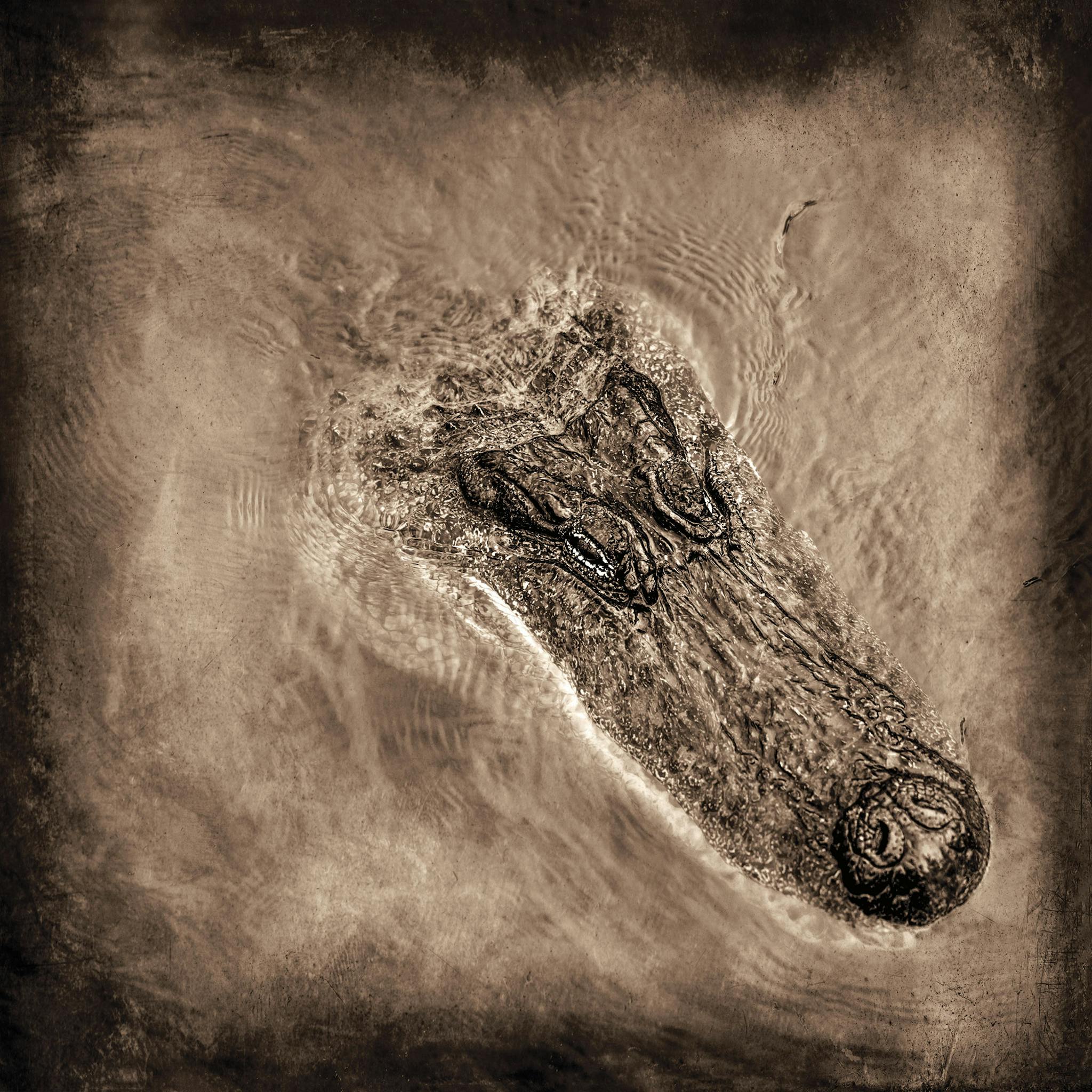

The Big Thicket National Preserve is one of the wildest and least accessible parts of Texas. Sprawling across more than 113,000 acres of East Texas, the mossy and mysterious expanse encompasses swamps, forests, savannahs, and plains—“as if almost all nature rushed to this one spot,” observed one travel writer. But the Thicket is perhaps best known for its wetlands, a Southern Gothic landscape of shallow marshes, bald cypress trees, and primordial-looking alligators.

Photographer Keith Carter has been fascinated with the Big Thicket since his childhood in nearby Beaumont. In high school, he would explore the boggy terrain on hunting expeditions with his friends. “I wasn’t a big hunter, but I liked to go with them, and they would take me out to places I’d never been to,” Carter recalled. “It was the murkiness, the mystery of it all. I just thought it was like being on an entirely different planet.”

Now 75, Carter still lives in Beaumont and still loves visiting the Thicket. His new book, Ghostlight (out this month from the University of Texas Press), encompasses more than a hundred monochrome photographs taken in the preserve over the past decade. Prefaced with a haunting original short story by Austin author Bret Anthony Johnston, the book conveys the strange allure of these brackish backwaters and their biological menagerie. Captured during countless expeditions—by foot, by canoe, and once by airboat—the photographs document the Thicket’s bewildering variety of plant and animal life. More than three hundred bird species, fifty kinds of reptiles, thirty varieties of orchid, and four of North America’s five carnivorous plants reside at this rich ecological crossroads.

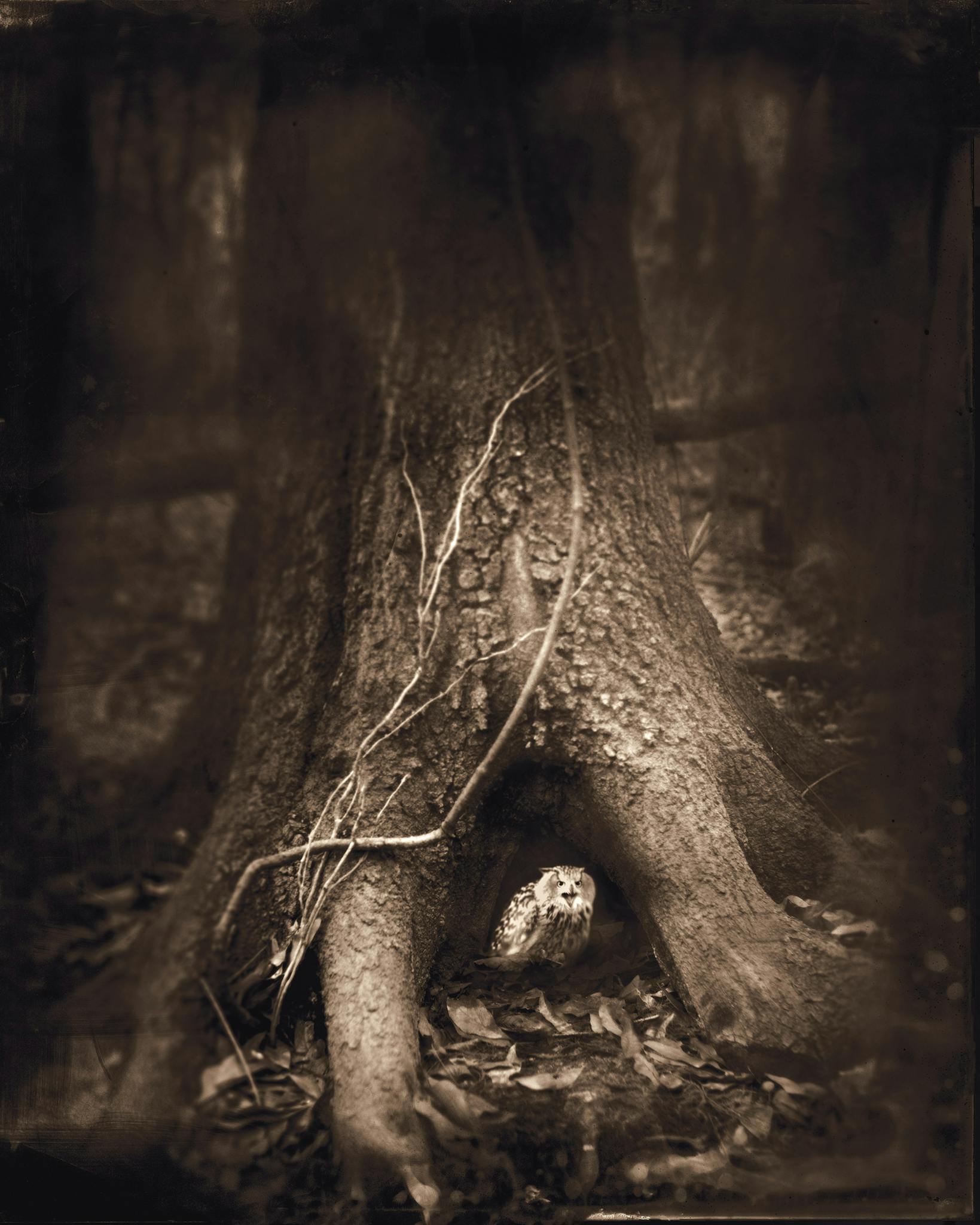

As so often in his work, though, Carter is less interested in documentary verisimilitude than in evoking the spirit of a place. To get what he wants, he experiments with a variety of cameras and techniques ranging across the history of the medium, from the nineteenth-century wet-plate collodion process to Adobe Photoshop. The first photograph in the book is a digital composite of two images, one made with a pinhole camera by Carter’s longtime assistant Cathy Spence, and one taken by Carter with a traditional lens. The final image shows a car navigating a backwoods road beneath a riotously starry sky. It’s a scene you won’t find in nature—only in art.

Carter’s playful approach can be seen in nearly every photograph. Drawing from a deep bag of tricks, he can make photographs that resemble still-life paintings, chiaroscuro portraits, or carefully etched Japanese woodblock prints. His sepia-toned images have a timeless quality emphasized by their vignetting—an old-fashioned darkroom technique that subtly darkens the edges of a print. “As I’ve gotten older, I really have veered away from perfect precision,” Carter told me. “I know how to make those kind of images, but they don’t sustain me as much as something that harkens back to the history of photography.”

Carter’s magical-realist style is a good match for his latest subject. The Thicket has long inspired tales of the supernatural, from ghost stories to Bigfoot sightings. The book’s title, Ghostlight, is a reference to the so-called Light of Saratoga, the lesser-known East Texas analogue to the Marfa lights. The short story that opens the book is narrated from beyond the grave by a former Big Thicket dweller who grew up hearing stories of spirits, fairies, and witches.

East Texas wetlands may all look the same to an outsider, but locals divide them into swamps, marshes, bogs, fens, and baygalls, each with its own characteristic qualities. Baygalls—the name derives from the sweetbay magnolia and sweet gallberry trees that grow there—have always been Carter’s favorites. He’s fond of their gloomy, even Halloween-esque atmosphere. “The waters are dark, almost tea-stained, and that comes from the vegetation,” he said. “If you stick your hand in there, you can see maybe a foot, and then everything disappears.”

As Carter continued to rhapsodize about the baygalls, he seemed, obliquely, to be describing his own photography. “You can say they aren’t pretty, and they don’t lend themselves to attractive pictures,” he said. “They have a dark and mysterious beauty. It’s more about what you can’t see than what you can see—the possibilities of what you can’t see.”

- More About:

- Books

- East Texas