When Sterling Lands was growing up in Baton Rouge in the fifties, he’d often go hunting in the forests and flatlands near his home. Along with his dad, uncles, and cousins, he would head out in search of rabbits, squirrels, possums, geese, and turkeys—anything they could bring home for dinner. “We weren’t just hunting for sport,” he says. “We were looking for food.” But the lessons he learned on those trips transcended basic survival skills. “I could be a mile off, and they’d say, ‘Good shot. Next time, hold it like this,’ ” says Lands, now 74. “There’s a certain discipline that’s required.”

By the early nineties, Lands, who had moved to Austin and become the pastor of Greater Calvary Bible Church in 1984, realized hunting was an experience he wanted to share with the youngsters in his congregation. To make that happen, he worked with Andrew Sansom, then the director of Texas Parks and Wildlife. “All they know is a concrete jungle,” Lands told him. Sansom arranged a weekend excursion to Parrie Haynes Ranch, in Killeen, and Lands recruited several adults from the church—many of whom had never gone hunting themselves—to help him take a small group of kids from Greater Calvary on their inaugural hunting trip. Volunteers at the ranch taught them the basics of shooting, and two of the kids managed to kill deer. “I took both deer and had them made into sausage, and we fed the entire congregation,” says Lands. “It was a celebration for all of us.”

Lands believes the experience was transformative. “It broadened their perspectives,” he says. “Those kids have gone on to become teachers and engineers. One of them is a principal in Houston.”

Greater Calvary has since purchased its own fifty-acre tract of land an hour south of Austin, and hunting has become an integral part of its youth mentorship program, Rites of Passage. “You have to teach kids how to live responsibly,” says Lands. “If I can get a child to learn what it means to be character-centered, then they’re going to do the right thing, for the right reason.”

Considering the demographics of hunting today, the initiative is an outlier in many ways: the uncomfortable truth about the sport is that it’s too white, too old, and too steeped in antiquated traditions. “Hunting used to be a human thing,” explains Matt Dunfee, the director of special programs for the Wildlife Management Institute, who lives in Fort Collins, Colorado. “Now it’s become a middle-aged white guys thing.”

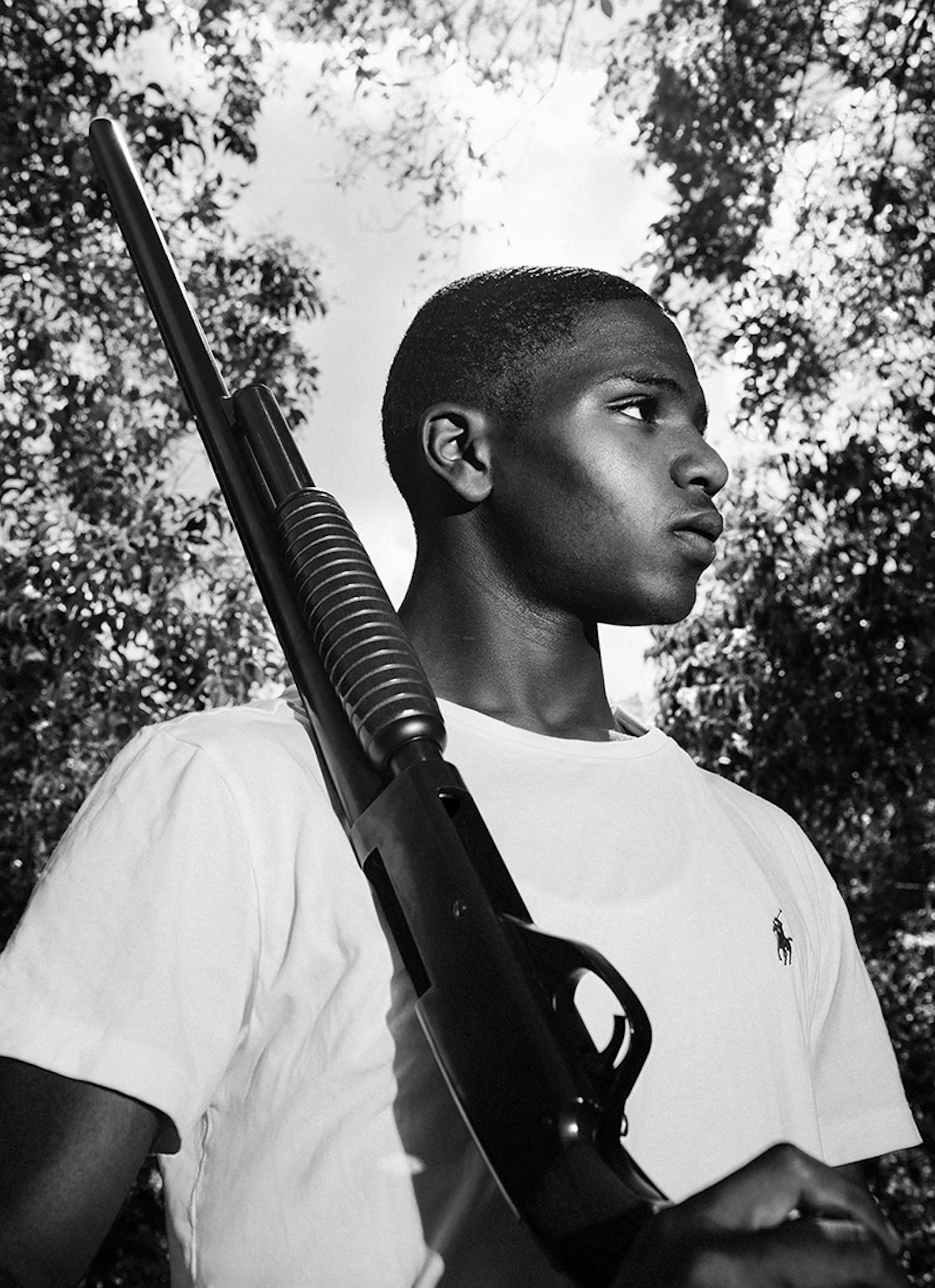

In conversations with several kids currently involved in the Greater Calvary program, we asked them to reflect on why they hunt and what the experience means to them.