On February 22, 1969, a Marine company was on patrol in the jungles of the A Shau Valley when a mortar round landed in the midst of the command group and severely injured the platoon leader and others. Lee Roy Herron, a Lubbock native, took charge.

Terry Presgrove, a Marine injured by the mortar’s fragments, remembered Herron’s response.

“Lee came up to me shortly after the mortar had hit in our midst. I was lying on my back on top of another wounded Marine,” said Presgrove. Screaming above the roar of the firefight, “Lee knelt down and asked me where my battle dressing was, seeing that I was bleeding.”

“We exchanged a few words, then he used the only four-letter word I ever heard him say: ‘Damn.’ He was visibly upset by the carnage, but had that look of determination and firm resolve to do his duty. Our eyes met, communicating without speaking the knowledge that we were in a serious jam. He patted me on the head and quickly moved off toward the dug-in enemy.”

Herron’s calmness and determination surprised no one who knew him. His valor was an ordinary miracle. He performed without complaint or excuse.

I first met Lee Roy in 1957 in the seventh grade at Matthews Junior High School on Lubbock’s north side. His parents were like mine: conservative, hardworking, and thrifty. They lived through the Great Depression and saw education as the primary means for their children to better themselves.

We became fast friends. We were rivals in scholastics, athletics, leadership awards, spelling bees, and even the John F. Kennedy National Fitness Test. By the eighth grade, our friendly competitiveness was so well known that it emerged in the ninth graders’ “Last Will and Testament.” The document stated that Bobby Clark and Kenny Allred “would like to leave their dueling swords to Lee Roy Herron and David Nelson. They’ll be needing them.”

Herron received the Daughters of the American Revolution Citizenship award and I was runner-up. He deserved it. He also was senior class president and class favorite. He deserved those awards too. Once, in a softball-throwing contest, I was leading the contest with a throw of 85 yards—then Herron threw the ball 90 yards. Years later I thought back to that contest when I learned that Lee Roy had destroyed a machine gun bunker in Vietnam by hurling hand grenades at the enemy emplacement.

In the fall of 1962, we knew we would soon register for the draft. The Bay of Pigs disaster occurred and the Cuban Missile Crisis was upon us. Herron and I had our P. E. class late in the morning, and one day he was missing when the roll was called. But soon Herron ran onto the athletic field toward me, hollering, “David, we may be going to war with Russia!”

His glee surprised me. Herron once again was fearless. He was a Marine well before he knew what that meant. Herron and I began college life in 1963 at Texas Technological College, now Texas Tech University. By then, both of us had been sobered by life in general, but especially following the assassination of President Kennedy. We focused on scholastics and considered our military commitments. Herron majored in government and I in pre-law.

Herron joined the Marine officer program, called the Platoon Leaders Class. He spent six weeks in PLC training near Quantico, Virginia, in 1964, and by the next year President Johnson was sending thousands of troops into Vietnam. I needed to do something about my military obligation. I sought Herron’s advice. He recommended the Marines. I joined the Corps on October 21, 1965.

On June 13, 1966, Herron and I flew to Washington, D.C., where some “friendly” Marines met us, and then transported us 35 miles south to Quantico. On the flight up, the plane had lurched and Herron had spilled coffee on his shirt. He was upset the rest of the flight, thinking he would not be able to appear neatly dressed to the Marines who would meet us. Not surprisingly, a gung-ho Lee Roy finished first in his class; company honor man. I was happy just to complete the tough training course and graduate.

I was accepted into a Marine Corps law program. I preferred to do my military service as a judge advocate (JAG officer). Herron was determined to serve as an infantry officer. We parted ways, with Herron heading for Vietnam. Newly married, I began law school at Southern Methodist University. Herron left Quantico for Monterey, California, and defense language school. He called me from there to tell me exciting news: “Guess what, David? Danelle Davis and I are getting married. You remember her, don’t you?” He asked, “Can you come to our wedding May 4th in Lubbock?” I reluctantly said I could not, as I would be in the middle of law school final exams. Not attending Herron’s wedding is one of my deepest regrets.

Herron did extremely well in military defense language school. His mother told me that he was offered the opportunity to serve in Washington, D.C. as a Vietnamese language translator. But you know enough about Herron now to know that he refused the Washington, D.C. opportunity. On December 30, 1968, he arrived in Vietnam. By then he was a first lieutenant and was assigned to Headquarters & Service Company, Third Marine Division, at the large Vandegrift Combat Base. He insisted that he be transferred from Vandegrift to the front lines. That request was honored and he was sent to Alpha Company, First Battalion, Ninth Marines, Third Marine Division.

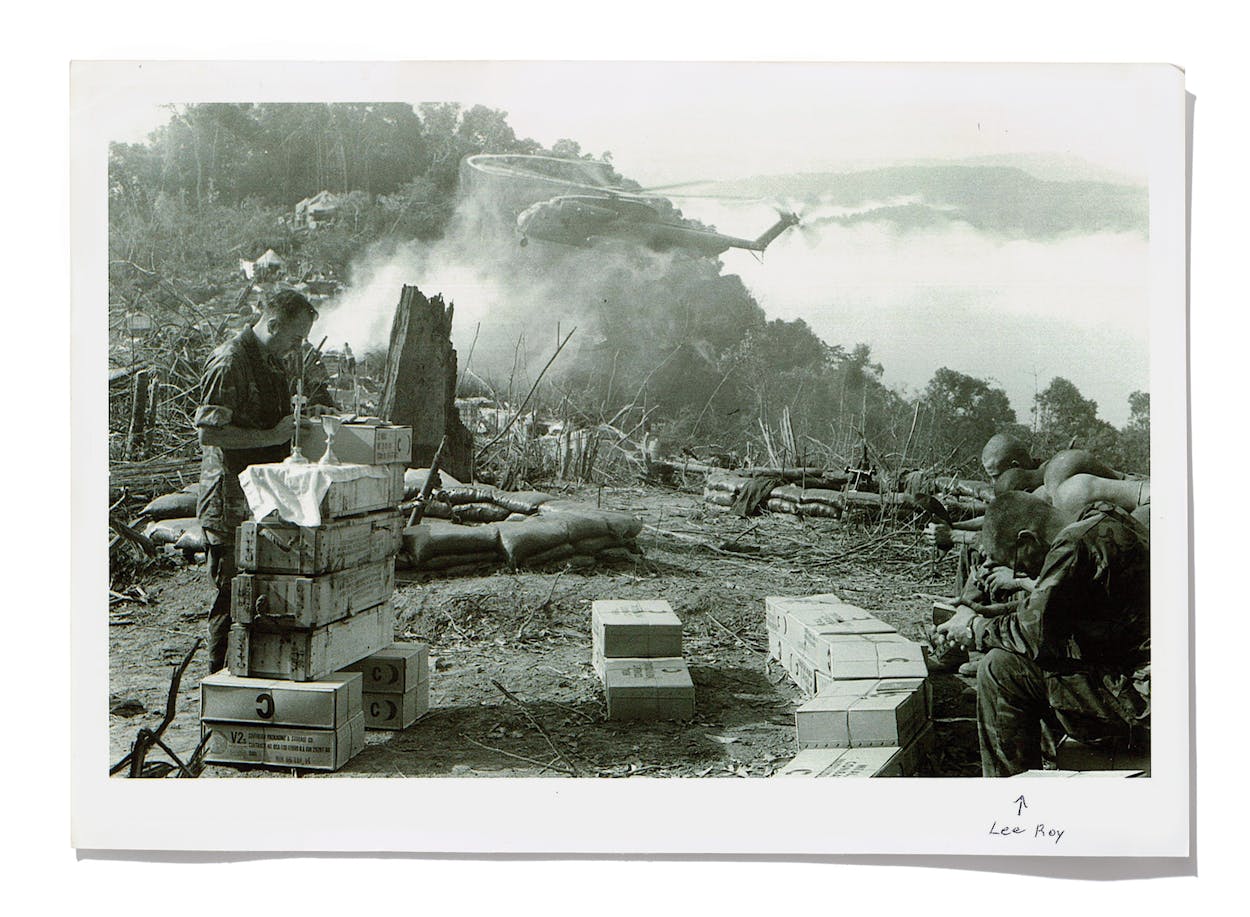

Even in Vietnam, he maintained his strong faith in God’s purpose and destiny for him. On Sunday, January 26, 1969, Herron flagged down a resupply helicopter going over ten miles of enemy territory from his assigned Fire Support Base Shiloh to Fire Support Base Razor so he could attend a makeshift church service held in a bomb crater. He is the only person I know of who would fly over enemy territory just to attend church.

A Marine photographer caught the image of that service in an iconic photograph that is now displayed at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, on a wall dedicated to chaplain service in Vietnam. Herron appears in the right foreground of that photo, head bowed and holding a small Bible in his left hand.

Herron’s excitement with being in a combat situation was shown in a February 18, 1969 letter to Charles Lance:

“Don’t spread this around – but ole Herron is right in the middle of a slam-bang, ROCK –‘EM , SOCK – ‘EM operation. The entire regiment is within 5,000 m of Laos; I’m presently 2,500 m. This OP is designed to stop the flow of supplies from Laos down South to the A Shau Valley. According to the ‘ole hands,’ we’ve hit more resistance on this OP than the battalion has encountered since Khe Sanh (about a year ago).

“I’m ‘used to’ fire fights by now. It’s amazing how one adapts to this ‘madness’ – the blood, etc. doesn’t bother me at all. Generally speaking, we’re kicking hell out of NVA. Regiment has broken their code, and we know that they are really hurting. Between a regiment of Marines, AIR, and arty – they can either fight and die or retreat. So far they have been fighting. Our body count keeps mounting.

“Your buddy is truly a veteran by now. I’ve been shot at, mortared at, RPG’ed (type of rocket) at, booby trapped at. Everything but enemy artillery. However, the worst thing so far has been the lack of water. Yesterday we had to move 2,000 meters during the hottest part of the day, dig in, etc. –ALL without water! That was HELL! We even had people lying in the open during a firefight – they were so tired and dehydrated that they couldn’t or wouldn’t move. Thank God, today we have some water – therefore, we’re 3X better off.”

On February 22, 1969, Alpha Company was ambushed and Lee Roy Herron was killed in that same A Shau Valley jungle, while heroically saving the lives of numerous other Marines. For his actions he received the Navy Cross posthumously. Here is how Herron’s company commander, then First Lieutenant Wesley Fox (who received the Medal of Honor for his actions in the same battle), described Herron’s death to his widow Danelle, in a March 12, 1969 letter:

“I am sorry that this is so late. The reason is Alpha company is still in the bush and operating on the Laotian border close to where Lee died. On 22 February our company was on patrol and moved into the attack on a known North Vietnamese position. They were in bunkers and had a good machine gun defense. My command group was hit by a mortar round which also wounded the 2nd Platoon leader.

“Lee took command of the 2nd Rifle Platoon and led them in the attack on the machine gun positions. His last words to his radio operator were ‘I am going to get that gun’ and with that he jumped up firing and throwing hand grenades until he did knock out the gun position.” A supporting enemy machine gun then hit Lee high in the chest and he died instantly.

“Lee loved you very much as he spoke of you often and always had your picture handy. He loved God and his country and for these three things he died. He died a Marine hero and he has been put in for our country’s highest medal, the Medal of Honor. I know this will not ease your loss in the least but you can expect to be called on to receive this for Lee.”

When I heard then retired Colonel Wesley Fox speak about the 1969 battle on August 2, 1997, Fox elaborated on the circumstances of Herron’s death. He told me that while Herron was getting close to the machine gun bunker he destroyed, there was a heavy mist and cloud cover. As Herron prepared to go after the final machine gun bunker, the mist and cloud cover suddenly lifted and Herron was in plain view in the sunlight. He was killed by gunfire from the remaining machine gun bunker. However, since the cloud cover had lifted, Fox was then able to call in air support to destroy that final machine gun bunker. The battle was finally over.

I have thought many times that if the heavy mist and cloud cover had remained just minutes longer, Herron might have been able to destroy both the first bunker and the one that got to him first. But as Herron’s mother Lorea told me years after her only son’s death, “He died doing what he always wanted to do—defending his country.” She did not exhibit any bitterness, perhaps due in part to Herron’s encouraging words in a “just in case” letter he wrote his parents just before leaving for Vietnam:

“When you read this I’ll be dead or missing in action. This letter is my way of saying goodbye and is a final thank you for being such wonderful parents. Please believe me when I say that I have no regrets. I was given the best parents that a child could have. I was taught to love God and our country, and since it was God’s will that I die young, I’m proud to die as a Marine defending America.”