When Ila Loetscher walked onto the set of the Late Show With David Letterman in 1985, the studio audience erupted in laughter. A petite woman in her eighties, her face wrinkled from decades spent in the sun, she held a live sea turtle that was dressed in a red dress and a tiny brown wig. Its flippers stuck straight out, unmoving, as if it were a puppet. Loetscher offered the reptile to Letterman.

“No, I don’t want it!” he said. As the laughter died down, Loetscher took a seat and began to tell Letterman about the turtle. “This is an Atlantic green, and its name is Gerry.” The rest of the segment went like a circus act crossed with a PBS special: Loetscher kissed the turtle. She had Gerry do tricks, such as stroking her face with its flippers. She shared facts about sea turtles and spoke about their endangered status. And, in a move that delighted the audience, she removed Gerry’s dress to reveal a pair of frilly pink bloomers.

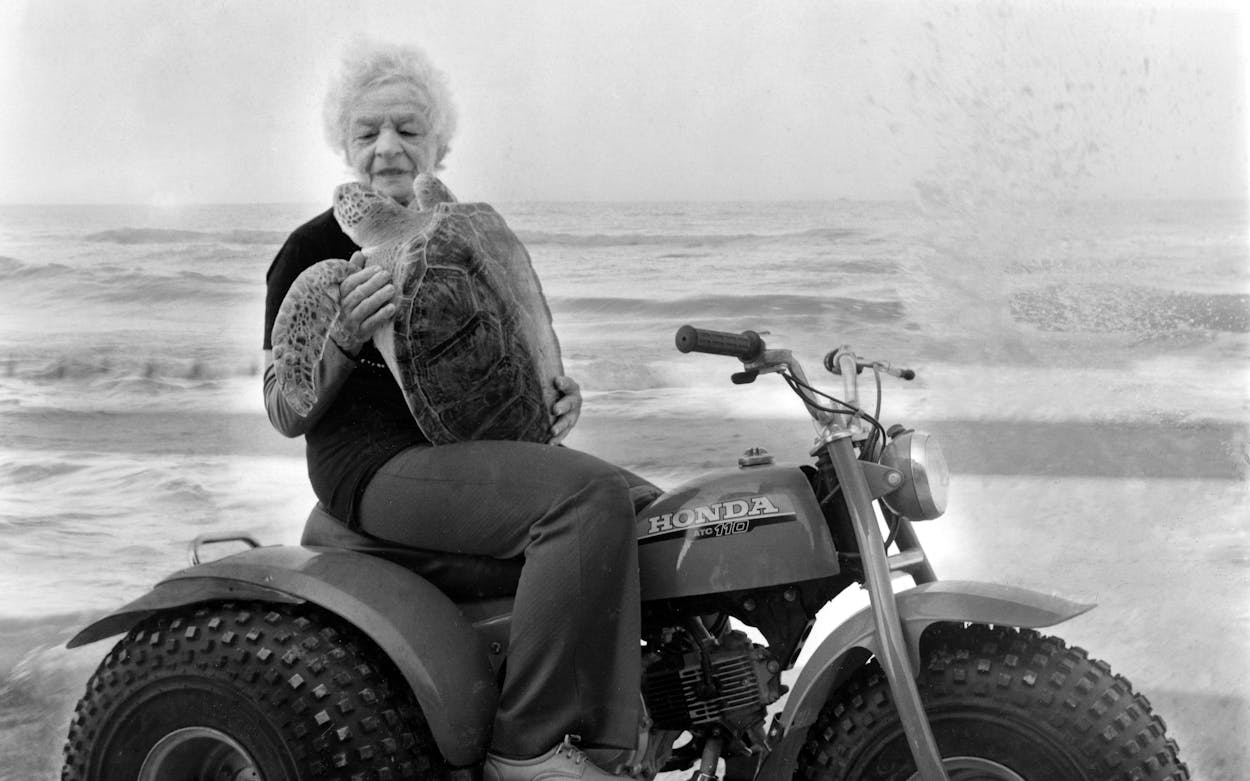

But Gerry was not just an exotic pet, and Loetscher not just a quirky sideshow act. After becoming one of the first female pilots in her home state of Iowa, she later moved to South Padre Island and in 1977 founded Sea Turtle Inc., a nonprofit that has rescued and released thousands of turtles. Known as the “Turtle Lady,” Loetscher was most famous for her educational presentations involving costumed sea turtles—a kitschy shtick that hasn’t aged well, but that nevertheless helped to educate thousands of people about endangered species. Her advocacy played a role in prompting stronger protections for sea turtles, including the Kemp’s ridley, which made a rare comeback from the brink of extinction. According to Sea Turtle Inc. board member Pat Burchfield, “She did more than all the turtle biologists and researchers put together to popularize sea turtles and the plight of sea turtles, and make that a worldwide phenomenon.”

Born October 30, 1904, Ila Fox exhibited a flair for showmanship early on. She grew up in Iowa, where she would put on plays with her siblings in the family’s barn. She studied drama and speech in college, and in her mid-twenties she enrolled in flying school, where she agreed to promote her school to the media in exchange for extra flying hours. “On Sundays and holidays it was my duty to adorn myself in the most sexy flying togs of that era (black riding boots, tight pants, white jacket, and a white helmet tucked under the arm),” she later wrote. “With the honest urge to succeed and a small serving of ‘ham’ thrown in, I soon learned to walk straight towards the newsman holding the biggest camera.” In 1929, Loetscher became the first Iowa woman to get a pilot’s license. She joined the Ninety-Nines, a women’s flying club founded by her friend Amelia Earhart.

After marrying her college sweetheart, David Loetscher, Ila quit flying and the couple moved to New Jersey. But the children she hoped for never came, and in 1955, David died of cancer. Loetscher’s parents had retired to Texas, and she decided to join them. After a stint in Pharr, she moved to Padre Island, where she befriended Dearl Adams, a citizen conservationist who wanted to establish a second nesting area for the endangered Kemp’s ridley. The species had only one rookery, in Mexico, and its numbers were plummeting as locals collected the eggs to sell as food (a practice that was legal at the time). From 1963 to 1967, Adams, his wife, and several friends gathered eggs from Mexico and planted them in the South Padre sand. Loetscher joined Adams on an egg-gathering trip in 1966. When 54 ridleys hatched that year, he gave her three, hoping she could raise them and learn more about the species.

“Those three hatchlings . . . were basically the genesis of the Sea Turtle Lady of South Padre Island,” says Burchfield, who also heads the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville. People who heard about Loetscher started bringing her injured sea turtles, and soon her beach house was filled with turtles splashing around in kiddie pools (she later installed tanks in the backyard). Loetscher obtained federal and state permits allowing her to care for the turtles, and eventually she released most of them into the wild. “They are such lovable and adorable creatures,” she told the Associated Press in 1977. “You just have to accept them as members of the family.”

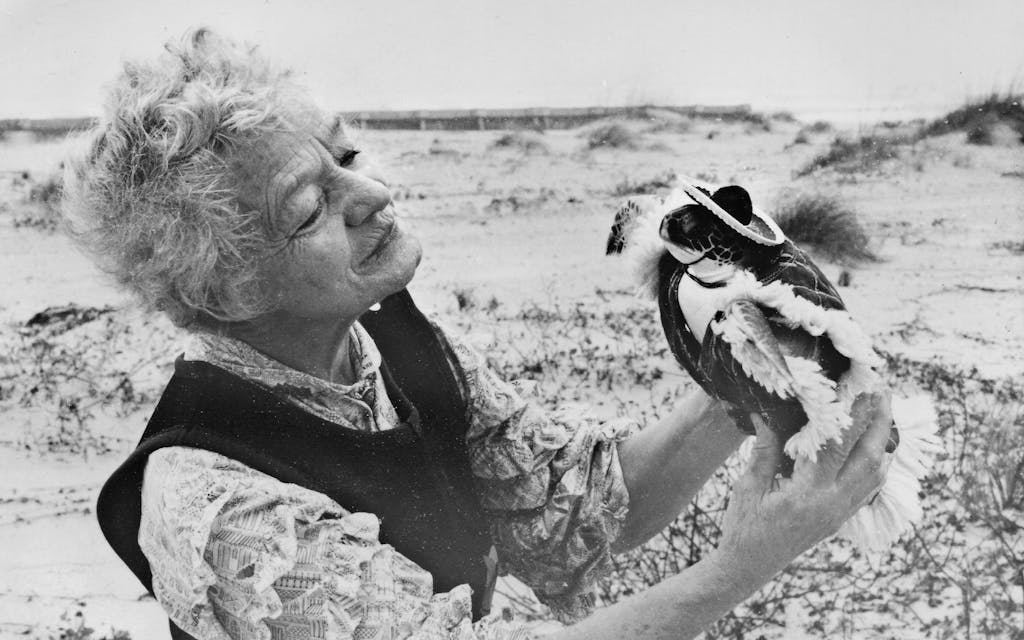

Recuperating turtles that were too big for the kiddie pools lived in submerged wooden enclosures in the bay. Curious locals and visitors began to stop by this spot, and Loetscher started giving “Meet the Turtles” talks there in the sixties. She publicized the turtles any way she could, holding annual birthday parties for them, bringing them to schools, and talking about them on local radio programs. Just as she had once advertised her flying school, she threw a serving of ham into her Turtle Lady persona. On multiple occasions, she even dressed turtles in pajamas and tucked them into miniature beds for the news cameras. (She had first recognized the entertainment value of costumed animals in New Jersey, where she once tickled community-theater audiences by bringing a costumed chicken onstage.) Loetscher also enlisted the help of a neighbor, who sewed an entire clothing collection for the reptiles. “She was always in the papers, and they had so much fun with her, ’cause she was so outgoing,” says her niece, Mary Ann Tous. “She was just a very dynamic person . . . If you met her, it was just—she engulfed you.”

The sombrero-wearing, suited, bewigged turtles helped rocket Loetscher to national fame. In addition to her Letterman appearance, she took two turtles on the The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in 1982. A Japanese TV show sent a crew to South Padre to profile her. Fan letters poured in from all over the country and from as far away as France. Tous remembers visits when she would wake up late at night and see the light shining on her aunt’s desk. “I’d say . . . ‘What are you doing?’ She says, ‘I’m answering the letters.’ I says, ‘But it’s so late, honey.’ She says, ‘Well, if they had the time to write, I have the time to answer.’ ”

Some observers disliked the turtle costumes. “I don’t think it caused any harm, but certainly a biologist would’ve looked askance at that,” says Burchfield. But, he says, “The ridley was almost gone entirely, and if they didn’t do something quickly, it would disappear forever. And despite all our best efforts as scientists, we weren’t making much headway, up until we started to get the general population behind that kind of a ground movement. . . . As soon as the public starts getting behind something, then the legislators and the people that can effect policy start to pay attention.”

Indeed, Loetscher’s efforts helped inspire stronger protections for the turtles. While only a few female ridleys returned to nest at Dearl Adams’s rookery, federal officials took notice of his and Loetscher’s work, and in 1978, Mexico and the U.S. initiated a multiagency project to restart the nesting area. The effort succeeded. The number of Kemp’s ridley nests in Texas rose exponentially until hitting 195 in 2008; it has gone up and down since, but maintains an annual average of 201.

Even after Loetscher died in 2000 at the age of 95, the changes kept coming. Oklahoma senator James Inhofe, who had once worked with her, became a key supporter of the 2004 Marine Turtle Conservation Act, which has provided millions of dollars for sea turtle conservation in other countries. In 2013, Texas made the Kemp’s ridley the state sea turtle. And Sea Turtle Inc., which grew out of Loetscher’s home clinic in 1977, has released nearly 50,000 hatchlings in the past ten years. It has also treated thousands of injured and impaired turtles, including a record number of cold-stunned turtles during the February 2021 freeze, and climate change will likely contribute to more such events. The organization also continues Loetscher’s educational work—687,000 visitors have dropped by in the past four years to tour the facility and see presentations, albeit without any costumed critters. Gerry, now 220 pounds, is still a star attraction.

In a society that sanctions cuddling puppies but not reptiles, Ila Loetscher was not afraid to wear her love for turtles on her sleeve. According to a 1977 article, she owned ceramic turtles, turtle-shaped jewelry, and turtle-themed ashtrays, paintings, and pot holders. She also believed her turtles could recognize her voice, obey commands, and even feel emotions. “I’ve learned a lot about love from my turtles,” Loetscher told a reporter in 1984. “I’ve learned human beings aren’t holding the whole secret.”

Once, a twelve-year-old boy was looking for a book about baseball when he came across Loetscher and her turtles at a library in Rockport. “I’m thinking, ‘This is just really strange. This is worth seeing what the heck this is,’ ” recalls Merritt Clifton. “I didn’t expect to be watching for very long, because I figured out it was a talk about sea turtles, and I didn’t know beans about sea turtles. I didn’t care beans about sea turtles.” Loetscher made such an impression on him that he stayed for the whole presentation. He later grew up to become an environmental journalist, and he now runs a site about animal news. “The whole concept of ecology—as everything relating to everything else—she was the first one that I heard it from,” says Clifton, now 68. “That talk was where I first heard about an outlook that would influence me for the rest of my life.”

For Loetscher, a widow with no children of her own, her turtles and the people at her presentations formed a sort of family. “When the school buses would come [to Sea Turtle Inc.], full of children, she would wait outside the door with a little turtle in her hand,” says Tous. “And the turtle would be, you know, waving its little flipper. . . . The children would unload and walk by her, and they’d look at her with so much love.”

Clifton wasn’t the only kid who was inspired by a presentation from the Turtle Lady. “Some of them grew up to be biologists who are now working with the turtles,” says Donna Shaver, who knew Loetscher and leads turtle conservation at Padre Island National Seashore. Others, she says, “became wealthy developers and they gave contributions that helped start rehab hospitals, or do other things for sea turtles. You need all of society to be supportive in various ways.”

“There’s that saying that you can’t conserve what you don’t love, and you can’t love what you don’t see,” Shaver adds. “She gave [people] the opportunity to see these animals.”

- More About:

- Critters

- South Texas

- South Padre Island