Houston is one of the country’s youngest major metropolitan areas, with a median age of 34—five years below the nationwide number—and nearly a quarter of its population is younger than 18. It’s a dynamic, diverse, fascinating, and often-infuriating place whose defining trait has always been optimism. The outgoing mayor, Sylvester Turner, was raised in the impoverished neighborhood of Acres Homes by a mother who worked as a maid at downtown’s Rice Hotel. He frequently quotes her mantra that “tomorrow will be better than today.”

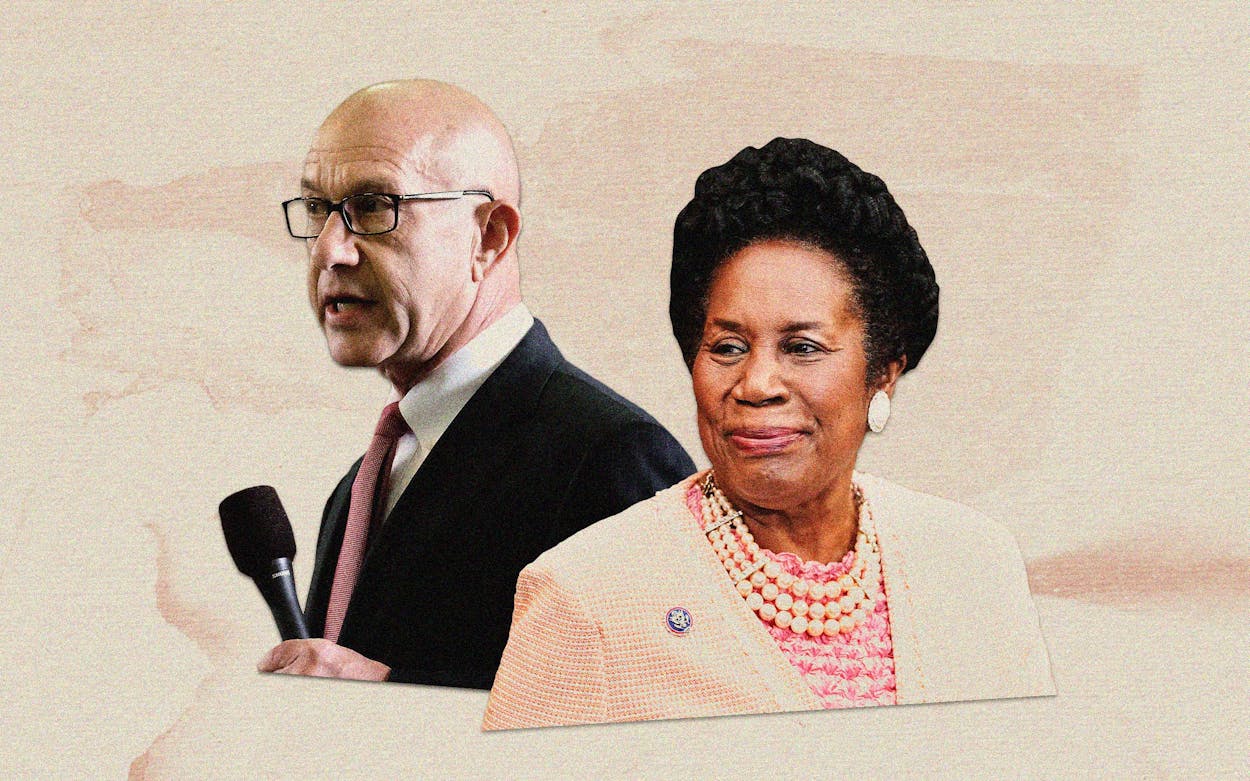

Yet the leading candidates in November’s election to succeed the term-limited Turner seem like figures from the past. State senator John Whitmire has served in Texas government since 1973, while U.S. congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee has represented her Houston district in Washington, D.C., since 1995. Jackson Lee is 73 and Whitmire is 74. Turner is 68, and he became mayor after spending 27 years in the Texas Legislature. Houston City Hall is starting to look like the political equivalent of Major League Soccer, the last stop before retirement for superannuated stars such as David Beckham and Lionel Messi. Speaking of Jackson Lee and Whitmire, Rice University political scientist Bob Stein observed, “These are two people who have been in politics longer than most people have been alive.”

It didn’t have to be this way. After Whitmire declared his candidacy in 2021, the next to announce was 37-year-old Chris Hollins, a liberal Democrat who innovatively administered the 2020 presidential election in Harris County. He was soon joined by former Houston City Council member Amanda Edwards, a 41-year-old Democratic rising star. Both Hollins and Edwards hoped to win Houston’s key Black vote, which usually makes up around 30 percent of the voting population. But neither could compete with Jackson Lee’s strong support in that community, and after she entered the race in March, both dropped out—Hollins to run for city controller and Edwards to seek Jackson Lee’s congressional seat.

“It’s not necessarily the scenario I would have envisioned when I started my bid for mayor,” said Edwards, who worked in Jackson Lee’s congressional office after college and has endorsed her mayoral bid. “But that’s what you have to be prepared for when you’re in the public service arena.” (Hollins declined an interview request.) Edwards and Hollins “were in a position to be future city leaders,” said University of Houston political scientist Brandon Rottinghaus. “Whitmire’s early decision to enter the race and Jackson Lee’s late decision basically cemented the old guard’s role in city politics.”

In a recent University of Houston poll, 34 percent of likely voters said they planned to vote for Whitmire in the general election, while 32 percent planned to vote for Jackson Lee; none of the twelve other candidates received more than 3 percent support. The poll shows the race likely heading to a runoff between Whitmire and Jackson Lee, neither of whom were available for an interview before Texas Monthly’s deadline.

Houston mayoral elections are officially nonpartisan; candidates don’t run as Democrats or Republicans. In this increasingly blue city, though, Republicans typically coalesce around a single candidate. In 2015 they backed businessman and political independent Bill King, who lost to Turner in the runoff by about 4,000 votes. In 2019 they turned to flamboyant trial lawyer Tony Buzbee, who lost by more than 24,000 votes.

This time around, the local Republican establishment is backing Whitmire, a moderate Democrat who maintains good relations with Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and other state Republicans. Whitmire has received endorsements from GOP megadonors, including Houston Rockets owner Tilman Fertitta, right-wing furniture-store legend Jim “Mattress Mack” McIngvale, beer distributor John Nau, and real estate developer and tort-reform advocate Richard Weekley. Many of Whitmire’s supporters backed Republican Alexandra del Moral Mealer, a political newcomer who came within two percentage points of unseating Democratic Harris County judge Lina Hidalgo last year. “John Whitmire is the candidate of the Republican leadership in Austin,” said Stein, the Rice University political scientist.

The appeal of Whitmire over Jackson Lee to Republicans has less to do with policy—both have relatively moderate voting records—than with style: Whitmire is the consummate insider, a good ol’ boy cutting deals behind the scenes, while Jackson Lee is a rhetorical bomb thrower who once likened the tea party to the Ku Klux Klan. Unlike Whitmire, who is known for working across the aisle, Jackson Lee has few allies on Capitol Hill and is a polarizing figure in Houston. “She is just one of those politicians that people either love or hate,” said University of Houston political scientist Renée Cross, who helped conduct the recent poll. “We see something very similar with Donald Trump. Their supporters are extremely loyal, but their detractors are very vehement.”

The University of Houston poll essentially presents a story of two races. In a fourteen-candidate field, Whitmire and Jackson Lee appear to enjoy almost equal support. But in a runoff, Whitmire’s support jumps to 51 percent, while Jackson Lee picks up only 1 percentage point, inching up to 33 percent, with 13 percent of voters undecided. The reason appears to be widespread negative perceptions of Jackson Lee. Nearly half of poll respondents held an unfavorable opinion of the congresswoman, and 44 percent said they would not vote for her under any circumstances. “She’s got her base of voters, but she can’t really expand it because of how well-known she is,” one Democratic political insider, who requested anonymity to speak candidly, told me. “She’ll make the runoff, but I don’t think she beats any major candidate in the runoff.”

A simplistic way to conceptualize Houston elections is to imagine three voters: a white Democrat, a Black Democrat, and a Republican. You need two out of the three to win. (Hispanic Houstonians account for roughly 45 percent of the city’s population but make up only about 20 percent of voters. Asian Americans, whose numbers are rising rapidly in Houston and across Texas, still comprise only 7 percent of Houston’s population.) According to the University of Houston poll, Jackson Lee leads Whitmire among Black likely voters by 65 percent to 14 percent, while Whitmire leads among white likely voters 42 to 21 percent. Whitmire currently enjoys the support of 56 percent of Republicans, compared to 2 percent for Jackson Lee. In a potential runoff, Jackson Lee maintains her support among Black likely voters while Whitmire’s share of white likely voters increases to 63 percent.

Whitmire enjoys several structural advantages. He came into the campaign with a massive war chest, which has been swelled by his subsequent fund-raising. He’s won many major endorsements, including those of the Houston Organization of Public Employees, the Houston Police Officers’ Union, and the Texas Gulf Coast Area Labor Federation. And during a period of elevated violent crime, his decades of experience as chair of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee may reassure worried residents. Although violent crime has fallen over the past year, it remains well above pre–COVID-19 pandemic levels. The University of Houston poll found that crime was the number one issue among likely voters—83 percent said it should be a top priority of the next mayor—followed by flooding and road conditions. “Whitmire has completely mowed the grass tops,” the Democratic insider told me. “He’s got every elected, every business leader.”

The major knock on Whitmire is that he lacks any sweeping vision for the city. Unlike Turner, who campaigned on pension reform (which he achieved) and reducing income inequality (still very much a work in progress), Whitmire is running on his ability to deliver marginal improvements to the city’s quality of life. He has promised to implement a reentry program for released prisoners, use voluntary inmate labor to pick up trash and debris, combat homelessness, and improve garbage pickup.

Whether it chooses Whitmire or Jackson Lee, Houston will be electing an elderly leader at the end of his or her political career. Will the next mayor be able to meet the challenges facing the nation’s fourth-largest city—not just crime but also traffic congestion and the impacts of climate change—or will they treat the job as political sinecure? Like the United States, which faces the prospect of a presidential election between an 80-year-old Joe Biden and a 78-year-old Donald Trump, the city seems to be sliding into gerontocracy. “There’s been so much change in Texas politics,” said Rottinghaus, the University of Houston political scientist. “But not in Houston. In Houston, the old guard still rules.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston