Tayhlor Coleman is behind the wheel of “Barb” heading west on U.S. 290, in the pretty farm and ranch country between Houston and Brenham. “Barb” is the name she’s given her home on wheels, a white 2021 Sprinter Ram ProMaster van that’s as Texas as they come. On the dash: Coleman’s cowboy hat. In the passenger-side door: a copy of Lonesome Dove. On the stereo: Kacey Musgraves. “I love Texas so much,” she says. “Being from Texas is a personality for folks. That bug is definitely strong for me.”

Just a few months into the pandemic, Coleman had moved from her lonely apartment in Washington, D.C., back home to her parents’ house in Houston’s Third Ward. Like a lot of folks, the 33-year-old political strategist found herself falling down an “Instagram rabbit hole” during the pandemic, obsessively looking at #vanlife posts and dreaming of escape from #pandemiclife. An itinerant lifestyle appealed to Coleman; she had spent years as a Democratic campaign worker, so she was used to living on the road.

“Barb”—named after pioneering congresswoman and civil rights leader Barbara Jordan—is a custom job. Tahylor did some of the work herself, including the wiring and the flooring. “I had no clue what I was doing,” she says. With the help of YouTube, she figured things out. Then, she found a van-build shop in Austin that was willing to do the rest as part of Van Go, a Magnolia Channel show on customizing vans. The pros installed an outdoor shower, a reclaimed-wood counter, and bluebonnet-covered accent panels on the inside of the rear doors.

As bespoke as Barb is, she’s still a tiny home on wheels. Coleman is six feet tall; her braids almost brush the ceiling when she’s standing up. Keeping clutter in check is a constant challenge. As the van makes a quick lane change on busy U.S. 290, light rain splattering the windshield, the stuff of her daily life clangs around in the back. “Instagram is such bullshit,” Coleman says. “You can see the reality: the van doesn’t look spotless, curated twenty-four-seven.”

Nonetheless, Coleman has embraced #vanlife. Since she got the van back from the Van Go guys in October, it’s taken her to parts of Texas she’s never seen—Palo Duro Canyon, for example—and she’s enthusiastic about documenting her travels on Instagram. (Her bio: “Into #vibes, #vanlife, & #voting rights. Cowgirl up.”) “It’s pretty sweet, I’m not gonna lie,” she says. As her travel plans coalesced, however, Coleman began adding a more serious mission to her goals of saving on rent and posting FOMO-inducing pics. She plans to spend most, if not all, of 2022 traveling the state from stem to stern to register voters in as many counties as possible. Coleman is also using social media to document what she sees as a new crackdown on voting rights—all while working a day job as a senior account executive for a Democratic media firm, AL Media Strategy.

Her Instagram savvy has yielded a mixture of glam content (Coleman posing at a Hill Country swimming hole; a Big Bend vista from the perspective of Barb’s couch) and more didactic material (a three-minute IG reel of Coleman explaining the nuts and bolts of how to fill out voter-registration forms as a volunteer registrar). Her media savvy has landed her several spots on MSNBC and in the Houston Chronicle. Along the way, she is engaged in a project of self-education. A seventh-generation Black Texan, Coleman is digging into her family’s history as actors in the long struggle for voting rights, and she’s learning firsthand how onerous and arbitrary many Texas voter registration laws are.

In mid-February, I catch up with Coleman in Cypress, an exurb on the northwest edge of Houston’s sprawl. She’s coming from her parents’ home in the Third Ward, the rapidly gentrifying historically Black neighborhood in Houston’s downtown where she grew up. We ride together to Washington County, a bucolic patch of Texas with rich soils and gently rolling hills. Coleman’s family has deep roots in the area. According to family genealogy, her dad’s ancestors were brought as slaves to Washington County in the 1840s to work the region’s bustling cotton plantations. Her relatives still own land in the county, and Coleman fondly remembers summer trail rides at a family ranch near Chappell Hill. Her parents taught her at an early age about Jim Crow, and her grandmother told her about an uncle who had been lynched. But it wasn’t until a lull in campaign work about six years ago that she began researching her family’s history in the area.

She discovered that her ancestors had been involved in a profound chapter in American history. During Reconstruction, Washington County’s formerly enslaved people enjoyed a flourishing of freedom. They started schools, built a cotton gin, and worshipped in newly formed churches. They also began exercising political power. In her van, Coleman keeps a framed copy of a voting roll from 1867, the first year Black men in Texas could register to vote. Two of her ancestors’ names—Cujo Kinlaw and Cato Felder—are on the list. “It’s hard to describe the rooted feeling from knowing such deep history,” she says. “It’s grounding, especially in a time when it feels like you don’t know the country you grew up in anymore.”

In the 1870s and 1880s, African Americans from Washington County took advantage of their hard-earned political power. They were elected to local offices and to the Texas Legislature, served on juries, and were deeply involved in building the Republican party, which thrived for a time on an alliance between Black voters and their white allies, mostly Germans who supported the Union in the Civil War. But, as Coleman learned from reading scholarly articles and the archives of the Brenham Banner, Black political power provoked a violent white backlash. In the 1886 election, gun-toting masked men stole ballot boxes in three of Washington County’s heavily Republican precincts. At one of the polling sites, a Black poll worker fought back, shooting and killing one of the intruders, who happened to be the son of a white Democratic candidate for county commissioner. In retaliation, a white mob broke into the jail at Brenham, kidnapped three Black men who had been arrested, and lynched them about a mile outside town. The U.S. Senate held hearings on the Texas “election outrage,” as the violence in Washington County came to be known, and devised legislation, the Federal Elections Bill of 1890, to protect the rights of Black voters in the South. It was defeated by a filibuster in the Senate—and Jim Crow settled into his 75-year reign.

Coleman can’t help but see a through line between then and now. “I don’t at all try to compare the things that even my own grandmother lived through to some of the things that we’re seeing today,” she says. “But I do think nothing under the sun is new. And the very same motivation that motivated a lot of the violence and the attempt to hold on to power by any means necessary in 1886, I absolutely believe we are seeing a lot of that today. The parallels are, for me, frankly alarming.”

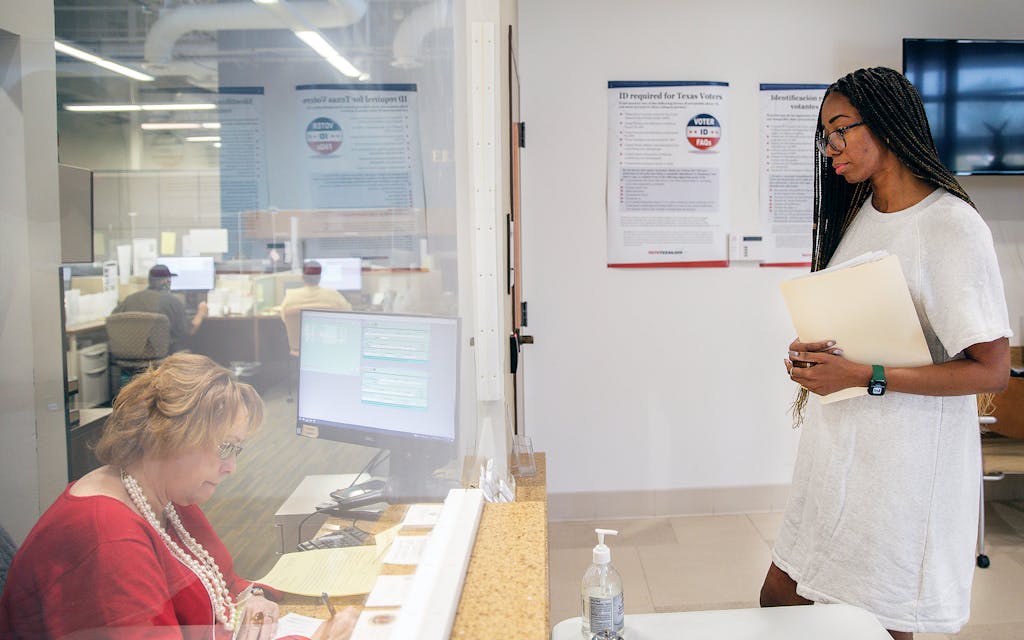

Coleman pulls Barb up to the curb outside the Washington County courthouse in Brenham. Her goal is to get certified to register voters—this will be her fifth county—but first she has to find the elections administrator, Carol Jackson. We’re turned away at Jackson’s office in the courthouse; she’s across the street, overseeing early voting for the March primary. “This is van life,” Coleman chuckles. “Figure it out as you go.” At the polling place, Jackson is friendly but not exactly thrilled to see us. “This is not a good time because we have an election going on,” Jackson says.

As the Legislature has piled up new rules and restrictions around voting over the past decade—from requiring photo ID to vote to limiting the hours that polls can be open—it’s fallen to local elections officials to manage all the mandates. And they often seem overwhelmed, Coleman says. Elections administrators have also been besieged by angry partisans, conspiracy-minded activists, and crusading state-level politicians. The sweeping elections bill passed by the Legislature last year threatens administrators with a felony, and two years in jail, if they send mail-in ballot applications to voters who haven’t asked for one, among other new or enhanced criminal offenses. Coleman feels bad about bothering Jackson, but she doesn’t know when she’ll be able to stop by in Brenham again. After a short wait, Jackson takes us back to her office at the courthouse, where the tension eases. Coleman fills out a state-required form and then leaves as a legal deputy registrar in Washington County—one of just three Jackson had minted so far in 2022.

At first, last fall, Coleman thought she would visit all 254 counties in Texas, but she quickly ran into logistical problems. First, the state is huge, and as any politician who has embarked on a 254-county tour will tell you, it doesn’t necessarily make sense to spend a day chasing votes, or unregistered voters, in Loving County (population 64). Also, Texas makes it hard to register to vote; ours is one of only eight states not to offer online registration. As a result, signing up voters is largely a paperwork exercise that falls to volunteers called deputy voter registrars. The analog nature of this process was underscored in January, when the Texas secretary of state’s office announced that it was running low on voter-registration forms because of supply-chain issues.

Complicating things further, there is no way to become a statewide deputy voter registrar. State law stipulates that a volunteer—only Texas residents are eligible—must be certified in each county where he or she wants to register voters. And most counties do not allow online certification. That means Coleman generally must show up in person, during business hours on a weekday, and find an often-busy clerk to give her the necessary paperwork. Deputy registrars also aren’t allowed to register voters who reside in a different county—a lesson Coleman learned in February, when she helped two students in Tyler fill out forms, only to realize later that they lived in adjacent counties. The forms were junk. She had to call the students to tell them about the snafu. Completed registration forms have to be returned to the elections administrator within five days—failing to do so is a criminal offense, a penalty that a Bexar County administrator recently warned Coleman about. If you’re confused or bored by this recitation of rules and regulations: well, that might be the point. Texas probably has the most burdensome voter registration laws in the country—a massive impediment to statewide registration drives.

Almost none of this is new. The voter deputy registrar system was created in 1986, and made stricter by the Legislature in 2011. But critical attention has shifted to other aspects of the voting system in Texas, most recently the sweeping legislation passed in 2021 to restrict voting, including a requirement that voters must provide ID in order to receive a mail-in ballot—a provision that contributed to the rejection of at least 23,000 ballots during the March primary, a 13 percent toss-out rate, up from 1 percent in 2020.

“Every barrier, every obstacle, every new procedure, every new requirement adds a cost to voters,” said James Slattery, a senior staff attorney at the Texas Civil Rights Project, a nonprofit that opposed the 2021 legislation. “For the most part, a change will be made and you could say, ‘Well, come on. Is this the one change that’s going to make this not a free and fair election?’ Probably not. But when you add all of them together, it’s like voters have to run an obstacle course to get from wanting to vote to being able to cast a ballot.”

After we wrap up in Brenham, Barb gets back on U.S. 290. Destination: Austin. Later today, Coleman is meeting up with Black Voters Matter, a national voter-registration nonprofit that tours the country in a bus plastered with the mug shots of Freedom Riders, but first she wants to get certified in Travis County. At the bustling county building, she quickly hits a snag. The elections office is doing certifications online only, because of the coronavirus pandemic, but Coleman first needs to talk to the official in charge. And she’s at lunch. So that’s what we do—go to lunch, and wait for the official to call. “I’m shocked,” Coleman says. “This is why we shouldn’t have to do all this in order to just register voters. It’s insane.”

After lunch, Coleman gets a call: she can fill out the paperwork online and meanwhile is free to register voters in Austin. Coleman finishes her day registering voters at Huston-Tillotson University, an HBCU in East Austin, and then drives to Dallas that night to catch up with the Black Voters Matter bus. A few days later, the crew is in East Texas to register voters. She’s glad she took the time to get certified in Smith County; on a couple of stops, she is the only voter deputy registrar. She personally signs up about fifteen voters.

In Tyler, during the fifth day of early voting ahead of the March 1 primary, Coleman is waiting in line to get certified in Smith County when she overhears—and records—a conversation between an elderly Black man and a county official. The man wants to turn in an application for a mail-in ballot on behalf of his mother—it’s the last day to do so for the primary—but the official politely informs him that his mom has to be present in order to show ID. “Well, she’s ninety years old,” the man says, before leaving. Coleman later posts the video on Instagram and then, wearing purple sunglasses and sitting in Barb, addresses her followers. “Yes, there are really people being disenfranchised over this bill.” While that’s certainly true in general, it’s not quite right in this instance. The clerk is correct, mostly—long-standing state law stipulates that a voter must turn in her own mail-in ballot application, though there’s nothing that says she must present an ID. If a voting rights activist and an elections clerk can’t keep things straight, it’s no wonder that many voters can’t either.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Houston

- Cypress

- Brenham