The Permian Basin has a way of making you feel small. The sheer scale of its geography, the never-ending horizon, that big sky. Traveling through this dusty, mostly flat, nearly treeless region of West Texas, one gets a sense of being at sea, adrift in an expanse of red dirt, the monotony broken occasionally by shin oak, sand dunes, pump jacks, the steel spikes of rig derricks, columns of flame from natural gas flares, and, more recently, the long, slender blades of wind turbines. Even for those of us who grew up there, such enormity can be overwhelming, almost numbing. It can make it hard to see the place.

Fortunately, we can now see the Permian Basin through a singular lens—that of Dan Winters, who has worked for the past two decades out of a studio in Driftwood, near Austin, and is internationally celebrated for his portraiture. Winters has shot astronauts and presidents, sports icons and Hollywood royalty. He’s been hugged by Mister Rogers and stabbed by Hunter S. Thompson (dinner fork, back of the hand). But until recently he had never focused his attention and his camera on the Permian.

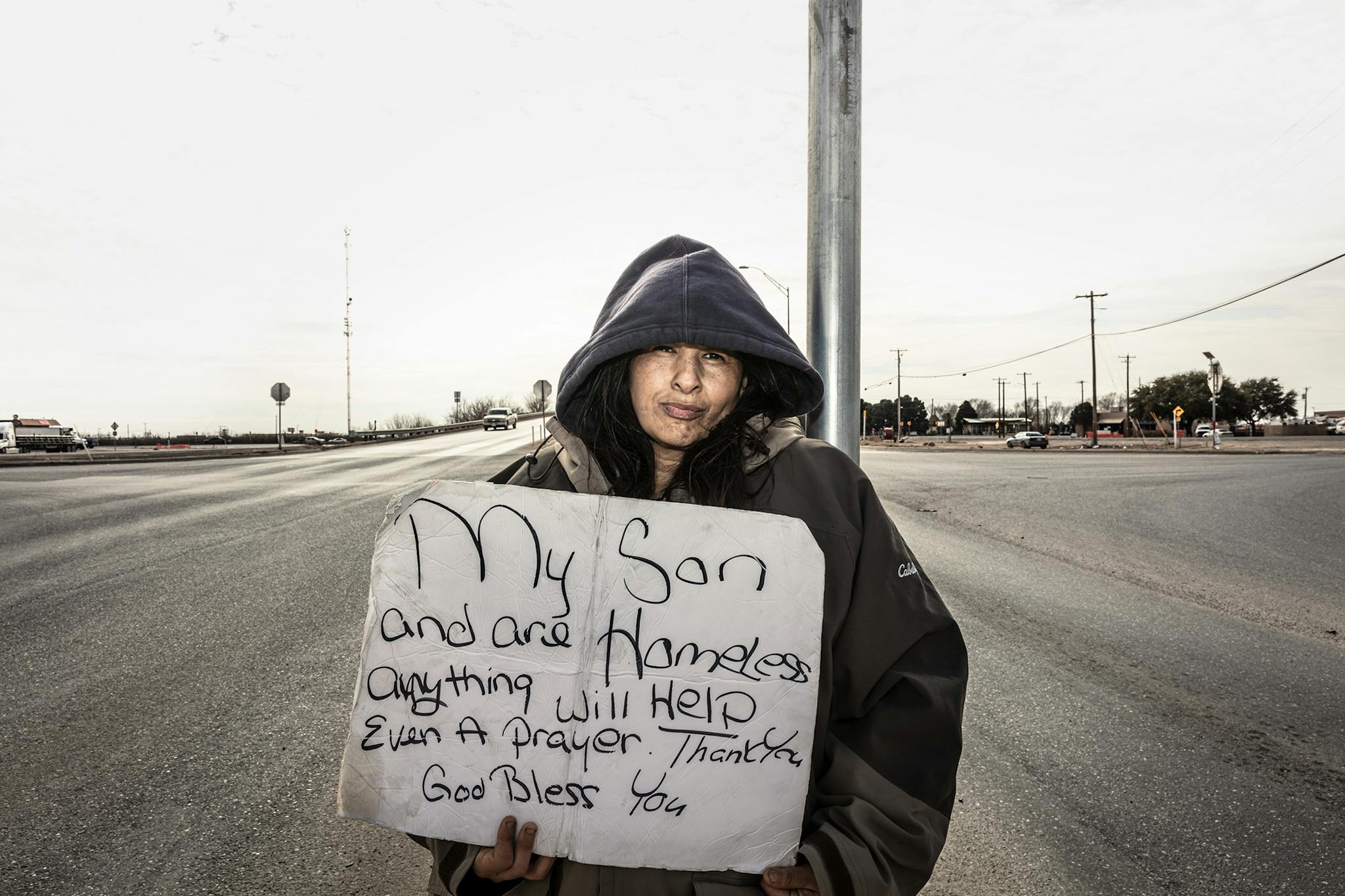

Beginning last October, Winters spent fifteen days over four separate trips crisscrossing most of the seventeen West Texas counties that span the Permian. “As expansive as West Texas is, you feel a little bit insignificant,” Winters said. “And I felt that a lot. We were traveling huge distances to get maybe one picture. You start to respect the place for its sheer volume. There’s also a hardness and evidence of hard living. It’s not glamorous by any stretch of the imagination.”

Winters picked a consequential moment to capture the region. No place was spared the chaos of the pandemic, but the Permian’s economy was devastated more than most. As the virus spread, an unprecedented oil boom quickly turned into a historic bust. In April of last year, the unthinkable happened: the price of oil briefly went negative for the first time ever, as supply outstripped demand and producers had to scramble to find emergency storage for their surplus crude. As the rig count plummeted, thousands of itinerant workers were laid off, leaving the man camps they’d been living in, two to a room, suddenly empty. The highways, which had been dangerously overrun with tankers just a few weeks earlier, were packed with U-Hauls and RVs retreating to homes across Texas and as far afield as North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and even Canada.

But this unparalleled turn of events was not what Winters was chasing. His gift is noticing: the sharply drawn geometry of a railroad stop, the surprisingly beautiful color gradations of a wastewater pit, the lone beam of light illuminating a glass bottle inside a shuttered cafe. The land feels domineering or simply indifferent. Spend a while in the Permian, and you’ll realize that the desert, given enough time, will reclaim whatever we’ve laid upon it. That temporality can be witnessed in Winters’s photographic impressions: flecking paint, mangled trucks, rusting oil-field equipment. Small details of a vast place, inviting us to look closely. To really see.

This article originally appeared in the June 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Nothing Beside Remains.” Subscribe today.