As Governor Greg Abbott spoke from his podium at a press conference on Tuesday, pallets full of personal protective equipment, a rare commodity in the age of COVID-19, were piled high behind him. Abbott proudly announced that Texas would soon be able to supply one million masks per week to health care providers on the frontlines of the coronavirus outbreak, and then he tried to reassure constituents.

But during the conference, Abbott again declined to order a statewide shelter-in-place—something health care professionals, state legislators, and local officials have been clamoring for as COVID-19 spreads throughout the state. All the while, he acknowledged that the lesser restrictions he implemented last week do not appear to be working. “It is clear to me that we may not be achieving the level of compliance that is needed,” he said. “We will continue to evaluate based on all the data whether there needs to be heightened standards and stricter enforcement.”

While other governors are taking aggressive actions to slow the spread of the coronavirus, Abbott has instead favored a wait-and-see approach that leaves the most effective tactics up to local leaders. He’s taken a series of smaller measures, like requesting health insurers waive copayments and deductibles for testing and temporarily suspending evictions, aimed at supporting an already overburdened health care system and mitigating the outbreak’s economic impact.

But that approach alone might not be tenable. Testing data lags far behind where it needs to be for the governor to accurately assess the true scope of the pandemic in Texas, and the number of confirmed cases in the state is rapidly increasing. The CEO of the Texas Hospital Association, which represents 450 hospitals and health care systems statewide, warned that more than 200,000 Texans could require hospitalization by mid-May, and hospitals would be overwhelmed as early as mid-April.

For the past month, Abbott has consistently been a step behind other states, both in taking strong statewide action to slow the spread of COVID-19 and in ramping up testing for the virus. The longer the state’s response continues to move at its current hesitant pace, the more disastrous the results could be in the months to come.

State of Emergency Order and Restaurant and Bar Closures

On February 29, the state of Washington became the first to declare a state of emergency over COVID-19. Emergency declarations at the state level typically allow governors to devote more money to state agencies fighting the outbreak, waive certain regulations that might otherwise slow the state’s response, and to streamline administrative procedures normally required to purchase supplies. In some cases, as in Washington, they also grant the governor legal authority to implement broad restrictions on public movement, a crucial step to stop community spread of the virus.

A day after Washington, Florida declared its own state of emergency, and many states soon followed shortly after confirming their first cases. Louisiana, for example, declared a state of emergency on March 11, two days after identifying its first case. New Mexico did too, a day after reporting its first positive test. By the time Abbott declared a state of disaster on March 13, 26 states had already done so, and there were at least fifty cases of COVID-19 in Texas.

“From the very beginning, our number one objective has been to implement preventative strategies that build on our state’s existing public health capabilities so that no matter how this situation unfolds, Texas will be ready,” Abbott said in a press release announcing the disaster declaration. “The State of Texas is prepared, and we continue to take proactive measures.”

Six days passed before Abbott, on March 19, ordered the closure of restaurants and bars, banned gatherings of ten or more people, and closed schools, as many other states had done days earlier. The executive orders came only after local officials essentially begged Abbott to mandate statewide closures during a conference call the day before, and after nearly one hundred cases, and three COVID-related deaths, had been confirmed in Texas.

Since the restrictions announced on March 19, Abbott has not issued any orders aimed at further restricting public movement, even as the number of confirmed cases in Texas continues to grow at a rapid rate. As of Thursday, the number of COVID-19 cases in Texas exceeded 1,400 and at least 17 people here have died, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University.

John Wittman, a spokesman for Abbott, did not respond to Texas Monthly’s questions about the governor’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Shelter-in-Place Order

Twenty-one governors—including those in California, New York, and neighbors New Mexico, Louisiana, and Oklahoma—have implemented strict shelter-in-place orders requiring most residents to stay indoors with various exceptions. Such orders are designed to slow the outbreak so that health care providers, with limited resources, do not get overwhelmed.

Statistical models by the Imperial College of London suggest if a statewide shelter-in-place were in effect for three months, fewer than 5,000 people in Texas would die.

But Abbott has explicitly left the decision to shelter-in-place up to local officials, resulting in a disjointed patchwork of restrictions across the state. For example, officials in Harris County, the most populous county in the state, ordered residents to stay at home until April 3 at the earliest. But more than 500,000 residents in neighboring Montgomery County are under no such mandatory restrictions. “I’m just going to ask citizens of Montgomery County to continue to self-regulate, and we’re going to get through this at some point,” Montgomery County Judge Mark Keough told the Houston Chronicle.

“Unless there’s some standardization of what these restrictive measures are, it is going to be hard to stop [the virus],” said Dr. Diana Cervantes, the director of the master of public health in epidemiology program at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. “Ultimately if you really want to go all the way with this, you have to go all the way, because if not, you’re just going to continue having this spread.”

Abbott has indicated that he may consider a statewide shelter-in-place order later on, but first he wants to see whether some of the lesser measures he took last week will have an impact on curbing the spread of the coronavirus. And he’s concerned about implementing restrictions on public movement in areas of the state that so far have not reported a large number of confirmed COVID-19 cases.

“I am governor of 254 counties in the state of Texas,” Abbott said Sunday. “What may be right for places like the large urban areas may not be right at this time for more than two hundred counties that have zero cases of COVID-19.”

At the time Abbott made those comments, there were confirmed cases of COVID-19 in 45 Texas counties. On Thursday, Johns Hopkins University’s database reported cases in 152 counties (the state’s tracking of cases, which does not include presumed positive cases, lists 92 counties). Hockley County, outside Lubbock, has five known cases among its population of 23,000. Matagorda County, population 36,000, has nine known cases. Neither counties have mandated shelter-in-place orders.

“If they even have a few cases in a rural county, because their health care system is so much more resource-limited, it would be a huge issue,” Cervantes said. “There’s definitely transmission that is going on in these rural counties. But because right now, the way we’re quantifying the spread of this coronavirus is by looking at just confirmed cases, we’re not capturing all that.”

Testing

Perhaps the biggest problem with Abbott’s plodding, pragmatic approach is that it appears to be heavily informed by testing data that is simply inadequate to assess the spread of COVID-19 throughout the state.

When Greg Abbott said on March 16 that “everyone who needs a COVID-19 test will be able to get a COVID-19 test,” only 220 people had been tested in Texas by state and CDC labs.

In the days since, people across Texas have been denied access to COVID-19 tests, despite seemingly meeting the state’s strict criteria to receive one (the testing requirements prioritize health care providers and emergency first responders, seniors, and people showing symptoms).

To date, according to Texas Department of State Health Services data, only 21,424 tests have been administered over the duration of the outbreak, with the vast majority of those tests—87 percent—processed by private labs. For comparison, the state of New York processed 8,000 tests in a single night last week.

On Sunday, Abbott said the lack of testing was a result of Texas not having enough medical supplies to safely perform the tests. He urged the federal government to ramp up production of these supplies and assured suppliers that, “We have money to pay for anybody that can sell personal protective equipment to us, and we will cut you a check on the spot.”

The shortage of testing supplies is a challenge shared by every other state—Abbott said in a press conference Tuesday that Texas is competing with other state governments, and even with the federal government, in a race to buy medical supplies. But it seems to be hindering Texas more so than similar size states. New York’s first confirmed coronavirus case was reported on March 1, and by Wednesday it had already administered more than 103,000 tests. Texas also lags far behind California (77,800 tests as of Wednesday) and Florida (28,644 tests as of Friday).

Abbott said in a press conference Thursday that Texas is lagging behind other states because the federal government has prioritized places where the outbreak is particularly bad, like New York and Washington, when allocating supplies needed for testing. But testing rates are higher in states where the COVID-19 outbreak appears to be less severe, too.

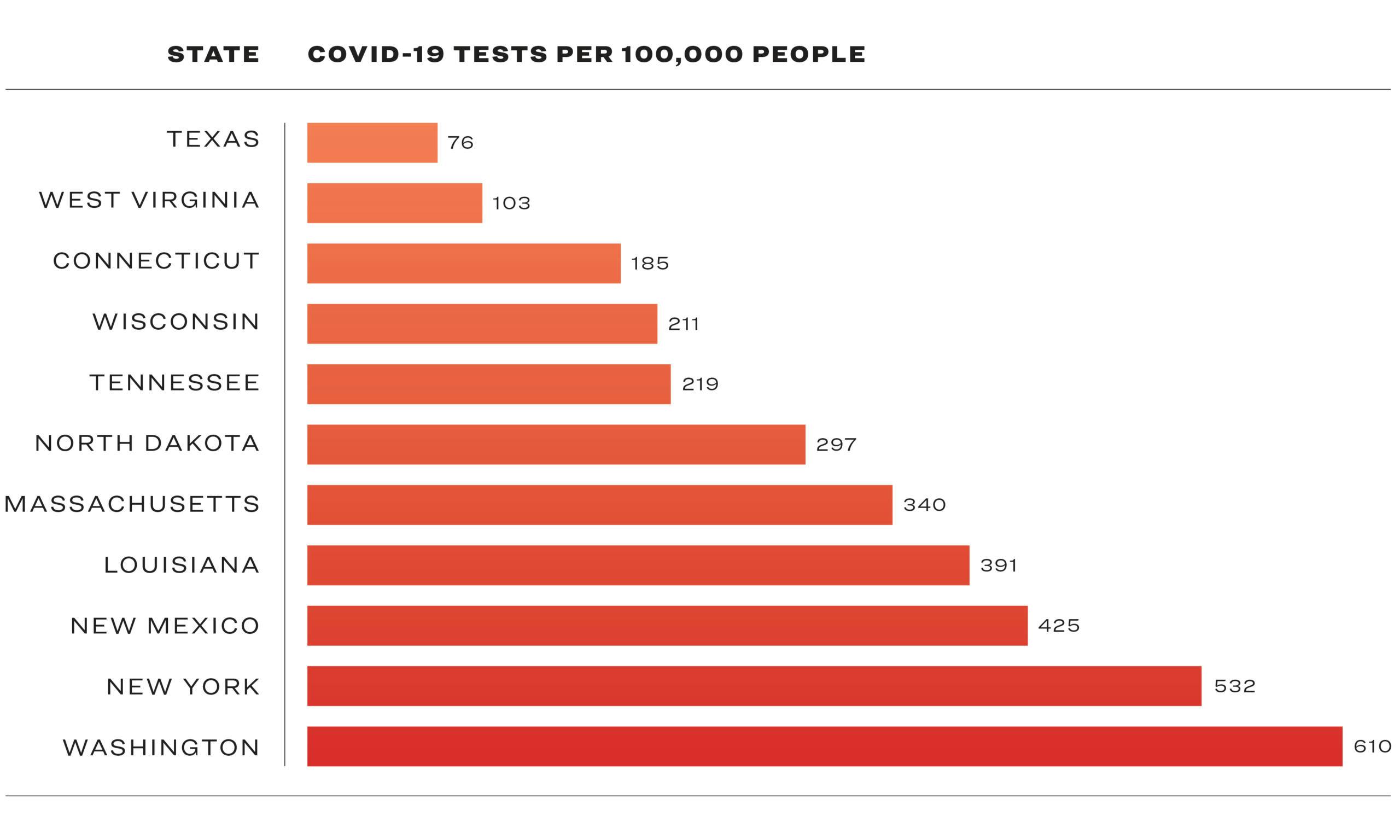

In Wisconsin, where ten deaths have been confirmed in connection to COVID-19, per Johns Hopkins data accessed Friday afternoon, there have been 211 tests administered per 100,000 people. The state of Tennessee has processed 219 tests per 100,000 people and reported three deaths. North Dakota has reported no deaths and has conducted 297 tests per 100,000 people. But in Texas, the testing rate is just 76 people per 100,000.

It’s unclear exactly how the state’s current testing capacity compares with the demand for tests. Department of State Health Services spokesman Chris Van Deusen will not say how many requests DSHS has received seeking the state-required pre-approval for public labs to test a patient. The state has also refused to release records that could shed light on exactly how many testing requests it’s receiving. In response to an open records request filed by Texas Monthly, Van Deusen refused to release redacted copies of forms required to submit COVID-19 test samples to DSHS, citing a provision in the state health code that says “reports, records, and information relating to cases or suspected cases of diseases or health conditions are not public information.” DSHS is also refusing to release shipping tracking numbers that accompany each specimen sent to the state lab for testing.

While Abbott now seems to be leaving the brunt of the pandemic response up to local officials, his hands-off approach is a departure from his previous tendency to meddle in local affairs: overriding cities’s regulations on fracking, ride-share companies, and even local tree removal. He has also consistently fought local ordinances that would guarantee paid sick leave for all workers—protections that would likely make it much easier for Texans to follow some of his latest orders in response to the pandemic.

“We don’t need people that are sick coming to work,” Abbott said in his press conference on March 13. He was seated closely between DSHS commissioner John Hellerstedt and Nim Kidd, chief of the Texas Division of Emergency Management, with ten more officials standing shoulder-to-shoulder behind him, despite the CDC’s warnings to avoid large gatherings and maintain social distancing standards.

A reporter later asked whether he’d been tested for COVID-19. “No,” Abbott said. He then jokingly coughed into his hand, and smiled.

As we cover the novel coronavirus in Texas, we’d like to hear from you. Share with us your tips or stories about how the outbreak is affecting you. Email us at [email-hidden].

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Health

- Greg Abbott