On a lawn at the Retreat at Balcones Springs, a summer camp–themed Hill Country event space, a group of guests dressed in gowns, cowboy hats, and other regalia were eating barbecue at red gingham–covered picnic tables while tunes by Willie Nelson and Lefty Frizzell played over the speakers. It was spring 2019 and the guests had come for the inaugural Camp TAZO, a three-day adult camp hosted by TAZO Tea Company, which had invited participants from all over the country to come together to “brew the unexpected.” Even some of the barbecue sauce was TAZO-infused.

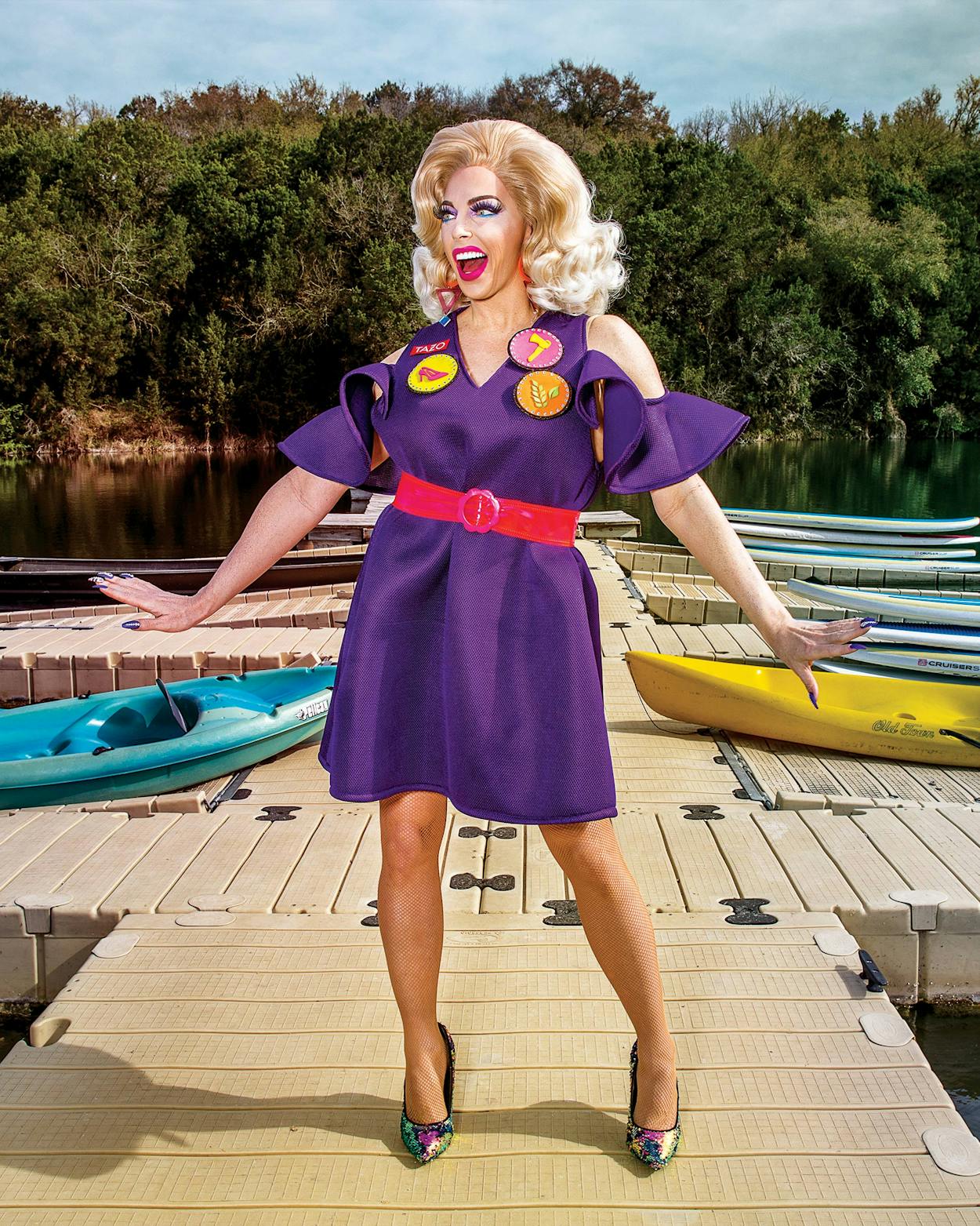

Sauntering among the attendees was Camp TAZO’s “director”—part emcee, part life coach—a drag queen named Alyssa Edwards. Edwards is five foot nine, but six one in heels, her dancer’s gams rising out of size-ten platforms. She’d highlighted and contoured her pale, freckled cheekbones until they looked sharp enough to cut glass, and she wore inch-long false eyelashes. Her platinum bouffant took seriously the old adage about hair height and God. She was a hard-to-miss bombshell.

Edwards caught the attention of eleven-year-old Trinity Sager, who was visiting with her family as part of Project Sanctuary, a charity that hosts therapeutic retreats for military families. Trinity asked her parents, Rob and Judy Sager, if she could introduce herself to Edwards, and the Sagers found someone who looked likely to be in charge to ask Edwards if she would be willing to meet a young fan. When she responded with enthusiasm, Rob Sager led the way.

Edwards took in Rob, a barrel-chested Marine veteran with a graying goatee. “Hi, I’m Justin,” she said, deploying her offstage name. She extended her violet press-on nails to shake the hands of both parents while Trinity and her ten-year-old brother, Caleb, stood nervously nearby.

Edwards, forty, is a world-famous drag queen, star of a season of the reality competition show RuPaul’s Drag Race and, later, a season of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars. Though she didn’t win either season, she remains one of the franchise’s biggest success stories (she recently returned to All Stars as a “lip sync assassin”). She has 1.8 million Instagram followers and ranked fifth on Vulture’s 2019 list of the hundred most powerful drag queens in America. She’s known for her bright outfits, big hair, and sprightly dance moves. She is beloved for her country-fried malapropisms and what one fellow contestant referred to as her “off-the-cuff-buffoonery responses.” She sells her own makeup palette, has her own signature sound—the tongue pop—and has headlined shows all over the United States, Canada, and Europe, and as far away as Australia. But Trinity Sager had recognized Edwards from the Netflix reality series Dancing Queen. The show followed the students of an elite children’s dance studio, Beyond Belief Dance Company, then located in Mesquite. The dance company is owned and operated by the man beneath the makeup, Justin Johnson.

Trinity stayed silent while Edwards chatted with her parents. “Let’s take a picture! Come on, you guys,” Edwards suddenly cooed, waving Trinity and her brother over. Edwards wrapped her arms around both kids and gave a thumbs-up to the camera while Rob snapped the shot. Then the Sagers said goodbye and headed back to their room. As soon as Edwards was out of earshot, Caleb turned to his family and said, “She’s tall.”

Once they were gone, Edwards turned her attention back to Camp TAZO. She was off to host the night’s big activity, a “hidden talent” show, in the nearby pavilion. There were glittering streamers, club music, and luxuriant outfits: one guest wore an antique birdcage for a hat; another camper wore a full Prince Charming costume, with puffy Elizabethan sleeves, a crown, and a pair of big, sparkly heels that would later be gifted to Edwards in tribute. Fueled by corporate-sponsored tea, campers laughed, cheered, and even shed a few tears as they watched their newfound BFFs dance, sing, mime, and joke onstage.

At the end of the night, after a rousing dance-and-sing-along to the ABBA hit “Dancing Queen,” Edwards stood among the crowd. Under the sanguine lighting of the pavilion, she turned earnest. “For a lot of years, I was so unaware—almost lost, or in the dark—and then I put a wig on for the first time,” Edwards told her audience. “It gave me the courage,” she added. “It was kind of like my cape, to be a superhero.”

A few decades ago, a collaboration between a drag queen and a multinational conglomerate like Unilever, which owns TAZO, would have been unlikely. But since RuPaul began building the Drag Race empire, mainstream appreciation for drag, once a subversive underground art form, has swelled. In 2018, RuPaul’s DragCon, a series of multiday conventions in New York and Los Angeles (and, this year, in London), attracted around 100,000 visitors and netted a reported $8 million in revenue. Drag queens have starred in international Drag Race spin-offs and have appeared in Golden Globe–nominated films, scripted cable shows, and a new reality franchise that aired on HBO this year.

Drag has entered a golden age, and Alyssa Edwards is at the heart of it.

On a Thursday evening in November, Beyond Belief was as busy as a mall food court on a pre-pandemic Saturday afternoon. All three of the studio’s practice rooms were occupied by groups rehearsing their routines. The small foyer was full of moms, talking about their kids. Even the hallway was packed: half a dozen children under seven held on to a ballet barre and practiced their foot positions beneath plaques and collages celebrating Beyond Belief’s successes.

Johnson hotfooted among them all. He was wearing his studio clothes: mustard yellow track pants, all-black Adidas sneakers, and a black tank top that exposed a tattoo on his right bicep. His posture was impeccable, and even without Alyssa Edwards’s makeup, his freckled cheekbones and blue-green eyes were striking. He’d pop his head into the main office to confer with office manager Dawn Robbins, then would run out to the lobby to ask the moms something. He spent most of his time in the back room, walking the youngest group through a new routine. The students, all girls, wore white plush gloves and danced to a mashup that included a Lizzo remix in which Minnie Mouse sings, “I just took a DNA test, turns out I’m one hundred percent that mouse.” Johnson often leaped onto the dance floor to demonstrate the moves: “A ding and a ding and a-open and a ding,” he said on-beat as he guided the kids through the hand motions. When he was at rest, he perched on an elevated prop trellis, decorated with huge red roses, in the back of the room.

“His energy level is just—it’s crazy,” says Robbins, who was succeeded as office manager by Kelly Epton in early 2020. Robbins had worked at Beyond Belief since its early days: she first met Johnson in 2007, when he started teaching her youngest daughter, Celeste, who now dances with choreographer Marie Chouinard in Canada and teaches a few summer classes at Beyond Belief. “He’ll stay up until one or two in the morning talking to dance moms, then bop up at six a.m. and go work out and go to the bank. He must be driving like a maniac all over town. He’ll call me and go, ‘I’ve done this and this and this,’ and I’ll say, ‘Whoa, I’m just drinking my morning coffee.’ ”

Alyssa Edwards is famous all over the world, but Johnson feels most at home while teaching at Beyond Belief, a business he’s been building since 2004, years before he first competed on RuPaul’s Drag Race. Johnson opened Beyond Belief in Mesquite, where he grew up, but in August 2018 he moved the studio to a larger location in a nondescript Garland office park on the edge of Lake Ray Hubbard. The company is the reason he’s never really considered moving to New York or Los Angeles, cities that other RPDR alums have flocked to after their big breaks. “Alyssa is larger than life and fabulous,” Johnson says, “but I think I’m a better teacher and choreographer than performer.”

Around 9 p.m., as the studio was clearing out, Johnson called Kirra Lee, a ten-year-old dancer, into the windowless back room he and Robbins used as an office. He asked Kirra to take a seat on “the good couch.” He wanted to check in quickly before she went home with her mother, Vanessa Lee, who was standing nearby.

“I want you to know that everybody here believes in your ability. Every. Single. Teacher. Here,” Johnson told Kirra, hunching over slightly so he could make more direct eye contact with her.

“I want you to get out of your head when you’re given a critique,” he continued. “You’re here because you want to be critiqued. Ultimately, for the bigger goal: not to win just competitions, but to win in life.” He asked Kirra what grade, out of one hundred, she would give herself for the season.

“Um, eighty-five?” she said apprehensively, after reassurances from Johnson, her mother, and Robbins that there was no wrong answer.

“Okay,” replied Johnson. “Is that the grade you want to have? You know that score can’t win with a solo, right? Okay, so you gotta say, ‘Okay, what can I do to get a ninety or above?’ That’s just five more points.” He continued, explaining that critiques were good; if your director didn’t notice you, on the other hand, that would be a bigger problem. Johnson told Kirra how blessed she was that her mom came to all her dance practices; his mother had not been able to do the same. Kirra, he said, was the only person standing in Kirra’s way. After a high five, Johnson told her, “All right, thank you, baby.” Then he turned to her mother, offering to help if she ever needed him to give Kirra a ride home. “I know you got other kids doing other things and I don’t mind,” he said.

Johnson considers many of the dance moms family. A few years ago, after he bought his first home, in a gated community just outside Mesquite, they helped him move out of the Oak Lawn apartment he’d lived in for years. They come to his house parties and his rec league games. “He started playing in this gay kickball league on Saturday mornings,” says one dancer’s mother, whose daughter started dancing with Beyond Belief in 2018. “He went to one game and then we were all, ‘Well, we’re coming! When do you play?’ Then, of course, we show up in full T-shirts, pom-poms, kids—everybody. They’re like, ‘Justin brings a family.’ ”

“I’ve watched my daughter meet those expectations that I would never have thought she’d be able to meet. I would have given you an excuse before.”

She initially balked at Johnson’s teaching style, she explains. He doesn’t coddle, and he isn’t stingy with critiques. He holds his students to high standards, but only because he’s certain they can meet them. “His expectations—as a mom, you want to say they’re not realistic. But how do you know they’re not realistic? Because I’ve watched my daughter meet those expectations that I would never have thought she’d be able to meet. I would have given you an excuse before.”

Johnson likes to say, “If you can make it at this studio, you’re going to be ready for the professional world.” In addition to dance technique, he teaches his students how they—like him—can build a career from their creative passions, if that’s what they want. At the very least, says Andrea Canterbury, whose daughter Riley has danced with Johnson since she was eight, “I mean, good gosh, they’ll have something great on their résumé.”

Some of Johnson’s young students have already begun to capitalize on the platform Dancing Queen provided them. Since Netflix released the show, in 2018, some students have acquired not-insubstantial social media followings, which in almost any industry is leverage for gigs and sponsorships. Riley, for example, has almost 11,000 Instagram followers. Another student, Kiana Sanderson, who struggled with Johnson’s often harsh criticism on Dancing Queen, has almost as many. Now nineteen, she just finished her freshman year at Southern Methodist University, in Dallas, and she helps teach some of the younger students at Beyond Belief. She’s already done some sponsored posts repping Be You Brands apparel, a clothing line for kids and teenagers, whose designs often involve rhinestones and statements like “Girls rule.”

Kiana’s little sister, Leigha, who is thirteen years old, is also a “Be You Boss,” who occasionally advertises products to her 10,700 thousand Instagram followers. Leigha was born with a lipoma on her spine; she has already had three spinal surgeries and lives with chronic pain and spina bifida. Because of the location of the tumor, she has had twenty bladder surgeries. Her parents started homeschooling her after she missed ninety days of third grade, and since then the studio has become her favorite place to be. Johnson allows her to come into the studio early if she needs to, and sometimes he gives her one-on-one instruction. “It’s kind of a place for me to escape,” Leigha says. “When I’m having a bunch of struggles at home or with my health, I just kind of go to dance and forget about everything and dance my heart out.”

Johnson has been teaching kids to dance since he was still technically a kid studying dance. Back in the late nineties, when he was at West Mesquite High School, Johnson started volunteering as an instructor and choreographer with the local peewee drill team. “That’s a huge commitment,” he recalls, with daily practices from six to eight in the evening and games on Saturday afternoons. “But I was out there running those drill teams and running that field!”

He’d been fascinated by the drill team since he was a little kid, watching his sisters at their practices, wishing he could join. He was one of the oldest of seven kids in a working-class family. He describes his mother as “the wind beneath my wings” and his father as “very, very masculine.” Johnson was a shy, creative boy. He had no interest in sports, but loved The Wizard of Oz, and he would sit silently, glued to the television set, whenever his mother put it on. Somewhere in the Johnson family archives exists an old VHS recording of a ten- or eleven-year-old Johnson running around in the front yard in overalls and no shirt, waving a ribbon through the air, singing Rod Stewart’s “Forever Young” at the top of his lungs. Johnson remembers his father telling him, “You need to take that to the backyard.”

“I didn’t know what I was. I didn’t know where I fit in. I didn’t know my place,” Johnson says of his childhood in Mesquite, a suburb that self-identifies as the Rodeo Capital of Texas. Johnson’s “place” turned out to be the Joy Sharp School of Dance, in north Mesquite. When he was nine, Johnson saw an ad in the newspaper for an all-boys jazz class that would cost $10 a month. Though money was tight, he knew he could get the tuition from either his maternal grandmother or his Uncle Bobby, an openly gay actor who always fostered his nephew’s artistic side (including getting young Justin a role as an extra in the local community college production of Brigadoon). Johnson was able to persuade his dad to let him go only because the son of a local baseball coach also happened to take jazz classes.

“He couldn’t take his eyes off of the queens onstage. They were so over-the-top, so campy.”

Joy Sharp, who had been running the studio for years, quickly took a shine to the small, freckled kid with all that energy and those emotive eyes. One day, when Johnson’s grandmother came to pick him up from class, Sharp took her aside and said Johnson had talent, creativity, and a strong work ethic, all attributes that would make him an excellent dancer. “He’s extraordinary,” Sharp said. Johnson, listening in, beamed. It was the first time in his life a coach had complimented him.

“Dance, I want to say, saved my life,” Johnson recalls. His teen years were not easy. He was conflicted about being gay, and he struggled with his parents’ eventual divorce. Teenage Johnson was grappling with big, complicated emotions, but he could channel them into dance. “It was just a place for me to communicate,” he says of Sharp’s studio, “and feel like I belonged somewhere.”

After high school, Johnson moved a couple hours west to attend Ranger College, a two-year school in Ranger, later transferring to the University of North Texas, in Denton. By then he’d been coaching junior drill teams and assistant teaching with some competitive dance squads, but he took a couple years off to focus on himself. He joined the UNT cheer squad, but it didn’t hold his attention for long. “I was born to be inside a studio in tights,” he says. “All of this out here in this heat, this Texas heat, on this football field, flipping and all, it’s not made for me.”

While he was in college, he came out as gay. “I discovered, you know, self-discovery,” he says. His mother said she’d known he was gay since he started to walk and talk. His father was less supportive, though he eventually came around. (In a moving episode of the behind-the-scenes series RuPaul’s Drag Race: Untucked!, he recorded a message of support from home for Edwards: “I know Dad was a hard-ass,” he said, “but I’m proud of you and who you are and what you’ve become.”) At UNT, Johnson made friends with other gay students, and sometimes they would all drive down to Dallas, to the blocks around the intersection of Cedar Springs Road and Oak Lawn Avenue, just north of downtown. That was considered Dallas’s “gayborhood.”

The streets in Oak Lawn, as the neighborhood is known, were filled with businesses that specifically catered to Dallas’s LGBT community. There was JR’s Bar & Grill, a gay club on Cedar Springs that opened in 1980, and the lesbian bar down the street from it, Sue Ellen’s, which opened in 1989. Across the road was the Round-Up Saloon, which touts itself as the “nation’s best gay country western dance hall,” and the clothing store Union Jack, owned and operated by a gay English expat since 1971. Johnson dined at an old-fashioned burger joint named Hunky’s. “I remember being so at a loss for words,” says Johnson. “And calling my mother saying, ‘Mom, do you know there is a whole community? A whole neighborhood?’ ”

A popular spot in Oak Lawn was the Village Station (now Station 4), which had a huge dance floor with a disco ball, where Johnson would stay until long after they set off the confetti cannons at midnight. It was there, in the upstairs Rose Room lounge, that Johnson stumbled onto his first drag show, an experience he likens to a “kid going to Disney for the first time.” He couldn’t take his eyes off of the queens onstage. They were so over-the-top, so campy. He stood at the back of the room, giggling. He noticed how people in the audience would show their appreciation for the entertainers by handing them crumpled dollar bills. He also noticed the smiles on everyone’s faces. “The atmosphere—the energy—was magnetic,” he recalls. “It just all made sense to me.”

By the time a twenty-year-old Johnson arrived at the Village Station, in 2000, Dallas already had one of the most established drag scenes in the state. The city’s drag history dates back to the fifties, when the cabaret Le Boeuf sur le Toit (later renamed Villa Fontana) opened in Bryan Place, about two and a half miles southeast of where Station 4 is now. According to a rigorous 2011 thesis on the rise of Dallas’s LGBT community, from Karen S. Wisely at UNT, Dallas was also home to Texas’s first gay bar, Club Reno, a downtown beer joint that opened in 1947. The city’s first organization for gay men, the Circle of Friends, was founded in 1965 and hosted Texas’s first known gay pride parade, in 1972.

The community that Johnson discovered in Oak Lawn was the product of decades of organization on the part of gay and lesbian Dallasites. In the seventies, gay bars and businesses started opening up along Cedar Springs Road, and organizations like the Dallas Gay Political Caucus fought for equitable treatment under the law through lobbying and litigation. Confronted with the AIDS epidemic of the eighties, the community became even more close-knit as it rallied to take care of its own. Drag performances were a crucial part of fundraising efforts.

In 1995 drag was popular enough in Dallas for the Dallas Morning News to publish a piece with the headline “Cross-dress for success: Drag-queen biz is booming—from performances to pageants.” Drag queens, said the article, were not just becoming more visible, they were becoming “big business.” The paper cited the Rose Room as an example. The dedicated drag venue, which had opened atop the Village Station in 1991, was routinely packed, attracting “straights and gays of varying ages” to the multiple hour-long performances it hosted every weekend night.

The Dallas area has sent more queens to Drag Race than any other city in Texas: Aside from Edwards, there’s Sahara Davenport, Kennedy Davenport, and A’Keria Chanel Davenport. There’s also Plastique Tiara, Asia O’Hara, and Shangela Laquifa Wadley, a.k.a. D. J. Pierce. Pierce started out as one of Edwards’s backup dancers when he was a student at SMU and now has his own HBO show, We’re Here. “I’ve always respected Texas drag,” Pierce says, “because it was so elegant and glamorous and it was big hair and jewelry and performance and being a showgirl who was competing in pageants. You know, it was just a beautiful thing and I really loved being a part of that world.”

Back in 2000 Johnson learned quickly. He started going to the Rose Room regularly, showing up early to get a good seat for performances by established drag queens like Whitney Paige, Maya Douglas, and Victoria West. One time he noticed a poster advertising amateur night, and he told his friends he was going to enter the competition. He didn’t really know anything about drag, but his experiences in competitive dance made him confident in his ability to entertain.

This was five years before YouTube was founded, so there were no online tutorials to teach Johnson how to contour, highlight, or paint the dramatic fake eyebrows that many drag queens apply. He took what little he had learned about makeup from his sisters and tried to make himself look as much like them as possible. He didn’t even buy a wig; he just slicked back his then platinum-blond hair like Annie Lennox. Before the show, the emcee asked what his drag name would be. Johnson picked “Alyssa,” because he’d watched Who’s the Boss? with his family growing up, and he thought Alyssa Milano had it all—the looks, the grace, and the sass that Johnson would want his drag self to exude. When he finally got onstage, Johnson channeled Milano in his performance. He danced his ass off. And he won.

It wasn’t long before Edwards’s talent attracted the attention of more experienced queens like Paige and Laken Edwards, the “drag mother” from whom Alyssa would get her last name. They mentored Edwards, and soon she was a top-tier pageant queen, winning Miss Gay Texas America in 2005, Miss Gay USofA in 2006, and then Miss Gay America in 2010, a title she had to relinquish when her commitment to Beyond Belief conflicted with the public appearances that came with the crown.

“His first love and life passion is the Beyond Belief dance studio. You can just tell whenever he talks about it.”

The “scandal” of Edwards’s ceded Miss Gay America title became a major plot point in season five of RuPaul’s Drag Race, on which Edwards competed against Coco Montrese, the former 2010 Miss Gay America runner-up who had taken over the “duties” Edwards had renounced. The played-up drama turned them into some of the franchise’s most memorable frenemies (who could forget the time when Edwards said, “Girl, look how orange you f—ing look,” about Coco’s makeup, or when Coco shouted, “I’m not joking, bitch!” at Edwards?). Their performances were so iconic that three years later both of them were brought back to compete against each other on season two of RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars, though by then their feud seemed to have fizzled. It was on All Stars’ second season—generally considered to be one of the greatest Drag Race seasons of all time—that Edwards cemented her status as a drag world idol. She was eliminated in episode seven, but her bigger, blonder looks and her humor—the intentional and the unintentional—made her a highlight of the season. One of her fellow competitors, Katya Zamolodchikova, called her “the most memorable creature to ever walk through that door.”

Beyond Belief shut down temporarily in March 2020 due to COVID-19 concerns, but Johnson couldn’t bear it. By June, the studio was back, for what Johnson referred to as a soft opening—no more than four or five kids in class at a time, with taped squares on the dance floor to keep students at least six feet apart.

Since Alyssa Edwards’s first season on Drag Race, in 2013, Johnson has remained devoted to Beyond Belief; if anything, he’s put even more thought and energy into what he can accomplish there. “In the last five years, he’s focused a lot on that,” says Robbins, who’s known Johnson since he was in his late twenties, driving a run-down Mazda with a smashed-in side that he couldn’t afford to fix. (He now drives a Mercedes.) “He’s really interested in the development of these kids—their maturity, self-discipline, and work ethic.”

He’s even brought the kids into the Alyssa Edwards world. They rode with Edwards on a float in Dallas’s 2019 Pride parade, and they performed with her onstage at RuPaul’s DragCon in 2016, in Los Angeles. Last year, when the makeup company Anastasia Beverly Hills released the limited-edition Alyssa Edwards palette (which features colors with names like Inspire and Texas Made), Johnson brought a group of Beyond Belief dancers for a flash mob at the Sephora at NorthPark Center. Each of the kids got their own palette and a makeup tutorial.

D. J. Pierce says he and Johnson have had the “why stay in Mesquite” conversation plenty of times since Alyssa Edwards became a household name. “If Justin wanted to explore opportunities in more television or film, then New York or L.A. definitely would be a place for him. But his first love and life passion is the Beyond Belief dance studio. You can just tell whenever he talks about it. He has a great passion for that school, to the point where he’s given a lot of his own personal money just to create scholarships for a lot of the dancers.”

That Thursday night in November, reclining cross-legged in one of the office’s black pleather armchairs, after Kirra and her mother left, Johnson looked totally at ease. It had been a productive practice, and, as usual, he’d had a blast.

“Have you ever met the real Hannah Montana? Because you’re looking at her,” he said. Johnson, like the Disney Channel heroine, leads a fabulous double life. He swept his arms in a circle. “It’s a blessing,” he said. In his mind, the studio was just as magical as any stage upon which Alyssa Edwards has planted her platform heels. The space was the opposite of the packed floor of DragCon, where Edwards’s fans wait in line for hours to meet their idol; the bland office park in which the studio sat was in stark contrast to the glittering Smirnoff-sponsored Pride parade float Edwards rode through New York City last June. The studio was silent now, but an industrious creative energy still hung in the air, and Johnson seemed to want to soak it up a while longer.

He knows he could start another elite dance studio on one of the coasts. But, he said, “this is home. I couldn’t live without this. I couldn’t create this in L.A. I’ve officially planted my roots and I’m here to stay. I want to be a part of this community. I want to be a bluebonnet that blooms all year round, that people are proud of.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Homecoming Queen.” Subscribe today.