This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The Texans on these pages are a diverse group. Some are professional soldiers; others were drafted into combat and returned to civilian life. Some have advanced academic degrees; others never finished high school. Some are bitter about their war experience; others are proud. Some specialized in killing the enemy; others specialized in tending to the wounded.

They are among the few winners of the Medal of Honor, our nation’s highest military award. It requires “gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.” If any of these men had stopped halfway through battle and requested medical attention for their wounds or let someone else knock out the last enemy bunker, they might still have been decorated for their bravery, but they would not have earned the Medal of Honor. None stopped halfway. They won the medal and lived to tell about it—no small accomplishment. When the medal is given, more times than not it is given posthumously. More than half of the 65 Texas holders of the Medal of Honor since 1863 were not alive to receive it. Today there are 17 living Medal of Honor winners in Texas.

Despite White House ceremonies, despite being enshrined in the Hall of Heroes at the Pentagon, none of the medal winners feel like heroes. Instead, they feel lucky or obligated to the men who did not survive or simply satisfied that they did the job they were trained to do and did it well. Yet they acknowledge that on one day, at least, it has been recorded and witnessed that they were leaders of men and fearless. On one day they were heroes.

They are still treated like heroes and enjoy numerous benefits, reflections of the esteem in which they are held. Each receives a pension of $200 a month for life. The Veterans Administration is under presidential order to hire all medal winners who seek employment. Free passage, on a space-available basis, is guaranteed on government airplanes. Their children can receive appointments to the military academies without competing within the usual quotas. Texas offers a free red-white-and-blue license plate bearing the words “Congressional Medal of Honor.”

Those who agreed to be interviewed spoke mostly in factual terms about their exploits, careful not to exaggerate. Some say they remember very little. Others remember everything but make only a passing reference to their moment of invincibility.

David Kramer is a writer who lives in Austin.

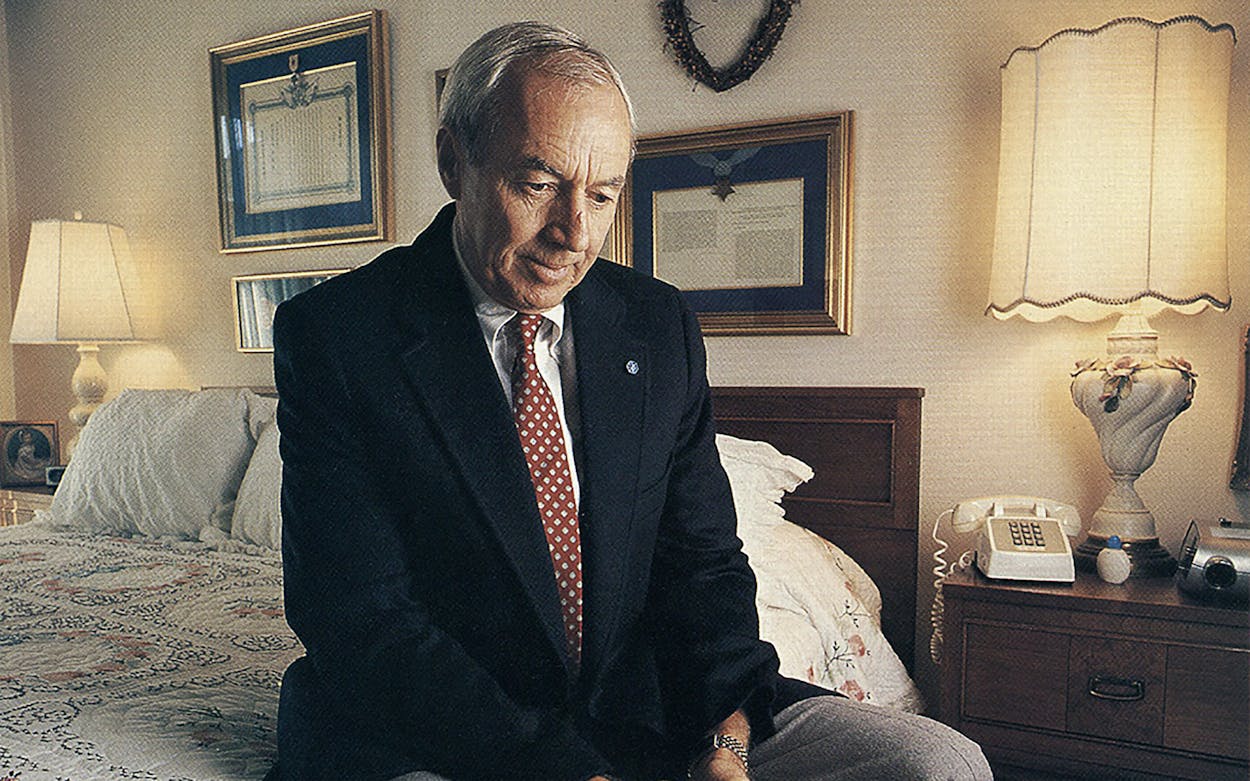

George H. O’Brien, Jr.

Midland • Geologist

It was an October morning in Korea, about two or three o’clock, and I was chilly. I was a second lieutenant in charge of a rifle platoon that was in reserve behind the front lines. I got in line for a hot cup of coffee. It turned out that I was in a line where they were handing out grenades. We were soon loaded into trucks, driven to the front, and put in an assault position against a North Korean and Chinese force. The fighting was intense; I engaged three of the enemy in hand-to-hand combat. I was shot through the arm and struck down by the concussion of grenades three times, but I refused medical treatment. We started out with about sixty men, and ended up with seven. • My troops—the survivors—who were all Marines, wrote the letter recommending that I get the medal. It was quite an effort for many of them who couldn’t write very well to put the whole story down on paper. There were no forms they could use, and no officer assisted them. • When I came home to Big Spring there was a parade in my honor. It was very moving to see that the people in my hometown cared that much.

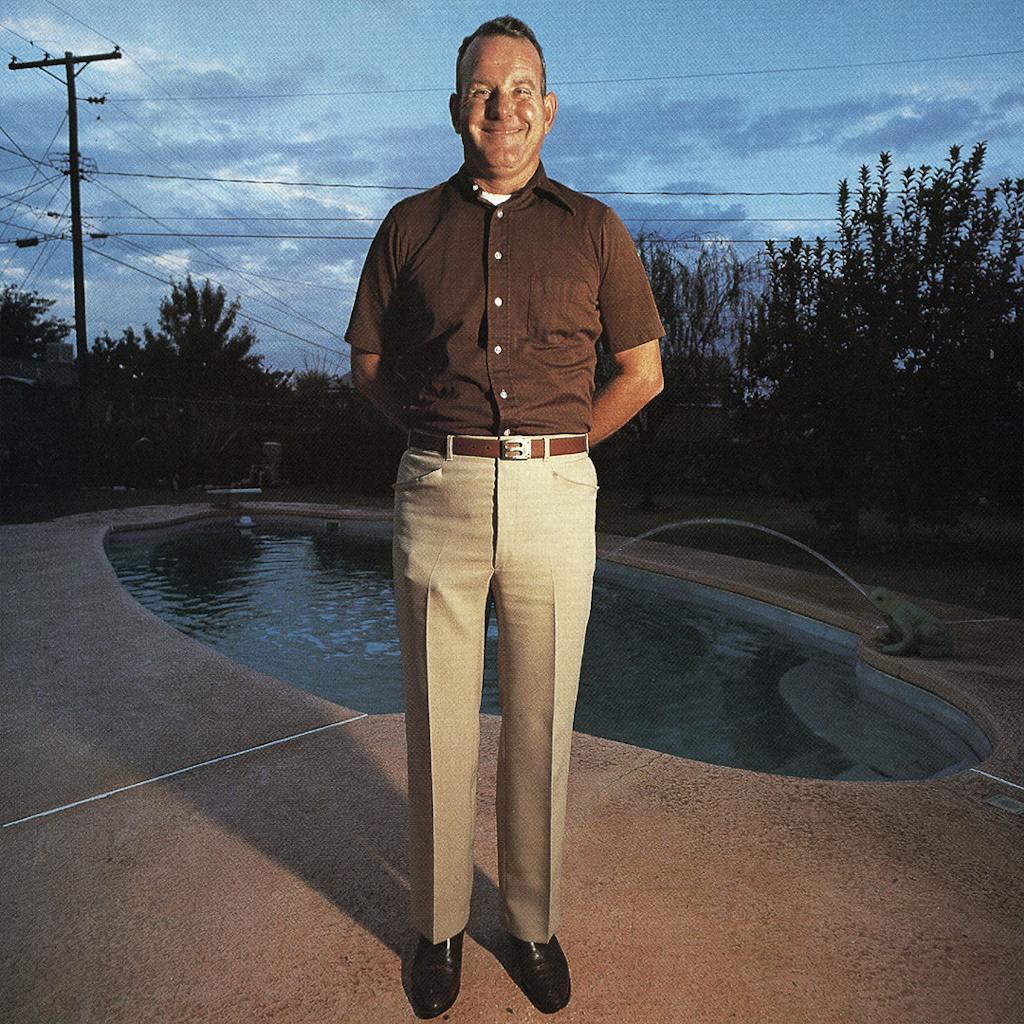

James M. Logan

Kilgore • Retired Oil-Field Worker

I was a sergeant, a rifleman, and I landed with the first wave of the assault on the Gulf of Salerno beaches on September 9, 1943. We had advanced eight hundred yards to the forward bank of an irrigation canal when the enemy began a counterattack from a rock wall two hundred yards farther inland. It was a bit rough. I had to get off that damn flat ground we were on. So I jumped up and ran toward the wall. It seemed like a good thing to do, though I was the only one to do it. • I was surprised to still be alive when I reached the wall. Everything was there for me; I didn’t have to figure anything out. I crawled along the base until I reached the machine gun. I shot the two gunners and turned the machine gun against the Germans. They all ran away. Later that morning I went after a sniper hidden in a house. I ran through one hundred fifty yards of enemy fire and kicked the door in just as the sniper reached the bottom of the stairs. I shot him. • I do not feel like a hero. I’m proud, but I try to live as quietly as I can. I’ve worked all my life in the oil fields, but I can’t work anymore, so I just get by.

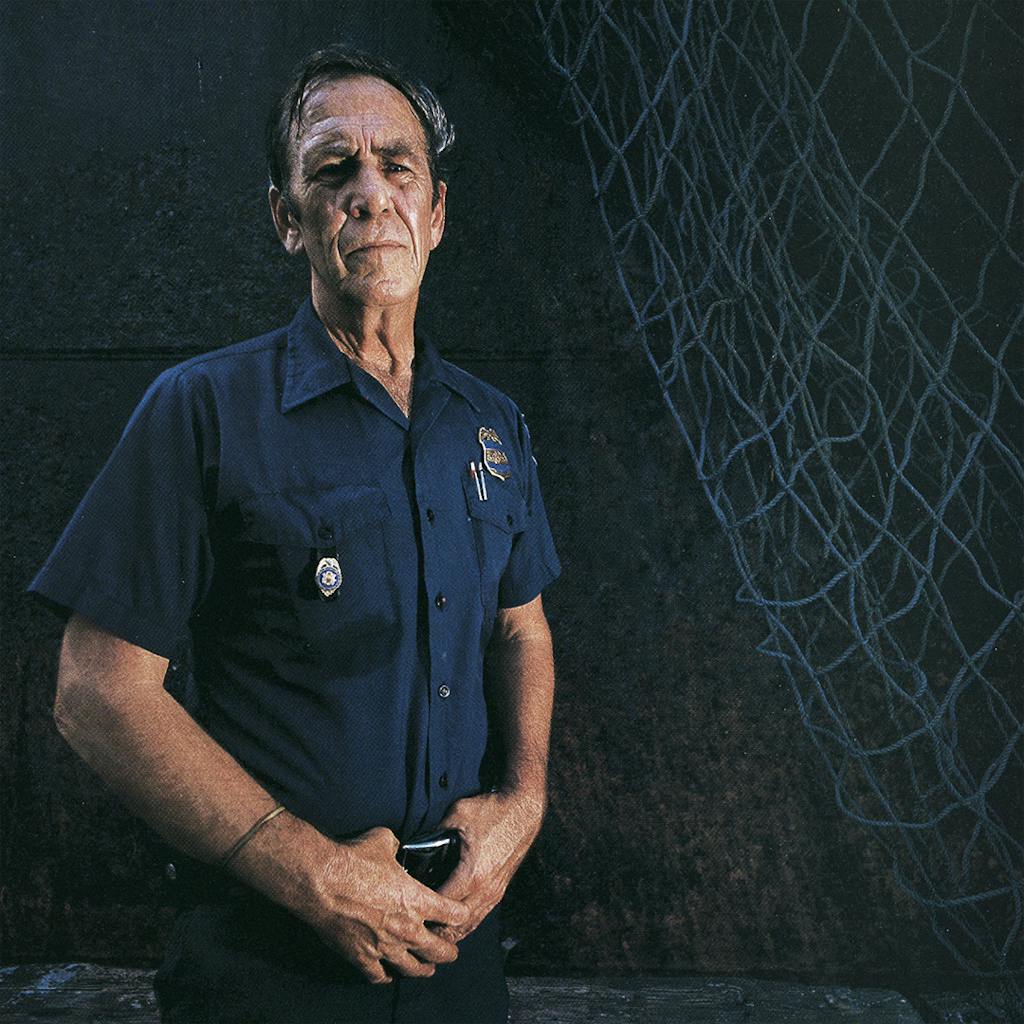

Robert M. Patterson

El Paso • Career Military

There are five hours in my life that I have no memory of, and during those five hours I earned the Medal of Honor. I remember starting a sweep of a Vietnamese village on the morning of May 6, 1968. About halfway through the village, we stopped for lunch. As we started to move again, we got hit, and the next thing I knew it was five o’clock that evening and I was in a five-hundred-pound-bomb crater. • According to the men in my unit who proposed that I receive the medal, our platoon was pinned down by heavy automatic-weapon and grenade fire from a tight network of one- and two-man spider holes. Though others warned me not to go on, I got up to assault the enemy position. With rifle and grenade fire, I killed eight enemy soldiers in five spider holes and captured seven weapons. I took grenade shrapnel in the legs. • When I was told that I had been nominated for the Medal of Honor, I thought it was a practical joke. I didn’t know of anything I had done to deserve it. If somebody else had been in the same situation, they would have done the same thing. It just happened to be my turn.

David H. McNerney

Crosby • Retired Military

I was a professional soldier. I had been in active combat in Vietnam for about three years before the day I earned the Medal of Honor, March 22, 1967. • My company, about eighty-five of us, ran into a North Vietnamese battalion that hit the front of the column real hard, ambushed the platoon at the rear, and surrounded us. The commander and the artillery forward observer were killed early on, so as first sergeant, I had to take over. We held on as best we could. There was no way out until B Company could move up to assist us. • We tried all day long to break through. I had to blow up some big trees so that a helicopter could land, and even then it was tricky. By the time B Company came in just at dark, we had twenty-two dead and about forty wounded. My chest had been lacerated by a grenade, but unless you’re really hurt bad, your adrenaline keeps you going. • I didn’t give a damn about what the war was about. I was a professional soldier. That was my job. That was the whole thing. That’s why I did what I did. It wasn’t a normal day. I was fighting for my life.

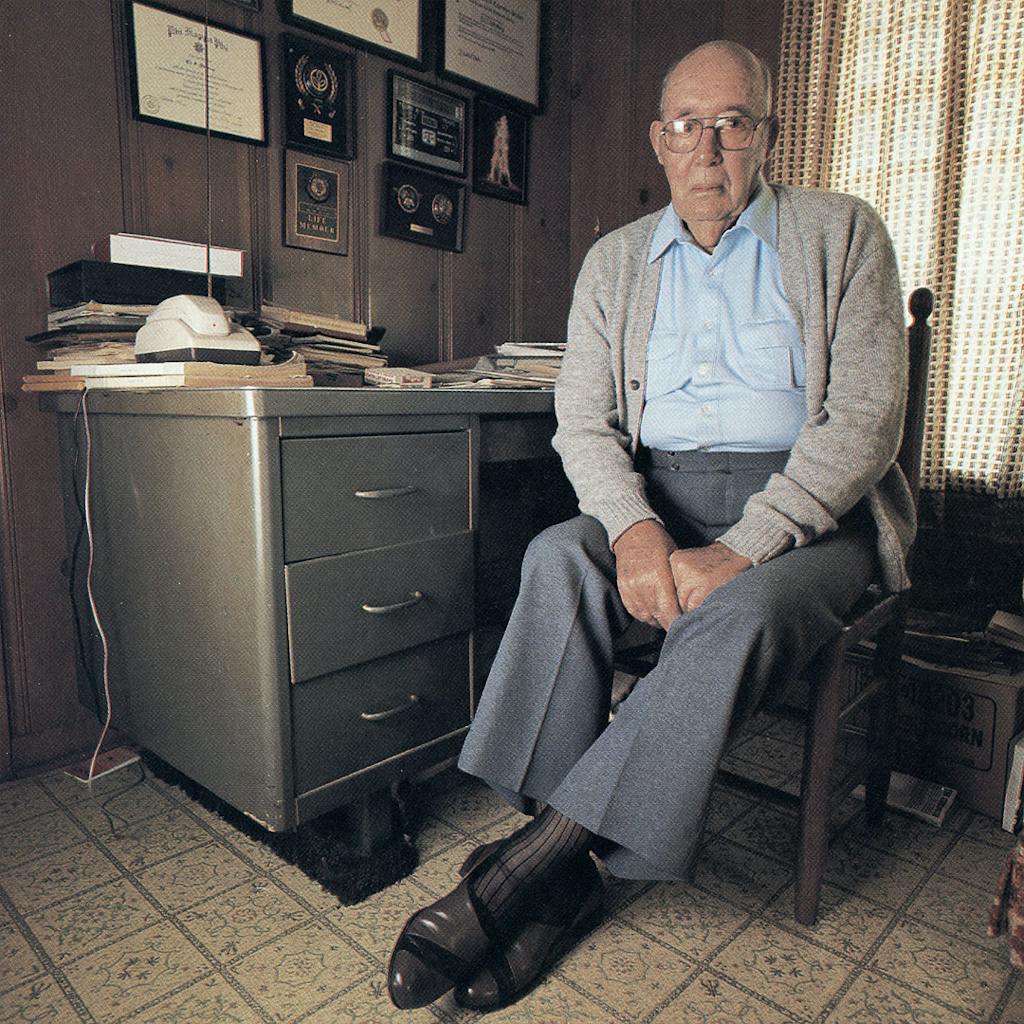

Eli Whiteley

College Station • Retired Agronomy Professor

They told us we could stay in Strasbourg until after Christmas. But the Battle of the Bulge began, and we moved out on December 19, 1944. I was a first lieutenant in L Company, which had one hundred and twenty-five men. We reached the outskirts of Sigolsheim on Christmas Eve with twenty-six men left. Sigolsheim had about fifty houses, with four to twelve Germans hiding in each. And of course they had machine guns and automatic weapons set up. • President Truman gave me the medal. I felt a sense of pride in a job that maybe was well done, and I felt somewhat awed at being one of the select few. There were about sixteen million people involved in World War II, and only around four hundred received the medal. In each case, whatever that individual had within him came out at that point when the medal was earned. I don’t know whether you call it courage or anger or whatever, but it fires you to go ahead and do that job. A very good friend fell on a grenade to cover it. He made that sacrifice to protect his men. It’s one of those things that happens. One of those things you just do.

Clarence E. Sasser

Rosharon • Veterans Administrator

I was a combat medic with a company in excess of a hundred men dropped by a helicopter into a small rice paddy about a hundred meters from the wood line. We realized instantly that we had stumbled into a well-fortified Vietcong base camp. In the first few minutes there were thirty casualties. Less than twenty guys escaped without a scratch. I had a gunshot wound through the leg and several additional wounds. But if you could still move, you were lucky, really lucky. • With my legs swollen and bleeding, I grabbed bunches of rice to pull myself along, sliding on top of the mud. People were begging for help, and I was out of supplies. I gave them what comfort I could until the enemy withdrew just before daybreak. It was one bad day and the worst night I ever spent. • All the members of my family were flown to Washington, D.C., when I received the medal. It was one of the major things in our lives. The medal changes your life tremendously. It brings recognition, but it is also a cross to bear. It forces a person to live up to other people’s standards. I enjoy it, but it does become a responsibility.

Roy P. Benavidez

El Campo • Retired Military

On May 2, 1968, a twelve-man Special Forces reconnaissance team ran into heavy Vietcong resistance on the ground and requested emergency extraction. Three helicopters tried to get through, but the enemy’s fire was too intense. When I found out that the team leader was a soldier who had risked his life to save mine, I made the sign of the cross and jumped into the fourth helicopter. • According to the citation, I dragged and carried the wounded team members into the helicopter and went to the body of the dead team leader to remove classified documents. Then the pilot of the helicopter was killed, and the helicopter crashed to the ground. A fifth helicopter came in, and I loaded up the wounded again. I was clubbed from behind by an enemy soldier. I killed him in hand-to-hand combat. I also killed two other enemy soldiers who were rushing the helicopter. I climbed in and passed out. I was wounded in the right leg, face, head, abdomen, and thigh from small-arms fire, in the back from grenade fragments, and in the head and arms from hand-to-hand combat. I’m called a walking road map.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Military