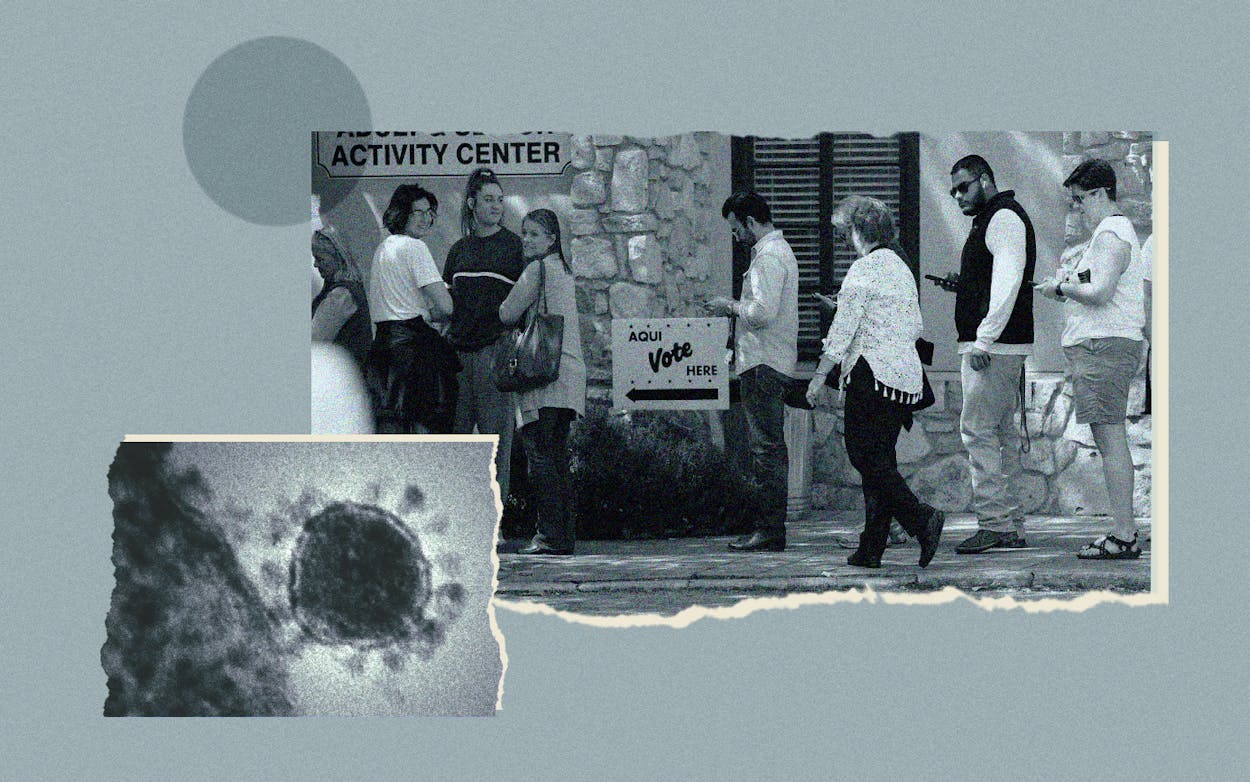

In the wake of Super Tuesday, Texas made national headlines for its Election Day dysfunction. In Harris County, six-hour lines snaked outside of polling centers, keeping some Texans from casting their ballots until long after polls were supposed to close. In the weeks since, local election administrators have been tasked with fixing problems exacerbated by the steady closure of polling centers—750 polling places closed statewide between 2012 and 2018, more than in any other state—and by an aging crop of poll workers. Now, local election officials must grapple with a compounding, more daunting challenge: the potential impact of a pandemic on upcoming elections that are predicted to draw unprecedented crowds of voters. And they have received little to no guidance from the state on what to do.

On Wednesday, Governor Greg Abbott issued a proclamation allowing local elections administrators to postpone elections scheduled for May 2 until November, which at least two counties—Galveston and Williamson—have done. “Right now, the state’s focus is responding to COVID-19—including social distancing and avoiding large gatherings,” Abbott said in a statement. “By delaying this election, our local election officials can assist in that effort.”

But the early May elections Abbott are proposing be delayed deal with hyper-local issues like bonds or municipal utilities, and typically have much lower voter turnout than primary runoffs, set this year for May 26, or general elections. In high-turnout races, voters will be at a much higher risk of contracting or spreading COVID-19 while standing in line waiting to vote, or tapping a touch screen to select candidates. In the weeks since the first confirmed case of the coronavirus emerged in Texas—reported by public health officials in Fort Bend County the day after Super Tuesday—the state has offered no proposals on how to mitigate the outbreak’s impact at the polls.

“We’ve been in contact with [the state],” said Michael Winn, director of elections in Harris County, the most populous county in Texas. “They haven’t responded back.”

Secretary of State director of communications Stephen Chang did not respond to Texas Monthly’s requests for comment.

Abbott and Secretary of State Ruth R. Hughs faced pressure this week from legislators and advocacy groups to take more immediate action addressing those higher-turnout elections—in particular, to expand the state’s vote-by-mail program so that it applies to all Texans.

Texas’s vote-by-mail exceptions currently cover all voters 65 years or older, disabled voters, and voters who are going to be out of the county during voting periods. State law also says voters are eligible for early voting by mail “if the voter has a sickness or physical condition that prevents the voter from appearing at the polling place on election day without a likelihood of needing personal assistance or of injuring the voter’s health.” In the 2018 midterm elections, the state received 370,000 votes by mail, out of 12.25 million total voters.

In a letter sent Tuesday to Abbott and Hughs, 26 advocacy groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas, the Texas Civil Rights Project, and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, called for the state to tell local elections officials that the final exception applies to every eligible voter amid the coronavirus outbreak.

“Under these unprecedented circumstances, it is clear that merely going to a crowded venue, such as any polling location, in person constitutes a likelihood of injuring a voter’s health,” the letter said. “And the more people who risk their own health by gathering in groups also exponentially increases the risk of spreading the disease to others and causing greater societal damage. Texans should not be asked to choose between their physical well-being and their fundamental right to vote.”

Two state legislators—Representative Celia Israel of Austin and Representative Terry Canales of Edinburg—and Democratic Party chair Gilberto Hinojosa also sent letters to Abbott, urging him to take similar measures.

Israel formally requested that Abbott schedule a conference call with members of the Texas Senate State Affairs Committee and the House Elections Committee, to discuss potentially postponing the primary runoff elections, as other states have done, or holding them by mail only. She noted that polling locations have the potential to become “a major transmission point” of COVID-19. “This call should take place no later than Friday, March 20th, given the decision-making timeline surrounding these elections,” Israel wrote. A spokesman for Israel said Thursday night that Abbott did not respond to the letter.

Canales noted in his letter that 22 states currently have vote-by-mail programs that apply to all registered voters (three states—Colorado, Oregon, and Washington—have all-mail elections) and called for Texas to adopt such measures.

And in a letter sent Monday to Secretary of State Hughs, Texas Democratic Party chair Gilberto Hinojosa recommended the May 26 primary runoffs be held entirely by mail.

If the state did expand its vote-by-mail program, local elections officials would then need to figure out how to accommodate what would be an unprecedented increase in mailed ballots. For example, in Harris County, where there are 2.6 million registered voters, the most by-mail ballots ever sent out was 115,000, in the 2016 general election, according to Winn. The county would need to quickly ramp up to meet demand if the state decides to expand the program.

“Even with 200,000 or 300,000 qualified to vote in a by-mail program, that would be just an extraordinarily exorbitant amount of ballots that we would have to try to get out,” Winn said. “And so we’d probably have to look at incredible resources and probably outsourcing.”

According to Anthony Gutierrez, executive director of the voting watchdog group Common Cause Texas, mail-in voting is just one issue local election administrators must take into account when preparing for elections during a pandemic. Ensuring voting machines are safe to touch, that cleaning supplies won’t damage machines or ballots, finding alternatives if elderly poll workers can’t come to work—“you can’t do that overnight,” Gutierrez said. “The problem with all of these emergency election measures is that none of them are turn-key. All of them are going to take some amount of time to implement. It’s all doable, but it requires that people are doing things now to plan for that.”

Some counties quickly decided to postpone the May 2 elections after Abbott’s proclamation, giving them more time to focus on getting ready for the bigger elections later on.

“We feel that it’s safer for the public and for our staff,” Galveston county clerk Dwight Sullivan said. “We’ve got many high-risk people involved in elections, and with early voting starting just weeks away, we thought it was the right decision.” Sullivan added that the decision to postpone came in part because some local polling locations, like schools or communities that house elderly people, are places that have prohibited or significantly restricted public entry because of concerns of spreading COVID-19.

In the absence of clear guidance from the state on what to do for the May 26 primary runoffs or the November general election—which they do not currently have the authority to postpone—local elections officials are preparing for a multitude of ways the coronavirus outbreak might impact Election Day.

That includes scrambling to stock up on hand sanitizer, surgical masks, gloves, and disinfectant wipes to clean touch-screen voting equipment. “We do have some limited stock [of sanitation supplies], and we have put in orders for those, just like probably all the other nine thousand jurisdictions across the country,” Winn said. “I think it’s probably going to be a strain on trying to get those things in.”

Further complicating matters is the fact that poll workers are typically older adults, and are at a higher risk of dying if they contract COVID-19. Sullivan said that his office is training more workers than would be needed to staff polling centers, anticipating any potential personnel shortages should some poll workers be quarantined or too ill to work on Election Day.

“I think all local election officials are trying to get more guidance,” Winn said. “I really think that the state is trying to figure out what their options are, and at this time I think it’s too early for them to make a decision on what’s going on, because they don’t know quite what the magnitude of the problem is—the country doesn’t even know what the magnitude of the problem is. Everybody’s basically waiting to see what’s going to happen.”

Before the coronavirus crisis emerged as a pressing concern, Gutierrez of Common Cause Texas had spent much of his time since the March 3 primary election working on measures aimed at preventing excessively long lines at polling places. Gutierrez attributed the problems on Super Tuesday to “the lack of the state caring enough about voting to really invest in the election infrastructure.”

Now, amid a pandemic, Gutierrez says it is far more critical for the state to devote appropriate resources to the election process.

“It’s not just to prevent long lines in November, but also to make polling sites safe, to make sure that everyone has a chance to vote and they don’t stay home, either because of a long line or because of a public health crisis,” Gutierrez said. “The state’s going to have to step up and find some resources somewhere. They always seem able to do that when it’s something politically advantageous to the people in power. But they’ve got to figure out a way to do it now.”

As we cover the novel coronavirus in Texas, we’d like to hear from you. Share with us your tips or stories about how the outbreak is affecting you. Email us at [email-hidden].

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott