This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On a warm summer day in 1983, Mayor Kathy Whitmire called a news conference to announce a big change in the way Houston worked. She had just completed a capital improvement plan—something that had taken a year of painstaking planning and public meetings. For as long as anyone could remember, Houston had never had a set program for new streets, storm drains, parks, and buildings. Voters would approve bond sales for projects, but the city was not required to use the money for what the voters wanted; funds for a neighborhood fire station might go to build a storm sewer in another part of town. Decisions on which projects to fund were often made behind closed doors at the public works department. Whitmire’s revolutionary plan tied bond money to projects; when Houstonians voted to build a new fire station, they would get a new fire station.

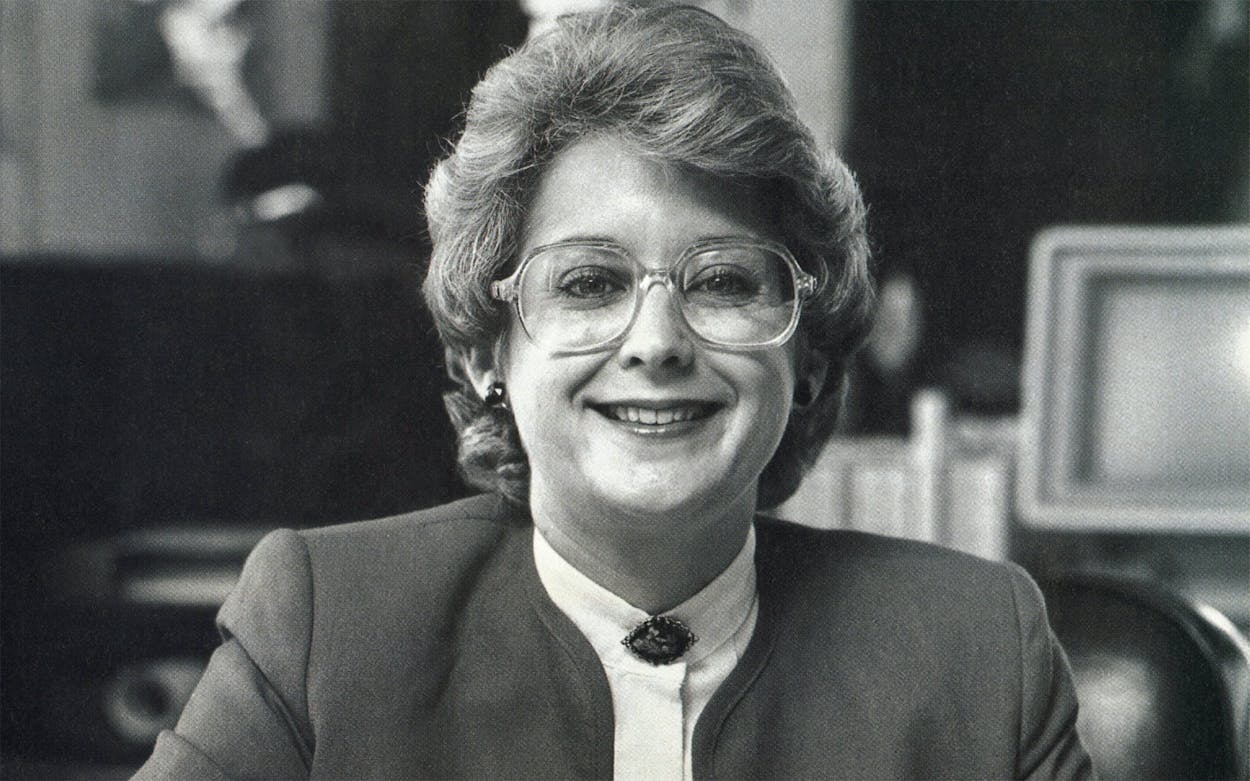

The mayor, wearing her customary bow tie, was clearly pleased with herself. But the city hall reporters gathered in front of her were not. Meeting with Whitmire had been an unpleasant task too many times. She had been openly hostile to several reporters and seemed to resent their questions. Now there was tension in the air. It was clear that no one was disposed to celebrate the mayor’s accomplishment. After a few perfunctory questions, the conference was over. The historic capital improvement plan sank from public view with only scant mention in the press.

The news conference, which took place on the eve of Whitmire’s election to a second term, typifies the problems that threaten her bid for a third. Her achievements—and they are considerable—are largely forgotten or ignored; her political bungling—and it too is considerable—is getting all the attention. Although Whitmire, with characteristic doggedness, has gone about tackling the issues that brought her into office, like efficient management and businesslike government, times have changed. When she was elected four years ago, Houston was at the height of the oil boom, and the city was growing so fast that the insiders and good ol’ boys who dominated city hall couldn’t keep the potholes filled and the garbage trucks running. Within six months the public was focusing on problems more pressing than efficient government: rising unemployment, a tumbling economy, overdependence on oil, and what the mayor was going to do about them. Her answer—more efficiency, more businesslike government—was not what they wanted to hear. Whitmire grew defensive and aloof; after all, she was doing what she was elected to do, wasn’t she? She had a knack for alienating friends and supporters. Before long, people began referring to the Kathy Problem. Her record on nuts-and-bolts issues slipped into the background, while her bad public image and political ineptitude came to the forefront. The result is that a mayor who has probably kept more campaign promises than any of her predecessors has at best an even chance of winning a third term in November.

The A Team

The cornerstone of Whitmire’s philosophy of government is to appoint strong leaders. Her directors have applied themselves to the problems of reorganization and reform, and whatever Houston’s economic woes, it is indisputable that the major departments at city hall work better since Whitmire took office. The improvement is evident in the biggest and most important department, public works. It laid down 30 miles of permanent paving in fiscal 1985 (only 10 miles were laid in 1981, Mayor Jim McConn’s last year), 178 miles of topping and overlay (up from a stunning 11 miles in 1981), and approximately 800 miles of resurfacing (up from McConn’s 200). The department says that complaints about potholes have dropped significantly.

Garbage collection was so bad under McConn that when a strike was settled, wags joked that no one could tell the difference. Whitmire has added a preventive maintenance program, the absence of which in the McConn era meant that on any given day, half the trucks were out of service. Under McConn 30 per cent of the water in the mains was lost because of leaks. Today that has been reduced to 15 per cent. To check land subsidence caused by excessive pumping of groundwater, the city has been relying less on wells and more on surface water from reservoirs.

The Houston police began the eighties with a reputation as one of the worst departments in the United States, and not just because of its shoot-first-ask-questions-later attitude toward minorities. Like every other city department, the police suffered from years of neglect, inadequate funding, poor leadership, and no planning. The force was ridiculously small for a city the size of Houston, badly trained, and ill equipped. Whitmire’s appointment of Lee Brown as police chief was significant not so much because he was black but because he was good, and Whitmire has backed him up. The force is the only department to survive the recession with relatively generous funding. The result is that Houston now has about 25 per cent more officers on the street and about a thousand more employees in the department as a whole. But crime has been going down in most major categories, and it has dropped 25 per cent downtown. A recent FBI report showed that of America’s six largest cities, Houston now has the lowest violent-crime rate.

Morale is still a problem (isn’t police morale always a problem?); Whitmire has come under heavy attack for proposing low pay raises and benefits. Brown is unpopular in some quarters for his strict disciplinary tactics, and Whitmire, who started out with the support of some union leaders, has run into inevitable criticism for reforming the state civil service law that police and firemen’s unions have regarded as their sacred preserve. The change allows Brown to select his own assistant chiefs, ensuring that he has a loyal team at the top of the chain of command. But despite the complaints, there can be little doubt that the public is better off today than it was in 1981.

Besides improving public safety, Whitmire’s administration has developed an outdoor cafe ordinance, helped promote the arts of the city at home and across the country, and doubled the city’s park space through the acquisition of 10,500-acre Cullen Park, which will be the largest city-managed park in America.

Traffic, always a central issue in Houston, is largely beyond anybody’s control, although Whitmire has avoided such gaffes as McConn’s decision to eliminate funding for a Galleria-area traffic plan. A new setback ordinance, backed by Whitmire, will prevent the recurrence of concrete canyons where buildings begin so close to the right-of-way that streets cannot possibly be widened. The mayor did appoint the majority of the board that hired Alan Kiepper as head of the much-maligned Metropolitan Transit Authority, and she helped persuade Kiepper to take the job, so she deserves a portion of the credit for the turnaround at MTA. Buses arrive on schedule 96 per cent of the time, up from 39 per cent in 1981. The number of miles buses travel between mechanical problems has increased from 513 to 6211. Passenger trips are up 20 per cent, and the cost per mile of operation is down from $5.54 to $3.32. There are hundreds of new bus shelters and thousands of new bus-stop markers with information on them (replacing the forlorn metal sticks with painted tips hidden beside the road), and buses are cleaned daily. The Metro board, having learned its lesson from the rail plan, now holds numerous town hall meetings to keep in touch with the public.

Out of the many department directors she has carefully chosen over the years, only a few have had to be replaced. One may have injured her politically: Robert Swartout, the chief of the fire department. Swartout and Whitmire, it turned out, did not agree on how to run the fire department. He left in a huff, and she refused to release the letter of explanation he wrote. “Her insistence that she didn’t know why he quit, her refusal to release the letter, and her reaction afterward were inexplicable,” says George Greanias, a council member who was once one of Whitmire’s closest allies. “Her strong points with the public are her honesty and integrity. It affected her adversely with the public. She made a bad situation worse.”

Although Houston has come a long way since Jim McConn, Whitmire has plenty of critics, and some say that the city is far from being an efficient operation. “Her main idea is to sit on her managers very hard and give them less and less,” says Greanias. “Simply cutting expenses does not automatically make more efficiency.” There are also complaints that the grass isn’t being cut, that dangerous buildings aren’t being torn down, that health and other inspections aren’t being made, and that the legal department is ignoring the enforcement of deed restrictions.

More for Less

Whitmire came into the mayor’s office promising better services for less money. She also promised reform, which meant wresting control of city government from the crowd of developers, engineers, architects, contractors, builders, and consultants that under Jim McConn had been allowed to run wild. In office she ran into the eternal problem of the reformer: it is hard to win praise, and easy to win enemies, merely by neutralizing negatives. Her achievements have been substantial but unglamorous. She has reorganized, for the better, the way things are done in Houston, but the only people who seem to care are those who have lost influence at city hall. Their eagerness to get her hands off the machinery that turns out permits, inspections, and contracts should never be underestimated.

Recall, for a moment, how things worked in the McConn era. Insiders made millions on deals like the cable TV franchise, which was carved up and the pieces handed out to the mayor’s friends and supporters. There was no bidding for professional services like engineering; contracts were political plums. The stench of corruption filled the air; the city purchasing director pleaded guilty to extorting money from city contractors.

Whitmire has changed all that by taking politics out of the awarding of contracts. She instituted a computerized system by which all candidates eligible to bid on contracts are considered objectively. The computer spread the city’s largesse among friends and enemies alike. Unfortunately for her, the new system satisfied no one. Outsiders who had backed her found to their dismay that the computer was giving the same old firms most of the business. Moreover, she denied her friends and supporters special access to her office. Her enemies, meanwhile, were hardly mollified by their reduced, if still substantial, share of city business.

Another important fiscal reform—and one that did win her some points—was to bring capital projects in on time and within budget. Whitmire achieved that by assigning construction management teams to the projects. The shining example is the George R. Brown Convention Center on the east side of downtown, which had not gotten past the wishful thinking stage because of legal and financial problems. Having fought a successful referendum battle to get the project going again, Whitmire assigned a management group to work with architects and engineers and bring the cost of the center down from $127 million to $104 million. Construction began in February and is expected to be completed on schedule. Even Whitmire’s critics concede she was a “major spark plug” for the project.

Sewage, once such a plague that federal and state officials slapped a moratorium on development in most of the city because treatment plants were overloaded, has all but disappeared as an issue. A 200-million-gallon treatment plant that opened in 1983 vastly increased the city’s capacity, and though the project was begun before Whitmire took office, she can take credit for its completion a year ahead of schedule. Pollution in Buffalo Bayou has been reduced by 90 per cent. Most major sewer system improvements are 75 per cent federally funded, but Houston has been garnering an additional 10 per cent for some projects because of innovative programs and exemplary planning. Last year the city won an unanticipated $33 million from the Environmental Protection Agency because other Texas cities weren’t prepared to spend it and Houston was.

In her first campaign, Whitmire emphasized that she would practice the sound fiscal policies she had preached as city controller. She has cleaned up some of the worst problems, such as the practice of allowing employees to accumulate unused sick leave and then cash it in upon retirement at current salary. Whitmire championed a change in state law that will sharply reduce Houston’s potential liability (it exceeded $120 million) in future years. But the oil slump has caused tax revenues to fall consistently short of expectations and kept the city budget in a continual state of crisis. During that first campaign Whitmire pledged to pass her budgets through the council on time, something that rarely occurred in the seventies. She did it in 1982, but it hasn’t happened since. The mayor and council have bickered and haggled, raised fees and fines to cover costs, and cut spending to the bone to balance the budget.

Reviews are mixed. John Privett, president of Tax Research Association, a business-sponsored tax-watch group, says that Whitmire has contained the budget and brought employees’ relatively high salaries more in line with those of other cities. “Very, very tough,” says Privett.

Others, like city councilman George Greanias, are less impressed. Greanias has grown so disenchanted with the mayor’s fiscal policies that he contemplated running for mayor himself. By refusing to do what Greanias calls “balancing the budget honestly”—by either raising taxes or cutting services—Whitmire has run afoul not only of Greanias but also of Lance Lalor, who holds Whitmire’s old job of controller. Lalor accuses the mayor of raiding rainy-day accounts such as surplus and reserve funds to pay current operating expenses. Whitmire, Lalor says, has increased the city’s debt to the point that of the ten largest cities in the United States, only New York and Philadelphia have a higher debt per capita.

During Whitmire’s second term Houston lost its once-sacrosanct AAA bond rating. Whether Whitmire’s fiscal policies contributed to the fall to AA, as Greanias believes, or whether the drop solely reflects the city’s uncertain economic condition, as her defenders insist, is a matter of conjecture. But the bond raters could hardly have been happy that Whitmire dipped into the emergency debt service fund to help balance the budget. The fund is supposed to hold enough cash to pay a year’s worth of interest on the city’s bond debt, thus assuring bond holders of payment in case of catastrophe.

Though the mayor now concedes that a tax increase may be down the road, she has stood firm against raising taxes, reasoning that low taxes give Houston an edge over other cities competing for businesses and that citizens can’t afford to pay higher taxes during a recession.

Coming to Order

If records were all that counted in politics, Kathy Whitmire would be a shoo-in for a third term and Bill Clements would still be governor. But personality is as much a part of governing as performance is. With the right style one can disarm the opposition and charm the public; Ronald Reagan is said to be Teflon-coated—criticism doesn’t stick to him. With the wrong style one gets credit for nothing and blame for everything. Kathy Whitmire is coated with molasses. Compromise, negotiation, and just plain getting along in the political world are not Whitmire’s strong points. “You always disagree with Ms. Whitmire,” says Lester Tyra, president of the Houston Professional Fire Fighters Association. “You’re always wrong, and she’s always right. She has no understanding of the politics, the political aspect of the job, the give-and-take type of thing. She’s a very cold individual. She has very little understanding of the word ‘tact.’ ”

Tommy Britt, president of the Houston Police Patrolmen’s Union, is equally blunt. “Her attitude is, If you don’t like it, lump it. She can be very petty, very vindictive.” Whitmire’s problems with Tyra and Britt are symptomatic of her larger political troubles. As adversaries in one of her major crusades—reforming the notoriously pro-union state civil service law that regulates the hiring, firing, and benefits for firemen and police—they were never going to be her greatest admirers. But Whitmire’s negotiating style turned them into implacable, unforgiving enemies. Tyra says that she called him “immoral, unethical, and unreasonable”; Britt says simply, “We think she was lying to us the whole time.”

Before Whitmire got involved, there actually seemed to be a chance that things might work out smoothly. Britt met with city attorney Jerry Smith regularly to negotiate changes. Smith, Britt assumed, was representing the city, but eventually it became obvious that the mayor “in her typical style” had not informed the city council members that Smith was negotiating on their behalf, says Britt. When it came time for Smith and Britt to present the compromises to the council, people’s “egos got involved”—they felt they’d been cut out of negotiations—and the unions had to hammer out the compromises with the council all over again. “It caused some bad feelings,” says Britt, whose union had been willing enough to negotiate. Jerry Smith, it seemed, wasn’t speaking for anyone. The mayor’s council allies didn’t support the compromises, and even the mayor’s chief of police objected to some of them. “It created the suspicion that she had not really dealt with us in good faith.”

The situation did not improve in Austin, where the Legislature had the final say over whether to change the law. Having already angered the union leaders with her attitude, Whitmire then proceeded to enrage powerful supporters of her reform proposals at the Houston Chamber of Commerce with her tactics. Desperate to get a bill passed, she made concessions to unions that the chamber refused to support. The original sponsors of her bill refused to go along with her and found a way to block the new proposal. After some intense last-minute negotiating, the bill passed in a form that was more to the chamber’s liking. But Whitmire no longer was able to claim political credit for it.

Whitmire’s relations with the city council began auspiciously enough, but over the years her indelicate and uncompromising approach has eroded her support there. Six of the fourteen council members meet weekly for breakfast to discuss the many things they don’t love about Whitmire: her temper, her grudges, her crude political skills. “She has not enjoyed the best of a healthy working relationship with council members,” says Councilman Rodney Ellis. “I have noticed a tendency to try to improve relations, but her attempts tend to be somewhat erratic. At times she tries harder, and other times she doesn’t.” She started holding breakfast meetings with council members about a year ago, Ellis says, but then stopped.

Whitmire has been accused of ignoring political etiquette; she fails to inform council members of upcoming agenda items, neglects to count her support before throwing controversial issues up for a vote, and creates ill will over small matters—restricting keys to the city, for instance. Many members, even neutral ones, have been irritated when she seems to be taking credit for programs initiated or pushed by the council, such as charging developers for the right to hook up to future sewage treatment plants.

The Kathy Problem comes down to this: she doesn’t know how to make a deal. And in politics, especially Houston politics, knowing how to make a deal is vital. Houston has been built by, and usually is run by, people to whom making deals is second nature. Kathy doesn’t fit in, and trying to deal with her drives the dealmakers crazy. They constantly bring up such incidents as the legislative negotiations over a bill that would have hurt Houston’s ability to regulate billboards. Houston’s power brokers like the city’s strict billboard ordinance, which they think will give Houston an edge in attracting industry. They had the legislation bottled up until Kathy got involved—on their side. Actually, all Whitmire did was bring along a councilwoman to the negotiations. But the councilwoman was a novice to Austin who questioned the integrity of the bill’s sponsor, a no-no in close-knit legislative circles. The power brokers were forced to compromise, and they blamed Whitmire for introducing a wild card into the game.

Of all her mistakes, none has been more costly than her support of the gay rights referendum last January, which went down by four to one in a futile political fracas. Once again the problem was not really substance but style. A skilled dealmaker would have worked behind the scenes to avoid the confrontation, arguing that Houston didn’t need the divisiveness and bad national publicity in the middle of an economic slump. But Whitmire pushed the ordinance. “It was one of the greatest, most ill-premised, damaging-to-everybody plans ever conceived,” says Houston Post political columnist Tom Kennedy. “It did nothing for gays, mobilized people who are against gays, and put on the spot people who are in the middle. People like to think their leaders have a hand on the pulse of the community.”

The gay rights episode also drove a wedge between Whitmire and the good-government Republicans who had helped elect her to office. “We asked her not to get out front on that,” says Thad Hutcheson, an active Republican and a civic leader who worked closely with the mayor on campaign and economic issues until the January referendum. Whitmire indicated to members of the chamber of commerce that she wouldn’t, Hutcheson recalls. Subsequently Clintine Cashion, who is now in charge of Whitmire’s reelection campaign, was in the forefront in support of the referendum. Hutcheson says the mayor and her staff became so preoccupied with the issue that in January, when Hutcheson brought the chairman of the board of Swiss Air to the mayor’s office to talk about obtaining landing rights in Houston, one of the mayor’s top aides immediately steered the conversation onto the topic of the referendum. “And this man had flown all the way from Zurich,” says Hutcheson.

Later Hutcheson, who opposed the referendum and considered it neither a conservative nor a liberal matter—“It’s a family matter that becomes emotional when it gets into your neighborhood,” he says—brought Whitmire to a breakfast club group and described its members to her as younger, forward-thinking, progressive business people. “She thought a minute and said, ‘I’m surprised someone like you would identify with a progressive group.’ ” Seeking his endorsement, Whitmire recently called Hutcheson—who still says, “She’s got many good qualities”—to ask why he was so put off by her.

Also hanging over Whitmire is a statement she made years ago that attracting new jobs and industry to Houston was the responsibility of the chamber of commerce, not the mayor. “I feel she overlooks the business-getting aspect of the job in favor of political issues,” says developer Costa Kaldis, a former Whitmire supporter now active in the Louie Welch campaign and a former member of Whitmire’s Industrial Revenue Bond Board. He says he found her economic development staff lacking in competence. “I don’t know any businessman who’s putting wholehearted support behind her. She’s someone who does not really trust the business community. Do you see one good businessman on her staff?”

“I’m hurting,” says Kaldis. “Half my apartments are empty. My office buildings are empty. We need new leadership. We need to get back on an even keel.”

Whitmire has done more to stimulate economic growth than most give her credit for. She “busted a gut,” says one who has worked closely with her, to try to win a Navy home port for the battleship Wisconsin in the Houston-Galveston area. (It went to Corpus Christi.) For several years she has been laying the groundwork to bid for the summer Olympic Games, and next summer the city will host the National Sports Festival for U.S. Olympic athletes. Houston is finally taking advantage of tax-exempt financing for development that creates jobs in economically deprived areas. And the mayor, working with the recently formed Houston Economic Development Council (HEDC), has traveled to Europe, Washington, D.C., and New York to promote Houston. “She has markedly improved,” says Andrew Rudnick, executive vice president of the council. “She’s a real asset to the HEDC in that regard. She’s more comfortable with the job, more at ease with it.”

The political backrooms of Houston have always harbored the notion that Kathy Whitmire was a transitional mayor, an awkward, sharp-tongued temporary housekeeper who was setting things in order for the visionary leader to come. But managing a house as large and in such constant need of repair as Houston is no temporary job. For all her political fumbling, Whitmire has done a lot to bring some order to a chaotic city. But if she can’t get her own house in order, no one is going to care.

Susan Chadwick is a freelance writer who lives in Houston.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston