On Saturday, that big, beloved, everyone’s-welcome gathering of bibliophiles, the Texas Book Festival, will kick off its twenty-sixth year, with more than 150 authors from around the nation set to speak in Austin and on Zoom. The hybrid event is mostly virtual again this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, though there are a few in-person events October 30 and 31 in downtown Austin. The massive lineup can be a little overwhelming to navigate, so we asked Texas Monthly staff members to recommend their favorite featured books by Texas authors or on Texas themes. You can also peruse the full schedule to see what else is on offer. Happy reading!

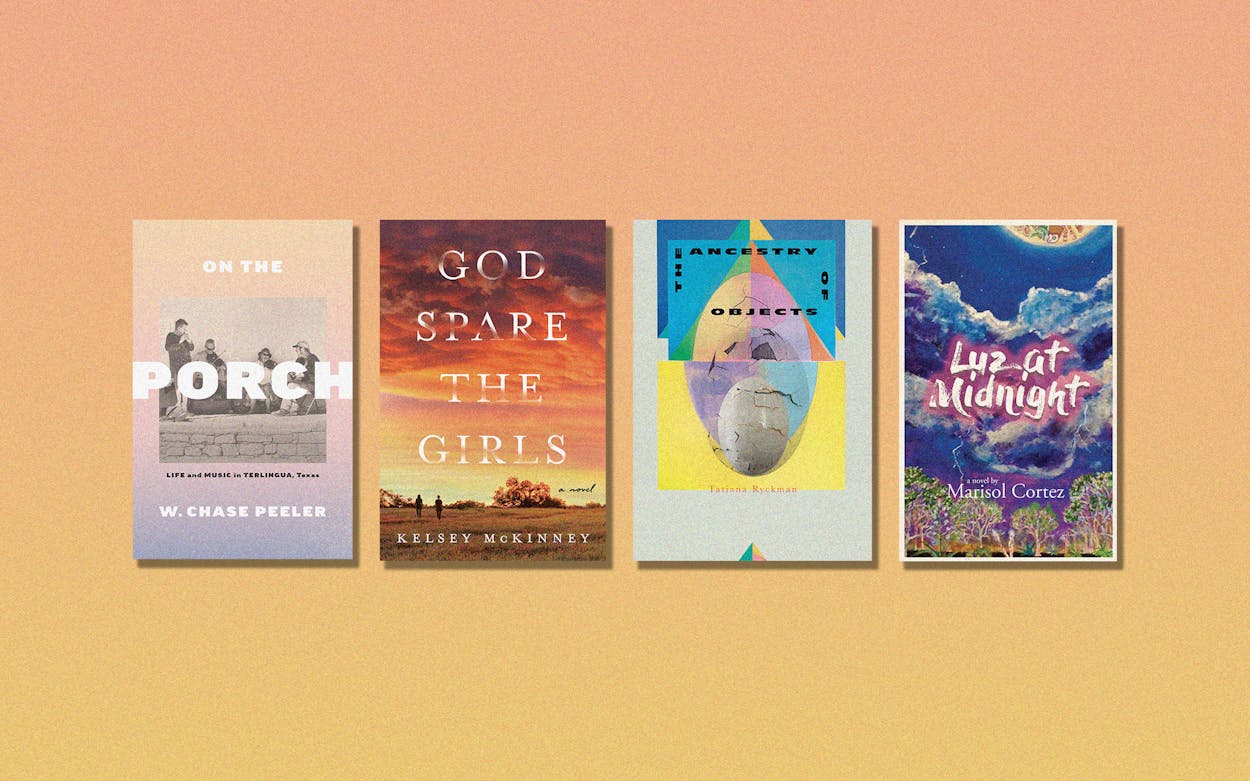

The Ancestry of Objects

By Tatiana Ryckman, Deep Vellum

The Ancestry of Objects is a novel of contradictions: it’s tender yet violent, spare yet lyrical, personal yet distant. The Austin-based author’s first novel, after a novella and two chapbooks, continues her exploration of the human desire to connect despite our inability to ever truly know another person.

The unnamed young woman who narrates the novel has lost her job and feels disconnected from the world around her. She comes home every night, alone, to the giant house she inherited from her intensely devout and judgmental grandparents. Left to her own thoughts, she spirals into depression and isolation; suicide seems like the only reasonable act in a life where she barely feels alive. She tries to fill this void through David, an older, married man, who elbows his way into an affair and her house. The novel loops through the protagonist’s memories, her affair, and her fantasies of a something better for herself. The narrator wants to believe that this intense relationship will save her, despite knowing that the affair, and maybe her future, will be destroyed by its own momentum. —Richard Z. Santos, freelance writer

American Made

By Farah Stockman, Random House

In the fall of 2016, the Indiana steel factory Rexnord announced it was relocating to the Texas border. One part of the operation would move to McAllen, the other to Monterrey, Mexico. The factory was a relic from the mid-century Midwest, a place where jobs were unionized and offered a piece of the American dream to an entire community. But that model had been dying for decades, and by 2016, another Rust Belt casualty shouldn’t have made much news at all. Except that then–president elect Donald Trump tweeted: “Rexnord of Indiana is moving to Mexico and rather viciously firing all of its 300 workers. This is happening all over our country. No more!” All this inspired the recently released American Made by New York Times journalist Farah Stockman.

Much of Stockman’s narrative tracks three laid-off employees after the Indiana factory closed. But some of the most illuminating moments in the book take place in Texas and Mexico. At one point, Rexnord ordered its Indiana factory workers to train their replacements at the new plants if they wanted to keep their severance, and Stockman details the anger, sabotage, and violence that followed. During one training trip, for example, a “Build the Wall” graffiti message appeared on a bathroom wall, and upon return from another, a trainer from Indiana explains to his bowling team that the machines he and his colleagues shipped to Texas began “unexpectedly” catching fire when used. American Made offers a unique look at what was happening on the ground at a time when the border had become an antagonist in Trump’s story that America, particularly blue-collar middle America, needed saving. —Paul Knight, associate editor

Aristotle and Dante Dive Into the Waters of the World

By Benjamin Alire Sáenz, Simon & Schuster

Benjamin Alire Sáenz’s much-lauded 2012 novel followed two teen boys coming of age in El Paso during the late eighties. Now Aristotle and Dante Dive Into the Waters of the World returns to the story of Aristotle and Dante, who are just as vivid as ever. While the first book explored how the teens fell in love with each other, the sequel zooms out to consider what exactly their budding relationship means for them and their working-class Mexican American families. The AIDS crisis is not-so-quietly approaching in the background too.

Sáenz’s book explodes with so much feeling and beautiful nuance that I savored every word on the page. He writes his characters with such sensitivity and tenderness. Ari and Dante are on the cusp of adulthood, attending their last year of high school with talk of college looming. They are coming to terms with who they are in a world that would rather they not exist, a world incredibly unjust and filled with harsh truths. Ari and Dante aren’t just characters you want to get behind and root for; they are characters you wish you had the privilege to know. —Neha Aziz, contributing writer

God Spare the Girls

By Kelsey McKinney, William Morrow

Kelsey McKinney’s propulsive debut novel is an unguarded, intimate reflection on faith and family. Set in the fictional North Texas town of Hope, the story follows two sisters and preacher’s daughters: Abigail is the older, beautiful sister who’s just weeks away from her wedding, and Caroline is a recent high school graduate who feels she’s often living in Abigail’s seemingly perfect shadow. When the two learn that their father had an affair with a member of their congregation, they decide to spend the summer at their grandmother’s ranch, where they struggle to process their feelings of betrayal.

As the weeks go on, the stay becomes an opportunity for the sisters to examine their fractured relationship with each other and with the religion they’ve known their whole lives. McKinney’s dive into evangelical Texas pulls from her own upbringing in North Texas and feels all the more authentic for it. In the Bible, women are often called upon to sacrifice themselves for the men in their lives. God Spare the Girls suggests that there’s a different path, with McKinney creating a thoughtful coming-of-age story in the process. —Cat Cardenas, associate editor

Nights When Nothing Happened

by Simon Han, Riverhead Books

In the first few pages of Simon Han’s debut novel, eleven-year-old Jack Cheng finds his younger sister, Annabel, outside in the middle of the night. She’s standing on a bridge near their home, swaying on her feet and hovering between wakefulness and sleep. Annabel doesn’t remember her sleepwalking incidents, and Jack, convinced of his role as her protector, doesn’t push her to remember, nor does he tell their parents, Liang and Patty. But her sleepwalking is a sign of the quiet, unspoken cracks that have been creeping through the Cheng family even before they relocated to Plano. In gentle, dreamy prose, Han switches among the perspectives of the family members. In one chapter, he captures Annabel’s childlike misunderstanding of the complexities between good and bad; in another, he reflects on the trauma and absences in Liang’s childhood and how this baggage still strains his relationships with his wife and son.

Han’s book is an exploration of the liminal space the Chengs occupy. As the four of them struggle to find their place in the affluent, often lonely Dallas suburb of Plano, as well as at home and with one another, they are still plagued by the questions that traveled with them from China. Twilight hours offer the family chances to either face their issues or wander further into misunderstanding. All too often, the conflicts grow, leading to moments of disaster that unfold with the slow-motion feel of a nightmare. But even as the cracks spread and threaten to separate the family, there’s still hope that the Chengs can come together and understand where and how they each belong. —Doyin Oyeniyi, assistant editor

On the Porch

By W. Chase Peeler, University of Texas Press

If you’ve ever ventured up the hill of the Terlingua Ghost Town, you’ve probably got a porch story. Perhaps you caught a sunset after a long day of hiking in Big Bend National Park. Maybe you cracked open a Lone Star, sweat slicking your back as you sheltered from the sun under the Terlingua Trading Company’s tin roof. Or maybe you parked yourself on one of the wooden benches and thumbed through the pages of a book. More than likely, while you soaked in the view of the Chisos Mountains and rested against that plastered adobe wall, someone was playing music.

On the Porch makes the case that Terlingua’s famous community porch is home to one of the most important and unique musical scenes in the state. Peeler first ventured to West Texas in 2013, in search of a place to study for his PhD dissertation in ethnomusicology. After first exploring Alpine and Marfa, he was surprised to find what he was looking for in this even more remote and sparsely populated pocket of southern Brewster County. There, on the porch that connects the Starlight Theatre Restaurant to the Trading Company, Peeler discovered a community of musicians unlike any other. The impromptu jam sessions that take place on the porch are akin to the monsoons that appear out of nowhere in this part of the Chihuahuan Desert. These sessions range from small gatherings to huge, hours-long, multi-instrumental affairs, but they always feel like the heart of this endearingly oddball, close-knit community.

Peeler became a regular presence on the porch, often playing music alongside the subjects of his research. It’s these relationships, and the respect he has for Terlinguans, that mercifully keep On the Porch from reading like an ethnomusicologist’s dissertation. Still, the book is rigorously researched: Peeler traces the porch jam tradition back to the ghost town’s early days, when only river guides and chiliheads were knocking about, and he contextualizes the role of Terlingua as a border town. As commercial tourism continues to grow in the region, there are some who worry that Terlingua’s musical culture could fade away. For those of us with our own porch stories, this book is a comforting testament that, whatever comes, these musicians and their music will always be remembered. —Christian Wallace, senior editor

Luz at Midnight

By Marisol Cortez, Flowersong Press

Early in Marisol Cortez’s kaleidoscopic debut novel, one of many departures from traditional narrative structure takes the form of a news story. In it, fictional journalist Joel Champlain lambasts the Electric Reliability Council of Texas for triggering not-so-rolling blackouts during an unanticipated February freeze. The article reads not unlike one that might have appeared in a publication such as Texas Monthly after the historic 2021 freeze—but Cortez actually penned her tale and Joel’s piece much earlier. What appears to be soothsaying in this work of climate fiction (and winner of the Texas Institute of Letters’ best first book award) instead results from its San Antonio–raised author’s detailed study of our state’s environmental inequities. She also draws on her own experience as a climate activist and community organizer.

Devotees of contemporary literature will delight in Cortez’s lyric experiments, and history buffs will appreciate her academic command of South Texas’s colonial past. But any reader with an interest in the longevity of our planet should take note of this touchstone for a surely burgeoning genre: though Luz at Midnight could not have been intended as an indictment how of those in power were surprised by our most recent February catastrophe, they’ve no excuse, the book makes clear, to be fooled again. —Alicia Maria Meier, assistant editor

The Souvenir Museum: Stories

By Elizabeth McCracken, Ecco

In one story in Elizabeth McCracken’s The Souvenir Museum, an American expat named Jenny Early heads back to England after a holiday to see her brother. On the daylong ferry ride, nestled in a private cabin, she’s adrift and alone. Early is a middle-aged actor who plays a villain on a children’s TV show but doesn’t want children. She has dual citizenship but neither, it seems, is for the country in which she lives. “All her life she’d felt foreign; landing abroad, she was relieved to assume it as an official diagnosis,” McCracken writes.

That craving to belong—the desire for home and family in their many, many forms—lies at the heart of these stories. Quests take the shape of trips to cities abroad, theme parks, museums, and, in one of the more haunting tales, a hotel in town for the saddest of staycations. And taking these journeys are the kinds of characters for which McCracken (Bowlaway, The Giant’s House) is known and much admired: flawed and lovable, quirky and lost. Longtime couple Jack and Sadie, who appear in several stories, probably best exemplify these traits; theirs is a love story born out of tragedy, restlessness, and puppets. We meet them first in the delightful opening story, “The Irish Wedding,” which first appeared in in the Atlantic and this summer was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award.

McCracken, who holds the James A. Michener Chair in Creative Writing at the University of Texas, sets two of these tales in our state. Two men, one much older, take their young son to Schlitterbahn (“Schlitterbomb,” the four-year-old calls it) in Galveston to ride the artificial lazy river in November. A grandmother-to-be scours the vintage shops in Austin for a specific kind of doll (one I remember too vividly from childhood) as grackles caw and glisten outside.

That these universal themes can be explored with such tender humor is a wondrous thing. Like the yearning mother Leonora who nibbles on her little ones, I wanted to devour The Souvenir Museum. How much can you safely love someone or, by proxy, something? It’s a question best considered with life-affirming humor and with McCracken as our guide. —Kathy Blackwell, executive editor