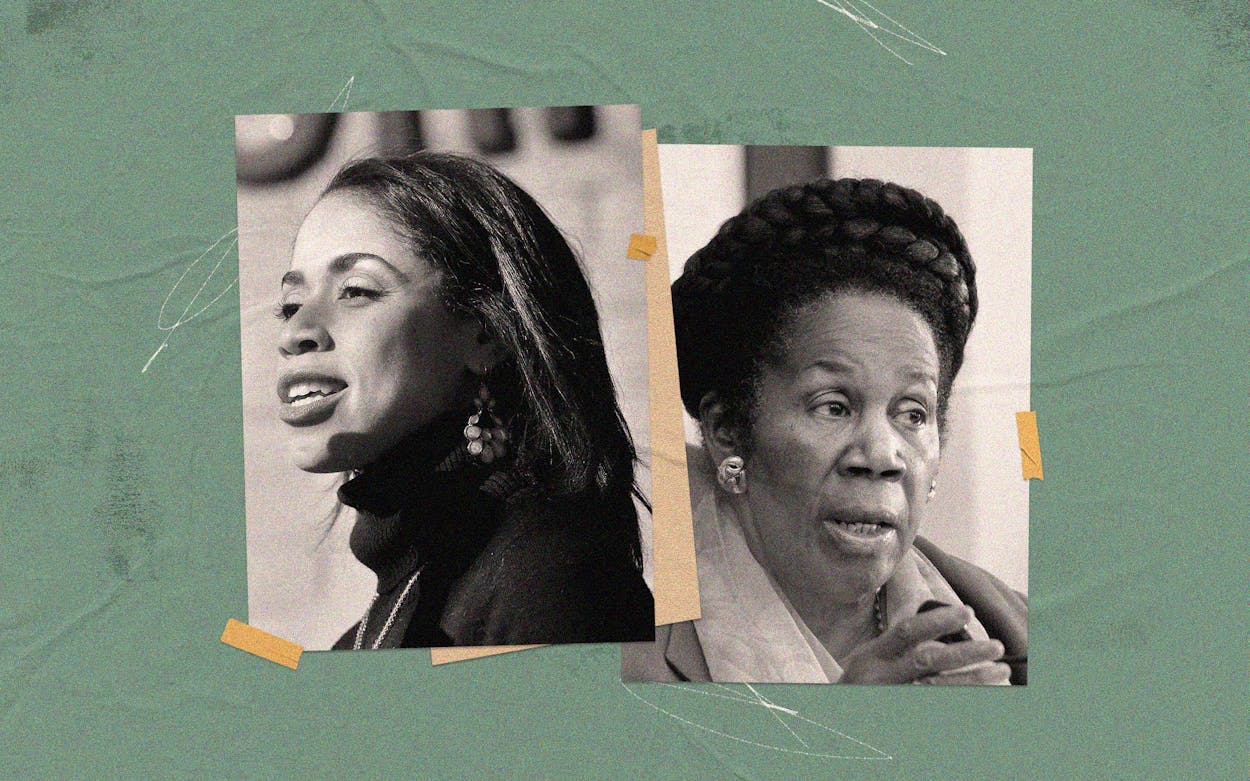

Amanda Edwards, who is seeking the Democratic nomination for Texas’s deep-blue Eighteenth Congressional District, rarely mentions incumbent Sheila Jackson Lee on the campaign trail. On a recent evening spent criss-crossing the sprawling district that encircles Houston like a lumpy donut, Edwards, a 42-year-old municipal-finance lawyer, delivered her stump speech at three neighborhood meetings. At the first two, held in majority-Black neighborhoods, she made no reference to her opponent beyond calling for “new leadership.” At the third, before a mostly white audience in Houston’s Rice Military neighborhood, she was a bit more direct.

“This race is not about me or Congresswoman Jackson Lee,” Edwards told the several dozen Houstonians who had gathered at Messiah Lutheran Church. “It’s about you getting the results that you deserve.” She predicted that, given the option of sticking with the incumbent at the voting booth, “those of you in this room will make a different choice.”

Since 2019, when she stepped down from the Houston City Council after a single term, Edwards has been a candidate in search of a winnable race. First, she launched a U.S. Senate campaign that ended with a fifth-place finish in the 2020 Democratic primary. Two years later she threw her hat into the ring for Houston mayor. But seven months before election day, Jackson Lee, a septuagenarian who has served in Congress for nearly three decades, shocked the Houston political world by announcing her own mayoral campaign. Seeing no path to victory, Edwards dropped out to run for Jackson Lee’s old seat. Had the longtime congresswoman become mayor, Edwards would have been the presumptive favorite to succeed her in Washington, D.C. Instead, Jackson Lee flamed out, losing to Democratic state senator John Whitmire by nearly thirty points in the December runoff.

Two days later, Jackson Lee announced she would run for reelection to her old seat. But her humiliating defeat in the mayoral election has made her look newly vulnerable. In the portion of the Eighteenth that falls within city limits, Jackson Lee only managed to win 22,478 votes to Whitmire’s 21,599. “It definitely pierced the veneer of her invincibility in the district,” said University of Houston political scientist Brandon Rottinghaus.

Once upon a time, Jackson Lee was the young upstart. In 1994, the then-44-year-old Houston City Council member unseated incumbent Craig Washington in the Democratic primary for the majority-Black district covering central Houston, winning a seat previously held by civil rights icons Barbara Jordan and Mickey Leland. Jackson Lee has served in Congress ever since, earning a reputation as—depending on whom you ask—either an indefatigable advocate for her constituents or a shameless self-promoter. No matter what you thought of her, there was no gainsaying her political strength. Election after election, decade after decade, Jackson has rarely faced anything more than token opposition in the low-turnout Democratic primary, which, given how few Republicans live in the district, amounts to winning the race.

That all changed last year thanks to Jackson Lee’s ill-fated bid for Houston mayor. Her late entrance into the race scrambled the crowded field of candidates hoping to succeed Mayor Sylvester Turner, who was stepping down after serving the maximum two terms in office. Shortly after her announcement, Edwards and former Harris County clerk Chris Hollins both left the race, Edwards to run for Jackson Lee’s congressional seat and Hollins to run for city controller. Hollins and Edwards are in the vanguard of Houston’s next generation of Black political leadership, but neither enjoyed the kind of support the Black community has long given Jackson Lee.

The incumbent now finds herself head-to-head with Edwards in the March 5 primary. For Edwards, running against the political stalwart without directly attacking her has been a delicate balancing act, especially since Edwards ended up endorsing Jackson Lee for mayor. “She was my choice for that race—it wasn’t an endorsement of her in a general sense,” Edwards recently explained. “When it comes to the Eighteenth Congressional District, I do think it’s time for new leadership and new ideas. Nothing about having endorsed her in the mayor’s race changes those facts.”

The race is further complicated by the long history shared by the two candidates. Between graduating with a B.A. from Emory University and entering Harvard Law School, Edwards, a Houston native who grew up in the Eighteenth Congressional District, interned in Jackson Lee’s Washington, D.C., office. Many of Jackson Lee’s former interns and employees have described a hellish workplace. Her office has one of the highest turnover rates on Capitol Hill, and an audio recording leaked during the mayoral campaign captures Jackson Lee berating a staff member with an expletive-laced rant. Edwards, however, declines to criticize her former boss. “I have gratitude for being given that opportunity,” she said about the internship. “I have not chosen to go down the path of focusing on what happens in her office.”

Edwards seems to pose an unprecedented threat, especially since the mayor’s race exposed Jackson Lee’s atrophied political muscle. “Sheila has never really had a formidable primary opponent, so she’s never had to go out and campaign, or raise money,” said Texas Southern University public affairs professor Michael O. Adams. “Having somebody in the race like Amanda, who can turn people out, who has represented the entire population of Houston as an at-large city council member, makes a lot of people think this will be a close election.” (Edwards had nearly $856,000 on hand as of her most recent Federal Election Commission filing, compared to Jackson Lee’s $223,000. Another former Jackson Lee intern, Isaiah Martin, also filed for the race but has since dropped out to work on her reelection campaign. Three other Democratic candidates have filed for the race but had not reported raising any money as of the filing deadline.)

On a recent Monday afternoon, Jackson Lee called me from a commercial flight that was about to take off from Houston, heading to Washington, D.C. Speaking over the in-flight announcements, the congresswoman gave her reelection pitch. She listed her major accomplishments in Congress, including the part she played in creating the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund, establishing Juneteenth as a national holiday, and securing disaster relief for Houston in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. She cited her leadership role as deputy whip of the Democratic Caucus, and her senior positions on the Budget, Homeland Security, and Judiciary committees. “You have to understand how Congress works,” she said. “Congress is a creature of bipartisanship, a creature of collaboration, and a creature of seniority. You have to have all of those elements to get your legislation passed.” (Though bipartisan negotiation is increasingly less a hallmark of the legislative process).

Edwards countered that “the congresswoman has seniority, but the question is what you do with that seniority.” Pressed to specify how she would legislate differently than Jackson Lee, Edwards reverted to campaign boilerplate about “new solutions,” “a proactive vision,” and “a different set of tools.” When I asked why she dropped out of the mayor’s race to run for Congress, she replied that “our mission could still be carried out in a way that would enable us to fulfill the mission that we set out to fulfill.” Her campaign rhetoric is filled with such circular locutions, which seem intended to leave a good impression while saying as little as possible. When I asked for concrete policy differences between her and Jackson Lee, Edwards gestured vaguely to the need for more public housing—something that the incumbent also supports.

In the end, none of this may matter. Edwards is personable and well-funded, while Jackson Lee is a polarizing figure, especially among white and Hispanic voters. The Eighteenth Congressional District has changed considerably since Jackson Lee was first elected in 1994. After multiple rounds of gerrymandering by Republican state legislators, the district is now 46 percent Hispanic, 31 percent Black, 23 percent white, and 5 percent Asian. (In the 1990 Census, the district was 51 percent Black, 31 percent white, 15 percent Hispanic, and 3 percent Asian.) Whitmire performed well in the Hispanic community during his mayoral race, thanks in part to the endorsement of political leaders such as U.S. representative Sylvia Garcia. (Garcia has not endorsed a candidate in the congressional race, although Edwards is supported by city council member and mayoral candidate Robert Gallegos.) In a low-turnout election, if Edwards can win similar Hispanic support she may have a chance. Adams, the Texas Southern professor, told me that Jackson Lee is hoping for strong turnout from her base of older Black women.

Jackson Lee is also counting on big-name endorsements. Her mayoral campaign received support from the likes of former president Bill Clinton, former Houston mayor Sylvester Turner, Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, and Harris County Commissioner Rodney Ellis. Ellis, a longtime Houston power broker who is also supporting Jackson Lee’s reelection to Congress, was one of the politicians who encouraged Jackson Lee to run for mayor, believing that progressive Democrats needed a big name to defeat Whitmire, a centrist with close ties to state Republican leaders. “I thought that she had the best name ID and the ability to go out and raise money,” Ellis told me. “I think she would have been wise to get into the race earlier. My sense is that the timing was just bad.”

On a cold Saturday morning last month, I drove to Houston’s Sixth Ward neighborhood to meet with about a dozen volunteers who had gathered to block-walk for Edwards. While waiting for the candidate, who was running late, I spoke to several of the volunteers, who expressed concern that Jackson Lee appeared to be obstructing the next generation of Black political leaders—first by forcing Hollins and Edwards out of the mayoral race, then by refusing to retire from Congress.

“A lot of folks are disappointed that she jumped into the mayor’s race,” said Nakia Hillsman, a longtime public employee. “And then she jumped back in the congressional race. That’s motivating people to get out [for Edwards].” Tajj White, a University of Houston undergraduate studying political science, nodded along. “As a leader,” he added, “you should be willing to pass that torch down.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston