Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt, two of the godfathers of the Texas singer-songwriter tradition, continue to influence a younger generation of tunesmiths. And while Van Zandt has the cult status that comes to those who self-destruct before their time, his best friend, Guy Clark, had a long, storied career and a life full of complexity and nuance. Born in the West Texas town of Monahans and raised along the Gulf Coast in Rockport, Guy spent most of his adult years in Nashville, and died there in 2016 at age 74.

The new documentary Without Getting Killed or Caught makes the story of Guy Clark—and his friendship with Van Zandt—all the more interesting because it is told, for the most part, from the point of view of Guy’s wife and artistic partner, Susanna Clark. Academy Award–winning actress Sissy Spacek voices the narration, which draws heavily from Susanna’s diaries; she died in 2012.

The film premiered at South by Southwest this week, and is coproduced and codirected by Tamara Saviano and Paul Whitfield. Saviano and Bart Knaggs wrote the script, which is also based on Saviano’s award-winning 2016 biography, Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark. The filmmakers had access not only to Susanna’s diaries, but also to a cache of cassette tapes that she recorded of her own soliloquies and conversations with Guy and Townes, along with family photos, handwritten lyrics, and home video. Saviano had interviewed Guy extensively for the biography, and fellow musicians and friends also sat for interviews, including Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, Vince Gill, Verlon Thompson, and Terry and Jo Harvey Allen.

With Susanna at the center of what is basically one long, extended conversation, the documentary takes the radical approach of showing how the story of Guy is in many ways just as much a story of her. The interviewees clearly respect Susanna’s varied gifts. A talented poet and painter, she illustrated several album covers, including Willie Nelson’s Stardust. Susanna was also a songwriter; in addition to her own compositions, she cowrote one song with Townes and six with Guy. That’s not to mention her attitude. “She was as no BS as Guy was,” says Rodney Crowell, while Steve Earle notes, “We learned to write songs from Guy and Townes, but we learned how to carry ourselves as artists from Susanna.” And from Guy himself, “[She was so] talented … she could write. Good lord, what a beautiful woman. Smart … but she wouldn’t clean her [paint] brushes!”

A verse from “Stuff That Works,” cowritten by Guy Clark and Rodney Crowell, is an especially nice fit in the narrative: “I got a woman I love, she’s crazy and paints like God/She’s got a playground sense of justice, she won’t take odds.” We hear Guy riff on the photo of Susanna that graces the cover of My Favorite Picture of You, his final studio album, which won a Grammy Award in 2014. The portrait shows her with arms crossed, staring into the lens with a serious, don’t-mess-with-me stare. “[That] look … I’ve seen it a thousand times,” Guy says, with the affectionate mix of love and frustration that anyone who’s been in a long-term relationship will understand.

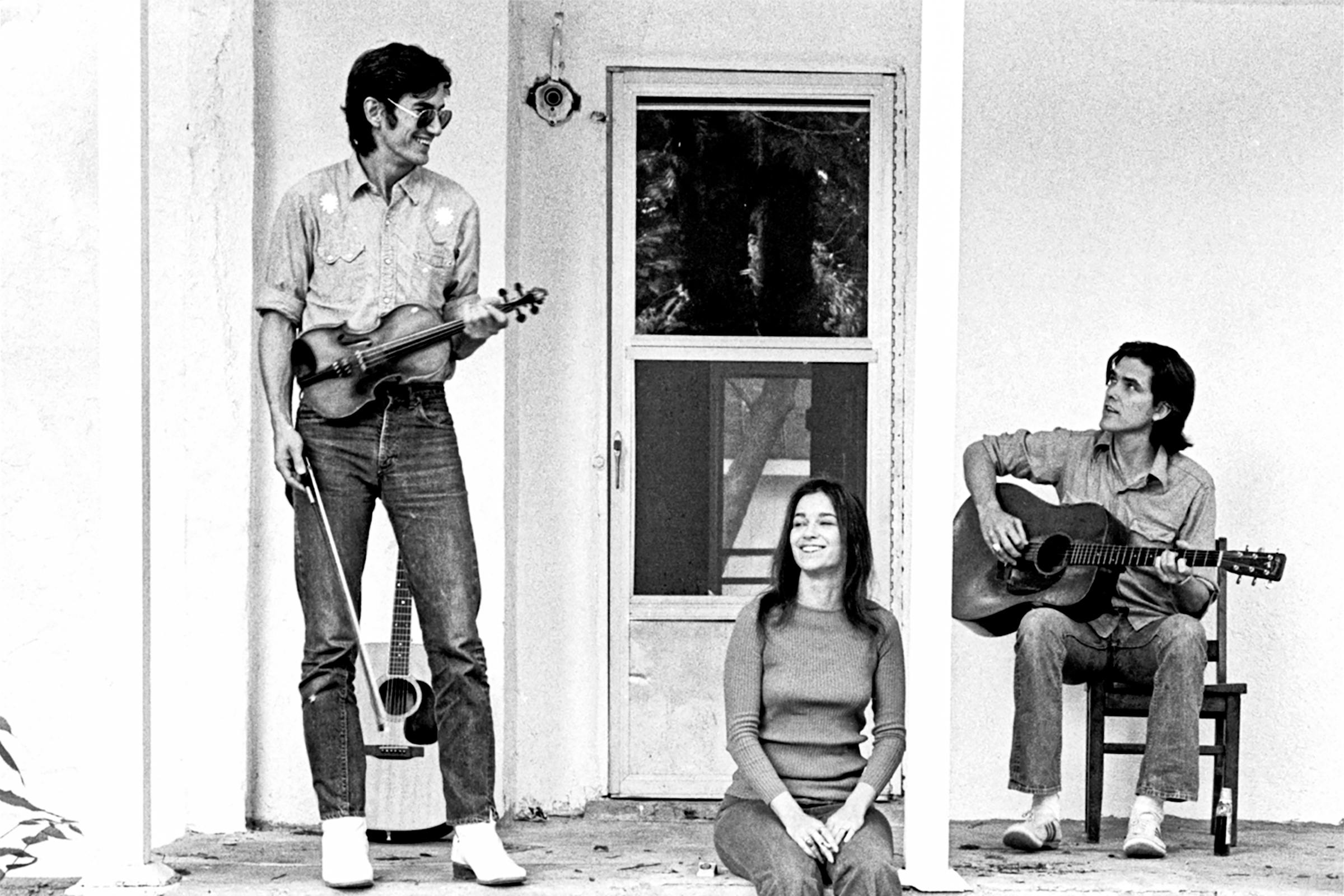

While Guy and Susanna’s partnership is at the center of this film, Without Getting Killed or Caught also explores the close-knit creative trio they were part of alongside Townes Van Zandt.

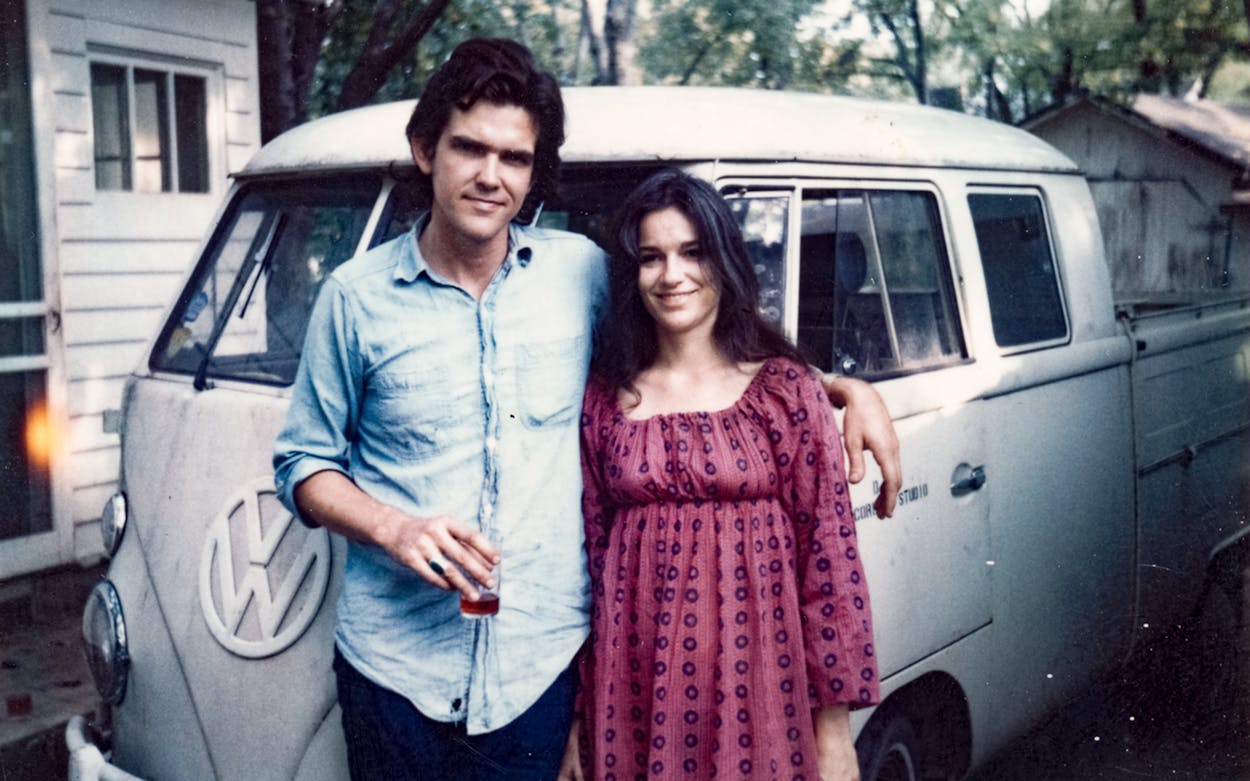

Susanna first met Guy and Townes in Oklahoma City in 1968, when Guy was dating her sister Bunny Talley. Townes later served as best man when Guy and Susanna exchanged vows in January 1972 in Nashville, and the three even lived together for several months. Susanna explained it this way: “Guy and I were married. Guy and Townes were best friends, but Townes and I were soulmates.” Through the years, Townes regularly called her—always at their appointed time, 8:30 in the morning. Everyone agrees that the relationship was unique and, on occasion, intimate. Van Zandt’s death in 1997 proved to be devastating for Susanna, and she was never the same afterward. “Life without Susanna began when Townes died,” Rodney Crowell says onscreen.

The documentary follows Guy Clark’s career with some surprises mixed in among the familiar territory, with the cast offering insights along the way. His music defied categorization, blending folk, country, and bluegrass, and leaving record-label executives puzzled as to how to market him. That didn’t matter to Guy, who wasn’t particularly interested in fame. “Guy wasn’t in the business of harvesting stardom,” Crowell says. “He was in the business of harvesting art and poetry.” Or as Clark himself wryly quipped, “[I’m] cursed with artistic integrity.”

As with any good music documentary, much of the pleasure of this film comes simply from listening. The movie opens with Guy singing “L.A. Freeway” as a VW bus with California plates is seen heading toward Nashville. And the soundtrack is replete with other Clark standards: “She Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” “Let Him Roll,” Desperadoes Waiting for a Train,” “Rita Ballou,” “South Coast of Texas,” “The Randall Knife,” “Dublin Blues,” “Stuff That Works,” and “My Favorite Picture of You.” Saviano and Whitfield have selected clips from various live performances to further emphasize his commanding stage presence.

The final edit will, no doubt, delight longtime fans, while serving as a fitting introduction for newcomers to the Clark saga. And it deserves to be ranked with Margaret Brown’s seminal Be There to Love Me: A Film About Townes Van Zandt (2004) and James Szalapski’s cinema verité Heartworn Highways (1981), which captures youthful Guy, Townes, and Susanna in 1975, along with an even younger Rodney Crowell and Steve Earle.

As the narrative winds to its conclusion, installation artist, sculptor, and singer-songwriter Terry Allen talks about Clark’s request—a joke at first, then a reality—that his ashes be incorporated into one of Allen’s sculptures. In his final years, as his rapidly failing health forced him to reckon with his own mortality, Guy became fascinated with a Dust Bowl–era crow’s nest made out of barbed wire at the American Windmill Museum in Lubbock; he was even working on a song about the crows that he asked Rodney Crowell to finish (“Caw Caw Blues” is included on Crowell’s 2019 album, Texas).

“I remember he had a line about ‘They [the crows] were so black you could only see them at night,’” says Allen. “He was really talking about his own vulnerability at that time.” Allen then chose to sculpt and cast a bronze crow that contained his friend’s ashes. In the final scene of the film, the camera finds the finished statue resting on a table on Allen’s patio in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The crow seems to survey the landscape and take it all in. The only sounds we hear are the wind and the birds. The closing credits roll as Rodney Crowell sings “Heckle and Jeckle built a barbed wire nest / In a windmill derrick way out west … Caw Caw Blues, Caw Caw Blues.”

In 2020, Terry Allen donated the crow statue, now officially titled Caw Caw Blues, to the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University. The crow will be stationed near the entrance of the Wittliff Gallery in the university’s Alkek Library. Guy Clark has returned to the Lone Star State yet again, and this time he is here to stay.