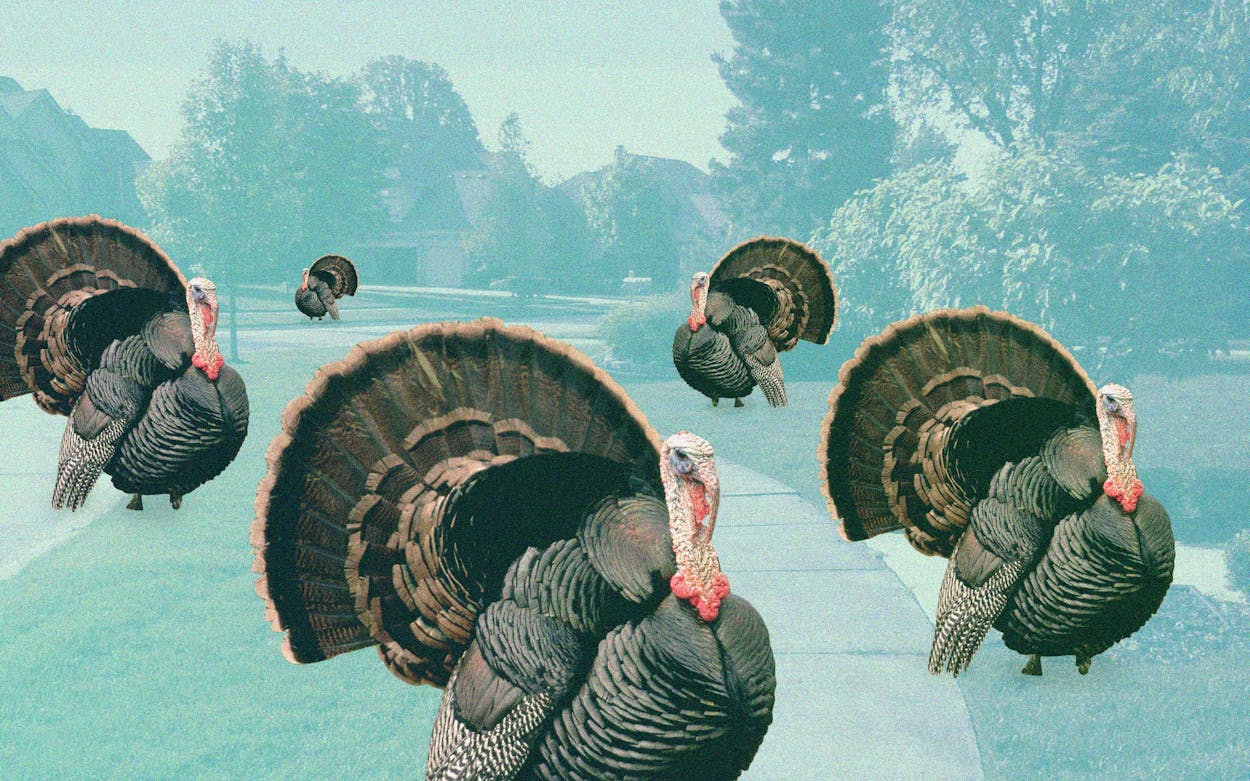

For as long as anyone can remember, the flock of wild Rio Grande turkeys that live in Sun City, a sprawling 55-and-over community in Georgetown, had coexisted peacefully with the retirees. The turkeys mostly stayed in the greenways and wooded areas around Berry Creek, while the humans stayed in their homes and on the golf courses. The two groups met only on the hiking trails, where the humans might marvel at the turkeys’ iridescent feathers, long red wattles, and funky head-bobbing struts before the birds would trot away in a flurry of tail feathers.

Or maybe the turkeys were just lulling the seniors into a false sense of security. Last summer a few young male gobblers left the greenways and took to promenading in pairs through the streets of Sun City. If they saw a car, bicycle, or golf cart coming, they would stand in the middle of the road until the vehicle stopped, whereupon they would rush forward and start pecking at the tires. Eventually they would make their way to the driver’s side, and when the car began to pull away, they would give chase. Sometimes the animals would block driveways or stand behind parked cars while residents tried to fend them off with brooms or decorative pillows hastily seized from porch furniture.

It was funny at first. Residents began referring to the turkeys as “the renegades.” They told stories over dinners and mah-jongg games about their broom-wielding exploits. But then things took a turn.

One day in January, on her morning walk, Joan Altshuler, 78, had a frightening encounter with the renegades. “I was walking on a street I don’t normally walk on,” she remembers, “and the wild turkeys came up behind me and rammed into me, right in the kidney area. Not once, but twice.” The two turkeys were each more than three feet tall—they came up to Altshuler’s chest—and though a grown gobbler weighs only about twenty pounds, they hit her with so much force, she was sure they outweighed her. “Luckily, I didn’t fall. If I fell, I wouldn’t have been able to get up and I would have been in bigger trouble. I could see every pimple on their faces, that’s how close they were.”

Altshuler ran to a nearby porch for refuge. Unfortunately no one was home. The turkeys followed and stood at the foot of the stairs. She was stuck. “The turkeys barricaded me,” she says. “They wouldn’t let me get down. Then they got bored and started going off in another direction. I started slinking around the side of the house, and I started throwing rocks from the garden.”

Once Altshuler was free, she went home and called a friend who was on the Sun City community association’s wildlife committee. With the aid of Warren Bluntzer, a wildlife biologist and consultant, the committee launched an investigation.

It was generally agreed, though no one has any definitive proof, that the change in turkey behavior had occurred because someone had been feeding them. Once wild animals become habituated to human contact, Bluntzer explains, they can lose their fear of humans and become territorial and aggressive.

The Sun City community association swiftly enacted a rule forbidding people to feed turkeys. They also advised residents to “haze” the birds by shouting, blowing horns or whistles, or bringing dogs with them on walks. (Altshuler suspects the turkeys attacked her when they did because it was the first time she’d gone out without her dog, Jett, a Lhasa apso mix who had died the day before.) Walking is a favorite form of exercise in Sun City, and many residents took to arming themselves with sticks or nine irons.

The gobblers were undeterred. The attacks continued, mostly on smaller, older women, and they grew more serious. The turkeys began going after delivery drivers and postal carriers. One woman had to go to the emergency room for a tetanus shot after the turkeys scratched her with their talons. Another was pecked when she went out to get her mail, and two months later, she was still afraid to go out in her own yard.

“People say it’s no problem to stand up to them and it’s all fine and dandy,” says Barb Meese, a neighborhood representative in the community association, “but when you’re eighty-seven years old and there’s a turkey hiding behind a bush and it startles you, well, you’re not as sure-footed as you were in your twenties. . . . I think that’s what’s going to happen someday: a little old lady is going to get startled and lose her footing and crack her head.”

The community decided that the gobblers had moved from nuisance to hazard, and since hazing wasn’t working, it was time for more drastic measures. But wild turkeys are officially classified as game birds, regulated and protected by the state, so neither the community nor Bluntzer can take action without authorization from Texas Parks and Wildlife.

While Rio Grande turkeys roam throughout much of the state, no one at TPWD had ever heard of them acting aggressively toward humans, at least not in Texas, says Derrick Wolter, TPWD’s senior wildlife biologist for the Hill Country. The department’s turkey specialist had to consult with experts in Rhode Island and South Carolina. In the end, the community association of Sun City was presented with two options: relocation or depredation, a fancy scientific term for killing, most likely with a gun. (It’s most frequently used when animals destroy crops or when they pose public safety issues, such as by refusing to get off airport runways.)

Each option has its own set of problems, says Bluntzer. Both require permits from TPWD, and to get those, certain criteria have to be met. A depredation permit would also only be valid on property owned by the community association, but the majority of the land in Sun City is privately owned. Then there’s the problem of correctly identifying the renegades. It’s possible that multiple pairs of young males have taken to roaming the streets, and it’s unclear which have been the perpetrators of the attacks.

Finally, if the miscreants are successfully captured and relocated (most likely after being stunned with a tranquilizer gun), the biologists will have to make sure they meet certain criteria—for example, that they won’t be bringing diseases with them to their new home and that they’ll be able to coexist with the wildlife that already live there. And their behavior won’t change: they’re already habituated to humans.

Depredation, in some ways, would be simpler. “It would bring closure to the situation,” says Wolter. “It seems like the right thing to do.” It would also not be harming an endangered species. “There’s no shortage of Rio Grande turkeys,” he continues. “There are about six hundred thousand in the western two-thirds of the state. As a species, they’re doing quite well.” They also, he notes, make for decent eating.

The community association of Sun City is still considering its next move. Right now, it’s still hoping to trap the turkeys and remove them to a nearby ranch, but that could change, depending on whether the birds continue to attack residents or elude their captors.

But even if—or when—the immediate problem of these particular turkeys is solved, the larger problem of human-wildlife relations remains. Both Bluntzer and Wolter worry that as Texans continue to expand into territory previously inhabited only by animals, the conflicts will continue, especially if humans ignore warnings from wildlife experts and try to feed animals. That only leads to a breakdown in the separation between the human and animal worlds, and that’s how you get bears shoplifting in convenience stores and wild turkeys attacking old ladies.

“We’re only on the cusp of wildlife conflict with humans,” Bluntzer warns. “Population numbers are swelling everywhere. The next thing is how you manage them. But will that work and be successful? No one knows what the future will hold, but the problem’s not going to go away.”

- More About:

- Critters

- Georgetown