This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

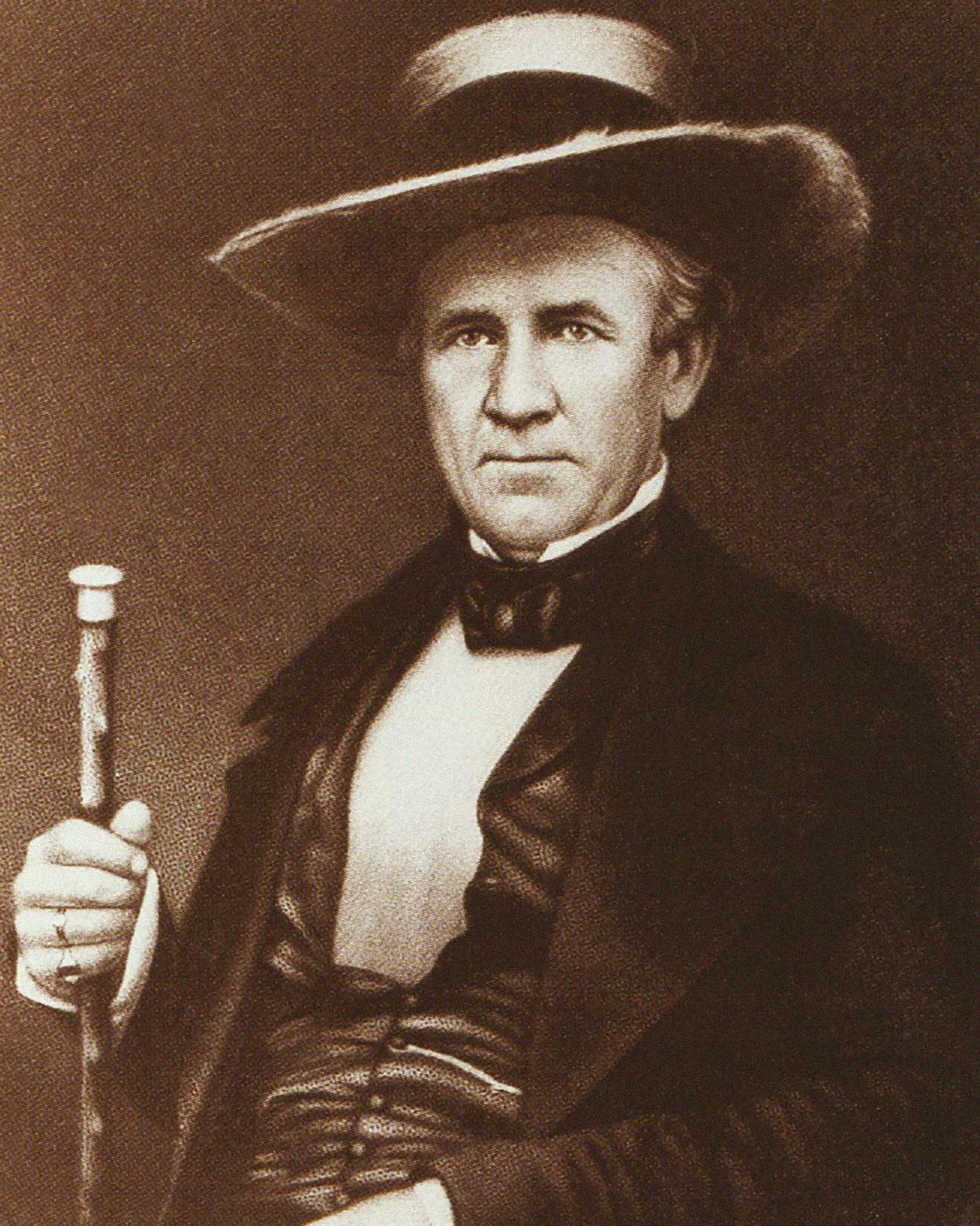

No one ever called Stephen F. Austin “Steve,” or Charles Goodnight “Chuck,” or Lyndon Baines Johnson “Lyndy.” But Sam Houston was always just Sam. Texas’ greatest hero crushed Santa Anna’s army at San Jacinto, a feat that propelled him into a lifetime of political service as our president, governor, and U.S. senator. Yet Sam Houston never lost the folksy charm and human flaws that made him a sort of Texas Everyman.

Sam was born two centuries ago this month, and the state is gearing up for a full-fledged shindig to mark the occasion: more than fifty events in sixteen locales, from a graveside memorial service in Huntsville to a re-creation of the Runaway Scrape in Gonzales County. Simultaneously, the hefty library of Sam Houston literature is gaining two brand-new biographies (reviewed here, along with eight other significant Sam books). No other Texan has ever received such a tribute, but no other Texan has ever embodied so fully the fundamental virtues (and vices) that define the state. Like so many other ragtag émigrés, Sam had “G.T.T.” (Gone to Texas) to escape an unfortunate past (in his case, a scandalous failed marriage while the governor of Tennessee). In some ways he behaved shockingly—boozing it up in public, flaunting his affection for the Indians—but he nonetheless managed to turn a beleaguered wilderness into a functioning republic recognized worldwide. He was tall, friendly, and brave, with a tendency to embroider the tales of his many exploits. Herewith, a selection of the accomplishments, embarrassments, imbroglios, and other moments of truth in the life of the ultimate Texan.

Sam at a Glance

1793: Born in Rockbridge County, Virginia.

1809: Runs away to live with the Cherokee.

1813: Joins the U.S. Army.

1814: Severely wounded during the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

1823: Elected U.S. representative from Tennessee.

1827: Elected governor of Tennessee.

1829: Marries, then loses, Eliza Allen; returns to the Cherokee.

1832: Arrives in Texas.

1835: Named commander in chief of the Texas military forces.

1836: Routs Santa Anna’s army at the Battle of San Jacinto; elected president of the Republic of Texas later that year.

1840: Marries Margaret Moffette Lea.

1841: Reelected president of the Republic.

1846: Elected U.S. senator from Texas; serves thirteen years.

1859: Elected governor of Texas.

1861: Refuses to swear an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy; the Texas legislature declares his office vacant.

1863: Dies at home in Huntsville.

Frippery Fop

Sam was a dandy. Despite his impecunious life, he always managed to dress well (or at least flamboyantly). He once paid a visit to John Calhoun, then U.S. Secretary of War, clad in buckskins and feathers; received the British chargé d’affaires to Texas swathed in a red silk caftan; and addressed the U.S. Congress in a silk suit with a vest variously described as cougar, leopard, or jaguar hide. For more mundane duties, he habitually donned an Indian blanket or a Mexican serape.

Indian Interlude

Young Sam’s favorite book was The Iliad. Perhaps that is why, in 1809, sixteen-year-old Sam ran away to live with the Cherokee, the closest local equivalent to the Homeric warrior society. He was adopted by Chief Ooleteka, also known as John Jolly, and stayed with the tribe for almost three years; he later returned in times of trouble. For the rest of his life, he sought to defend his Cherokee family and many other tribes.

The Raven

Walk in My Soul: The Story of Tiana of the Cherokee, the Young Sam Houston, and the Trail of Tears

Lucia St. Clair Robson (Ballantine Books, New York, 1985). A historical novel is the only way to bring to life Tiana Rogers, Sam’s Cherokee wife, about whom contemporary sources recorded little more than the fact that she was “graceful as the bounding deer.” Inevitably, the stilted translations of Cherokee dialect (including the title, a tribal love incantation) get a little silly, but Robson, who also fictionalized the life of Comanche captive Cynthia Ann Parker, has based her protagonists’ adventures on the facts, and she enlivens things further with the romance novel’s requisite number of births, deaths, and couplings. Not history, and not literature, but definitely fun.

Sword of San Jacinto

Foe Pause

Even for a politican, Sam had a lot of enemies. Alexis de Tocqueville called him one of the “unpleasant consequences of popular sovereignty.” Various adversaries called him “Sam Jacinto,” “Sham Houston,” “the Texas rowdy,” “a preposterous vulgarian,” “an incubus upon the land,” a “damn old drunk Cherokee,” and “the Munchausen president.” (The last slur, uttered by longtime rival Mirabeau B. Lamar, referred to the German adventurer Baron Munchausen, known for his hyperbolic exploits.)

Battle Acts

A soldier’s soldier, Sam suffered three serious wounds in battle. In 1814, serving under Andrew Jackson during a battle with the Creek tribe, he sustained a near-fatal arrow wound in the groin and a rifle wound in the right shoulder. According to Sam’s family doctor, Ashbel Smith, the arrow injury “remained a running sore to his grave.” Twenty-two years later, a Mexican musket ball shattered Sam’s right ankle at San Jacinto.

The Eagle and the Raven

Hits and Messes

Violence was a way of life for Sam. During a two-year period in the 1820’s, for example, he fought an abortive duel, drunkenly assaulted his adoptive Indian father, and severely beat with his cane a congressman who had insulted him in the House of Representatives. Although he was charged with assault and battery for this last offense, he escaped punishment by wowing Congress with a florid self-vindicating speech, delivered despite a major hangover.

The Face of Race

Sam opposed secession—but not because he hated slavery. Although family legend holds that Sam freed his slaves on the brink of the Civil War, an inventory of his estate after his death listed twelve Negroes worth $10,530. Despite his fabled championship of Indians, Houston was a man of his era as far as other minorities were concerned. As part of a pre–San Jacinto pep talk, he railed against tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent), and another time he claimed that Mexicans were “incapable of self-government.”

He No Alamo!

If William Barret Travis had listened to his commander in chief, the Alamo would never have fallen. Two months before the siege, Sam had issued orders to “blow up the Alamo and abandon the place,” but hotheaded Travis disregarded his general’s wishes. So where was Houston during the fall of the Alamo? In Washington-on-the-Brazos, then Texas’ scruffy little capital, trying to forge a constitution and a government for his emerging nation. When he received news of the Alamo’s defeat, he ordered his army to retreat eastward and urged civilians to follow. This ignominious exodus became known as the Runaway Scrape, as terrified Texans abandoned their homes and farms to escape the dreaded despot Santa Anna. One family fled so fast that they left their supper of fried chicken congealing on the table.

Empire of Bones: A Novel of Sam Houston and the Texas Revolution

Jeff Long (William Morrow, New York, 1993). This eloquent novel by an Alamo historian focuses on the Runaway Scrape and the Battle of San Jacinto. Despite a rather contrived prologue in which we witness the very end of the Alamo defense through the eyes of Davy Crockett (“As high and as deep as he could throw it, Crockett released his soul toward the dawn”), Long has produced an unsettling portrait of the confusion of battle and the horrors of victory and defeat: a corpse with buzzard-pecked eyes, a human ghoul feeding on the dead, a soldier wearing a necklace of blackening Mexican ears. He punches most of Texas’ buttons—bluebonnets blanket the battlefield, for instance—and throws in for good measure a few Western capers like a buffalo stampede and a hanging. On the eve of the battle, Long’s bemused Sam trims his toenails and has a quick tumble with legendary termagant Pamela Mann.

A Man of Spirits

Sam was all too fond of the bottle: He even termed alcohol his “fatal enchantress.” In the 1830’s, during his second fling at life as a Cherokee, his fellow braves dropped the war title “Raven” for the more fitting “Big Drunk.” Biographer Marquis James termed his first presidential administration the “Bachelor Republic,” as Houston and his underlings routinely drank themselves senseless. Once, staying at the home of a judge in his namesake town, he grew so inebriated that he chopped off the posts of his bedstead with an ax. But after his marriage to Margaret Lea—a devout Christian and rabid teetotaler—he eventually came to spurn alcohol.

Bigwigging

Sam rubbed elbows with hundreds of fellow celebrities in his life, including his role model, Andrew Jackson, and other American historical luminaries such as Robert E. Lee, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, Thomas Hart Benton, Francis Scott Key, Aaron Burr, Samuel Colt, Washington Irving, six U.S. presidents, and, of course, his fellow transplanted Texan, Davy Crockett.

Horse Sense

Almost as famous as his owner was Saracen, the white stallion Sam rode into battle at San Jacinto. But Sam had owned Saracen only a short while, and the horse was, in fact, one of the few Texas casualties of the eighteen-minute battle.

Tall Tale

Legend notwithstanding, Sam wasn’t six feet six. On a passport application in 1832, he listed his height as six feet two.

Buckskin Romeo

Sam loved women. A lifelong whittler, he carved tiny baskets from peach pits or hearts from wood scraps to present to attractive females. To a longtime heartthrob, Anna Raguet, he sent “laurels” (probably magnolia leaves) from the battlefield of San Jacinto. Sam was the constant recipient of fan and love letters, but after his death Margaret burned hundreds of missives from other women.

Sam Houston: The Great Designer

Llerena Friend (University of Texas Press, Austin, 1954). Sam would have loved the little irony that underpins this historian’s history. Friend wrote the biography in part because the Daughters of the Republic of Texas awarded her the Clara Driscoll Scholarship for Research in Texas History two years in a row. But after extensive combing of public records nationwide (and even detailing a friend to “cut for Sam’s sign” in England), the author ultimately portrayed Sam not as a Texas hero but as an American patriot. Declining to dwell on his shortcomings, she hews to the path of Sam’s political vision. In her straightforward interrogative style—“What the devil was Sam Houston doing in Texas?”—she separates fact from folklore and draws convincing conclusions. Two thirds of Friend’s book focuses on Sam as senator and governor, which provides significantly more than the casual reader might care to know about, say, the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, but the author leavens the academic stretches with funny tidbits about Sam’s family life or juicy remarks by Sam-baiters.

Sam Houston: A Biography of the Father of Texas

John Hoyt Williams (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1993). This Sam Houston bio delivers its biggest whammy before the reader even turns the first page: the epithet in the subtitle. Williams’ application is almost heretical, but even the most casual student of Texas history would have to agree that the title “Father of Texas” fits Sam as well as it does Stephen F. Austin. A professor of history at Indiana State University, Williams has a readable style that proves the perusal of history need not be painful. His writing is also refreshingly free of the hero worship that permeates earlier biographies; whereas Marquis James wrote that “whisky helped to blunt memories,” Williams says pithily, “Sam Houston went on a toot.”

Sects Appeal

Described as “hostile to Christians and Christianity” by a missionary to the Cherokee tribe, Sam rarely attended church in his younger days, preferring instead the unwritten naturalism of his Indian brethren. Later, possibly as a political move, he attempted to join the Presbyterian church but was refused baptism because of his separation from his first wife. In 1833, however, he became a Roman Catholic in what Marshall De Bruhl termed “a baptism of convenience,” because a profession of that faith was required by Mexico of all prospective settlers in Texas. At age 61, thanks to Margaret’s influence, he again joined a church, this time for good. The denomination was Baptist, and Sam endured complete immersion in an icy-cold creek during a November norther. According to legend, when a friend informed him, “General, all your sins have been washed away,” Houston replied, “If that be the case, Lord help the fish down below!”

Sam Houston: American Giant

M. K. Wisehart (Robert B. Luce, Washington, 1962). Based on the eight-volume Writings of Sam Houston, this bio strives for thoroughness, even noting the 1843 purchase of “4 Bolts of linen Diaper” for the giant’s first child, Sam Junior. Benefiting from the advice of J. Frank Dobie and Walter Prescott Webb, author Wisehart chose to “give [Houston] the floor,” so the great man’s flowery, impassioned quotes carry many chapters. Wisehart’s work is of especial interest to Civil War buffs; it offers a thorough analysis of the Jacksonian Democrat’s pro-slavery, anti-secession stance (in protest to which seething crowds gathered everywhere he traveled, shouting, “Kill him! Kill him!”). Small wonder that Sam’s consideration of an 1860 bid for the U.S. presidency died an abrupt death.

Young Hickory

Andrew Jackson was Houston’s political and personal mentor, and the lives of the two were remarkably similar. Each lived on the frontier, worked as a lawyer, fought as a soldier, inherited a catchy nickname, ran successfully for the U.S. Senate, opposed states’ rights, enjoyed wide popular appeal, and endured a marriage scandal (Jackson’s wife, Rachel, had been married before, and her divorce had not been final when they wed). When Jackson died, Sam brought Sam Junior, then two years old, to view the body.

The Belle’s Toll

In 1829, while the Governor of Tennessee, Sam married twenty-year-old Eliza Allen, a gently reared blond sixteen years his junior. Three months later, she left him. Scandalized, residents of Eliza’s hometown went so far as to burn the governor in effigy. No one knows why Eliza left Sam; both parties kept the secret to their graves. Historians have speculated that the sheltered maiden was repulsed by her groom’s still-suppurating groin wound, that she was not a virgin, that she loved another man. Whatever the reason, the furor forced Sam to resign—but also eventually set him on the road to Texas.

The Raven’s Bride

Elizabeth Crook (Doubleday, New York, 1991). Neither a historical romance nor a romantic history, The Raven’s Bride defies easy categorization; hence the long delay before its publication in paperback this month by Southern Methodist University Press. Examining, from the woman’s point of view, Sam Houston’s ill-fated first marriage to a Tennessee beauty, this well-written novel of the 1820’s combines historical accuracy with flights of fancy. Author Crook offers multiple excuses for the marriage’s demise—Sam’s extreme jealousy, Eliza’s accidental discovery of his plans to go to Texas, and both parties’ energetic premarital affairs—and her novel is perhaps the only book about Sam Houston containing a description of the great man’s genitals. But despite Crook’s careful research, the novel is almost anti-Sam, failing to convey his indisputable charm, and for all the title character’s fictional fleshing-out, the reader finds Eliza as cold as the author conjectures that Sam did.

I Do (Take Three)

After his first two marriages—the debacle with Eliza Allen and an on-again, off-again relationship with the Cherokee widow Tiana Rogers—Sam was determined that his third try be a charm. At 47, he married a 21-year-old Alabama belle, Margaret Moffette Lea. The union endured, but despite Sam’s protestations of love in hundreds of letters—“I cannot be happy but where you are”—he managed to live apart from her more than half of their 23-year marriage, frequently staying away eight or ten months at a time.

The Shadow Wife

After Sam was elected U.S. Senator in 1846, Margaret Houston shocked Washington by declining to accompany her husband to the nation’s capitol—for thirteen years. She reluctantly moved to Austin after Sam won the Texas governorship, but she disliked the strange city, the public scrutiny, and especially the Governor’s Mansion, which she found far too large and opulent after the modest quarters Sam had always provided for her.

Star of Destiny: The Private Life of Sam and Margaret Houston

Madge Thornall Roberts (University of North Texas Press, Denton, 1993). Written by a great-great-granddaughter, and thus somewhat lacking in the objectivity department, this tale of a marriage is based on the correspondence of Sam and Margaret Houston. But Roberts fails to note that their actions often contradicted their words. Margaret, for instance, was a confirmed homebody, yet Roberts reports that “Margaret’s dream of returning to Washington with her husband was shattered when she once again discovered she was pregnant.” The book does present an accurate and intriguing portrait of nineteenth-century life, however, and its best parts are the appendices, which include a financial breakdown of Margaret’s estate (“one Santa Anna Gold Snuff Box, $125.00”) as well as a selection of her syrupy poems (a verse of one encouraging Sam to resist Demon Rum runs, “Yes I would linger yet awhile/His lonely heart to cheer,/And break the artful tempter’s wile/That would his soul ensnare”). Her final paragraph on Sam’s death reads a lot like the equivalent passage in Marquis James’s biography.

The Honeymooners

Whatever their differences, Margaret and Sam found themselves in agreement on one issue: their often-expressed devotion to one another. Both dedicated to each other voluminous verses of the florid, overwrought doggerel of the day. Further proof took the form of eight children, the last of whom was born when Sam was 67. Margaret, generally a shy woman, once wrote her husband that when he returned home, “I shall be sitting, as in bygone days, on your lap, with my arms around your neck, the happiest, the most blest of wives” and later added coyly, “Many other arguments will suggest themselves to your mind.”

Yanked Away

Decried as a unionist (although Sam Junior promptly enlisted in the Confederate Army), Sam lived out the last two years of his life in relative isolation in Huntsville. Surrounded by family and friends, he died July 26, 1863, at age seventy. His last words—“Almost certainly apocryphal,” according to historian John Hoyt Williams—were “Texas! Texas! Margaret!” He left everything to his wife except for the sword he carried at San Jacinto, which he willed to Sam Junior. But the estate was so meager that it was months before Margaret could afford a marker for his grave.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Sam Houston