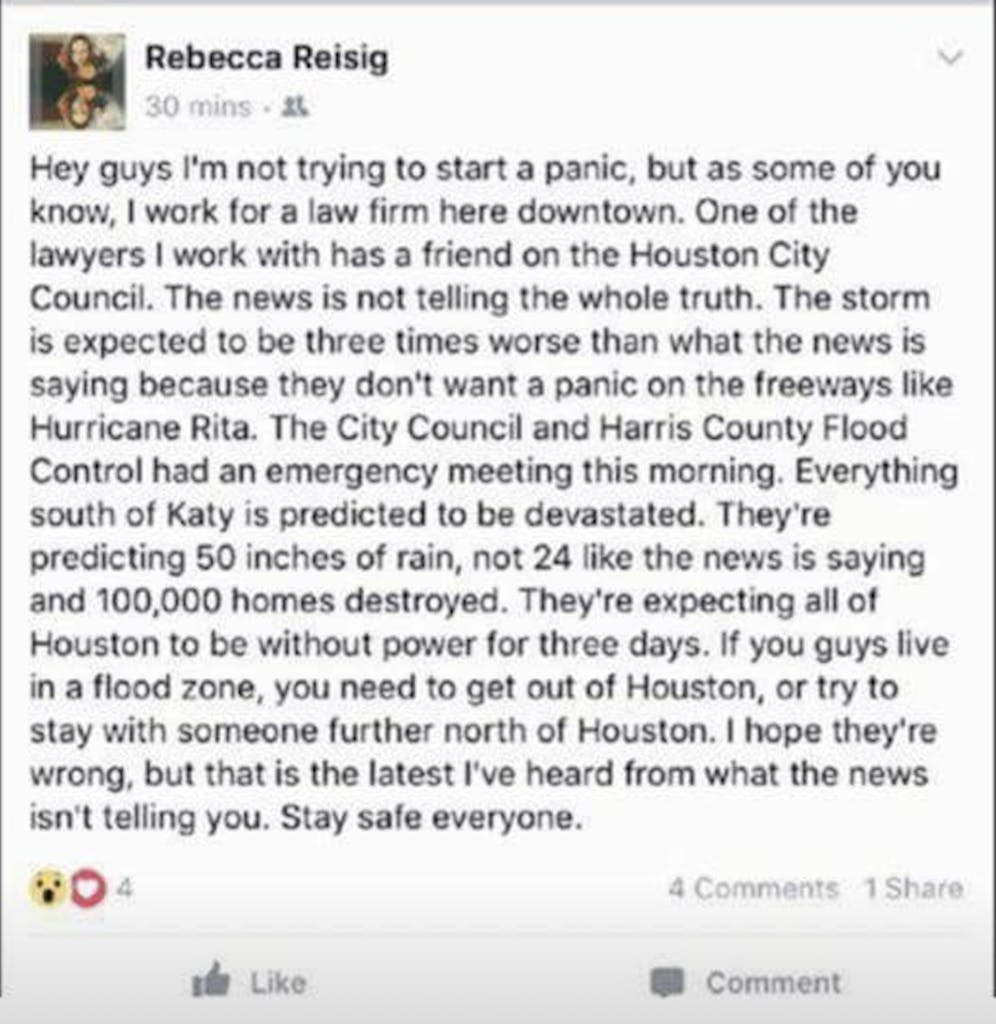

In the days leading up to Hurricane Harvey, Houstonians were forced to choose between contending forecasts. There was the official story: expect a severe rain event, perhaps one that could surpass the Memorial and Tax Day floods of recent years. Dangerous and awful, sure, but not downright biblical. Meanwhile, far more dire prognostications, purportedly based on information from inside government meetings, were circulating on social media.

The first message I saw from my living room sofa in Houston was from Rebecca Reisig.

There were other alarming messages circulating, too. One echoed Reisig’s post, adding that “every flood control district within Houston” attended the emergency meeting. (Untrue, as there is only one flood control district for all of Harris County, not multiple ones in Houston alone.) Authorities, the post added, “are worried the freeways would get clogged and people killed on freeways if they knew the extent of what’s about to happen,” warning that “FEMA and the National Guard are ready for a repeat of Katrina.”

The predictions in these posts were extreme, especially compared to the contemporaneous local forecasts of only 20 to 30 inches of rain. But they were eerily close to what happened next. The posts predicted 100,000 homes taking on water, and 10,000 of them submerged and ruined; according to the Houston Business Journal, those numbers came out post-Harvey at 99,803 and 15,725, respectively.

As the posts made the rounds online, Houston and Harris County officials were quick to debunk them. Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner’s office issued a press release on August 24 decrying “false forecasts and irresponsible rumors on social media.” Turner reiterated that he was not considering evacuation orders for Houston, adding that “rumors are nothing new, but the widespread use of social media has needlessly frightened many people today.”

Local media backed Turner up. KHOU categorically stated that tens of thousands of Houston homes would not be underwater. The Houston Chronicle reported that Harris County officials were “batting down false information making the rounds from a Sugar Land lawyer” named Ross Bale and “warning people not to fall for online hysteria.” (Meanwhile, Governor Greg Abbott contradicted Houston and Harris County officials, urging residents to strongly consider evacuating.)

According to the viral social media posts, the Houston City Council, the Army Corps of Engineers, and Harris County Commissioners were all withholding vital information from Houstonians. According to the politicians and the mainstream press, the online posts were alarmist nonsense. So was there a vast conspiracy to withhold the truth about the coming storm from Houston and Harris County? Did those meetings really take place?

Harris County Judge Ed Emmett flatly denies that meetings involving more severe storm predictions were held. “There was no meeting to talk about us hiding anything from the public,” Emmett says. Joe Stinebaker, a spokesman for Emmett, clarified in an email: “Absolutely no such meetings [as referred to in the viral posts] ever occurred. Aside from the ridiculousness of referring to ‘every flood control district in the city,’ there were no ’emergency meetings’ of [Harris County Flood Control District].”

Emmett defends his debunking of the social media rumors, even if they were more on the mark than the official forecasts Houston had been given. “There were people implying—not implying, but actually stating—that the government was not telling you the truth . . . That had to be put down early,” he says. “In an emergency you have to respond because if you don’t, it takes on a life of its own, and you have people out there doing dangerous things.”

Although some of the predictions in the viral posts—which all held similar information—were thankfully off the mark, the gargantuan rainfall totals and horrific property damage estimates were substantially correct. And one would hope that there would be emergency meetings of local officials if they were faced by such a disaster. But even if local officials are lying about those meetings and fibbing about knowing what was coming and when they knew it, was keeping the truth from their constituents the right call?

“When you ask if public officials would lie on order to protect the public, I think yeah, of course they would,” says Lance Porter, a professor of mass communications at LSU and an expert on disasters in the social media age. “And with good reason in this situation, but with social media, that lie won’t stay hidden. There are just too many ways for information to get out now.”

Indeed, even if Emmett knew that all those trillions of gallons of rain were heading Houston’s way, he says he would have made the same decision. “It’s the county judge’s job to call for the evacuation or not and frankly I didn’t for even more than 30 seconds consider evacuating,” he says. As Emmett explains, he would have had to request contraflow on major highways from the state, and answer to employers angry with forced closures due to uncertain weather patterns. “Even if we had known it was as massive as it was going to be, it was just not within the realm of possibility for us to evacuate.”

Mayor Turner, too, would have made the same call regardless of the forecast. Spokesman Alan Bernstein says that no matter how much rain was forecast to fall on Houston, no evacuation order would have been placed. “Yes, it would have been the same if you had 20, 30, 40, or 50 inches,” he says. “Houston learned some horrible lessons when we decided to evacuate from Rita in 2005, and it wasn’t the right decision.”

In flooding, Bernstein points out, you are far safer in your home than in your car. The worst of all possible scenarios for Houstonians in Harvey was a mass exodus on traffic-choked freeways. That fear of descent into chaos led millions of Houstonians to flee from Hurricane Rita, leading to dozens of deaths from heatstroke, bus fires, and accidents evacuating a storm that ultimately inflicted minimal to non-existent damage on Houston. After Harvey, which turned stretches of highway into lakes, hours of cars trapped on freeways would have been catastrophic.

That logic bears out in Harvey’s limited cost on human life. “Inside the Houston city limits, there were maybe a maximum of two people who were found dead from drowning in their homes,” Bernstein says. “But many, many more, including Steve Perez of the Houston Police Department, drowned in their cars.” Unlike during Rita, when a call to evacuate led to tragedy, this time the officials made the right call. Even if the government lied about the meetings, they were doing so to prevent the tragic deaths if millions of Houstonians had scrambled to evacuate all at once. Telling people to shelter in place was absolutely the right thing to do.