had any inkling how good they were going to be, you would have been happy to draft them in an early round. We should have drafted Downs and Walls.”

At the end of the 1984 season, the Cowboys missed the play-offs for the first time in ten years. The Super Bowl—in which they might have played if they had not gotten rid of Qureishi—was staged at the Stanford Stadium in Palo Alto, California, Qureishi’s back yard.

Tex Schramm went to the Super Bowl as a mere spectator while his beaten team stayed home. Salam Qureishi heard that Tex was encamped at the Fairmont Hotel in nearby San Francisco, and decided to call him. Schramm asked Qureishi to come up and visit him in his suite. They had a good time reminiscing about the glory days.

“You ought to come back and help us,” Tex said—at last. This time Qureishi returned to the team as a free agent. Without cost. By then he was so rich he didn’t need the Cowboys’ money. He took them on as a charity case.

One of the first projects the Indian undertook was a reevaluation of the Cowboys’ scouts. He took the scores they had given all the players in recent drafts and matched them up against how well the players had actually done in the NFL. And, of course, two of the most glaring errors turned out to be Walls and Downs. The scouts who had given them threes or worse were given threes or worse themselves. Because Downs and Walls had turned out to be nines.

Qureishi is confident. “The Cowboys are going to have the best system,” he says, “because they have the most data.” But they haven’t been using their data the past few years. That is like keeping your best player on the bench.

Now all those data are being sent back into the game. The Cowboys’—and the Indian’s—new scouting program was unveiled at the college draft last spring. Qureishi had done his best to plug the holes in the Cowboys’ software the way Downs and Walls plug holes on the field.

“Things finally broke right for us,” says Tex Schramm. “We feel very happy about our draft.”

The Cowboys’ weekly newspaper ran a story that shouted: THE DRAFT THAT MIGHT BE DAZZLING. The story began, “It had been nine years since the Cowboys had made so much noise in the first round of the NFL draft, and as far as Schramm and the rest of the organization were concerned, it was long overdue.”

With his first draft behind him—the first of his second incarnation—Salam Qureishi is now turning his attention to the upcoming season and the future. He wants to get into the game. Send me in, coach, send me in.

Or rather, send in my computer.

He dreams of the day when the Cowboys will have a computer in the press box calling the plays. If not this season, maybe next. Or the next.

During his first incarnation, he made sure the Cowboys were one of the first teams to use its computer to prepare a game plan before the game. Now he wants his software to update the game plan during the game.

“Now if a game needs to be revised after the kickoff,” Qureishi points out, “the coach does it in his head. But the human mind blanks out with too many choices. That’s where the computer can help. Somebody is going to do it. Somebody is going to win a Super Bowl with it. I think it will be the Cowboys.”

Aaron Latham is a freelance writer who wrote “The Return of the Urban Cowboy,” Texas Monthly, November 1985.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas