After a busy legislative session in Austin, Travis Clardy was ready for a lazy Saturday morning. It was mid-June, and the Republican state representative was finally back home in Nacogdoches, sipping coffee on the balcony of his downtown loft and watching his constituents amble about El Camino Real de los Tejas, a.k.a. Main Street, the central artery of the East Texas city. He had all but forgotten that one of his bills, regarding occupational licensing, remained unsigned on Governor Greg Abbott’s desk. Traditionally, the governor’s approval is automatic for minor proposals such as his that pass with overwhelming bipartisan support.

Then Clardy’s phone began to ring. A staffer for the governor was on the line, telling him Abbott was going to veto the representative’s bill, which would’ve made continuing education programs for state-certified fire alarm technicians mandatory rather than voluntary. The governor’s staffer explained that the bill, in Abbott’s estimation, presented an unjustified obstacle to maintaining an occupational license. But those qualms, Clardy said, could’ve been fixed in a matter of minutes during the session. “If that had been a concern,” he recalled asking, “why am I hearing about this now, after he’s already signed the veto?” The answer became clear to Clardy later, when Abbott published a missive explaining his decision. In the second paragraph of the letter, Abbott wrote: “This bill can be reconsidered at a future special session only after education freedom is passed.”

Clardy understood what Abbott was saying: if lawmakers didn’t support the governor’s priorities, he wouldn’t back theirs. “This isn’t between the lines,” Clardy told me recently. “I mean, he says it: ‘I’m going to kill [the bill] and you got no hope of moving the bill unless you flip-flop on your vote.’ ” Clardy soon found that he wasn’t alone. The governor rejected a whopping 77 bills this year, according to the Legislative Reference Library, the second-highest number in the state’s history after Rick Perry’s vetos in 2001. Abbott took aim at the legislation of another voucher opponent, state representative Ernest Bailes, of Shepherd, a Republican who stopped a late-night attempt to pass a “school choice” bill without public comment. Abbott vetoed a bill from Bailes that would’ve established a utility district in Montgomery County, noting that, while the legislation was important, “it is not as important as education freedom.”

By that phrase, Abbott was referring to one of his policy priorities this year: passing a bill to create “education savings accounts,” the euphemistic name for a program that would offer taxpayer dollars to parents who enroll their kids in private schools. Amid nationwide right-wing outrage over alleged “woke” public school administrators teaching kids about sex and racism, Abbott has for months tried to pressure lawmakers on the issue. But while the Senate passed a bill that would have established a voucher program open to most students in the state, that measure never made it out of a key House committee after lawmakers there attempted to whittle it down. A second effort to pass vouchers, tucked in as an amendment to an education funding bill, also died in the House.

Clardy and other representatives observed that Abbott has typically shied away from fights with lawmakers. Now, however, facing pressure from wealthy pro-voucher campaign contributors and conservative evangelical activists, the governor has resorted to bullying.

During a teleconference meeting with Christian leaders last month, Abbott threatened to call lawmakers back to Austin at least twice this fall until they passed a bill—though he’s declined to give specifics on the type of legislation he’d like to see passed. If all else fails, Abbott, who did not reply to an interview request, implied he’d help elect a more compliant batch of Republican legislators in next year’s primary elections to get the job done.

“Abbott wins no matter what,” said Joshua Blank, the research director for the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin. “He basically told the Legislature, ‘I want you to return to me the gold-plated version of whatever policy I’m asking for. And to the extent that you fail to return that policy to me or give me a version of that policy that is not to the standards I want, I can blame you for that failure.’ ”

The optics of targeting members of his party still aren’t great—especially considering that voters aren’t as passionate about this issue as they are about others. “Vouchers,” “education savings accounts,” and “school choice” rarely rank among the top priorities for Texas’s Republican voters, according to polls. Only 34 percent of GOP voters ranked the issue as “extremely important” for the Legislature to address this session, while nearly double rated issues such as “school safety” and “parental rights” as priorities. Republicans in the Legislature are already in the headlines for being at one another’s throats. The fact that the party is arguing over this, Blank told me, isn’t a good look. “I mean, when the people you’ve chosen to lead are fighting amongst themselves . . . that certainly is not going to raise voters’ confidence in their ability to govern,” he said.

Clardy still can’t fathom why Abbott, who endorsed him in both 2017 and 2019, would try to defeat rural Republicans—traditional defenders of public schools in areas where few private schools are available—over a single vote. After all, Clardy said, he and other rural lawmakers represent the God-fearing, conservative rural voters who thrice helped elect the governor. Clardy noted that every school day in his district starts with the Pledge of Allegiance and Friday night football games commence with a prayer. On top of that, Clardy said, he’s not even wholly opposed to vouchers and is open to hearing ideas. The onus, he says, is on Abbott’s team to start proposing specific ideas about what it wants to see passed and to explain how its bill would affect specific rural districts. “Threatening and bullying is not effective leadership,” Clardy said. “I think you can go over and review the entire lexicon of Dale Carnegie and Zig Ziglar and not find bullying and threatening as a desired tactic. But here we are. And I don’t get it.”

A few “voucher lite” proposals, designed to be more appealing to rural Republicans such as Clardy, have begun circulating in the House, though Clardy said he hadn’t been approached yet by other lawmakers courting his vote. In August, the House Select Committee on Educational Opportunity and Enrichment released a report outlining recommendations for how to move forward on school finance, with a proposal for a voucher program that it said would not siphon funds from the public education budget. Other lawmakers have proposed limiting voucher eligibility to select groups of Texas students, such as those with disabilities or who attend an F-rated school. But during the regular session, Abbott said he would veto a voucher bill he deemed too limited in reach. “Parents and their children deserve no less,” he said.

Some voucher opponents remain defiant in the face of the governor’s pressure. Kyle Kacal, a state representative from Bryan–College Station, whom Abbott endorsed in 2019 and again in 2022 and who also voted against vouchers earlier this year, said this is a new tactic for the governor. “I get threats of primary challengers all the time,” he said, “but this is the first time that it’s rumored that the governor is going to get involved.” So far, at least, Abbott’s threat of finding a primary opponent for him wasn’t swaying him on the matter. “I’ve got House District Twelve to represent, and I will continue to represent that,” he told me. “The governor has got a big state to run. You know, we need to take care of our business and work together.”

Abbott isn’t the only one gunning for voucher opponents, however. Twenty-two of the 24 Republican state representatives who voted in favor of an amendment to the state’s budget that prohibited state funding from going to private and religious schools also voted in favor of impeaching Attorney General Ken Paxton. (Clardy and Four Price, of Amarillo, did not.) Both of these votes have brought these Republicans into not only Abbott’s crosshairs, but also those of right-wing billionaires and Paxton partisans, including Midland oilman and Christian nationalist Tim Dunn.

Earlier this year, Abbott toured the state with a vouchers pitch, stumping almost exclusively at expensive Christian private schools. He’s framed the matter as a way of empowering parents to protect their children from a “woke agenda” that he says is being pushed by some public school educators. But his repeated criticism of certain public schools ignores a big obstacle to convincing lawmakers to pass a voucher program—separate from the growing evidence that few such schemes improve educational outcomes. Public schools play a large civic role in many districts for parents and nonparents alike, particularly in rural areas. Many laugh at the notion, proffered by Abbott on the stump, that their public schools are sinister bastions for “wokeness.”

“That has to be the biggest joke I’ve ever heard,” said Randy Willis, the executive director of the Texas Association of Rural Schools, a collection of 362 public school districts that opposes vouchers. “Follow a rural principal around for a day. Do that and I guarantee you’ll see that we’re doing an incredible job—and with minimal resources. This whole idea of a ‘woke’ curriculum is ridiculous. They clearly don’t know rural Texas very well.”

In Clardy’s telling, “Abbott’s running out of tricks.” Other insiders think, however, that Abbott’s latest primary-challenge gambit—backed by the money of Dunn and other big campaign contributors—could be effective. “I think threatening conservative legislators in conservative districts sometimes is not an advisable course. But what he’s really saying is that he’s going to fight for this,” says Bill Miller, the cofounder of HillCo Partners, an Austin lobbying and public relations firm. Miller thinks “this play might work for the governor. It’s one way of showing how serious he is about it.” In a week, legislators will determine whether Abbott’s threat, however serious, is convincing.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Legislature

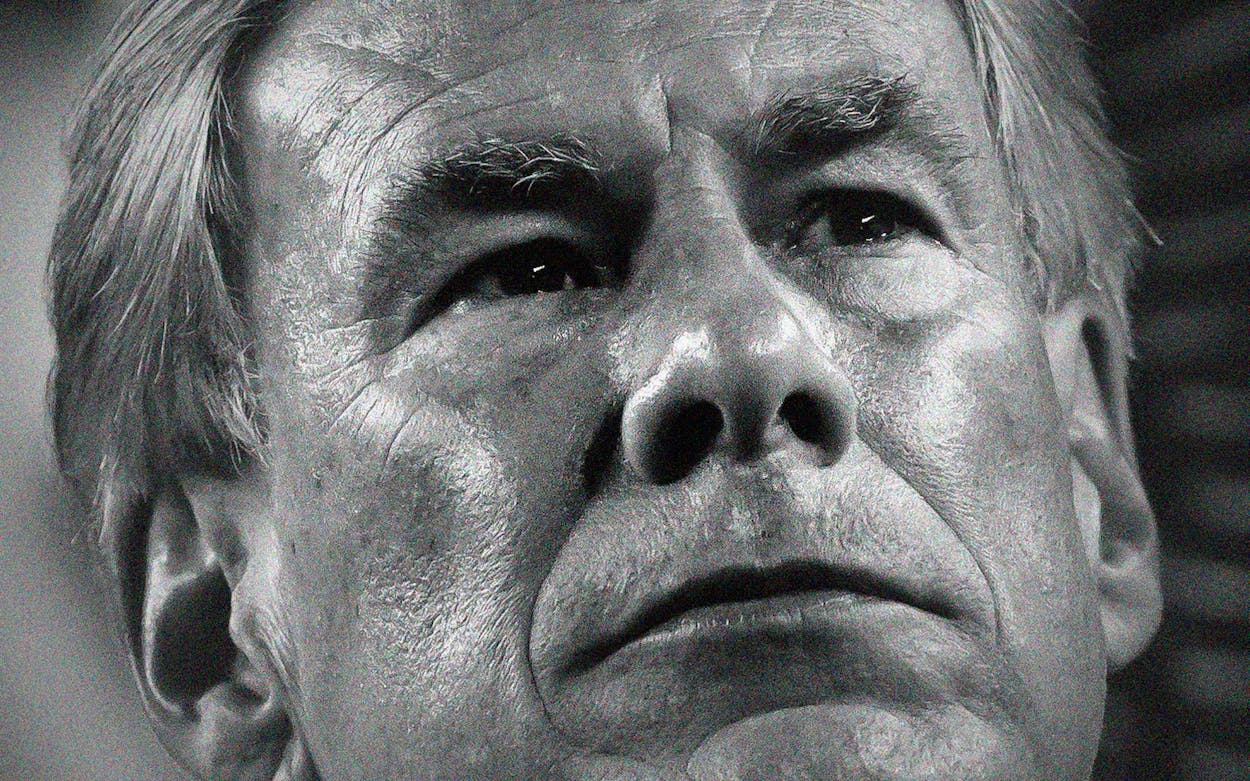

- Greg Abbott