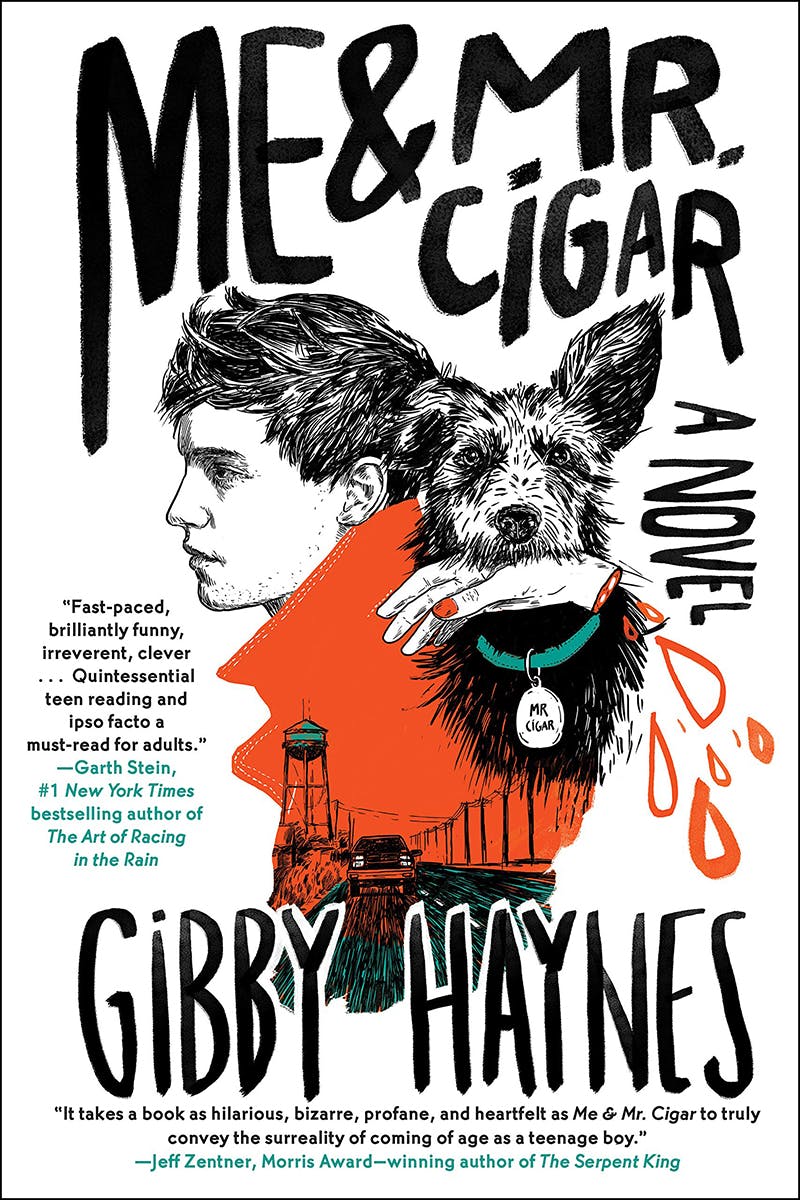

In the opening pages of Gibby Haynes’ YA debut novel, Me & Mr. Cigar, a twenty-pound dog dies from a kick to the head, digs his way out of the grave, and carries home a larva that blossoms into a flying dog that bites the hand clear off the narrator’s sister. Then things get really weird. And druggy. Before long, the narrator and his dog (Mr. Cigar) leave North Texas—where they’ve been hosting large-scale dance parties and dealing psychedelic drugs—to battle mysterious forces and free a hostage being held in New York City.

That the book is aimed at thirteen-year-olds might be a little surprising, yet maybe less so to readers who know Haynes from his slinging a similar cocktail of profane and funny across a four-decade run as the frontman for Butthole Surfers, the legendary post-punk Austin band that Texas Monthly once described as “the soundtrack to an acid-fried sideshow featuring a dancing naked woman, drums set aflame with lighter fluid, and bloody car-wreck movies.”

Me & Mr. Cigar is out today via Soho Teen, an imprint distributed by Penguin Random House. On the eve of its release, Haynes—who now lives in Brooklyn, New York—spoke with Texas Monthly about growing up in mid-sixties Dallas, setting Me & Mr. Cigar in Texas, and the uncertain future of Butthole Surfers.

This morning on CBS News, I saw Jason Reynolds—who was just named the Library of Congress’s national ambassador for young people’s literature—saying that kids today don’t have the time or attention span to wade through fifty pages of exposition. He said you’ve got to hook them right from the beginning. Your prologue is twenty pages of nonstop action. Was that by design?

This morning on CBS News, I saw Jason Reynolds—who was just named the Library of Congress’s national ambassador for young people’s literature—saying that kids today don’t have the time or attention span to wade through fifty pages of exposition. He said you’ve got to hook them right from the beginning. Your prologue is twenty pages of nonstop action. Was that by design?

Sure. But I’d argue the real hook begins three pages later, when all of a sudden there’s a dog carrying a bag in his mouth with $5,000 of MDMA. It’s definitely an action novel.

Did you know the whole time this was going to be young adult fiction?

Not at all. The prologue was a short story I wrote for an anthology, Stories of Ways and Means. The anthology was children’s stories written by musicians like Nick Cave and Tom Waits and illustrated by current cool artists. Then I was at a party at an art museum nearby my house and this person named Galaxy asked me if I would ever consider writing a book. I said I would not dis-consider it. I told her I’d consider considering it. And she told me that she has a friend that worked for Soho Teen. I got in touch and they asked to see something I’d written. I sent them the Mr. Cigar piece [titled The Next Big Thing] from the anthology and we decided to expand on that.

Even for teens, this is a pretty trippy drug story.

I know. That’s horrible.

It also makes sense coming from you.

Yeah, but there are consequences. As a father, I made sure there were consequences. But I didn’t want the tone to be too dear. I didn’t want to make it corny. Actually, I wanted to make it corny without being corny. And I wanted it to be heartfelt, but realistic and entertaining. There’s drugs, yes. But it’s not like the first-person shooter video games kids play today aren’t pretty hardcore. I’m at the dawning of my ten-year-old’s video game age, and it’s threatening his ability to think for himself. And have you read any of what they call Extreme YA? It’s less story and way more gory.

But is this still going to be an awkward fit for a lot of school libraries?

No. Do you know how influential and important Texas librarians are? Apparently they’re excited about it and think this is the kind of thing that’s good for the hard-to-reach kids, which makes me happy.

They’d rather kids be reading something than not.

Yeah. They’d rather kids be reading garbage than nothing at all.

In a note to readers you say, ‘I would hope that a young person reading this book would acknowledge the craziness of their own world—to flee from it as well as embrace it.’ You grew up in Dallas in the sixties. Is this even a weirder time for kids than that was?

It’s a weird time for kids. But the sixties was the assassination decade. And the seventies were the serial killer decade that started with Manson and ended with Bundy, peppered by Hillside Strangler and Son of Sam. My favorite serial killers were the Texas ones. They’d just started digging up bodies, and quit when they finally broke the record. They were like, “We got enough. We’re on the map!”

It’s probably not lost on you that a kid reading this today probably doesn’t know the first thing about the Butthole Surfers.

I love that.

That they come to it with no baggage?

Exactly. Early on, the glory of being a band was in playing in front of an audience that’s never seen you before. And as we performed more and got more popular, it was a bummer that you couldn’t do that anymore. It was performing for a seasoned audience that became a drag.

I’m afraid of the reviews though. Have you seen the reviews for the latest Sean Penn book? It’s gotten so skewered. “160 pages of ass-showing” was my favorite review of it.

So you’re afraid the people who are going to review do in fact know the Butthole Surfers?

Yes. Very much so.

How important was it to you that this story be set in Texas?

I figured that I could write more honestly if I could revisit my teen years. So there’s cicadas and fireflies. But apparently the mountain range in North Texas I write about doesn’t exist. Don’t tell anybody?

Things got weird for you once you got to Austin, right? You didn’t necessarily have crazy teenage years.

Not in terms of divorced parents, testicular cancer, and a car wreck that took my left leg. I didn’t have that kind of shit. But the times were weird. I was in second grade when I went over to my cousin’s house in Oak Cliff and he told me there was no such thing as Santa Claus. I went home that night and asked my father to come to my room. I pressed him hard for an answer and finally he said, “You’re right. It’s impossible. There’s no such thing as Santa Claus.” And I immediately said, “Well, am I going to die in Vietnam?”

Your father was the beloved Dallas-area television host Mr. Peppermint. Did Mr. Peppermint ever meet Mr. Rogers?

No. But who was the dinosaur?

Barney?

Yeah. I heard my dad say on several occasions, “Fuck Barney.” My dad also had a competitor in the Dallas-Fort Worth area—Slam Bang Theater, hosted by Icky Twerp. They definitely had a rivalry. My dad kicked his ass in the rating and Icky held onto that. But if you have any opportunity to see clips of Icky Twerp’s show on YouTube, a show conceived by young theater people, you’ll see how dark it was. That was my dad’s competition and my dad was Mr. Rogers minus the homoerotic element. That would not have floated in North Texas at the time.

Last year, when Daniel Johnston died, a video from YouTube made the rounds of you guys talking backstage in the early nineties, and you’re really patient with him.

Oh, everybody loved Daniel. He was eccentric from day one, even before the nervous breakdown. So you kind of had to hold him dearly from the beginning. And it was great to be part of that. It was really great to have that young Daniel Johnston experience. He was gorgeous. And he was loving and curious. He was a genius and just really fun to hang out with. Those were good days.

You haven’t released music since a seven-inch single you made with Jack White in 2013. Are you just not interested?

No, not that much. I’ve been looking for something else. I’ve done quite a bit of graphic art, which is fun. And I want to write another book.

What is it about music that doesn’t do it for you anymore?

The main thing is that I don’t live with my bros. I live up here in New York and they’re down in Texas and that’s who I make music with. We might make more music, but we weren’t that much of a musical entity. I don’t want to say it grandiosely, but we were more than music. We weren’t just music. I’ll put it that way.

And that would be hard to recapture now?

Yeah. Now everybody does what we did then that was new. We would have crazy videos behind us, and now you don’t have to go to the University of Texas Film Library to find out-of-control videos. They’re on YouTube and everybody can see him.

Would people going to Coachella now know what to make of the Butthole Surfers?

No. They’d probably think we were a thud—like Flaming Lips. Our time is gone. But it lasted quite a long time. We had a good run.

Do you think about legacy?

No, but I think about why other people think about legacy. Who cares what happens after you die?

What would make this book a success? What’s that look like for you?

Seventeen weeks on the New York Times best-seller list, he says without hesitation.

And outside of that?

I’d like people to come to the events. I have one with my buddy Jim Jarmusch this week in New York. And there’s supposed to be a D.C. event with Ian MacKaye. We’ve had a tough time nailing that down though. Maybe I have a bad name in D.C.? And D.C. is the mother of woke. It’s the epicenter of woke. It’s where they have all the woke rallies. And I’m woke, for Christ’s sake. I’m woke as shit. I don’t have a gun. I voted for [Hillary Clinton]. But I do want to own a sniper rifle for some reason. Just to shoot at things from five hundred yards away—targets, but not targets shaped like humans.

That’s a woke distinction.

It is. Also, you know what’s really great? The first bookstore that said, “Yeah, come on in and have an event,” was the City Lights bookstore in San Francisco.

Is that surprising?

No. But Lawrence Ferlinghetti owns it and is still alive. He’s like 120 years old or something. I know he’s not going to show up at the gig, but I can at least have a good time thinking about it.

- More About:

- Music

- Books

- Austin Music