He is the youngest of the major statewide officeholders, but he happens to have the most famous last name in Texas politics. At 39, George P. Bush is serving his first term as the commissioner of the General Land Office, which, among other things, manages the state’s 13 million acres of public land and uses its revenue to invest in the Permanent School Fund. Despite the fact that his father, Jeb, a candidate for the Republican nomination for president, was the governor of Florida, George P.’s Texas roots are solid: he was born in Houston, attended Rice University and the University of Texas at Austin School of Law, and lived in Fort Worth. It doesn’t hurt that his grandfather George H. W. Bush arrived in the state as a young man to make his fortune before becoming president, or that his uncle George W. Bush was twice elected governor of Texas before moving into the White House himself. (One thing you notice about George P. is that he is quick to laugh—and that laugh sounds an awful lot like his uncle’s.) Today, he lives in Austin with his wife, Amanda, and their two small children.

Bush’s own path to public office involves both military and private-sector experience, which seems right on script for his family. He was an officer in the United States Naval Reserve and served in Operation Enduring Freedom in an intelligence capacity, and he co-founded a real estate private-equity firm and an oil-and-gas investment firm. He used that experience to help make his case to the voters when he ran for office in 2014, and during the past year, he made headlines by ending the long-standing relationship with the Daughters of the Republic of Texas to run the Alamo and initiating a “reboot” of the GLO that included the departure of some veteran staff members and the trimming of the agency’s operating budget.

Of course, any conversation about Bush’s career ultimately leads to a discussion about his future. He has entered office at a moment when the energy in the Republican party seems very much directed away from any legacy politician, particularly one whose views may not be conservative enough for the base. In fact, many have noted the irony of Bush’s endorsing Ted Cruz for the U.S. Senate in 2012, calling him “the future of the Republican party.” That may have been a smart play at the time, in his effort to connect with the tea party in Texas, but today it is Cruz who is far ahead of his father, in Iowa and elsewhere. What kind of role do the Bushes have in this new era of politics? The answer to that will start to become clear later this year.

Brian D. Sweany: We are talking at an interesting time: it has been almost one year to the day that you were sworn in as the commissioner of the General Land Office, and we are less than four weeks away from the Iowa caucuses, where your father is on the ballot. I want to discuss both, but let’s start with your job: How would you describe your performance over the past twelve months?

George P Bush: I campaigned for this job for two years in four core areas: veterans affairs, the Alamo, generating more revenue by leveraging my background as an oil-and-gas and private-equity businessman, and championing public school reform. I wanted to hit the ground running with an ambitious agenda, and right after I was sworn in, on January 2, I was asked to make my case in a legislative session. After the session, we announced a reboot of the GLO, and we are completing that process, which is exciting. I feel confident that we’ve gained ground in those areas.

Now I want to look forward. In terms of 2016 and the next legislative session, my two priorities are pretty simple: One, to make this year the year of the veteran. As the chairman of the Veterans Land Board, which provides land and home loans to former members of the military, the biggest disappointment for me has been to see how overwhelming the statistics are. Only one in ten of our veterans is aware of the benefits available to them, and their rate of unemployment is astonishingly high. We have to do a better job.

BDS: And in a state with nearly 27 million people, Texas has approximately 1.7 million veterans?

GPB: That’s what our studies show. We are second in the country, behind only California. Our office manages eight health care facilities, and we are in the process of filing for a ninth. We manage four cemeteries as well. After the Central Texas floods last year, we raised the statutory limit for a vet to obtain a loan by 25 percent, and we provided interest-free loans temporarily for the next year.

The other thing I want to focus on is a coastal master plan, and I’ve been spending a lot of time in Washington, D.C., as a result. We have been framing a first-of-its-kind joint venture with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to develop a three- to five-year $20 million study to look at the critical vulnerabilities and risks along the Gulf Coast. Our coastline represents 40 percent of our state’s petrochemical production. With the export ban on crude oil and the emerging energy export terminal developments that we’re already seeing permitted on the coast, it’s time we got on it. That’s my focus for the next year.

BDS: Let’s break that down, starting with your outreach to veterans. You are a vet yourself, having served in Afghanistan, and there are a lot of overlapping agencies involved in reaching them. As you say, that can be confusing. How did you decide the best strategy for connecting with them?

GPB: When I returned from my mobilization after the surge of 2010, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported on the study I cited earlier. A very small percentage of veterans knew about the benefits available to them, and inside the veterans community, unemployment was above 5 percent. Then, in 2012, the Department of Veterans Affairs conducted a study that showed that 22 vets commit suicide every day. People debate that figure, but I’d say one suicide a year is too many. Regardless, the challenges were clear. When you look at the contributing factors to this high rate of suicide, which is the most alarming statistic of the three, you look at post-traumatic stress. For the eight facilities we manage, I wanted to create a first-of-its-kind program to help identify PTSD. I learned that touchstone communities had not trained our professionals to identify PTSD in our vets—and I don’t mean veterans from previous eras like Vietnam but vets from the 9/11 era. These issues can be overcome, but we’ve got to be open and honest about them, and we’ve got to raise the red flag and disassociate the stigma associated with mental health issues. We are implementing a program that helps our professionals identify those symptoms early on. I think this also comes down to collaboration with the federal VA. I was just in Washington, D.C., with the Democratic congressional delegation and the Republican delegation, and a lot of them remind me that not a lot of vets know about the reforms available through the federal VA. We want to collaborate with that office and the Texas Veterans Commission, which is administered by the Office of the Governor, and the veterans services offices in the state’s 254 counties. We have to get the message out.

BDS: But again, that’s a massive project. How do you go about that?

GPB: It’s easier said than done. It’s going to be a grassroots marketing campaign, and we’re looking at commissioning an RV to travel around the state, similar to what we did during my campaign. We want to get on base. We want to get out to visit Fort Bliss and Fort Hood and the vet community. We’ve hired the former garrison commander at Fort Hood, Colonel Matthew Elledge, a recipient of the Silver Star and the Bronze Star. He told me that 110 soldiers de-enlist on a daily basis, so we’ve got a huge challenge in Texas when you think about the vast amount of men and women coming out of service.

BDS: Are you the face of the tour bus?

GPB: [Laughs.] Our goal is to get out from Austin at least three times a month. We have strong military communities in El Paso, South Texas, and San Antonio. I’ll be on the bus with Matthew, and our goal will be to identify Texas veterans and celebrities who can help us get the message out.

BDS: Let’s talk about the coast. Last August Texas Monthly published a cover story that explored the challenges Galveston Island faces in protecting residents and infrastructure from another massive storm. There are a lot of plans out there. Which one do you think is best?

GPB: In the Galveston context, I’m optimistic about a six-county study that will be completed this summer and takes a comprehensive look at shoring up the biggest risks in the Galveston area. In fact, it floats the idea that your article discussed, the Ike Dike and the plans promoted by the SSPEED Center [the Severe Storm Prediction, Education, and Evacuation from Disasters Center at Rice University]. It also explores levee designs and organic ideas that could be pound for pound more effective. I don’t claim to be an engineer or an expert in design, but I do serve as the chair of that six-county study, and it contemplates just about any and all events in the next one hundred years. The modeling is extremely sophisticated. It doesn’t just take into account the storm surge from a hurricane event. It takes into account something like flooding from Central Texas that would come at the coast from an entirely different direction.

A project that size will need federal partnership, and with oil bottoming out at $30 a barrel, we’re looking at a constrained fiscal environment. So we’ll be the first ones to find creative ways to financially package that. What we can do in the meantime is solicit proposals from multiple engineering firms to design the first-ever Texas coastal master plan. The previous plan, which was mentioned in your story, only looks at Brazoria County up to Sabine Pass. That’s important, but this other study will examine the entire coast. We’ve got to look at Corpus; we’ve got to look at Brownsville. We hope to have completion of that by the end of this year as well. It will come forward with a lighter, faster, more nimble approach and will focus on marshland restoration and beach nourishment, which, in other Gulf states, have been found to be longer-term, more-cost-effective investments. You tie this in with the historic settlement from the BP Deep Water Horizon spill, and I believe that the Texas coast could be in a really good position if we do this the right way.

BDS: I’m no engineer either, but I realize that it will take money. Part of our story argued that Congress has shown that it’s in no mood to make that kind of investment to solve a problem before it happens.

GPB: I think you make the economic argument, which I’ve been telling our delegation. Louisiana, for example, spent north of $12 million on coastal infrastructure and obtained $14 billion in reimbursements from FEMA and the Corps of Engineers for redevelopment after Hurricane Katrina. New York and New Jersey invested $10 million in a plan and received $48 billion after Sandy. I think we need to be honest with the people who live on the coast and build businesses there—our public policy should not be based on reacting after a storm. When you look at the evidence, we’ve got to be proactive.

BDS: As you mentioned earlier, you initiated a reboot of the GLO over the summer. Why was that necessary? There was a lot of talk of “internal fiefdoms” and “silos” and that the threats to your agency were “internal.”

GPB: We are excited about that process, and we had buy-in from most of the rank and file in the system. The idea was to make our office more seamless and implement more private-sector principles. When I was sworn in, there were 21 functional areas of practice in the GLO, and on a weekly basis I would receive that many different reports. We synthesized that into three core areas: coastal, veterans issues, and asset enhancement. One of the most important functions of this office is to manage 13 million acres of state-owned land, and that means a different perspective on how we lease our minerals. We brought in different leadership from the private sector, from the military community, and from the engineering world to help lead this effort. In addition, one of the other things that I campaigned on was being a fiscal conservative and reducing the size and scope of government, and I wanted to follow through on that process.

BDS: And this wasn’t an arbitrary move? It wasn’t just cutting, say, 10 percent because it was a round number but because it would make the GLO more efficient and responsive?

GPB: Exactly. I think the evidence will show that. Consider a mineral lease that was just accomplished earlier this week online—our second online lease sale—that went for $2,492 an acre. At this time a year ago, oil was about three times the price it is now, and we averaged about $300 an acre. To get an eight-times-higher premium speaks to these changes. Look, I know that change can be challenging to a lot of folks, but there were changes that we had to make, and we’re doing this for the right reasons.

BDS: You also found yourself in the headlines last year over the Alamo, after your office took control of its operations from the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, which had managed the mission since 1905. The DRT has, in turn, sued, with a court date set for February 22.

GPB: When I came into office, I was briefed on what the Alamo could be from my predecessor, Jerry Patterson. A study had been commissioned that said if we didn’t replace core aspects of the structure, we would lose them, which I found to be unacceptable. I thought it was my responsibility to prioritize this for the legislative session, so I asked for an appropriation of $5 million for the structural integrity of the Alamo. As for the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, their management agreement had ended in March, and I thought we needed to take the Alamo in a new direction. I thank the Daughters for what they did in the twentieth century, but we needed to bring twenty-first-century principles to the Alamo’s daily management. The Legislature agreed and not only allowed the appropriation for the Alamo’s structural integrity but also provided funding north of $25 million for the implementation of a master plan to reimagine the visitor’s experience. As part of that vote of confidence, the Alamo Endowment [of which Bush is the chairman] became the day-to-day manager. The board comprises great Texas titans with incredible business experience, from Red McCombs to Ramona Bass to Gene Powell to Francisco Cigarroa. We’re going to partner with the City of San Antonio to further the aims of the master plan, which we hope to complete this year. Again, that’s the first of its kind. We also recently completed the acquisition of three buildings across the street from the plaza, including the Ripley’s Believe It or Not museum, which is important to admirers of the Alamo.

BDS: Because it’s such an eyesore?

GPB: I respect the entrepreneurs who are tenants of those buildings—I’m a small-business owner myself—but I think Texans recognize that we’ve got to do a better job of bringing a sense of deference to the shrine of our liberty. We have work to do with the congressional delegation as it relates to the federal building that actually sits in the middle of the original footprint of the Alamo. We are constantly visiting with adjacent landowners and tenants to reassess ways to reimagine the experience. This is the most visited site in the state of Texas, but our research shows that the average tourist spends eight minutes on the grounds of the Alamo. We’ve got to improve that.

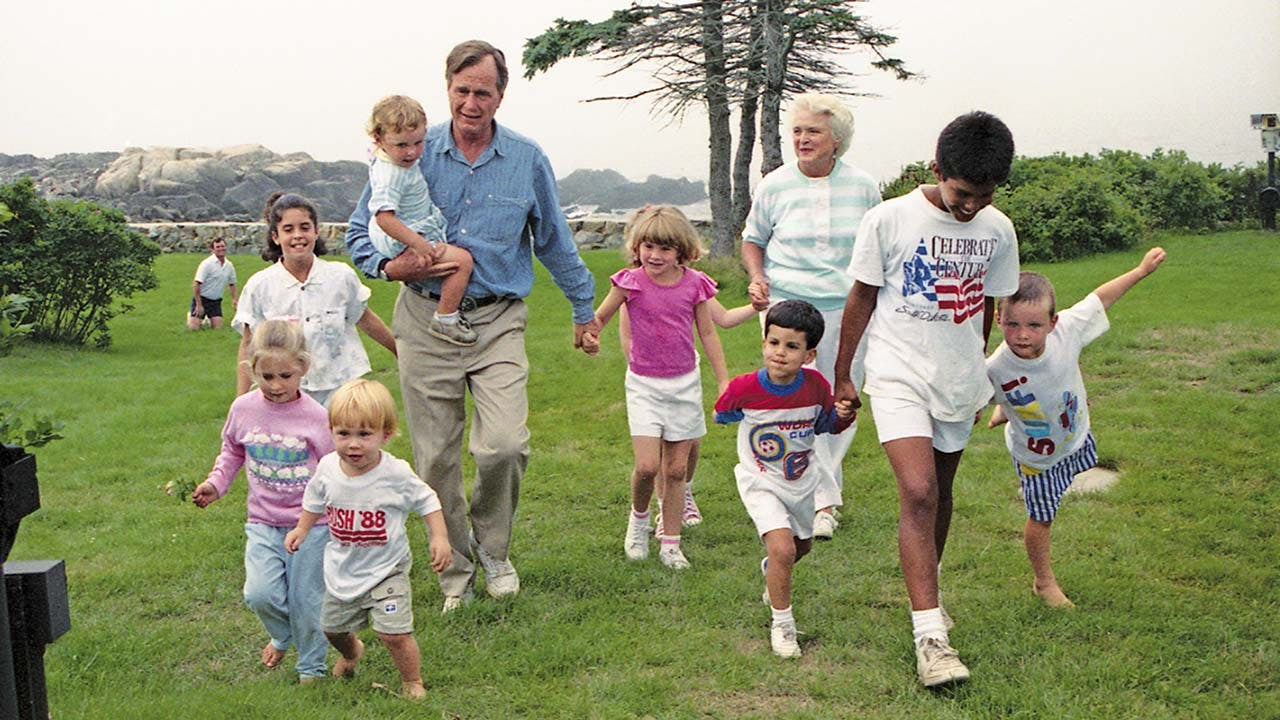

BDS: Let’s talk a little bit about your personal history and growing up Bush. I want to read you a letter your grandfather President George H. W. Bush wrote to journalist Hugh Sidey after you served as the master of ceremonies for your father’s second inauguration as governor, in 2003: “ ‘P,’ as we call him, has an amazing presence. . . . The way he looked, you felt he was in total command. He is a modest young man, a good student, and a wonderful kid in every way. He likes politics. In my view this guy will go a long way if he pursues a political path.” At what point did you have a sense that this was the right path for you?

GPB: It was coming back from Afghanistan. I’ve always had an interest in politics—I can’t deny that. I’ve worked on a variety of campaigns and fought for a variety of conservative causes for a long time. But it wasn’t until I came back from my military service that I realized I needed to devote myself to others. Of course, you quoted my personal idol and hero, and that would require asking him for his thoughts and advice. He’s always said that you have to do it for the right reasons and to make sure that your family is prepared.

BDS: What’s the best advice he’s given you? Or what’s the most important lesson you’ve taken from his career?

GPB: I think it’s the same advice he gave to my father and to my uncle: Make your own path and make your own name. Don’t feel like you are weighted to my policies or that you have to emulate my career—though I’ve tried to do that by serving in the Navy and going into the oil-and-gas business and attempting to be a major-league baseball player.

BDS: What is your first memory of what it meant to be a member of the Bush family?

GPB: I think I was three years old, at Houston’s Memorial Park, where my grandfather had a rally for the 1980 Texas primary. My family was living in Houston at that time, but I think being part of this family didn’t really hit me until then. In fact, that is one of my very first memories.

BDS: I was struck by something your father did earlier this week when he published a piece on Medium talking about your sister Noelle’s struggle with addiction. Is it difficult to deal with something like that—when a personal family issue becomes a part of the public conversation?

GPB: For me it isn’t. I know where my priorities stand, and it’s with my wife and my kids. It’s trying to be a loyal son and brother. Whether it’s my sister asking for help during her challenges or my dad asking for help with his campaign, I try my best, knowing that my responsibilities are to my family. I’ve always told my wife, Mandy, that if we ever cross a line, I’d be very happy back in the private sector. I am married to her; I am not married to this.

BDS: But as the media landscape changes and social media become omnipresent, the tone has definitely changed, I think. The middle has disappeared, and the political conversation always seems to be shrill.

GPB: It’s something I’m willing to take on. When you visit with folks from my grandfather’s generation, they say that he’d disagree with Tip O’Neill [a former Democratic speaker of the House], but at the end of the day they could have a beer together. I hope we don’t lose sight of that.

BDS: You don’t think we already have?

GPB: I think we haven’t in Texas. Based on my limited exposure during this last session, I think we have great comity in the House and the Senate, and I feel that we do work together to promote good public policy. In D.C., I think a lot of Texans believe that sometimes the issues have been too intractable. But I’m an optimist, and I think we’ll find a way around those problems.

BDS: Tell me what you think the future holds for Texas politics. Governor Greg Abbott is 58 years old. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick is 65. Where would you like to see the party go?

GPB: I’m privileged to serve in this current role, and I don’t view things in a generational context. Our state is truly remarkable, because we are leading this country with sound conservative principles. As long as we continue fighting for our ideals, we’ll move forward.

BDS: From a national perspective, you’ve been on the stump for your dad. How do you assess where his campaign is right now and where it goes from here?

GPB: I know it may sound contrarian, but this is the position that he wants to be in. The reason is that he has more endorsements from elected officials than any other presidential candidate, he’s got the financial resources, and he’s got a ground game. He’s flooding the zone, so to speak, in New Hampshire, and he’s built a campaign for the long term. He’s called himself a “joyful tortoise,” and he carries around little tortoises with him to remind himself and voters that the election won’t be won in Iowa or in New Hampshire.

BDS: Your grandfather did not win Iowa in 1988, so historically, at least, there’s a path forward.

GPB: We need a conservative messenger who can unite the clans of our party and drive home a victory against Hillary Clinton. That’s what I believe my dad can do.

BDS: You have self-identified as a Reagan Republican, but I’d like to know what you think it means to be a Bush Republican. Certainly the party has moved further to the right since your grandfather and your uncle were president, and that’s at least part of what your father is struggling with.

GPB: To be a Bush Republican is to have a message for all Texans, whether that’s leveraging some of the lessons from my uncle’s campaign for governor or from Governor Perry or other great Republican leaders. Those are the people I looked up to when I was coming of age politically in Texas. I think there are a lot of conservatives who look up to Ronald Reagan, and I think you can be the 80 percent friend of colleagues in the House and Senate and not be 20 percent enemies.

BDS: I’m obliged to ask how far you’d like to go in politics. Do you have a sense of where you’d like to take your public career?

GPB: I’ll try my best to be candid: there’s no harm in returning to the private sector after a certain amount of time if you think you’ve been able to effect change. I love being the commissioner of the General Land Office, and I love what our agency does, but despite carrying the family name, there’s nothing written in stone that says I have to run for higher office.