Shea Serrano’s Primo, which premiered in May on Amazon’s Freevee service, is as Texas as TV gets. The San Antonio–based comedy is loosely based on the childhood of its creator, a native of the Alamo City who worked as a school teacher in Houston, collaborated on a coloring book with Bun B, and can tell you every detail of the Spurs dynasty. The series, cocreated with The Good Place’s Mike Schur, is a coming-of-age story about a Texas teen who’s trying to navigate high school with the guidance of his five wildly different uncles, with distinct details that most residents of the Lone Star State can relate to—the cookouts, the trips to Six Flags, the sports fandom, meals at Whataburger, etc., etc., etc. But for all of its Texas specificity, Primo wasn’t actually made in Texas. The series was filmed in Albuquerque, owing to New Mexico’s well-funded incentives program. Our neighbor offers a credit between 25 and 35 percent of the project’s in-state spending to productions that shoot in the state, spending around $130 million per year to bring more than $850 million in production spending to the state. Texas’s film incentives program, meanwhile, had maxed out, since its peak of $90 million in 2013, at a total of $45 million for each two-year period for which the state budget appropriations apply.

Primo is hardly the only Texas-based series to actually be filmed elsewhere. Netflix’s Selena series, which premiered in 2020 and was shot largely in Baja, California, featured a hilariously inaccurate depiction of the Rio Grande Valley. (The famously low-lying South Texas region is depicted as mountainous, raising the question of whether anyone at Netflix knows what “valley” means). Even having the word “Texas” in its name doesn’t mean a show was actually filmed here—NBC’s Midnight, Texas was shot in New Mexico. For movies, the list is long—The Forever Purge, set in El Paso, was shot in California; the 2018 thriller Galveston was shot in Savannah, Georgia; Netflix’s 2019 Bonnie and Clyde story was filmed in Louisiana; the 2022 surprise Oscar contender To Leslie, set in West Texas, was shot in Los Angeles. The dearth of incentives to film in Texas has spanned years—principal photography for 2007’s No Country for Old Men and 2018’s The Old Man and the Gun took place in New Mexico and Ohio, respectively, with a few scenes shot in Texas to add authenticity.

Red Sanders, a Texas Christian University film graduate who opted to hang out a shingle in Fort Worth rather than move to Los Angeles, started Red Productions in 2005. In addition to producing music videos, commercials, and independent films, he’s been active in the effort to get the state legislature to provide more funding for the incentives program. He related to me a story about testifying before a House committee. “The chair of that committee, who represented an area in West Texas, said to me, ‘I remember seeing this movie recently called Hell or High Water, which is set in my district, but I don’t remember any mountains in my district,’ ” Sanders said. “I was like, ‘Yeah, that was shot in New Mexico, because Texas didn’t have the incentives to support it then.’ ”

Texas legislators are a proud people, and the idea that New Mexico could be dressed up to pass as the state in mass entertainment doesn’t sit well with many of them. That’s part of why, in the 2023 session, the appropriations for the film incentives program shot up dramatically—from the $45 million of previous sessions, which would usually be depleted within about six months, to a more robust $200 million. That number makes Texas competitive with neighbors such as New Mexico and Louisiana, each of which have invested heavily in film production. The goal, according to Sanders and others in the Texas film community, is to use the $200 million as a kind of down payment that could lead to ongoing production throughout the state. Rather than productions coming through, tapping the incentives program until it’s dry, and then waiting until the next odd-numbered year, productions could shoot constantly, creating a full-time class of crew members who could call Texas home year-round. If that works, folks from local film commissions or the statewide Texas Media Production Alliance (TXMPA) argue, the return on investment could be around five dollars in economic activity for every dollar the state spends on production. The next steps would be to build a permanent structure for funding the program that’s not subject to the whims of the Lege, and to increase investment not just in incentives but also facilities and crews that could help Texas compete with the states that have seen film production become a major industry over the past few decades.

“I don’t think most legislators understood [until this session] that Marvel hasn’t filmed a movie in California in ten years,” Sanders told me. The studio has invested heavily in production facilities in Georgia, where it shoots the bulk of its features and TV projects. Georgia is the current king of film production incentives, spending close to a billion dollars per year to lure and keep the industry spending nearly $4.5 billion in the state each year. Texas may not be competing with Georgia in the short term, but industry folks in the state can imagine getting there in the future.

In May, as the Lege was negotiating the budget, Houston filmmaker Jeremy John Wells shot a PSA in which Woody Harrelson, Matthew McConaughey, Glen Powell, Dennis Quaid, Billy Bob Thornton, and Owen Wilson urge members to boost the incentives program. I asked Wells after the budget passed if Texas could become a Georgia-sized player in the industry. “I mean, why not?” he told me. “Texas has something really unique. There are seven distinct geographical regions to Texas—you’ve got the desert, the coast, the forests . . . not many states have that kind of variety, and a lot of times, you’re deciding where your project is going to be based on those practical applications. And Texas is so business-savvy that it just makes sense.”

The incentives program has gone from being an afterthought that gets used as a political football—in previous sessions, lawmakers who opposed the funding described it as a “handout for Hollywood,” framing it as giving Texas-taxpayer dollars to rich Los Angeles film producers and movie stars—to, suddenly, a robustly funded program that has industry advocates throughout the state salivating at the prospect of what they might be able to get done in the next legislative session. Film professionals in Texas are more excited than ever about the possibility that their home state might finally compete with the biggest players in entertainment. Could one of the most famously progressive industries in the country really thrive in one of the most conservative states in the union?

The “handout for Hollywood” frame for the film incentives program was always reductive. Film production touches a huge number of local industries in any city where filming takes place—think caterers and restaurants feeding crews, lumberyards and carpenters building sets, hotels putting up cast and crew from out of town, all the way down to the companies that rent port-a-potties that crew members will use on set. Still, that hasn’t stopped lawmakers who oppose the program from casting the money appropriated for film incentives as a direct transfer of $45 million from hardworking Texas taxpayers directly to George Clooney’s pocket. “These programs have been used for inappropriate uses,” state representative Matt Shaheen, who introduced legislation that would have ended the program entirely in previous sessions, told the Texas Tribune in 2015. “Hard-earned taxpayer dollars have gone to Hollywood actors that have polarizing stances within our nation.” Others have pointed out that productions have still opted to film in Texas even with a low incentives budget, calling into question whether such a program was needed at all. (Advocates for the program have argued that one-off productions aren’t enough to build a sustainable industry in Texas; in 2017, Rooster Teeth’s then-CEO Matt Hullum told me that “an incentives program makes a stable work environment for film and TV here in Texas.”)

In this year’s legislative session, though, opposition was minimal. Shaheen still objected—he told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in March that “we just don’t need to take taxpayer dollars from sin”—and a representative from the social justice think tank Every Texan testified against a bill that would have similarly boosted film incentive spending by noting, among other concerns, that the economic benefits of incentives in other states may be exaggerated. Still, during the appropriations process funding the incentives program, lawmakers found consensus at $200 million for the program.

There are a few reasons for this: First, the state’s extraordinary budget surplus made spending on economic development programs a little more palatable to lawmakers who were extremely frugal in previous sessions. Second, there was a strong effort from the film community to reach out to lawmakers, including private screenings and set visits, to help them understand that the people who benefit from these programs are carpenters and caterers, not Matt Damon and Sean Penn.

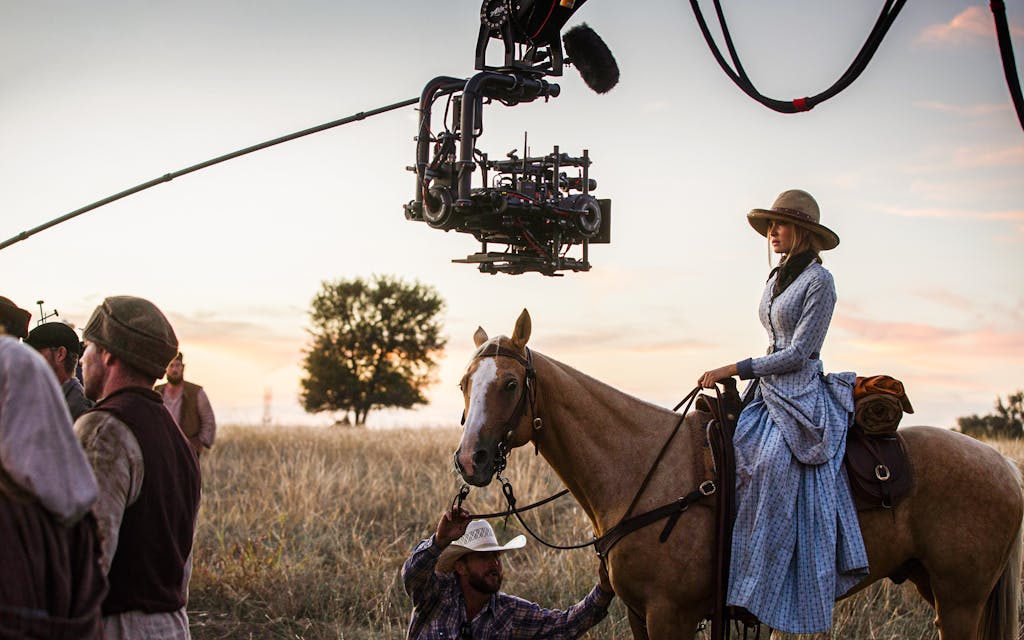

But perhaps even more influential was the fact that the productions that have been occurring in Texas in recent years have been the sort that the conservatives that control the state’s budget can get behind. A few names came up whenever I talked to anyone in the film industry about what changed the reputation of the industry among Texas lawmakers: Taylor Sheridan, whose Yellowstone empire includes 1883, as well as the forthcoming Land Man (cocreated by Texas Monthly’s Christian Wallace and based on the Texas Monthly podcast Boomtown), all of which film in Texas; the Gaineses, the Baylor grads whose Fixer Upper and Magnolia Network have transformed Waco into one of the state’s more improbable tourist destinations; and the creators and producers of The Chosen, the Midlothian-shot independent crowdfunded series that, in telling the story of Jesus with HBO-level production values, has become an unprecedented phenomenon despite being self-distributed. I asked Wells if that had an impact. “Unequivocally,” he told me. “If you want to look at who to credit for the recent change in public opinion, specifically at the legislative level, one hundred percent credit those guys.” Whether those projects are political at all—let alone conservative in nature—is a discussion for the critics. But they definitely have an appeal to lawmakers who were turned off by previous applications to the incentives program, such as Robert Rodriguez’s 2010 feature Machete, in which Robert DeNiro plays a corrupt Texas state senator. (The Texas Film Commission refused to provide incentives to that film, citing a clause in the program that requires projects to present the state in a positive light.)

Mindy Raymond, communications director for the TXMPA, has seen the incentives program’s budget fluctuate wildly in her time with the lobbying organization that represents the film industry at the Lege. She told me that the change in attitude at the Capitol this session has been “really interesting.”

“Look, we know what the makeup of our Legislature is, right?” Raymond told me. “We understand that, yes, these projects are something that they’re looking at and getting behind because of the conservative nature of the Lege. We understand that fully. We use The Chosen and Taylor Sheridan because that is content the Lege gets behind and wants to see more of, but our membership base includes folks from all different genres.”

Raymond sees the interest generated by those shows more as an opportunity to educate lawmakers on the real financial impact of the incentives program than a reason to believe that future projects will necessarily be conservative-coded. “The Texas Film Commission looks at the economic impact—what’s going to bring the greatest return for the taxpayer back for various projects across Texas?” she said, noting that the incident around Machete was the first and last time the stipulation around the way a project represented Texas was invoked. “We’re not in the business of curating content or picking winners and losers,” she said. “We just want to tell Texas stories in Texas.”

Twenty-five miles southwest of Dallas on US-67, Midlothian is the sort of booming Texas exurb that’s driven the state’s growth in recent decades. A small town with less than 10,000 residents as recently as the early aughts, the city now boasts a population of nearly 40,000. When The Chosen needed a new shooting location for its third season, Midlothian wasn’t exactly on the radar.

The Chosen, which was created by Illinois native Dallas Jenkins, filmed its first season in Weatherford, west of Fort Worth, in 2019, but as an independently produced and distributed series, it didn’t exactly find its audience quickly. In 2020, during the dire stay-at-home months of the pandemic, an audience hungry for new content and interested in seeing the New Testament presented with a vibrant, contemporary sensibility, found it. The show went from distributing solely on its own app to deals with streaming services such as Peacock, Amazon Prime, and Netflix.

The Chosen didn’t receive any incentives for that first season in Weatherford—a spokesperson for the show told me that the program was out of money when they applied—and production moved to Utah for season two, where they received incentives funding. When it came time to actually find a location to film that transformative third season, though, The Chosen had very specific needs—and looked, once more, to Texas. The production required a long-term base it could use over the course of the planned next five seasons, where producers could confidently invest millions in building out a functional replica of Jerusalem on many hundreds of acres over a landscape that could pass for the Holy City, as well as support facilities. Meanwhile, in Midlothian, Camp Hoblitzelle, a Salvation Army camp, was struggling to survive the pandemic without campers. An employee of the camp who was a fan of the show reached out to the producers, who took a tour of the facility.

“We’re on golf carts going around the camp, and we’re like, ‘Well, this is great, but this isn’t a summer camp show. We’re a Jesus thing that needs empty fields,’ ” Chad Gundersen, the show’s co-executive producer, recalled. “So I said, ‘Thank you very much, but we just need more space. And then Casey, the camp director, kind of looks at me and says, ‘We haven’t seen the property yet. We’ve only seen the camp.’ So he drives to the back of the camp, and we open a gate, and drive out into the middle of this field. And Casey says, ‘You’re now seeing a very small fraction of the seven hundred acres that we have.’ We weren’t driving for two minutes on these golf carts when Dallas goes, ‘Wait, wait, wait, stop.’ He gets out and does the filmmaker thing, creating a box with his fingers, and he says, ‘I can see no less than ten scenes in this field alone. I think we’ve found our home.’ ”

The Chosen’s investment in Midlothian is enormous. In addition to the lease on Camp Hoblitzelle, the show’s producers are building facilities—a 30,000-foot soundstage, the largest purpose-built facility of its kind in the state of Texas, as well as another 30,000-foot support building. “It’s got a mill; hair, makeup, and wardrobe facilities; and a dining hall,” Gundersen explained. The Chosen employs around five hundred crew members when it’s in production, and in return, the show is eligible for incentives up to 20 percent of its budget. Gundersen is quick to point out how many different kinds of businesses a production that size touches. “We employ doctors, we employ attorneys, we employ writers. We had an archery specialist on set the other day,” he told me. “We actually need more—more qualified people, more facilities, more hotels, more restaurants, all these things. Midlothian has embraced and supported us, and we love being there—going out to the restaurants and going to their Walmart and buying the stuff that supports the people we have on set every day.” The show is in the queue to receive credits from the incentives program for its third and fourth season, with no guarantees that it will receive them. Producers are optimistic that the new funding means that they’ll be able to take advantage of the program for its fifth season and beyond.

Should the flush incentives program lead to the level of production that industry experts expect it to, the next challenge will be ensuring that there’s enough trained crew and infrastructure to support it. The incentives program, which used to require 70 percent of crew members be based in Texas to qualify, dropped the requirement to 55 percent this session in acknowledgment of that concern—for the time being, at least, there are only so many qualified crews to go around. The hope, according to Gundersen, is that if there’s a steady amount of work throughout the state, then a fair number of the camera operators, lighting grips, sound technicians, hair and makeup artists, and others who come to Texas to work might put down stakes to stick around. “Heck, even our director, Dallas, moved to Texas since the start of the show,” he told me.

In addition to minting new Texans in the film industry who might relocate to the state from elsewhere, there are wheels in motion to get folks who are already here who previously wouldn’t have had an opportunity to work on movies or TV shows trained up for the job. The Chosen uses Camp Hobiltzelle to host filmmaking camps for local teens and college students, giving young Texans the chance to see opportunities for themselves in the industry that don’t involve moving to Hollywood, New York, or Atlanta. “One of the great things that came out of that is that these kids just get this gleam in their eye and start going, ‘Oh, wait a minute, I can actually do this,’ ” he said.

It’s all tremendously exciting, if you’re a Texas filmmaker who’s been beating your head against the wall of a state legislature that has opted not to compete with neighboring states such as Louisiana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma when it comes to incentivizing production. But this push to finally become a more serious player in the entertainment industry also comes as the state takes an even sharper rightward lurch on social issues. It remains to be seen if those two pursuits are compatible.

David Simon is one of the more significant names in television in the past twenty years. The Wire, the police drama he created for HBO in 2002, is one of the definitive shows of television’s golden age. He followed it up with two series that ran for a combined seven seasons, Treme and The Deuce, as well as a number of miniseries: Show Me a Hero, The Plot Against America, and We Own This City, all also with HBO. But in 2021, as Simon was scouting locations for a not-yet-greenlit project he’s developing, he ruled out Dallas, despite it being the city in which the story is set.

“I’m turning in scripts next month on an HBO non-fiction miniseries based on events in Texas, but I can’t and won’t ask female cast/crew to forgo civil liberties to film there,” he posted on Twitter that September, shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the state’s abortion “bounty” law, Senate Bill 8, to go into effect. “What else looks like Dallas/Ft. Worth?”

The project, a miniseries about the first Muslim FBI agent—who worked for much of his career out of the bureau’s DFW field office in the years after the 1993 World Trade Center bombing—is still in development, but according to Laura Schwarzman at Simon’s production company, he was looking at locations in L.A. and New Mexico to pass as Texas. “David’s commitment to not cross a line involving reproductive health care for his employees remains intact,” she told me. “He won’t film in any jurisdiction where he is obligated to ask cast or crew to sacrifice their civil liberties in order to do their job.”

The impact on production of Texas’s litany of restrictive laws targeting abortion, drag shows, transgender teens, and other issues that are important to progressively minded Americans—a group well-represented in the entertainment industry—will be hard to gauge. Few filmmakers have actively declared that they won’t bring crews to a state where they can’t access abortion care or hormone therapy for their kids, but anytime a project that could have begun production in Texas starts rolling in California, New Mexico, or Vancouver, it’ll be fair to wonder if the political environment in the state was a factor.

For Owen Egerton, director of the 2019 Netflix horror feature Mercy Black and the 2018 Rooster Teeth horror-comedy Blood Fest, getting out of Texas wasn’t so much an act of political protest as it was a matter of protecting his family. When we spoke, Egerton, whose daughter is transgender, was in the final stages of packing up his Austin home for a move to Boston, where he’d recently accepted a job as a screenwriting professor.

“I don’t know if I’ll be shooting my next film in Texas,” he told me during a break from loading boxes into a storage pod in his driveway. “There’s not a lot of encouragement to come to a state where the government says that my daughter shouldn’t exist, so I would rather film somewhere else.”

For Texas to be competitive with production-heavy states such as California, Georgia, and New York, it’ll need to see a consistent, ongoing base of projects filming throughout the year. That’s the difference between a crew flying in for a few weeks, staying in a hotel, and filming a movie, versus having a permanent crew base that resides in Texas year-round, ensuring that any production that wants to film in Texas knows it’ll be able to find the talent it needs. Everyone I spoke with for this story—including Egerton, who moved to Texas when he was two years old and has complicated feelings about the state—would prefer the latter to the former. It won’t be possible to get there off of The Chosen and Taylor Sheridan projects alone, and those projects will need long-term industry investment to thrive and grow the way their creators envision.

The Texas film community has few advocates more integral than Red Sanders. In almost any conversation you have with a player in the industry about the push to bring more production to Texas, his name comes up. He’s got relationships with filmmakers, politicians, lobbyists, and activists, both within Texas and without. When we spoke for this story, he was in Manhattan, where the music video he produced for the Kendrick Lamar song “N95” was being entered into the archives at the Museum of Modern Art. He serves on the executive team of the TXMPA and was a founding member of the Fort Worth Film Commission. And, as the new level of funding the incentives program has seen in the most recent session indicates, he’s been more successful than anyone might have guessed in achieving his goal. He’s got every reason to be bullish about the possibilities for the film industry in Texas—and in a lot of ways, he is. But even he doesn’t know if the future for Texas filmmaking is as bright as it should be. “We’re making headwinds on the business side of it, but then we’re, in some ways, creating new wind against us on social issues,” he told me.

All of which leaves the story of the Texas film industry at something of a crossroads. On the one hand: Texas is courting an industry where the values of much of the talent base may differ from those of the legislators who pass restrictive laws around issues they care about. On the other: The business of filmmaking has more support than ever from the state, and the folks who draw up the budgets might choose to follow the money. It may be a complicated dynamic, but resolving conflict in stories is something that the film industry has always been good at.

“Wouldn’t it be a wonderful, ironic, beautiful thing if, because of the incentives of this Legislature, a young trans Texas filmmaker is able to get her voice and her story out there, and that movie, that show, that piece of art saves lives that this Legislature is trying to hurt?” Egerton asked me, as he reflected on his hopes for an incentives program that he himself would have taken advantage of under other circumstances. “Wouldn’t it be amazing if art could win out?”