This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I am living the dream. The bullet train is rolling through the French countryside at 168 miles per hour. It is a misty January morning, and even though we are north of Montreal by latitude, the pastures between Paris and Lyon are as verdant as the Brazos River bottoms in May. I have no sense of traveling at a high velocity—until a jolt of disturbed air portends the coming of a northbound train. The blur is past us in less than three seconds. Otherwise, we glide along the welded rails without a single lurch, vibration, or clickety-clack. There is ample time to take in the pastoral landscape as it slips by—the placid brook beyond the tracks, spanned here and there by wooden footbridges; the herd of sheep that takes no notice of our intrusion; the steeples on distant hills that are as prominent in rural France as water towers are in rural Texas; the vineyards at Mâcon, the fog over the river Saône, the medieval abbey at Cluny.

It is so civilized. In front of me, on a table that separates two rows of facing seats, is a plate that will not long be stacked high with croissants. Another plate has packages of fromage—Montrachet, Gouda, Beaufort, Camembert, and Brie. A disposable coffee dripper is filling my cup. I lean back and extend my legs with no worry of disturbing the person across from me. Is it too early, I wonder, for some vin blanc?

The dream is that the bullet train can be transplanted to Texas, right down to the croissants. By the year 2000, if everything goes according to plan, we will be riding French TGV trains—the initials stand for train à grande vitesse, or “train of great speed”—between Dallas and Houston, with a Dallas–San Antonio leg soon to follow and perhaps a San Antonio–Houston link in the future. The thought is irresistible. No more cramped middle seats on Boeing 737’s, no more long waits in check-in lines, no more pushing and shoving at the gate to be first in your boarding group, no more seat belts, no more peanuts, no more worrying whether Hobby will be fogged in, no more air turbulence, no more banal messages from pilots that you can’t hear anyway because of the engine noise.

But the bullet train has never gotten on the fast track in Texas. Texas TGV, the company that beat out a German-backed rival for the Texas franchise in 1991, is under constant attack: for overstating its ridership projections, for understating its costs, for seeking public subsidies after promising it would not, for missing a deadline to raise $167 million in equity, and for failing to address the fears of Texans along the proposed routes that the fenced railroad right-of-way would amount to a Berlin Wall through rural Texas. In towns like Seguin, Franklin, and Westphalia, opponents of the bullet train have banded together to form DERAIL (Demanding Ethics, Responsibility, and Accountability in Legislation). They are backing a proposal to dismantle the Texas High-Speed Rail Authority and revoke Texas TGV’s franchise.

The fate of the bullet train may not have the urgency of issues like education and crime, but it does lie at the heart of a recurring debate in modern American politics: When is it proper for government to impose its social preferences on private activity? In abortions? In hiring practices? How about transportation? The Clinton administration proposes to commit a billion dollars to bullet trains over the next five years in funding and tax breaks for high-speed rail projects and in developing magnetic levitation technology. This is part of its much-touted program to rebuild American infrastructure. Yet, in this country and especially in this state, bullet trains would duplicate an existing transportation system. They are slower than airplanes and more expensive, requiring total grade separation, crossings for farmers and animals, and concrete ties for the roadbed. Texas TGV must make a capital investment of $6.8 billion to serve 4 city pairs (Dallas-Houston, Dallas–San Antonio, Dallas-Austin, and San Antonio–Austin). Southwest Airlines, the bullet train’s principal rival for passengers, has invested $2.2 billion in its planes and other assets, with which it serves 514 city pairs.

The cost of high-speed rail is so enormous that success can only come through the sort of government support—not just financial but also philosophical—that the Clinton administration has embraced. Hard cash is not the only way the federal government can show its preference for rail; it can, as governments do in Europe, raise the cost of traveling by automobile (by taxing gasoline) and by airplane (by taxing passengers). It is not by chance that rail is the dominant means of transportation in France, where gasoline is $4 a gallon and state-owned airlines charge high domestic fares. Federal support for bullet trains masquerades as support for infrastructure, but it is really support for the way the government thinks we ought to travel instead of the way we have chosen to.

The case for the bullet train in Texas is social, not economic. Bullet trains use less energy, create less pollution, and make passengers more comfortable than airplanes. “The train is sociable and safe” reads a flyer put out by the French national railway company. “In a world in which these qualities are valued, it surely offers the best alternative form of transport.” In America, however, the market has always valued speed and price above all else.

Most of the criticism of the bullet train has been directed at the likelihood that it will fail and somehow leave the State of Texas holding the bag for the costs. This is the wrong issue: The financing is structured so that the state can’t possibly be held liable. The real concern ought not to be that the bullet train will fail but that it will succeed.

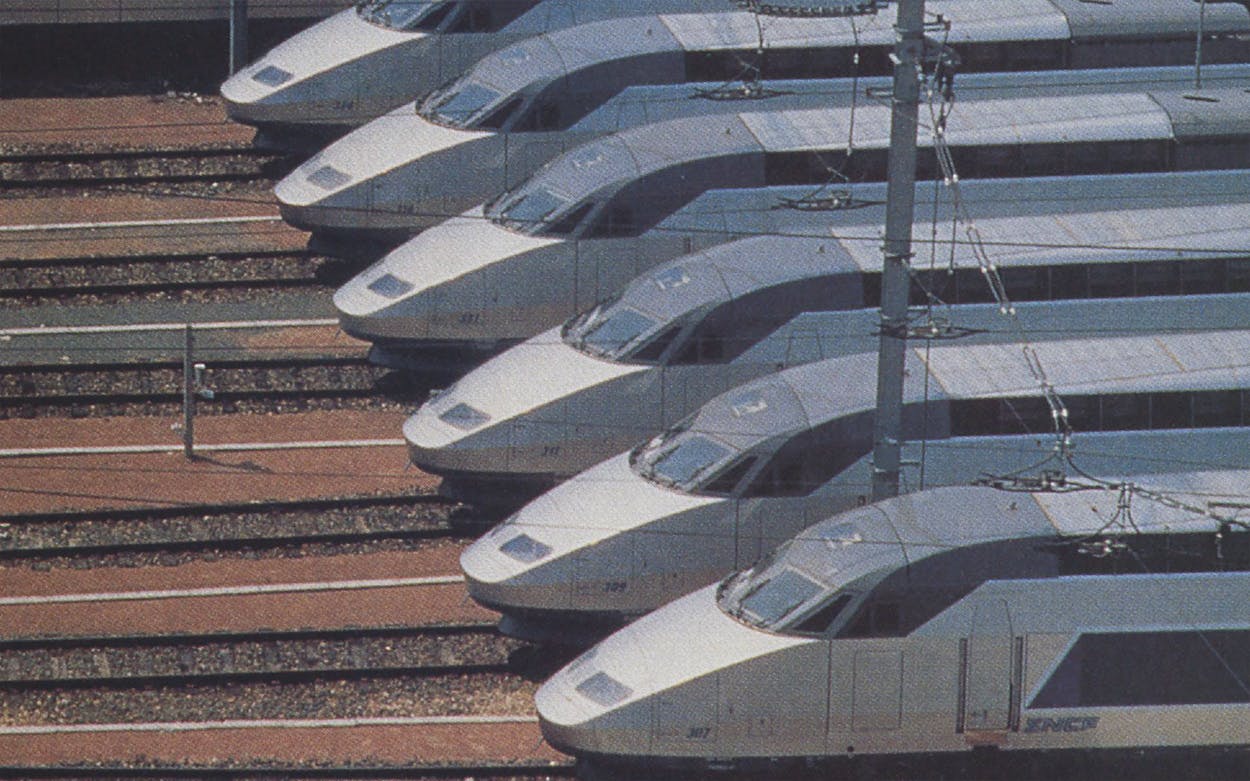

I can think of better places to spend a day in Paris than the TGV maintenance yard, but here we are—four Texas lobbyists for the French and Canadian companies that manufacture the bullet train (who have coached me not to call the bullet train “the bullet train,” since in the high-speed rail business, the phrase specifically describes the Japanese version), a Canadian TV crew, and myself. We are here to learn what makes the TGV the world’s best train. On the east side of the yard is the main track of the TGV Atlantique line to Bordeaux. Every ten minutes or so, trains pass by with nothing more than a soft whoosh, as if they were coasting.

Indeed, we soon learn that they probably are coasting. One power car in the maintenance yard has a diagonal blue stripe painted across its sloping nose on which “513.5 km” is printed in white. This engine, hauling a shortened load on a practice run, holds the world speed record for a train—320 miles per hour. The Texas TGV will have a top speed of 200 miles per hour and will make the trip between Houston and Dallas in 90 minutes—35 minutes longer than by air. It could go much faster than its top operating speed but only at an unacceptably high cost in increased energy consumption and wear and tear on the track. To save energy the TGV coasts 40 percent of the time between Lyon and Paris. If the train is a minute ahead of schedule when it is 40 kilometers (25 miles) from the station, the engineer can cut the power and coast into the Gare de Lyon on time.

Inside a maintenance barn, cars have been lifted hydraulically off the wheel assembly, known as a bogie. The bogie is the guts of TGV technology, the device that makes the ride smooth and eliminates swaying and jerking. In the United States, a train car has its own set of wheel trucks at each end. But a TGV bogie spans two cars, providing one set of wheels for each. The cars do not have American-style couplers but are joined at the bogie, much as the trailer on an eighteen-wheeler connects to the cab. In fact, our French and Canadian hosts refer to passenger coaches as “trailers.” Once the cars are linked together, the train operates as a unit and goes through maintenance as a unit. If more passenger capacity is needed, the French add complete train sets—usually eight trailers with a power car at each end—rather than more cars.

The lobbyists listen dutifully to the engineering details of the TGV. But they are looking for something that might win the support of the average legislator back home, and bogies are not a likely candidate.

“How many people work at a place like this?” asks one. Eight hundred and thirty is the answer.

“Gotta go see the unions. They’ll love the thing.”

We walk past stacks of boxes filled with seat cushions. A guide explains that they are on their way to be cleaned.

“There’s economic development I never thought about,” says another member of the group. “Cleaning. I bet these seats get mighty dirty.”

“We need a list of subcontractors,” says a female member of the lobby team. “That’s how we got some lottery votes.”

At the end of the long tour, the TV crew films an interview with Gordon “Doc” Arnold, a former legislator from Terrell. Canada is considering a bullet train, and Arnold represents Bombardier, a Montreal manufacturer that has a stake in Texas TGV. “What is the political opposition to the bullet train?” a questioner asks.

“All the opposition is lack of knowledge,” Arnold says. “Once you’ve seen the TGV, once you’ve ridden it, once you’ve seen how it’s built, the objections disappear.”

“How will you finance it?”

“When our ridership study is complete, we believe investors will be attracted. I believe you’ll see the train operating in Texas by the year 2000. We want to be first.”

“Why?”

“Because we’re Texan.”

Verne John has seen the TGV. He has ridden it. He has seen how it’s built. But his objections haven’t disappeared.

A stocky man with dark curly hair and an earnest, good-natured air, John is an air conditioning technician in Franklin, a small town on U.S. 79 north of Bryan. He was part of a group of DERAIL members brought to France by Bombardier and another large shareholder in Texas TGV, GEC Alsthom, a French company that also makes the bullet train. The hosts hoped to demonstrate that the TGV had not destroyed rural life along the route: The tracks could curve and didn’t have to go in a straight line through whatever stood in their way, the noise didn’t disturb the animals, and the route included overpasses and culverts for farmers and animals to cross the tracks safely.

The cost of high-speed rail is so enormous that success can only come through some sort of government support.

John had made the trip armed with a Radio Shack decibel meter. He found that the noise of the train was comparable to that of a jet in flight. That French farmers tolerated it didn’t surprise him. “Noise is relative to perception,” he says. “France is a crowded country. There’s a lot of background noise, even in the rural areas. We don’t have that kind of background noise here.”

Verne and his wife, Gilda, are sitting in the living room of the rambling frame house they bought a year ago. From time to time our conversation is punctuated with the loud wail of a Union Pacific freight. They tell of going to a meeting in Hearne, one of more than three dozen held around the state, that was supposed to address citizens’ environmental concerns. Instead, they found what they describe as “a pep rally for the train”—lots of promotion but no awareness of rural issues.

“It was the done-deal aspect that got everyone,” says Mary Barreda, a consulting geologist from Anderson who has driven more than seventy miles to sit in on our discussion. “We were treated so contemptuously.” Citizens asked representatives of Morrison Knudsen, the Idaho-based construction company that was the driving force behind Texas TGV before Bombardier and Alsthom got involved, whether small chunks of farm acreage would be isolated by the tracks. “They told us that French farmers had just traded land with farmers on the other side of the tracks,” she says. “Can you imagine telling Texans to trade land? You can barely get two farmers to agree who’ll work on the fence. You would get farmers saying, ‘I cleared the brush off that land. I picked up the rocks. That guy hasn’t taken care of his land. I’m not about to give up my land for his.’ ”

“The culverts they want to build are ten by ten,” says Verne John. “A cab tractor needs twelve and a half feet of height to get through. Hay equipment needs at least sixteen feet of width.”

The opposition to the bullet train has coalesced in DERAIL, which was started by two men in Westphalia, a tiny settlement east of Temple, where a possible train route threatened a historic church and cemetery. “This is better than a soap opera,” says Barreda. “People go to Austin to dig out information. We write and fax each other.” What they have found has only reinforced their suspicions about a done deal.

Before awarding the franchise, the Texas High-Speed Rail Authority hired financial and engineering consultants to evaluate the rival bidders’ claims. Then they ignored their own advisers. Here is a small sample of the negative barrage from the consultants: “TGV’s ridership forecasts appear to be on the high side”; “Capital cost estimates appear to be low”; “Although the State will have no obligation to repay the debt, de facto moral and market obligations probably do exist”; “The cost for electrification should be increased by about $500 million.”

The DERAILers studied the Texas High-Speed Rail Act and saw that it granted a monopoly that would be virtually unregulated. They read the proceedings of the High-Speed Rail Authority and learned that the hearings examiner was a registered lobbyist for the City of Fort Worth—which both applicants amended their plans to serve. They read the testimony of Morrison Knudsen’s chairman, who promised the High-Speed Rail Authority, “Texas TGV does not ask for state financing or public subsidies.” Then they read the testimony of another Morrison Knudsen official, who told Congress that high-speed rail projects with insufficient revenues “will have to be augmented with some form of public assistance.” They even found an obscure proposal by a University of Texas transportation researcher for a high-speed freeway between Dallas and Houston to be built by the year 2020. An accompanying sketch showed twelve lanes of traffic with—aha!—a bullet train in the center. Was the TGV line just a stalking-horse for a mammoth freeway?

“The average businessman in Navasota knows this is a scam,” Barreda says. “It’s not going to work.”

But even if it did work, DERAIL would still be against it. The bullet train is a classic rural-versus-urban confrontation. All the social and economic benefits go to the cities at the end of the line; all the social and economic costs, from lower property values to more noise, are borne by the people in the country. The most outspoken DERAILers are not farmers but feedstore owners, CPAs, and other self-employed people who live in the country by choice.

The Johns decided to move close to Franklin three years ago, after Verne was laid off in Houston. An image haunts him from his years in the city: a big house that used to be in the country until the Hardy Toll Road went through the back yard. “I was so shocked,” he says. “I told Gilda, ‘You can’t believe what we did to these people.’

“You don’t own anything in this world. You just get to use it until somebody bigger comes along and takes it from you.”

Before Texas TGV can take anything from anybody, it must find investors. Although the major participants—Morrison Knudsen, GEC Alsthom, and Bombardier—are paying for the operation of the High-Speed Rail Authority (the use of state funds is prohibited by law) and for an environmental study that is badly overbudget, the big bucks will ultimately be other people’s money. Even the initial equity of $167 million will largely come from borrowed funds.

The debt payments will be crushing: $788 million a year starting in 2003. Add to that annual operating costs in the neighborhood of $200 million a year, and the bullet train will require around $1 billion a year in revenues just to turn a profit—ten times what Southwest Airlines now grosses from local passengers on the same routes. Based on Texas TGV’s financing plan, here is what must occur in order for TGV to make money:

• American Airlines must cancel all flights from Houston, San Antonio, and Austin to DFW Airport and contract with Texas TGV to bring passengers by train. The ridership projections are absolutely dependent upon this contingency. It is not totally farfetched, since most airlines, Southwest being the exception, don’t make money on short-haul flights. The only trouble is that American’s chairman, Robert Crandall, is on record as doubting that the bullet train can attract enough passengers to be profitable.

• Congress must remove limitations on issuing tax-exempt bonds for high-speed rail projects. But Congress refused to do so just last year. Maybe the Clinton administration can persuade them.

• The market for Dallas-Houston and Dallas–San Antonio travel must grow by 35 percent between 1991 and 2001. The bullet train must capture more than half of that market, including automobile travel.

• It must find investors willing to bet on a project that requires massive refinancing and 19 to 23 years to make a profit. (This is the estimate of Harriett Stanley of the Massachusetts-based Hadley Group, financial consultants to the High-Speed Rail Authority.)

• Finally—and these are my calculations, not Texas TGV’s—the bullet train needs close to a 100 percent occupancy rate year-round to make money. (With 34 round trips a day on two lines and a capacity of 317 passengers per train, an average fare of $70 would generate a maximum of $1.1 billion a year.)

James Gerber has an explanation for everything. Texas TGV’s financial director is the perfect numbers man: average height, average weight, average build, average face, average voice with an average, calm tone that seldom varies, nothing to divert attention from his soothing reassurances. What about the criticism from consultants? “A number of these advisers sometimes rendered opinions in areas where they do not have expertise, such as ridership.” What about American Airlines? “We’ve retained their operations research subsidiary to look into integrating TGV into airline systems.” What about the reluctance of Congress to ease the rules on high-speed rail bonds? “We don’t need as much tax-free debt as we thought.” What about the fear that the state’s credit rating may suffer if TGV goes bankrupt and Texas doesn’t pay off the bonds issued in its name? “We’ll insure payment with letters of credit from banks. It’s designed to be no risk to the State of Texas.”

“Growth and inflation will make this project work,” he says. “Texas is planning on growth. This won’t hurt Southwest Airlines. Only 12 percent of Southwest’s traffic is on these corridors.”

“But won’t the bullet train hurt Southwest in smaller Texas cities?” I ask. Southwest says that if it loses traffic into Dallas, it won’t have the volume of business necessary to serve places like Amarillo, Lubbock, and Midland.

For once, James Gerber’s response is out of character. “The tears are flowing down my face,” he says.

Southwest Airlines’ headquarters, on the west edge of Love Field in Dallas, is as nondescript as the Wonder Bread bakery next door. Chairman Herb Kelleher planned it that way. “I told the architects, ‘I don’t want a statement,’ ” he says. “If a thousand people a day drive by and only one notices we’re here, that’s fine.” Inside, the decor is as plain as the block exterior. The art is pictures of airplanes and framed pages from old corporate reports. In the executive suite, there is a bluebonnet painting with a Southwest jet in the sky and a collection of pottery that could have come from the local flea market.

It is the ultimate misfortune of the Texas TGV partners that they must operate on turf that currently belongs to the only airline with costs so low that it can thrive on short-haul flights. (When I asked an American Airlines analyst about a possible deal between American and the bullet train, the response, part disdain and part grudging admiration, was, “Texas already has a train. It’s called Southwest Airlines. It drops off passengers, loads up, and moves on.”)

The Paris-Lyon bullet train line has virtually replaced air travel between the cities and has greatly increased total traffic in the corridor. But Dallas-Houston is not Paris-Lyon. Both French cities have extensive metro systems that feed into train stations. In Texas, however, air travel is as dominant as rail is in France. The ratio of air passengers to population in the Dallas-Houston corridor is 543 out of every 1,000. No other corridor in America is even close, not even New York–Washington, which is second with 333 out of 1,000. The logical inference is that there is not a lot of new business to be won.

“My basic question is, What’s the need?” Kelleher says. He is standing up, waving a cigarette, and grinning from the shoulders up. When he laughs, the physical energy bursts onto his face, carving wrinkles and seams that didn’t previously exist. He unleashes a series of one-liners aimed at Texas TGV, punctuating each one with a jab of the cigarette.

“Those population estimates—they would have to rip off every condom in Texas to get that many people.”

“It’s not a business right now. It’s bond salesmen, contractors, and lobbyists.”

The man is impossible to interview. He won’t sit down and he won’t stop talking.

“We don’t fit the pattern. We’re not supposed to make money on short-haul flights. It’s like the economist who said, ‘There’s something wrong here: It works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory.’ ”

In a rare serious moment, Kelleher reiterates what he has said before: He’s not against the bullet train; he’s just against subsidies. He doesn’t mind competition; he just doesn’t want to compete with the government.

Texas TGV can play this game too. James Gerber says that the test of the bullet train’s ridership potential will come in the marketplace. If a current ridership study comes back with favorable numbers, if the financing plan is sound, the bullet train will get investors. If not, it won’t. Let the market decide. As for subsidies, well, the airlines have them too. Southwest will avoid paying property taxes by locating its new Albuquerque reservations center on leased public land. Love Field was built as a military airfield. The government taxes passengers to support the air-traffic control system. All Texas TGV asks is a level playing field. But the issue isn’t really who gets what subsidy; it’s the magnitude of the subsidy the bullet train will almost certainly require—and whether it is necessary at all.

Back at the airport, I looked at the pack pressing toward the boarding gate and wondered what it would be like to have the option of going by train. Sure, I’d take it. So would most people. Make the train equivalent in price, and the train will win.

But what if it can’t be equivalent in price? What if the debt load is so extensive that the train can’t operate at a profit? Morrison Knudsen will have made its money by building the line. Alsthom and Bombardier will have made their money by building the trains. Will they let Texas TGV bleed their profits away? Or will they shut it down? And what then? Will the tracks be allowed to rust and the train sets to gather dust? Or will the government come along and buy the train for Amtrak—What a bargain! It’s already there!—just to keep the dream alive?

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas