Every demagogue needs enablers to help him grab power and hold on to it. In Senator Joe McCarthy’s case, newly unveiled records suggest that his most generous benefactors had Texas postal codes.

That backing started just after McCarthy launched his jihad against communism in February 1950. The Wisconsin Republican had always had deep-pocketed donors from his home state, but now conservatives across the country were lining up to support the character assassination and fear-mongering that would turn his cause into a crusade and his name into an ism. Public reporting of political contributions wasn’t required then, so it has been impossible to get a feel for where that money came from—until now. The senator’s professional and personal files have been under lock and key for sixty years at his alma mater, Marquette University, but they were made available for the first time and exclusively to this author. And while they’re not an organized accounting, they suggest just how generous Lone Star State boosters were. The files include more records of donations from Texas than from any other state, and more correspondence with Texas donors than with benefactors in any state other than Wisconsin.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Texans sided with McCarthy during the fierce home-front battles of the Cold War. The roots of that alliance were planted as early as 1938, when the House of Representatives formed the Un-American Activities Committee and named as its chair Texas Democrat Martin Dies. The Dies Committee, as it was widely known, was supposed to devote equal attention to right-wing and left-wing subversives, but that never happened. From the start Dies’s preferred enemies were New Dealers and the Communist Party; the former, he insisted, were a Trojan horse for the latter. The tall blond Texan from Colorado City was McCarthy’s spiritual father, pioneering nearly all the techniques the Wisconsinite would use to ferret out pinkos and Reds. Dies loudly named names, hundreds of them, and coined the parlance of the anti-Communist movement by accusing politicians of being “soft” on Russia and “coddling” Commies. He filled 600 file cabinets with a million index cards of gossip on un-American goings-on, and listed 280 labor groups, 438 newspapers, and 640 organizations—including the Camp Fire Girls and the Boy Scouts—as possible Communist fronts.

Dies temporarily retired in 1945 and a year later McCarthy was elected to the Senate, a posting that would let him borrow many of the Texan’s files and all of his rhetorical flourishes. But Texans’ contributions to the McCarthy cause were more than a matter of spirit, style, and index cards. After McCarthy set himself up as Dies’s successor with his 1950 speech claiming that the State Department was infested with Soviet spies, Democratic senator Millard Tydings called his bluff. The Wisconsin senator, his Maryland colleague said, was a faker and his holy war was a mirage. Publicly humiliated, McCarthy vowed revenge. He got it by turning to his network of wealthy contributors from Oklahoma, Maine, Minnesota, and especially Texas, who all together contributed $75,000 ($800,000 in today’s terms) to John Marshall Butler’s successful campaign to defeat Tydings in his 1950 bid for reelection.

One contribution stood out when congressional investigators later probed McCarthy’s unorthodox and possibly illegal out-of-state blitzkrieg—from Texas oil magnate Clint Murchison. “Having watched the actions of Mr. Tydings and the Un-American Activities Committee, I decided that I could possibly be of some service to the citizens of the United States by going up into Maryland and defeat[ing] the gentleman in the coming election,” Murchison explained in a letter to conservative radio host Fulton Lewis Jr., a copy of which is preserved in the Marquette archives. Murchison gave $5,000 in his name and another $5,000 in his wife’s, neither of which were reported until after the election and both of which were made out not to Butler but to his campaign manager, Jon Jonkel, who later pleaded guilty to six charges of violating spending laws.

McCarthy’s toppling of a fellow senator didn’t go unnoticed back in Texas. Lyndon Johnson, the state’s junior senator and the Democrats’ whip, cautioned liberal Democrats that it would be unwise for them to go after McCarthy until he did something that offended conservatives, too. “I will not,” he explained “commit my party to some high-school debate on the subject, ‘Resolved that Communism is good for the United States,’ with my party taking [the] affirmative.” Syndicated columnist Drew Pearson suggested another reason LBJ was gun-shy: his Texas oilmen benefactors liked McCarthy and “Lyndon feared they might put a candidate in the race against him if he bucked McCarthy . . . it was this evasion that helped win for the senator from Texas the nickname of ‘lyin’-down’ Johnson.” (On other occasions Pearson used the more lyrical “lyin’-down Lyndon.”)

Back at McCarthy’s office, letters of support were pouring in from across Texas, sometimes accompanied by as much as $1,000 in cash. At home, meanwhile, the senator and his new bride got a $6,000 Cadillac as a gift from more than 350 grateful admirers, most from Texas. Or at least that’s the story McCarthy liked telling; in a more likely version advanced by one of his staffers, it was rich Texas businessmen who bought the car and, when McCarthy wrecked it by hitting a deer, quickly purchased a replacement.

The more power McCarthy amassed in Washington, the easier it was for him to count on money from supporters across the country—and particularly in Texas. None of his Lone Star State fans was more bullish than Murchison, who signaled his conservative politics by naming one of his firms American Liberty Oil. A World War I veteran, he owned one of the largest independent oil companies in the nation, along with major holdings in natural gas, banks, railroads, life insurance, and the distinguished New York book publisher Henry Holt. (His son, Clint Murchison, Jr., founded the Dallas Cowboys a decade later.) Murchison’s contribution to the anti-Tydings campaign was just the beginning of his generosity to McCarthy; he donated $30,000 to other campaigns the Wisconsinite backed, offered jobs to those McCarthy recommended, and let the senator use his private planes, swim naked in the pool at his Hotel del Charro in California, and urinate outside his cabana. “I sized [McCarthy] up as the best tool in sight to fight Communism . . . I’m for anybody who’ll root out the people who are trying to destroy the American system,” Murchison said, adding that those people included not just card-carrying Communists but “egg heads” and “longhairs.”

Two fellow Texas tycoons—Dallas’s H.L. Hunt and Houston’s Roy Cullen—were equally soft touches when it came to McCarthy. Hunt was said to be a billionaire in an age when there were very few, while in his heyday Cullen likely was the richest man in America. Both had heard and read about the Wisconsin senator’s anti-Communist evangelism. And each donated to the cause of dumping Tydings as well as to the efforts to unseat McCarthy’s other Senate nemeses, William Benton of Connecticut and Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. Like Murchison, Hunt and Cullen were unabashed in their defense of the old guard. Liberals, socialists, and Communists constituted the Mistaken, Hunt said, and they control “nearly all of the big money in the United States” and “can be spoken of with complete disapproval.” As for Cullen, author Bryan Burrough described him in The Big Rich as “a Faulkneresque figure in a white summer suit, a man who detested Communists, ‘pinkos,’ and especially Roosevelt, [and] who preferred ‘n—ers and spics’ and ‘New York Jews’ to know their place.” Cullen was the first of the big three to bring McCarthy to Texas, calling him “the greatest man in America” and saying, “I hope [he] keeps all the Communist spies running until they get to Moscow.”

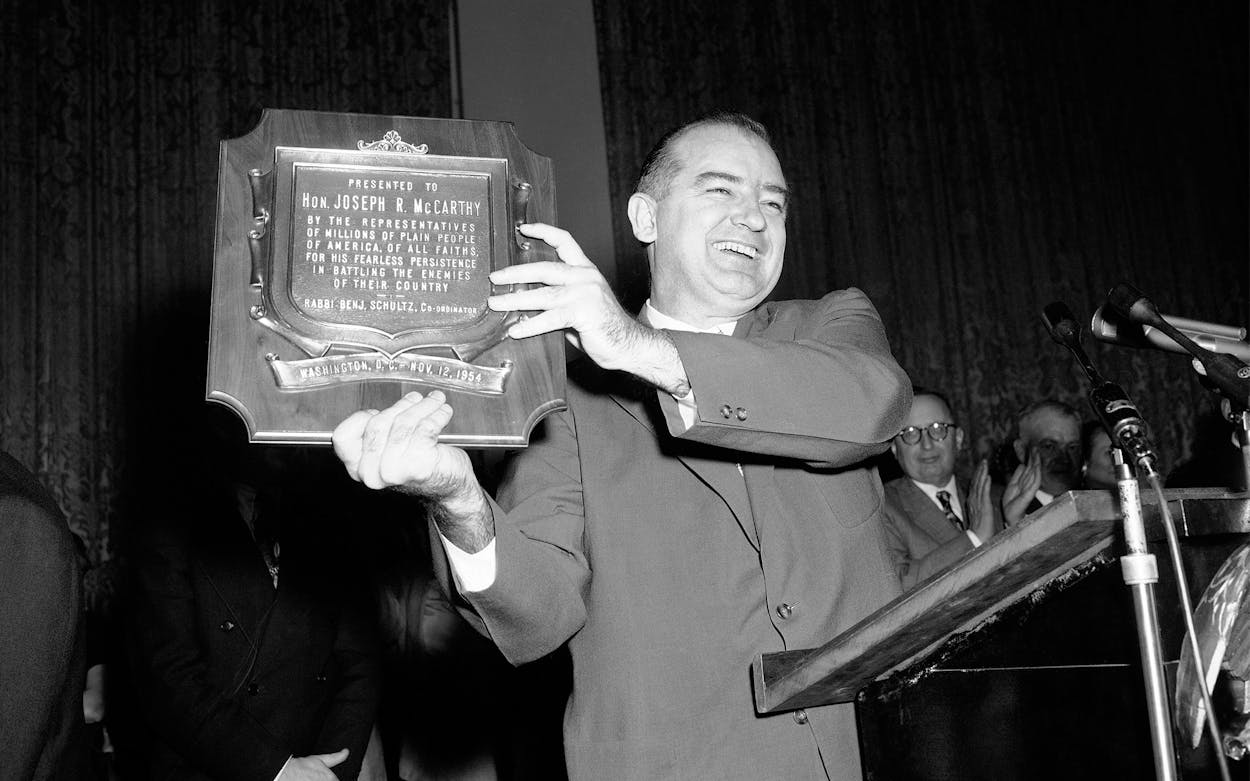

As of 1954, Texas Republicans had held just two $100-a-plate fundraising dinners, and one was to honor Joe McCarthy in February of that year, just as he leveling his charges of subversion within the U.S. Army. More than 1,000 supporters turned out in Dallas to hear his familiar “Twenty Years of Treason” speech, laying out the Roosevelt and Truman administrations’ alleged Commie coddling. Bankers and ranchers were there, along with cattlemen and oilmen, nearly all of whom were lifelong Democrats. The local press called McCarthy Texas’s Third Senator because he visited the state so often, and because he voted the Texas line on issues affecting oil, natural gas, and other matters vital to that state and sometimes contrary to the interests of his own state. What Texans liked even more, Fortune magazine concluded, was McCarthy’s combativeness: “The American system was being attacked by subversives; nowhere had that system reached a finer flowering than in Texas; nobody had more to lose should the attack succeed; McCarthy was determined it should not succeed. It seems to have been that simple.”

But McCarthy wasn’t truculent toward everyone. The Marquette papers show that he kept a list of people who “should receive first-class treatment in case they call,” and who his staff shouldn’t contact “without an okay first.” All the Texas oilmen were there, including Cullen and Hunt. A back-and-forth of letters shows he had even closer ties to Murchison, his most obliging banker. The magnate occasionally tried to tone McCarthy down, and to patch up his fractured relations with President Dwight Eisenhower. “If you have erred, the error can be laid to the intensity of purpose and not to the desire to hurt any innocent people,” Murchison wrote McCarthy. “I am trying to play the role of a good Samaritan who is trying to join the hands of two noble citizens. May God and others be with you, my boy, to the bitter end—including me. Sincerely, Clint.”

The senator’s office records show that he kept visiting Texas and touching base with his enablers right up until the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings that brought him down over accusations that he had pressured military brass to give favorable treatment to a former aide. Once the proceedings started and it became clear that making peace with the Army or the White House was impossible, Murchison offered McCarthy this advice: “If you keep on going as you presently have gone and do not get ‘snurly’ with [Army counsel Joseph] Welch, my opinion is that you are going to get back all of your public you have heretofore lost and possibly gain new admirers.”

But the senator couldn’t resist. Egged on by the ingenious Welch, McCarthy did get snurly and worse, coming across to a nationwide TV audience like a town rowdy. At the start of the hearings polls showed that an astounding 50 percent of Americans approved of the Red-baiting senator, but his support plummeted to 34 percent by the time the sessions wrapped up in June 1954. That gave his fellow senators the backbone to finally condemn their outlaw colleague. And while his Texas underwriters never lost their enthusiasm for McCarthyism, they quietly began to cut their ties to Senator McCarthy. The same May 1954 article in Fortune that documented McCarthy’s popularity among Texas businessmen noted that President Eisenhower’s recent questioning of McCarthy’s “ethics and competence” were taking a toll on the senator.

“A number of Texas businessmen,” the business magazine concluded, “began to have second thoughts about their ‘Third Senator.’”

This story is adapted from Larry Tye’s Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, July 7).

Correction: The original version of this story made an anachronistic reference to zip codes, which were not used until 1963. The article has been updated to refer to postal codes instead. And a photo caption misidentified Roy Cohn. Cohn is shown sitting to Senator McCarthy’s right, not his left.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Dallas