How do you play a Texan? On its face, it’s a ridiculous question. There are some 30 million Texans scattered across disparate regions the size of some European countries, each with their own ideas about what constitutes a Texan. The rancher in Goliad certainly wouldn’t let some boho Austinite define it. Yet “Texan” remains one of those archetypes, like “New Yorker” or “nerd,” that crops up repeatedly in our popular fictions. I guarantee that no actor has ever walked into an audition to find “Delawarean” on the call sheet.

People have been playing Texans on-screen since the advent of film—and they’ve been catching flak about it for nearly as long. We may not all agree on what constitutes a real Texan, after all, but we can damn sure spot a fake. Still, such conviction is a tad ironic, considering that being Texan involves a certain amount of playing Texan ourselves. We like to believe in the idea of Texanness as something inborn. But the truth is, we’ve internalized an awful lot from those fictional depictions. As we get further afield from the days of Sam Houston and Gene Autry, they’ve colored how we dress, talk, and carry ourselves. Texans tend to measure themselves against those Wild West myths, creating a sort of ouroboros identity that’s built partly on our lived experiences and partly on all the legends we’ve absorbed. It’s why we drive our pickup trucks through the suburbs and tread the carpeted floors of air-conditioned offices in our cowboy boots.

Some of the greatest Texas movies ever made deal with those efforts to square our cowboy mythos with modern reality. It’s what you might call the Tex-istential crisis—the Texan’s search for meaning in a state that is no longer defined by, yet still firmly in the shadow of, its frontier past. In The Last Picture Show, it’s felt in the sense of purposelessness that descends upon a declining oil town, where bored residents mark time in a land that has been tamed until it’s nearly comatose. In Hud, the creep of modernity becomes a disease, souring the ground and driving Paul Newman’s immoral title character to increasing devilishness. Even The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, in its own violent way, is about this clash between New Texas and Old, with displaced agriculture workers taking out all their late-capitalist frustrations on some horny teenagers. In these stories, the Texans’ disenfranchisement is compounded by their isolation, by the sense that time is passing them by, and by the legacies of all those self-made mavericks who came before, to which their own drab lives bear little resemblance.

The Whole Shootin’ Match, directed by the late Eagle Pennell from a screenplay cowritten by Lin Sutherland, is among the most authentic films to ever grapple with this distinctly Texan malaise—not least because it was made by and about actual Texans. Pennell, an Andrews native who grew up around College Station before he moved to Austin, was well steeped in Texas fables, idolizing classic western-movie directors like John Ford, Howard Hawks, and John Huston. But whereas Ford et al. preferred to print the legend, Pennell’s 1978 debut feature is almost defiantly shaggy and naturalistic. It’s about ordinary Texans who dream as big and as wild as all those cowboy heroes Pennell grew up on, but whose realities have left them feeling trapped, unmoored, and uncertain between Texas’s past and its future.

Shot in a sleepy, now-bygone Austin, The Whole Shootin’ Match follows a couple of handymen named Frank and Loyd around as they eke out a meager living performing odd jobs, perpetually in search of the big score that will finally lift them out of the blue-collar bog. They scheme to get rich quick off everything from selling polyurethane to breeding chinchillas. But their plans are built on a house of cards; they all collapse at the first headwind. It probably doesn’t help that Frank and Loyd spend most of their days getting drunk.

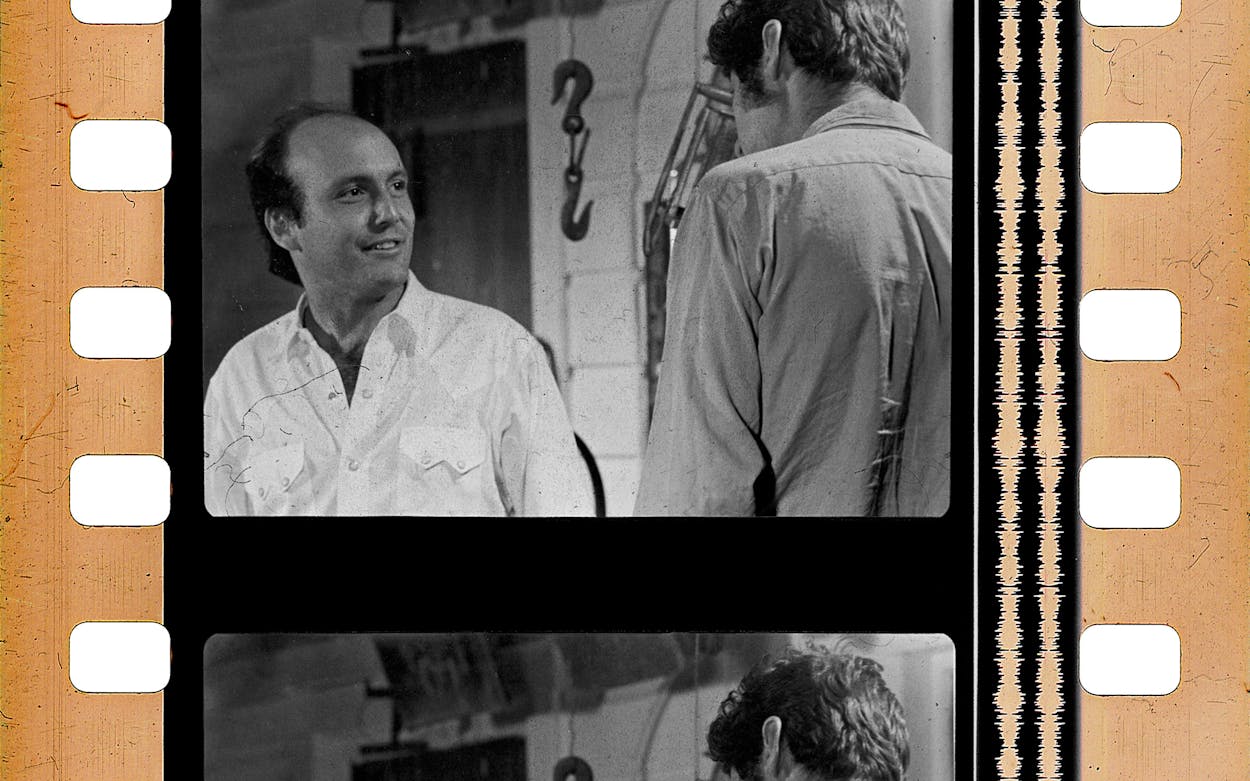

Loyd, played by Cooke County native Lou Perryman, is the more industrious of the pair, forever tinkering away in his woodshop and inventing new doohickeys out of scrap and spit. Loyd regards his fate not just as a matter of fortitude, but also as one of philosophy. In the film’s opening scenes, he lays out the divine secret of success to Frank, as revealed unto him by a mail-order business manual: “You gotta get your mind right,” Loyd says. Frank, played by Austin’s Sonny Carl Davis, is a touch more cynical. He’s no more beguiled by Loyd’s pie-in-the-sky ventures than he is by the lore of the “Indian gold” that his partner insists lies buried in the hills, nor by the promise of Jesus’s deliverance that’s offered by his heroically patient wife, Paulette (Doris Hargrave). Whenever Frank and Loyd’s latest ploy inevitably falls apart, Frank seethes—at Loyd, at Paulette, at his poor, blubbering kid. But mostly, Frank gets mad at himself for expecting things to turn out any differently. Then he cracks open another beer.

Film critic Roger Ebert, an early supporter of The Whole Shootin’ Match, once told Pennell that he’d made a movie about alcoholism, something the director claimed had never occurred to him. And indeed, Frank and Loyd probably would be better off if they’d sober up a little; it’s a lot easier to get your mind right when it’s not clouded by whiskey and Lone Star. Frank is a flawed man in a lot of other ways, too. He’s a liar and a womanizer, always running around on Paulette, then making teary promises to change that are completely forgotten by the next bender. He’s short-tempered and casually cruel: he taunts a Mexican family down at the drive-in, and he punishes his son for crying by whipping him with a belt. Like a lot of small-town big shots, Frank is way too hung up on high school, reliving his old football glories (and failures) down at the bar and holding on to petty adolescent grudges.

But while many of Frank’s problems can be blamed on his own considerable shortcomings, The Whole Shootin’ Match also suggests that at least some of his plight is geographical. As in The Last Picture Show, it’s the lingering specter of the Texas oil boom that’s filled Frank and Loyd with unreasonable expectations of instant fortune. That their own windfall hasn’t happened yet seems, to Frank and Loyd, almost arbitrary. It’s certainly not their fault. (In the film’s most candid moment, Frank confides to Loyd that he is “on the wrong side of thirty,” rapidly running out of time to get something going in his life. Loyd responds by suggesting they hit the town for an old-fashioned hell-raiser.) When Loyd does eventually stumble upon a million-dollar idea for a new kitchen gadget, then gets swindled by a patent lawyer, the men see this not as the result of their own folly, but as just another inevitable twist of fate. The world is stacked against ignorant “country boy[s],” they decide. All they can do is keep plugging away.

Beery optimism keeps Frank and Loyd afloat, but there’s also something innately Texan about their refusal to be licked. It’s a sense of shrugging acceptance that’s mirrored in Pennell and Sutherland’s script, which never tips into outright despair. Frank and Loyd’s many defeats are always balanced with light, ambling comedy; even at his most bitter or self-pitying, Frank is never far from breaking into a rascally grin. And while Frank and Paulette’s marriage is full of Sturm und Drang, it has moments of tender domestic bliss, too.

Most striking, especially for a movie of its time, is the way The Whole Shootin’ Match relishes the simple pleasures of driving aimlessly around town or dozing off in front of a Cowboys game, beer in hand. Such everyday vignettes give the film a well-worn veracity that was quietly revolutionary—like Britain’s kitchen sink realism reimagined for a world of checkered tablecloths, or the existential angst of French New Wave rejiggered as a sort of honky-tonk ennui. Even as Frank and Loyd’s story inches closer to full-bore tragedy, it wisely skirts any sensationalism or melodrama, concluding instead on a note of wry resilience that feels recognizably, achingly true.

What really makes The Whole Shootin’ Match feel true to life, however, are Perryman and Davis, who come off less like actors here than like a couple of salty cusses that have been rousted out of the local pool hall. Perryman, rangy and spirited, taps into Loyd’s guileless self-confidence without ever becoming a redneck caricature. Davis imbues Frank with enough rascally charm to smooth over the character’s rougher edges, making Frank lovable (or at least pitiable) even when he’s behaving like a drunken lout. He’s recognizable, too: there’s a certain way Davis laughs—impish and rowdy, his tongue snaking out between his teeth—that I’ve seen from a thousand good ol’ boys over the years, but rarely ever on-screen. To say that this is a case of their simply being Texans, rather than playing them, would unfairly diminish the actors’ talents. But the characters come off as so natural, and so intimately familiar, that they throw so many other Hollywood exaggerations of “the Texan” into stark relief.

That authenticity earned The Whole Shootin’ Match some powerful fans when it first screened at Dallas’s USA Film Festival in 1978. Among the people who caught one of the early screenings was Robert Redford, who later said it inspired him to create his Sundance Institute so he could help foster more “regional” filmmakers and stories. “Regional,” of course, is just a nice way of saying that the film used actors, not movie stars—something that would have made The Whole Shootin’ Match a lot less believable, and certainly less remarkable. (Perryman had notched just a single film credit, the horror spoof The Tomato That Ate Cleveland, before he joined up with Davis and Pennell on the 1977 short A Hell of a Note. Davis was primarily a musician who played around Austin.) It definitely helps that Davis and Perryman look like guys you grew up around whose own dreams never quite panned out. Had Frank and Loyd been played by, say, Dennis Hopper and George Kennedy, the suspension of disbelief would have been too great; all those small, affecting moments would have come off as big and phony. Pennell’s decision to keep things local would leave a lasting impression on director Richard Linklater as well, who credits Pennell as a direct influence on his own career of making movies in his Austin backyard that star more genuine Texans.

Unfortunately, the acclaim for The Whole Shootin’ Match seemed to be the worst thing that could have happened for Pennell. He didn’t just worship John Ford’s and John Huston’s ways with a yarn, after all. He also imitated their penchant for binge-drinking and brawling, and his self-indulgence was only exacerbated by the film’s sudden success and its validation of Pennell’s considerable ego. When Pennell died in 2002, just shy of his fiftieth birthday, he left behind a raft of jilted former friends and collaborators and the tatters of a once-promising career that—like his hapless alter egos on film—he’d managed to sabotage through his own impulsiveness and personal demons. The 2008 documentary The King of Texas, directed by Eagle’s nephew, René Pinnell, lays all of this out in frank and loving detail; you can find it on the Whole Shootin’ Match DVD and on YouTube.

After The Whole Shootin’ Match, Davis continued to enjoy a long career as a character actor, turning up in pieces such as Melvin and Howard, Lonesome Dove, and Bernie. These days, he’s probably best known as the irate customer who tells Judge Reinhold to put his “little hand back in the cash register” in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, or from the Richard Linklater–directed political ad in which he puts Ted Cruz on blast. Perryman kept acting as well, turning up in movies like The Blues Brothers, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and Boys Don’t Cry before more or less retiring from show business in the early 2000s. I was fortunate enough to interview Davis and Perryman in 2008, when Perryman told me of his hopes that the two would reunite on another project that would be just as meaningful as The Whole Shootin’ Match, which he still considered to be the best thing he’d ever done. “Some people are just boring, and g—damn it, we’re not,” Perryman told me. “We were doing something that mattered to us.”

Tragically, Perryman was murdered in 2009, killed by a stranger who just happened to find him at home. His plans for a new adventure with Davis as his partner never materialized. But if there is any consolation, perhaps, it’s that Perryman lived long enough to see The Whole Shootin’ Match restored, its prints rescued by producer Mark Rance from the German buyer to whom Pennell had sold them for drinking money, and finally given the veneration it so richly deserves as a landmark of both Texas and independent cinema. Still, it sure would have been nice to see Perryman play a Texan again in his august years. Like Davis, he’s one of the greatest to ever do it.

The trio of Pennell, Davis, and Perryman did manage to team up once more on 1983’s Last Night at the Alamo, a similarly lo-fi and discursive tale about Houston barflies facing down the final last call at their favorite watering hole, which is soon to be gentrified out of existence. Its screenplay, from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s Kim Henkel, is fairly unsubtle with its metaphors about the rapid disappearance of Old Texas and the restless rootlessness this has fostered in all the sundry ranchers and roughnecks now living in the shadows of skyscrapers. Davis’s character is even named Cowboy. As he explains to his partner, Claude, played by Perryman, Cowboy nurses a drunken dream of heading out west to become the next John Wayne in Hollywood—someplace he can live out that Old Texas mythos, in the only realm where it still exists.

“They don’t have those guys out there anymore,” Cowboy tells Claude, adding with palpable disdain, “They got Clint Eastwood, or Robert Redford, or John Travolta. . . . They need guys like us.” Cowboy is right, although not in the way he means it. Film did need guys like that. And our culture got a whole lot richer once there were fewer cowboys and more Cowboys—and more Loyds and Franks—starring in thoughtful stories that saw Texans as complex, fallible people, not just stereotypes in Stetsons. Thanks in no small part to The Whole Shootin’ Match, playing a Texan, just like being a Texan, became a matter of getting your mind right.