A few miles west of where Houston’s highway sprawl fades from a parade of superstores into the steamy low countryside, a slight rise in U.S. 290 reveals a surprise: six perfect circles of close-cropped grass clustered on the prairie like petals on an enormous flower. Here, spread across 86 acres and just an hour’s drive from the heart of the city, the nation’s largest and most advanced collection of cricket grounds attracts hundreds of athletes every week from around the Houston area—and often from around the country.

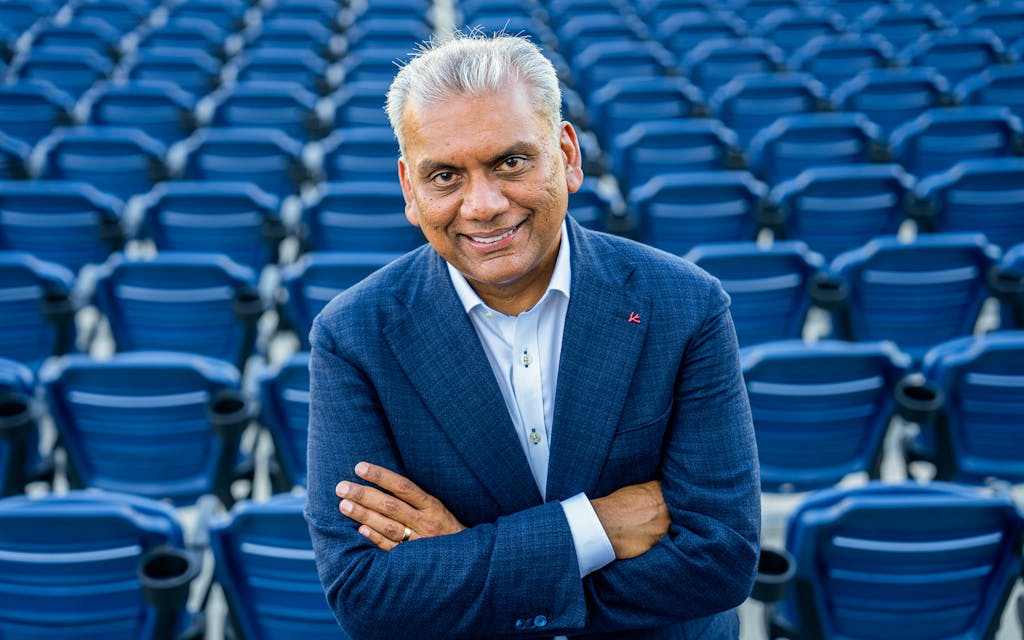

This is the Prairie View Cricket Complex, and on a recent Sunday, as the national junior cricket championships unfolded before him, the Texan who envisioned this place and paid to build it took a seat on the metal bleachers to explain how it all happened, and what it signified. Sporting mirrored aviator sunglasses, a body-hugging T-shirt, and a carefully groomed field of salt-and-pepper stubble, Tanweer Ahmed quickly rolled the clock back to 1988, when he arrived in this country from Pakistan at age twenty, with $23 to his name.

He’d come for the American dream but quickly realized there would be no handouts, he said. He took two jobs, one at a gas station and one at a Jack in the Box, and started learning English by watching American movies, especially The Terminator. He’d been working since he was ten years old back in Pakistan, selling vegetables from his family’s farm outside the city of Sialkot, and he’d managed to pay for two years of college there as well—so he was quick to impress his American bosses. By 1991 KFC hired Ahmed as a store manager. He was on his way.

Today Ahmed, who lives in Houston, is one of the country’s largest fast-food franchise owners, with some four hundred KFC, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell restaurants in four states. His passion, though, is cricket. And beginning about five years ago, he decided it was time to start paying his success forward—by investing heavily in the sport in Texas and building the Prairie View complex. “The whole idea that I have is, I came to this country, this country blessed me, and now I owe something back,” he told me.

Cricket is the world’s second-most-popular sport, Ahmed explained, with more than a billion fans, the vast majority of them from the Indian subcontinent. Meanwhile, Indians, Pakistanis, and other South Asians today make up the fastest-growing demographic group in the U.S., at 5.4 million strong. And Texas has the country’s second-largest South Asian population, just behind California and ahead of New York, New Jersey, and Illinois. The math wasn’t hard: cricket was wildly underrepresented in the nation’s landscape of recreational opportunities.

Ahmed’s complex in Prairie View is one of many in the U.S.—with a crucial but subtle difference. At the center of each circular field, under a rectangle of even finer turf, lies a layer of clay soil that has been rolled so flat and hard that a leather cricket ball will bounce as if on concrete—a differentiator from baseball because of how many variables this feature introduces to pitching and batting. Most of the other U.S. cricket grounds use artificial grass for the infield playing surface, a cost-saving measure that purists say just doesn’t offer the same quality of bounce. In Plano, Russell Creek Park claims to be the only park in the country with seven cricket fields, all with synthetic infields. Ahmed, ever the entrepreneur, saw an opportunity to level up.

He wasn’t the only Texas businessman to see an angle. Around the time Ahmed was starting his management career with KFC, another South Asian immigrant, Anurag Jain, was beginning business school at the University of Michigan. Jain, who moved to the U.S. from Chennai, India, when he was in his early twenties, had grown up as a talented but raw cricketer who dreamed of playing professionally but who instead followed his father’s advice to pursue a more sensible career.

As Jain earned an MBA and embarked upon a career as an entrepreneur in health-care IT, he fed his cricket addiction by getting up at three or four in the morning to watch live matches broadcast from the other side of the planet—a ritual shared by many of his South Asian peers in this country. “We’ve got this strange dual life where we’ve tried to keep in touch with cricket while we live our normal lives in the U.S.,” he told me. He longed to find his way back to the sport in a bigger way and loved the idea of building up American cricket—”but for the longest time it was just too much money.”

Then Plano-based Perot Systems, an IT firm created by Ross Perot and his son, bought one of Jain’s first companies, Vision Healthsource, in 2003. Jain moved to the Dallas area, and he and Ross Perot Jr. began investing in other projects together. That was right as the sport of cricket itself began to change. Traditionally, a single match lasted five days, and even then it often didn’t result in a winner. A one-day format emerged in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until 2003 that another change allowed matches to be completed in three and a half hours—a format known as T20 cricket. The Indian Premier League debuted in 2008, and it quickly turned T20 matches into the kind of live television Western audiences are used to, complete with cheerleaders and Bollywood celebrity appearances. Seemingly overnight, a gentleman’s pursuit turned into a high-scoring bat-and-ball sport that made baseball look sleepy. “And that,” said Jain, “became the future of the sport.”

By the late 2010s, he and Ross Jr. had set up a venture capital firm, Perot Jain, and built a strong professional network in Silicon Valley. That’s where Jain found his opportunity: a start-up called Major League Cricket. Ahmed, as it turned out, discovered the same opportunity at about the same time.

As Ahmed and Jain were starting to dream of a thriving cricket culture in Texas, two tech entrepreneurs in the Bay Area, Sameer Mehta and Vijay Srinivasan, were looking at the same trends and dreaming of a media and sports empire. They’d left their start-up jobs in the early aughts and launched a pay-TV channel dedicated to cricket. Willow TV, named for the type of wood in a cricket bat, didn’t become an immediate household name in the U.S., but it didn’t need to: by aggregating matches from around the world for Western audiences, the network turned the U.S. into the world’s fourth-largest cricket media market.

The number of talented cricketers emerging in India to play in the IPL had meanwhile started to outpace the number of opportunities in the league, and players began looking for jobs in other cricket-loving areas—Australia, the Caribbean, England, South Africa. That’s when Mehta and Srinivasan hit on the idea to start a professional league in the U.S., and Major League Cricket was born. They’d already proven a fan base existed here, so why not bring those supporters an original product? And if Major League Soccer could set its sights on eventually competing for attention with professional baseball and basketball, why not cricket?

The idea isn’t as far-fetched as it might sound. Cricket has a long history in the U.S. There’s even evidence of George Washington’s troops playing “wickets” at Valley Forge in 1778. That makes sense, because the sport spread with British imperialism as a way to inculcate British values in colonial subjects. Cricket faded in the U.S. in the late 1800s as baseball took hold, largely because the American game didn’t require the same kind of perfectly flattened and groomed turf. But now that so many new Americans come from India and other parts of the former British empire, there’s a natural symmetry to cricket’s contemporary return.

As word of Mehta and Srinivasan’s plan spread through the loose network of U.S.-based South Asian business leaders, it quickly found its way to Jain and Ahmed, both of whom signed on as investors in a $44 million round of funding by the league. Also piling money into MLC from its earliest days were Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, Adobe Chairman and CEO Shantanu Narayan, and the principals of major venture-capital firms such as Madrona Venture Group and Rocketship VC.

It was a powerful group of people, all of whom brought their own considerable egos and financial ambitions, but all of whom also shared an underlying passion for the game that ran much deeper than the dollars at stake. “It’s sort of a badge of honor,” the league’s head of marketing, Tom Dunmore, told me. “American cricket is fortunate that many people who love it are immigrants who have come here and done well, and they can afford to invest in the sport or build a cricket pitch.” It’s different from soccer, he pointed out, because you can’t just whip up a game on any old playing surface. “But there’s a lot of community benefit that comes with setting up and maintaining cricket infrastructure.”

Even with all of their competing interests, it didn’t take long for the league’s backers to zero in on Texas as MLC’s early center of gravity. Several of the most powerful investors were here—not just Ahmed and Jain, but also Ross Perot Jr., who signed on alongside his business partner and has a long history of doing business in India. There was also Ahmed’s complex in Prairie View, which the league decided to use as a training ground and a site for junior tournaments and other player-development projects. And there was the fact that moguls and teams from Seattle and San Francisco could fly to Texas for matches just as easily as those from New York and Washington, D.C.

But perhaps most important, when the league set out to find a stadium to host its first matches, it found the perfect site in Grand Prairie, the Dallas suburb sandwiched between Irving and Arlington, just south of Dallas–Fort Worth International Airport. A former independent league baseball stadium built in 2008 for the now-defunct Texas AirHogs, the grounds would require a substantial redesign and renovation, but that would cost half as much as constructing a new stadium. And the league quickly found that building in Texas is a lot easier than in, say, California. “The fact is, we get stuff done in Texas, and the regulators are helpful,” Jain said. “You can come here and within a year or two have all the permitting done and a stadium up and running. It’s so much easier to do business here, and you don’t realize that until you go other places.”

On an early June morning in Grand Prairie, just over a month before the opening day of MLC’s inaugural season, construction workers were preparing to pour concrete to form one of the last remaining sections of the stadium risers to be built, and another crew was repainting the VIP suites upstairs. (The season, which began July 13, will run as a two-week-long tournament, featuring eighteen total matches between six teams.) Out on the field, the central rectangular area—the pitch—was roped off to protect its turf, while sprinklers doused the sand covering the rest of the circular playing field. A shipment of sod would be showing up that afternoon, to be laid down on an eleven-inch-deep bed of highly specific sandy soil approved by the United States Golf Association, the nation’s reigning authority on sand for turf sports.

Dave Agnew, a tousle-haired Aussie who has built cricket pitches all over the world and whom MLC brought to Dallas to work full-time getting this one just right, oversaw the field work, while William Swann, another tall Australian, managed the entire $20 million construction project. Their jobs weren’t easy. Baseball and cricket share some obvious attributes—pitchers, batters, fielders—but the playing fields and surrounding structures are not easily transferable between the two sports. The entire stadium, save for the suites, had to be gutted to make room for the circular field. Where the baseball field had been two and a half acres, the new cricket surface is four. Even so, MLC managed to increase the stadium capacity from about five thousand to seven thousand fans.

On top of that, Russia invaded Ukraine a few weeks before work began last spring, and the resulting supply chain snarls slowed down plans from day one. A backup generator the crew ordered last summer had a 54-week lead time, meaning it should arrive just in time for the season. Meanwhile, a rainy spring this year has interrupted work days over and over. When all that expensive soil and sand turns to mud, concrete trucks can’t pass through the pitch to work on the stands for at least a few days.

But for all the potential construction snags, one of Swann’s biggest concerns was the relative paucity of luxury amenities and suites. “We have thirteen suites and two clubrooms, and once you go through the list of high–net worth individuals who will be coming, you quickly start to run out of suite space,” he said. Earlier this year, several teams from the Indian Premier League invested in MLC teams, and that introduced a whole new layer of wealth and influence to the mix. The New York MLC team, for instance, became MI New York, a reference to the Mumbai Indians, owned by the Indian oil conglomerate Reliance Industries, whose chairman, Mukesh Ambani, is Asia’s richest man and the world’s richest sports-team owner. The Dallas-based Texas Super Kings became affiliated with the Chennai Super Kings, a club owned by a powerful Indian cement company.

Aside from upgrading the furniture in the suites and updating the concessions to include samosas and roti wraps alongside hot dogs, there’s not much more Swann’s crew can do to accommodate the league’s VIPs. But the dilemma about adequate luxury space speaks to the size of the opportunity in U.S. cricket.

One of the most important areas of the stadium is an expanse of concrete on the concourse level that’s big enough to host sponsor activations—to show off a new car model, say. “You’ve got to pay the bills,” as Swann put it. The more built-in potential there is for sponsors, the more they’ll pay, the more the league can grow, and so on. The six teams competing this year (representing Los Angeles; New York; San Francisco; Seattle; Washington, D.C.; and Texas) will grow to eight at some point in the next few years, if all goes according to plan, with further goals of expansion down the line. Each franchise will ultimately want a home stadium. And once there are world-class cricket stadiums around the country, they can host international events. Already the 2024 T20 World Cup plans to hold some matches in Grand Prairie.

As Swann and Agnew talked field specs and growth opportunities, a young Sri Lankan woman who works in digital marketing for the league, Zayanya de Alwis, listened quietly and then interjected that the opportunity goes beyond cricket’s existing fan base. “We want the South Asian community to come out, but we also want to let American kids know about it,” she said. Where she lives, in the Bay Area, the younger generation is already “cricket mad,” she said, especially in the Silicon Valley corridor between San Francisco and San Jose, where practically every high school has a competitive cricket club. Here in North Texas, some public schools in Frisco have similar groups, but others aren’t there yet. As MLC builds out its infrastructure in Texas, de Alwis has started reaching out to more schools and groups such as the Grand Prairie ISD phys ed teachers and the Grand Prairie Police Department, which puts on sports-focused summer camps.

Youth cricket may represent the future of American cricket, but the sport also needs adult fans now. One of the boldest projects on that front is taking shape about thirty miles north of the stadium, at Grandscape, a sprawling shopping mall and entertainment complex in the Denton County suburb the Colony. Here, just across a sidewalk from an indoor go-karting palace and something called the Puttery (“immersive, adults-only mini golf, craft cocktails, and upscale eats”), the first American location of Sixes Social Cricket, a new kind of sports bar, opened last month.

Inside, a row of electric-orange batting cages and scoreboards flanks a bar and restaurant area. Diners choose from sandwiches such as the Delhi Smasher (chicken with Indian seasonings) and the Sri Lankan Fielder (a veggie burger) while taking turns batting against virtual bowlers (pitchers) who hurl balls from large video screens at the far end of each fenced-in cage. Purple, green, orange, and blue stripes cover every surface of the room, in varying sizes and orientations. “We were going for that Paul Smith look,” the company’s cofounder and CEO, Calum Mackinnon, told me. “But also, we want people to walk in here and go, ‘What’s going on?’ If people don’t do that, we haven’t done a good enough job.”

One afternoon a couple weeks before the grand opening, Mackinnon, who previously ran a small chain of Scottish restaurants in the United Kingdom, took a break from final preparations to demonstrate his bar’s game technology. As a Scotsman, he hadn’t grown up with cricket (“It’s really more of an English thing,” he said), but he’d found himself drawn to the growing trend of so-called social-entertainment restaurants—places like the Puttery and Topgolf. After a concept for a whiskey bar with virtual hunting failed to take off because of COVID-19 disruptions, he turned his attention to cricket. “And as soon as we opened this in the UK, the feedback was overwhelming,” Mackinnon said. “We got more than four hundred franchise requests from all over the world in just a year and a half.” With eight locations in the UK up and running and with MLC starting up here, opening in the Dallas suburbs felt like a natural next step.

In cricket, the term “six” is the equivalent of a home run in baseball, and the batting cages at Sixes register where players hit the ball and assign scores accordingly. After a couple of whiffs, Mackinnon hit a six. “It’s not like baseball, where the ball’s flying at you a hundred miles an hour,” he said. “People can pick this up relatively quickly, and it’s all about getting points, getting people competitive.” Typically, he said, people get better with a few drinks in them. “My sweet spot is four or five pints. Then it goes remarkably downhill quite fast.”

He’s in close contact with MLC, and he said a couple of his batting cages would eventually end up in the Grand Prairie stadium as amenities for fans and marketing vehicles for the restaurant. But ultimately, “we don’t really market to the cricketers,” he said. “The cricketers will find us. There’s such a huge South Asian population around here, they’ll be excited and bring their noncricketing friends, and that will create positive momentum.” He’d seen it work already in the UK: “Eighty percent of the people that come to Sixes there have never played cricket before.”

Back at Tanweer Ahmed’s Prairie View Cricket Complex, out on Field 5, a sixteen-year-old player named Aarin Nadkarni sprinted from the far edge of the round field toward the center, where a batter stood at one end of a rectangular strip in front of the wicket, a formation of three sticks in the ground with two smaller sticks balanced across the top of them. As he reached the far end of the rectangle, Nadkarni windmilled his outstretched right arm overhead in a violently fast circle and released a leather ball, smaller and harder than a baseball. His whole body pitched forward with his momentum, a mane of wavy black hair bouncing around the edges of his yellow ball cap as he braked to a stop and the batter took a swing.

It was the penultimate game of a weekend-long tournament that’s part of the MLC under-seventeen cricket championships, and Aarin’s Houston-based MSCA Hurricanes were facing a squad from New Jersey. In T20 cricket, each team gets one turn at bat and another fielding. The Houston boys batted the first half of this match, scoring a respectable 164 runs, and now it was time to try to hold their opponents to fewer. Aarin, his coach told me from the sideline, is one of the country’s top young fast bowlers (essentially a pitcher with a mean fastball), and the strategy today was to bowl aggressively from the outset to neutralize the opposing team’s top two or three batters early.

The Houston coach, Sushil Nadkarni, is also Aarin’s dad. Like Jain and Ahmed, he came to this country as a young man, in his case from the Indian city of Pune in 1999, to pursue a master’s degree at Texas A&M–Kingsville. After grad school, Nadkarni began a career doing environmental-impact management for a multinational consulting firm with clients in the oil and gas industry. He also played competitive cricket. He’d been an elite youth player in India, even making the under-nineteen national team, and he quickly came to dominate the American cricket scene, becoming captain of Team USA and the best batter in the sport’s domestic history, with a practically unfathomable batting average of 51.3 percent. “The next highest was thirty-six,” he offered proudly.

Between bites of a taco for lunch in the bleachers, Nadkarni kept one eye on his team as he described how he started Master Strokes Cricket America, the first training academy of its kind in the Houston area, in a Katy strip mall in 2015. Today there are dozens of academies around Texas’s biggest cities, Nadkarni said—“one on every corner” in some areas. At MSCA, players learn batting and bowling skills and work on physical conditioning.

It’s the kind of training Nadkarni received in India, and it wasn’t available in this country until recently. On the field, the quality of cricket the boys play here isn’t quite up to the level of equivalent Indian or Pakistani teams, Nadkarni said, but it’s not far off. The difference is not the amount of raw talent here. “It’s the amount of cricket played,” he explained. “In India they’re playing three or four games a week.” It’s just a part of the culture there, in the way that kids play basketball or soccer here.

For now, as cricket remains a niche sport, playing seriously is an expensive proposition for young athletes. Many of the players come from white-collar families. It costs a thousand dollars to attend a good academy for a year, plus another thousand or two in various tournament fees. Then there’s expensive gear to buy and the cost of family trips for travel tournaments. “It’s easily twenty or twenty-five thousand dollars a year,” Nadkarni said—and unlike many other sports, that doesn’t currently come with the potential payoff of a college scholarship.

For Aarin Nadkarni, who grew up in a cricket household and watches all the cricket he can on Willow, the start of Major League Cricket holds up the possibility that he could have a bright future in the sport in this country—without having to moonlight, as his dad always did. In addition to youth competitions, MLC also runs a set of minor league teams, and both efforts aim specifically to develop the next generation of pros. While most of the major league players will be foreign nationals, franchises are required to maintain a minimum number of U.S. residents on their rosters, with plans to also maintain dedicated slots for younger players. Aarin hopes to be one of the first to enter that pipeline, though he’s planning to go to college as a backstop.

A second-generation immigrant in suburban Houston, Aarin is every bit as Texan as he is Indian. He follows football and basketball, but rather than getting pulled away from cricket toward those American pastimes, he has found space for all three in his life, and he sees a similar blending of cultures happening among his peers as cricket becomes increasingly baked into life in the States. “Almost all of our parents are immigrants, and we consider ourselves American,” he said. “But we think cricket is a good sport. It’s just a part of me.”

Aarin’s team lost the game that afternoon in Prairie View—he successfully bowled out two of the most dangerous New Jersey batsmen, but the third got the better of him. “He was the highest run scorer in the tournament and ended up taking the match away from us,” Aarin said later. The Hurricanes lost again the next day playing a team from North Carolina. The Houston boys entered the weekend ranked first of the thirty teams playing and, despite the losses, ended up still in the top four based on the tournament’s scoring system. It was the first of three tournaments that will eventually crown the MLC youth national champions in December.

Ahmed believes playing cricket teaches important values. “You can’t have a gentleman’s game without patience and discipline,” he said. And self-reliance. “Whereas you can hide yourself on a soccer team, you cannot hide here. You will be exposed in a second.” (It also appears that knocking rival sports as lesser pursuits is one of fandom’s universal values.) He sees parallels between success on the pitch and his own bootstrapped fortune, and he worries that immigrant new Texans today lack the same drive. “The people who are coming over here now are different,” he said. “They believe you can pluck dollars off a tree and get rich overnight.”

It’s a belief that only furthers his commitment to building out a cricket culture in Houston. And, lately, Ahmed has considered entering politics. Ever since he met former U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo at an event last year, he’s begun spending time in Palm Beach, Florida, with Republican lawmakers and former Trump administration officials, whom he says are recruiting him to run for Congress.

Regardless of that project, he’s working to make sure one of MLC’s first expansion teams lands in Houston, within the next five years. He’d originally wanted the Texas team there, close to his cricket complex, but the stadium opportunity in Grand Prairie—and Jain’s influence in Dallas and slightly larger ownership stake in the league—proved insurmountable. Between MLC, hosting next year’s T20 World Cup, and cricket becoming an Olympic sport in 2028, when the games will be held in Los Angeles, Ahmed believes, the U.S. will emerge as one of the premier cricket nations in the world.

After the Hurricanes’ tournament game back in June ended and players started trickling away, Ahmed stopped one of them to chat—a fifteen-year-old named Danyal Bhagani, whose eighteen-year-old brother, Rayaan, plays on the Houston minor league team and is one of the best hopes for a local breakout cricketer, along with Aarin Nadkarni.

“You see that?” Ahmed said to me after hearing how many runs the boy scored and wishing him good luck and hard work for the next day. “They moved here, he and his brother, two years ago from L.A. because of this.” He gestured around at the dream fields he had built, at the long stretch of highway frontage that functions as free advertising. Players were moving here to train at Sushil’s academy and be close to the country’s best cricket complex. Teams were flying in from the coasts to compete against them. “We can do a lot with this,” he said.

A few weeks later, the temperature was 103 in Grand Prairie when Ross Perot Jr. bowled the ceremonial first ball of the first match of Major League Cricket. Outside the sold-out stadium, hundreds of frustrated fans stood in line for more than an hour to pass through a security bottleneck, and a police officer hurried to help someone who’d fainted in the heat.

Inside, past the orange Sixes batting cage and a promo tent from Royal brand rice, league reps handed out giant yellow-and-blue Texas Super Kings flags. By a little after 8 p.m., the lines had finally cleared, and thousands of fans blew yellow plastic whistles in a nod to a Chennai game tradition. After a Texas player hit a six, a roar went up and the flags started to wave in the stands. A pair of drummers beat their way through the concourse. As the crowd settled down, the sound system played “Deep in the Heart of Texas.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Business

- Grand Prairie