When I tell someone I’m a hobbyist forager, the responses range from shock to wonder, confusion, and suspicion. I tell them that this February, when Texas froze over and the power grid failed statewide, I felt weirdly at peace. I had a pantry filled with foraged staples: acorns, pecans, elderflower, juniper berries, and dried allium canadense, or wild garlic. I could walk out to the nearby parks and trails in the Hill Country to find more if absolutely necessary. As food insecurity rose, particularly among those in poverty or those who had lost work during the pandemic in my mixed-income neighborhood in San Antonio, my neighbors traded pantry items with me for brioche bread I had made largely from wild ingredients like acorn flour and elderflower sugar. Foraging is an ancient skill built out of survival necessity, but I only recently discovered its merits.

Foragers gather, hunt, or fish what they eat rather than buy their food from a grocery store or cultivate crops in a garden. These methods are not entirely mutually exclusive—I still visit my local H-E-B—but foraging is a way of life, a kind of commitment to self-sufficiency. I didn’t wake up one day and think, “I’m going to traipse around the woods and eat raw things.” The transition was more subtle. By its end, the outdoors exploded with possibility and fueled my confidence in the kitchen.

My foraging habit started after an encounter with a neighbor a couple of years before the pandemic, before I returned to my native Texas, when I was living in North Carolina. Her relative worked as a chef and forager, and I received an invitation to their Thanksgiving dinner based partly on my sad cooking stories. I personally took pride in my kitchen failures, because without trying there is no failing, but my neighbor was a seasoned homemaker and worried about my and my then-husband’s thinness. I accepted the invitation willingly.

The meal was unlike any I’d ever had. Most memorable out of the six courses were the roast heritage turkey; roast venison with wild orange, cranberry, raisin, and shallot sauce; and a wild mushroom and herb amaro. Each bite rippled with shocking flavor and depth. The chef had not only prepared everything by hand, but had hunted, gathered, preserved, and brewed the entire meal without visiting a grocery store. I knew the meal would be prepared by a professional, but I had assumed that “wild” would mean gamy or unrefined. I consumed a feast prepared by someone who had seen the eyes of their prey before death, who had followed creeks, rivers, and trails to find the best spot for harvesting wild mushrooms from the woods. I sat closer to the beginning and end of the food supply chain than ever, and I wanted to know more.

At first I sat on the sidelines, casually saving recipes and plant identification guides on Pinterest and imagining what I could make with wild food. But when grocery stores became dangerous, potentially dangerous, potentially teeming with the coronavirus, foraging began to sound like a safe haven. I signed up for a virtual foraging course and dived in. I learned about foraging ethics, an old but surprisingly complex set of considerations. What do you take and when? How much can you collect? Who has permission to take? Can you forage in national parks? Why do foraging laws exist, and who put them in place to keep whom from benefiting? I learned to question why it was so easy to rack up a large grocery bill of items individually wrapped in plastic packaging. I also learned about cleaning your foraging tools between harvesting each plant type to prevent spread of disease. The more I read, the more I began to see the environment around me as sensitive and interdependent on the health of everything that interacts with it. The more I observed, the more I felt challenged to participate in the life of the wild.

In April of last year, I found my first foraged ingredient among some tall grass. I recognized the floral bulbs and single, long, green stems. I pinched off a seeded piece of the bulb and confirmed my hunch in slow motion. It smelled like garlic, it looked like garlic—it was garlic! Back home, I found a recipe for Taiwanese scallion pancakes then added bits of the diced stem to the sesame seed oil dough. They were devoured for breakfast the next morning.

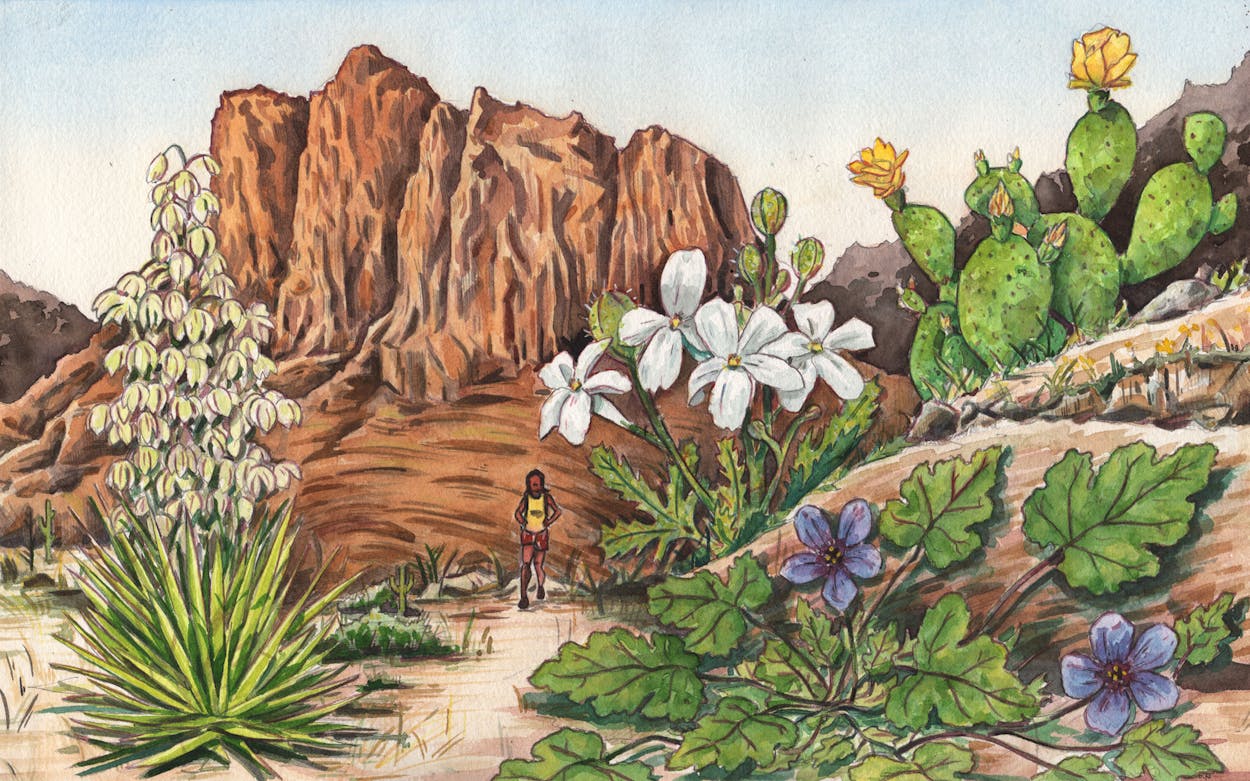

Next, I found a hedge of prickly pear cactus brimming with ripe, deep red fruit known as tunas. We picked them carefully and avoided the sharp pricks of the tiny glochid hairs. We made prickly pear sorbet and simple syrup. I was attaining some success.

A year after my online course, I found myself in Dripping Springs for a foraging class. Hill Country Texas is vastly different from the Sandhills of North Carolina, and since wildlife is largely location dependent, I knew I needed Texan guidance. I was lucky to find it for free at the local library with Mark “Merriwether” Vorderbruggen, a PhD chemist by training, who now runs a popular foraging site and hub of educational information on plant identification and general foraging knowledge.

We started off on Zoom, and Vorderbruggen occupied the tiny corner of my phone screen wearing rectangular frame glasses, a long beard that dipped past the V-neck of his shirt, a mustache, and most distinctively, a mohawk. With the youthful enthusiasm of a kindergarten teacher and the edgy exterior of a heavy metal enthusiast, he lauded the benefits of agarita, bull nettle, dayflower, filaree, goldenrod, passion vine, prickly pear cactus, purslane, purple sage, shepherd’s purse, sumac, Turk’s cap, and yucca. All wild edible or medicinal plants. Then he transitioned from Zoom professor to field guide. I closed my screen and donned my walking shoes.

“To get started we’re actually going to look at a plant right there,” Vorderbruggen said, and pointed near my feet where I sat on a limestone bench. He took out a steel-bladed pocket knife with a wood handle and dug up a small sprig of green.

“This is pony’s foot,” he said, and passed around the small, round-leafed plant to the group of about ten. He said the pony’s foot could be eaten fresh but also goes well in a kind of microgreens sauerkraut. But, he warned, the ones he just picked were within dog-leash distance, so he wouldn’t recommend eating them. Some of the children in the crowd munched away anyway.

By the end of the class I had filled my notebook with details on more than twenty plants, several of which I would have loved to have in my stores during the freezing temperatures and power outages in February. In times of greater economic hardship, Vorderbruggen said, he receives more interest in his classes. Since 2008 he has been busier than ever. While I don’t like the idea of people forced to rely on wild food, I can’t say I mind increased awareness of the power and abundance in our own backyards.

Foraging is a process of learning, unlearning, and relearning. I’m learning to use all of my senses to evaluate the proper shape, texture, color, and scent of a potential harvest. I’m unlearning the overreliance on shelf-bought kitchen produce. I’m relearning how to connect with the younger side of me that used to dig around in the dirt.

Little by little, I’ve increased my food knowledge and cooking skills from Hamburger Helper to field fresh. I’ve made mulberry syrup, acorn flour muffins, and herbal teas from plants I’ve foraged. I snuck wild ingredients into staple meals like scrambled eggs and watched my family gobble them down. I follow social media accounts like Alexis Nikole’s Black Forager and Chefs Wild for educational posts on cooking and foraging. I join in on Vorderbruggen’s Facebook Live chats and take notes on the community’s experiences. In these small pockets I’ve gained the knowledge to stock my pantry with 30 percent foraged goods.

On a Hill Country trail, I spot a thick clump of juniper, low and heavy with berries. I know now that their hazy exterior is a result of wild yeast and that they can be used to make gin or sourdough. They drop from the branch willingly with a tickle of my fingers. I gather what feels like a pint, and claim my spot on the food chain, one step at a time.

- More About:

- San Antonio