In the course of the federal grand jury hearing on Randy Webster’s death, one member of the panel asked Officer Wayne Holloway if he had ever heard the slang term “throwdown.” Holloway said he had. “Would you describe to us what your interpretation of a throwdown would be?” the juror asked.

“Just a planted weapon,” he replied. “Okay,” said the juror.

“It don’t have to be a weapon,” Holloway added. “Any kind of plant, like drugs or something like that. It doesn’t have to be a weapon.”

Another juror spoke up. “Have you ever witnessed any such act as that since you have been on the police department?” “No, ma’am,” said Holloway.

The Boy

Randy Webster was an engaging, spirited, not particularly disciplined kid. At seventeen he was six-foot-two, with longish, neatly combed blond hair. He got into trouble now and again, but people liked him—he was friendly, funny, and a bit of a show-off, eager to let the world know that he didn’t take himself or life too seriously. He was, as the father of one of his girlfriends remembers, “a superfine kid—if I had a boy, I’d want him to be just like Randy.”

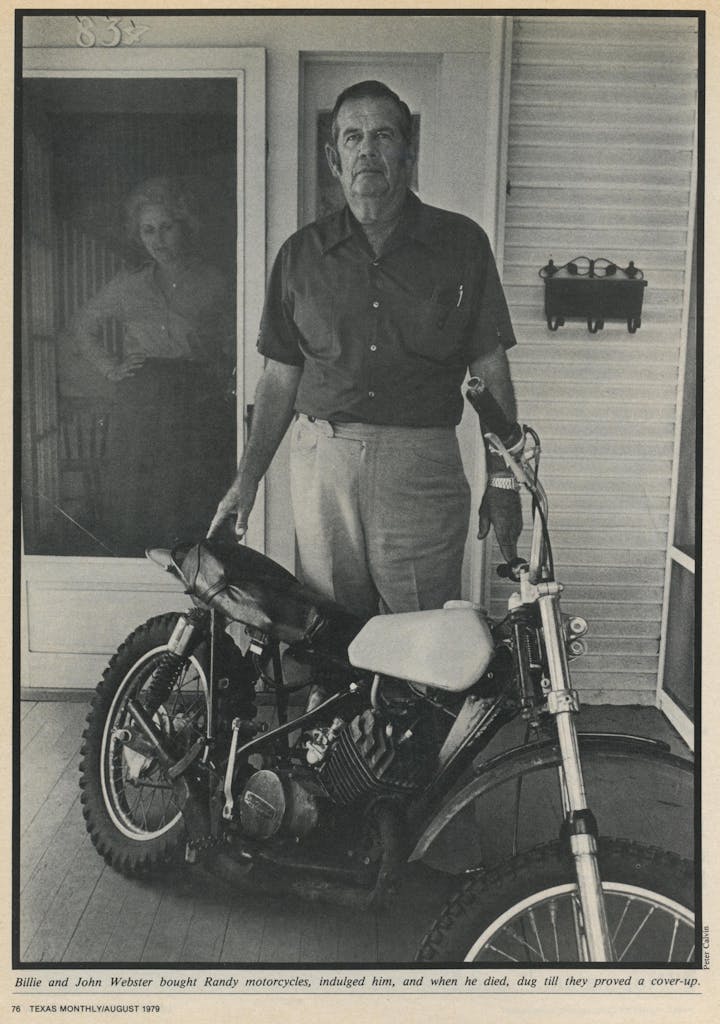

Like many youngest children—his older brothers were twelve and seventeen when he was born—Randy was indulged by his parents. “They let me do most of the things that I want,” he wrote in an essay for school when he was thirteen, “and buy me a lot of things, also. Sometimes I think that they are too strict, but usually they are all right.” By the time he was fifteen they had bought him three motorcycles, starting with a bright yellow Mini Trail 50 dirt bike when he was eleven. There were open fields on the outskirts of Shreveport, Louisiana, where the Websters lived, and often after school he would ride there until dusk. His ambition, he wrote in that school essay, was to be “a great and famous racer,” to win the world championship motocross race.

Until 1972 Randy’s father, John Webster, ran a building contracting business that was prosperous enough to allow him to build his family a $70,000 brick house in a pleasant, middle-class Shreveport subdivision called Southern Hills. But the recession wiped out the business, and John Webster had to start a new career—operating a bass-fishing camp for American tourists on a manmade lake in central Mexico. He commuted between Shreveport and the fishing camp in a small private airplane, running two fishing parties most weeks and often only making it home on Sundays. So after he was thirteen, Randy was raised mostly by his mother, Billie, a handsome, intelligent woman who had been a full-time wife and mother since her marriage at fifteen.

“Every single thing that I do now seems a little bit harder since I became a teenager,” Randy wrote when he was thirteen. His teenage years weren’t easy for his mother, either. He was the first of her three children to talk back to her at all, and he resisted all attempts to make him attend to his schoolwork. “We really had some battles royal over that,” says Billie Webster. “I wasn’t enough of a disciplinarian. I didn’t give him enough responsibility.”

Randy began to have minor scrapes with the law. Once he got caught stealing hubcaps. Another time, he hot-wired and stole a motorcycle, and the police caught him at that, too. He was a show-off and a hellion, but not really a bad kid. “Sure, we saw him a few times,” says a sergeant in the juvenile division of the Shreveport Police Department, “but he wasn’t what you’d call a hardened criminal.”

Randy started his high school education at Southwood High, but after he was suspended three times for having long hair and for smoking in school, he was transferred to an alternative public high school for difficult kids called School Away From School. For a time he seemed to be responding to the looser rules and self-paced atmosphere of School Away, and at his mother’s urging he began seeing a therapist at Shreveport’s Family Counseling and Children’s Service. But after a year or so he was skipping school regularly and hanging around with what his family and old friends regarded as a bad crowd. His father gave him a Ford Pinto on condition that he stay in school and improve his grades, and when the car was totaled in a wreck John Webster refused to replace it, saying Randy hadn’t held up his part of the bargain. Relations between father and son deteriorated, and in the fall of 1976 Randy dropped out of school.

After Christmas Randy told his parents he was going to enlist in the Navy with a friend and while in the service would work toward passing a high school equivalency exam. His mother was hopeful, his father dubious, but they both signed papers permitting him to join the Navy while he was still seventeen. His enlistment was set for Monday, February 7, 1977.

On Saturday night, February 5, Randy was in extremely good spirits. He dressed carefully in Southern Saturday Night Fever style—blow-dry hair, jeans, denim jacket, boots—and told his mother, while he was preening in front of the mirror, how good-looking he was. He said he was going to spend the night at a friend’s house, gave her the phone number where he could be reached, borrowed her car keys, and kissed her goodbye.

He didn’t come home or call on Sunday. John Webster arrived from Mexico that day, and he told his wife not to worry. If Randy had wrecked her car and was ashamed to own up to it, Webster would buy her a new one.

There was still no word from Randy on Monday.

Sometime before dawn on Tuesday, a phone call awakened the Websters. Billie Webster picked up the extension next to her bed.

“This is the medical examiner’s office in Houston,” a man’s voice on the other end of the line said. She recoiled involuntarily and dropped the receiver on the bed. John Webster picked it up.

“Your son has been shot by a Houston policeman,” the voice said.

“Is he dead?” Webster asked.

“Yes,” the man replied. “You have been informed.” Then he hung up.

The Father

A brief account of Randy Webster’s death ran in the Shreveport paper, as well as on the obituary pages of the Houston Chronicle and the Houston Post. Randy had stolen a van at Al Stokes Dodge on the Gulf Freeway in Houston, the papers said. Then he led police on a high-speed chase, finally spun out of control on Telephone Road, and emerged from the van pointing a pistol at the three police officers who had caught him. Patrolman Danny Howard Mays, who was assigned to the accident division and had never before shot a suspect, shot and killed him as officers Wayne Holloway and John Thomas Olin looked on.

In Shreveport, John Webster began to call Randy’s friends, ultimately piecing together the details of the story. He found out that Randy had been with a girlfriend Saturday night after he left home; that they had quarreled; and that sometime Sunday morning he and two friends had decided to drive down to Houston to visit Pat Kendrick, another friend from Shreveport who was working there and living in a rented trailer north of downtown.

On Monday afternoon, Randy drove to Al Stokes Dodge to look at the vans. While he was there he stole the keys to one that was on display on the showroom floor. Late Monday night, Randy and Pat Kendrick drove back to the Dodge dealership. Randy told Kendrick that he was going to steal a van and drive it back to Shreveport. Kendrick told him he’d never get away with it. Then Randy walked up to the dealership, broke one of its windows, got back in his car, and drove around the neighborhood for half an hour.

Then he drove to A1 Stokes Dodge. No alarm had sounded and no police had arrived. So Randy crossed the street, entered the dealership through the window he had broken, and got in the van. He started the engine and tried to drive through the glass door, but the van bounced backward instead of going through. So he backed up, put the car in gear, gunned the motor, and crashed through the glass-and-aluminum door. That was the last time his friend Pat Kendrick saw him.

Billie Webster was beside herself with grief. For months she simply wouldn’t accept that Randy had died. Every night she pretended that he was coming home, imagined that she heard him at the door. She hated having to face his friends when she encountered them at the local supermarket, and sometimes she left the store so she wouldn’t have to.

As for John Webster, he began to wonder more and more about the circumstances of Randy’s death. Certainly, he thought, Randy had been wild, but at heart he had been the scared type, not one to pick a fight. Had he been in his right mind on the night of his death—and the police had found four wrappers for the sedative Quaalude in his wallet, so maybe he wasn’t—Randy would not have pulled a gun on a police officer. That just wasn’t the kind of thing Randy would do.

So John Webster decided, in May 1977, more than three months after his son’s death, that he would find out more about what had gone on that night in Houston. First he called the Houston Police Department and made an appointment to see the two Homicide Division detectives who had investigated Randy’s shooting. He flew to Houston, where the two men told him, he says, that a grand jury had looked into the matter and decided not to indict Danny Mays, the patrolman who had shot Randy. In effect, the case was closed.

The detectives showed John Webster the gun that Randy was supposed to have pointed at the police officers. They said records showed the manufacturer had shipped the gun to a Houston discount store in 1964. Webster had never seen it before. He told the detectives that one thing was bothering him: why had Randy been shot in the head? Because, they said, policemen are trained to shoot to kill when their lives are in danger. Webster asked to see the Homicide Division’s report on the incident. The detectives explained that they couldn’t show it to him, but they read him portions of it. Were there any other reports he could see? Webster asked. Only the medical examiner’s autopsy and toxicology reports, the detectives said, but after looking for them they said the reports had been misplaced.

Webster had the feeling he was getting the runaround. He left the police station and went over to the medical examiner’s office to ask for the autopsy and toxicology reports on his son. A secretary there told him that they had not yet been transcribed from the tape on which they had been dictated. If he wanted copies, he could leave $15 and they would mail them to him in about a month.

Webster found that strange. The detectives at the police station had talked as if the autopsy report had already been written up. And if it hadn’t been written up, just how had the grand jury been able to determine that Officer Mays had done nothing wrong in killing Randy? Had they just taken his word for it? Webster was getting angry now, and he stalked out of the medical examiner’s office without even ordering the copies.

Then Webster went to the district attorney’s office and called on the assistant DA who presented police shooting cases to grand juries, a man named Tommy Dunn. A career civil servant, Dunn had been with the DA’s office for 23 years. He had handled thirty or forty police shooting cases before grand juries, never doubting for a minute that the officer had been in the right. He was very much a part of the law enforcement community. He knew what a tough job being a policeman was, and he had very little sympathy for criminals.

When John Webster came into his office, Tommy Dunn pulled out a file on the Webster case and leafed through it. He was surprised to see that it had not yet been presented to a grand jury. John Webster was amazed; just a few hours earlier, two police detectives had told him a grand jury had heard the case—apparently a bald-faced lie. Something strange was going on.

He asked Dunn whether he could find out if there had been any drugs or alcohol in Randy’s bloodstream at the time of his death. Dunn picked up the phone and called the medical examiner’s office. It turned out that the alcohol, barbiturate, and narcotics tests had all been negative. This piece of information seemed terribly important to Webster, because he couldn’t believe that Randy would have pointed a gun at a policeman unless he had been drunk or high on drugs. He felt certain that, if sober, Randy would have had the sense not to do that.

Dunn said the case would be coming before the grand jury the next month. Would there be any witnesses other than police officers? Webster asked him. Well, said Dunn, there was a taxi driver who had come forward saying he had seen the incident, but he probably wouldn’t be called—police investigators felt he had been too far away to have seen what happened.

“I can’t believe,” said Webster, “that my son would get out of that truck with three police officers chasing after him and point an unloaded gun at them. I think those policemen put that gun beside his body.”

“Why the hell would policemen put down an unloaded gun?” Dunn asked. He said he would believe the police version of the story until it was proven wrong. But he did give Webster the name of the taxi driver: Billy Dolan.

Webster left, got a fistful of quarters, and settled in at a pay phone to try to track down Billy Dolan. The closest he got that day was a supervisor at Yellow Cab who had been on duty the night of Randy’s death. He told Webster that Dolan had come in late that night looking badly shaken, saying he had seen a police officer “murder a kid.”

“Mr. Webster,” the supervisor said, “I believed him.”

The next morning Webster stopped by police headquarters and tried to see then Police Chief Pappy Bond, Assistant Chief B. K. Johnson, and Harry Caldwell, who had just been named to head the Internal Affairs Division. (The new division had been set up to investigate allegations of police misconduct in the wake of the death of a young

Chicano named Joe Campos Torres, who had drowned in Buffalo Bayou after he was beaten while in the custody of six police officers.) None of the three officials was available; Johnson’s assistant suggested that Webster write a letter stating his complaints.

When he got back to Shreveport, John Webster sent two letters to Houston by registered mail. The first requested a copy of Randy’s autopsy report from the medical examiner’s office. The second was to Assistant Chief of Police B. K. Johnson.

Webster wrote Johnson that a number of things had made him suspicious about the death of his son: the homicide detectives had told him the grand jury had investigated the case, when in fact it had not; three months after the shooting, the autopsy report had not been written up; Randy was supposed to have somehow obtained, without any money, a gun that had arrived in Houston thirteen years earlier; and then, cold sober, he had supposedly pointed the unloaded pistol at police officers.

“There are answers that my family and I need to help us through this nightmare with my son dead,” Webster wrote. “At the present time, my beliefs are that the gun and [Quaalude] packages were planted on my son after his death.” He asked Johnson to give the three officers who had been present at the shooting a lie-detector test to make sure their stories stood up. “This is a very small favor to ask in exchange for my son’s life.”

Johnson never answered the letter.

The Cover Up

June 20, 1977, was a typical sweltering summer day in Houston. It was already hot and humid when John Webster arrived at 201 Fannin Street at 8:30 a.m., and because the building was being renovated, the hallway outside the grand jury room wasn’t air-conditioned. Besides hearing the Randy Webster case, the grand jury also happened to be on a fishing expedition that day. They were looking into a widely circulated rumor that then Houston Mayor Fred Hofheinz had been arrested in a raid involving homosexuals or cocaine, or both, and that it had been hushed up. The rumor never proved out—it appears to have been nothing but character assassination by Hofheinz’ political enemies—but it generated a tremendous amount of interest, and the hall outside the grand jury room was packed with reporters and camera crews.

I too was in the hallway that day trying to check out the Hofheinz rumor, but I had also been looking into a rash of police shootings in Houston. I had clipped a newspaper story about Randy Webster’s death and had decided that at some point I would follow up on it. To learn more about the Hofheinz investigation, I was asking all the people present who they were and why they were there. I hadn’t known that the Webster shooting would be before the jury; I met John Webster and Billy Dolan, the taxi driver, outside the grand jury room, where they were sitting on a pewlike wooden bench. I introduced myself and began asking them questions and writing down answers in my notebook.

When the television reporters noticed me scribbling notes, they ambled over one by one to find out what was up, perhaps assuming that I had discovered a missing link in the Hofheinz caper. Disappointed on that score, they decided it was a story anyway. Barely six weeks after the death of Joe Torres, here were two men again alleging that Houston cops had murdered someone, and one of them claimed to have been an eyewitness. Jay Berry of KPRC-TV, Channel 2, was the first to summon his cameraman and film an interview with Billy Dolan.

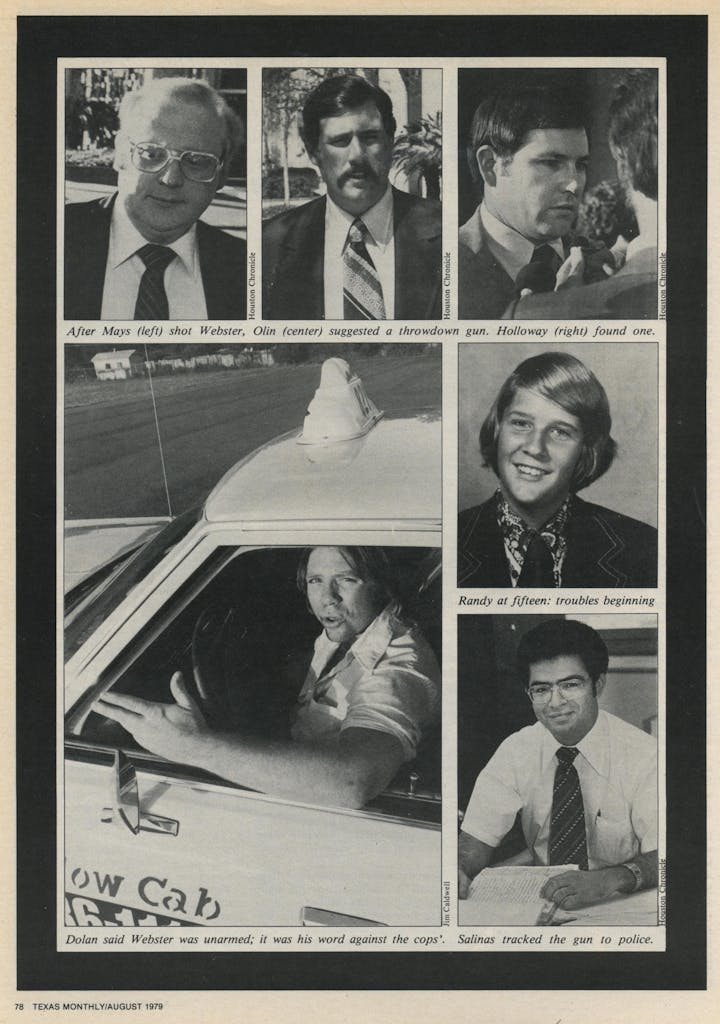

Those who turned on the local news that night saw a long-haired, unkempt cabdriver tell Berry that late one Monday night in February he had joined a police chase on Telephone Road to help apprehend a speeding van. He stated he had driven alongside the van at speeds of up to eighty miles an hour, hoping to cut it off. Suddenly, the driver of the van tried to turn, and the van stalled, skidded, and spun to a stop. One police car screeched to a halt just short of the van, its headlights illuminating the scene “so I could see everything,” and a second car stopped not far from the first.

One officer crouched with a knee on the boy’s chest, and a few seconds later, the cabdriver said, he heard a “kind of ‘puff’ sound, a muffled gunshot like when you shoot a watermelon, and I saw the kid twitch. He just killed that kid.”

A short, balding, red-haired officer (that would have been Mays) had quickly jumped out of the first police car and run toward the van, just as a long-haired teenage boy was coming out with his hands in the air “so I could see the space between his fingers.” The red-haired policeman yanked the youth out of the van, and he and a second officer threw him down on the pavement. The first officer crouched with a knee on the boy’s chest, and a few seconds later Dolan heard “a kind of ‘puff’ sound, a muffled gunshot like when you shoot a watermelon, and I saw the kid twitch. He just killed that kid.”

Then, as Dolan told it, one of the policemen shouted at him to get away, and he got back into his cab, gunned the motor, and sped off south down Telephone Road, afraid of what the officers might do to him. He drove out to Pearland, where he encountered a local patrolman and returned with him to the scene of the shooting. There Dolan talked with a police sergeant named Paul Dillon, who had arrived just after the shooting, and the next day he went down to police headquarters and told some homicide detectives what he had seen. “The police told me I lied about everything,” Dolan told the TV crews, “but I know what I saw.” Then, speaking for his fellow officers, Norval Wayne Holloway gave the reporters a description of events that matched the one in the newspaper stories right after the shooting and contradicted Billy Dolan’s.

The TV people also interviewed John Webster, and afterward he and Billy Dolan returned to the benches outside the grand jury room to wait in the stifling heat. Their tempers were wearing thin from the temperature and the long wait, and they were angry to see the three police officers who were present at Randy’s shooting ushered into Tommy Dunn’s air-conditioned office at the end of the hall.

Dunn had called the officers in because he wanted to go over their statements, something he hadn’t had a chance to do earlier. He was impressed by all three officers, and by Wayne Holloway in particular. “He was a bright, clean-cut young man,” Dunn recalls. “I remember thinking that he was the kind of officer we were lucky to have on the force.” The unkempt Dolan, in Dunn’s eyes, exuded untrustworthiness, while the policemen inspired confidence. “It’s almost impossible not to be swayed,” he told me, “when one side looks so good and the other so. . . scruffy.”

A little after three in the afternoon, after he had been waiting almost seven hours, John Webster was called into the jury room. The jury foreman, as Webster remembers it, started things off by “low-rating Randy, asking about his trouble with the law in Shreveport. I explained immediately that I didn’t condone stealing or think that my son was guiltless, but I said I had found some discrepancies that I thought ought to be investigated.” Several of the jurors seemed completely uninterested in what he had to say—“One man was doodling, and another was asleep or close to it,” says Webster. Just two of the jurors seemed to Webster to be genuinely concerned about what he was saying—a woman who had a teenage son and a black man in his mid-thirties. In less than fifteen minutes, Webster was dismissed from the grand jury room.

Billy Dolan didn’t even get a chance to testify that day. He sat on the bench all day, getting angrier and angrier, until late in the afternoon he was told to come back the following Wednesday.

Two witnesses came forward as a result of publicity following Dolan’s talk with the TV reporters. One was Bill List, the owner of a trailer business, who tended to corroborate Dolan’s story; but since he had been drinking and was dozing in front of the television when the sound of police sirens and gunshots awakened him, he was not a perfect witness. The other was Lexie Fate Daffern, a strong law-and-order advocate who worked as a checker on the early morning shift at the Santa Fe Trail Transportation Company off Telephone Road. His story was the opposite of Dolan’s and List’s: he said that while driving to work he saw the police chasing a van, pulled over, and saw a young man emerge from the van with “an object in his right hand.” In Daffern’s version, then, Randy Webster was carrying what appeared to be a gun, which implied that the police had shot him in self-defense.

In late June the grand jury, on the basis of the testimony of the police officers, the county medical examiner, John Webster, and Billy Dolan, decided not to indict Officer Danny Mays for the shooting of Randy Webster. In July, Tommy Dunn brought Bill List and Lexie Daffern before the grand jury, but their contradictory testimony didn’t move the grand jury to reopen the case.

The Stone Wall

John Webster was still sure that the officers’ version of the shooting of his son wasn’t true. He had learned through Pat Kendrick, the friend Randy had visited in Houston, that Randy hadn’t had a gun when he stole the van. And after the grand jury had decided not to indict, John Webster finally was mailed a copy of the medical examiner’s autopsy report. It said the fatal shot had been fired into the back of Randy’s head and that bullet fragments had passed downward through his brain. There had also been a bullet wound on the palm of Randy’s right hand. Webster called Tommy Dunn in Houston and asked him how Officer Mays, who stands five-foot-seven, could have stood face-to-face with Randy, who was six-two, and shot him in such a way that the bullet traveled downward through Randy’s head. And, he asked, why were there two wounds if the police only fired one shot at Randy, as they had testified? If there had been only one shot, the best explanation for the two wounds was that Randy had been shielding his head with his right hand. Dunn said the medical examiner had satisfied all the grand jury’s questions about Randy’s autopsy, and the matter was now closed.

Webster gave up on the local authorities. On August 25, he called the office of the United States attorney in Houston and said he wanted to file a civil rights complaint concerning the death of his son. He was told that such a complaint would have to be filed with the FBI. When he called the FBI in Houston to make an appointment, he was told that he could just as easily make the complaint at the FBI’s Shreveport office. When Webster went there, however, he was told to go home and write a letter stating the facts of the case.

In September 1977, this magazine printed my story detailing allegations of brutality by Houston policemen. One of the cases the article discussed was that of Randy Webster. It reported Dolan’s eyewitness account; noted that the police said Webster was shot in a standing position, but the autopsy showed the bullet’s path was downward through his head; and pointed out that the rifle Mays had reported sighting in the van apparently did not exist.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Mary Sinderson put a young man named Lupe Salinas in charge of the case. “I think there’s a throwdown gun in this case,” she told him. “If you can find it, I’ll give you a medal.”

In Houston, Mary Sinderson read the article with great interest. A tenacious woman who looks maternal but can swear like a truck driver, Sinderson had just been appointed by U.S. Attorney Tony Canales to head his office’s first Civil Rights Division. She sat down and wrote a letter to the Houston FBI office directing it to look into the circumstances of Randy Webster’s death, and she put one of her assistants, a young man named Lupe Salinas, in charge of the case. “I think there’s a throwdown gun in this case,” she told him. “If you can find it, I’ll give you a medal.”

Late in November 1977, Sinderson and Salinas decided to take the case before a federal grand jury. In the course of the hearing—some transcripts of which have since been made public—Mays laid out in detail his version of the shooting. He said he had been driving on the Gulf Freeway when he heard over his police radio that a van had been stolen from a nearby dealership. He pulled off the freeway and into a filling station on the adjacent service road to wait. It was about 2:30 a.m. on February 8, 1977.

Soon, Mays said, he saw a van heading north on the freeway and pulled behind it, his siren on and his lights flashing. The van sped up and small shards of glass, which he suspected were pieces of the dealership door, flew back at him. The van left the freeway at Woodridge, ran a red light, turned around, got back on the freeway going in the opposite direction, and exited again at Reveille. Police cars were waiting at the corner of Reveille and Park Place, but the van, said Mays, “just shot through the middle of them.”

Mays continued to chase the van, and was joined first by Holloway and Olin’s police car, and later on Telephone Road by Billy Dolan’s taxi. Careening down Telephone Road, the van suddenly spun to a stop. Mays stopped too, jumped out of his car, drew his gun, and fired several warning shots as he ran to the van. When he was four or five feet away, Randy Webster got out of the van. Mays said he heard one of his fellow officers shout from behind him, “Look out, he’s got a gun”; he saw the gun himself; and while “in the process of tackling him,” he shot Randy Webster.

Lupe Salinas, who was questioning Mays, asked him: “In other words, realizing that somebody was yelling—one of your colleagues had yelled, ‘He’s got a gun,’ and then yourself stating that you saw an object in his hand, you nevertheless tried to tackle him?”

“Well,” said Mays, “I was running at the time, like I said, it’s too late for me to stop, and I was right on top of the man. He was close enough to me. You know, I didn’t think about anything else. My firing my pistol was a reflex. I mean, I didn’t think about shooting him.” Salinas asked him again about the exact sequence of the tackling and shooting.

“Well, I don’t know how to explain how we got into this position,” said Mays. “But I had him down, and he was kind of on his side. . . . The second we hit the ground, there was somebody at his feet.”

“Just how long did that struggle last,” Salinas asked, “before you had to shoot him, or shot him?”

“I had already shot him.”

“When did you shoot him?”

“As I was jumping at him.”

“We’ll have to go over this again—”

Mays interrupted. “That is what I say. I don’t know when I shot him, but I shot him sometime between the time I first spotted him and the time I jumped . . . before I tackled him. Yes, sir, I would say I shot him before I hit him.”

After the grand jury hearing was over, Lupe Salinas telephoned John Webster, as he did frequently. He told Webster the case wasn’t going well—it was still the word of three confidence-inspiring policemen against two less authoritative eyewitnesses. “If it were me,” Webster recalls having said, “I’d put the heat on one of the policemen and hope that one of them would break the traces.”

The Gun

In late 1977, after the grand jury hearings, Mary Sinderson asked Lupe Salinas to close out the Randy Webster case. The investigation seemed to be going nowhere, and the U.S. attorney’s office was involved with other time-consuming matters. But Salinas asked Sinderson and U.S. Attorney Tony Canales for more time. He told Canales he wanted to trace the gun that had been found next to Randy Webster’s body. Canales gave him the go-ahead, but urged him to do it quickly.

When the Houston Police Department investigated the death of Randy Webster, its information about the origin of the gun came from a report by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, which said the pistol had been manufactured by a company in Connecticut and sold to Oshman’s, a wholesaler in Houston. Oshman’s, the report said, had shipped the gun to a Globe discount store in Southwest Houston, and from there it had gone, in 1964, to another Globe store on West 34th Street in Northwest Houston.

In 1974, when Salinas moved back to Houston from San Antonio, he had lived three blocks from the Northwest Houston Globe store, and he remembered that the store had opened about the time he had moved into the neighborhood. In other words, the federal agency had reported that the gun was shipped to a store ten years before that store existed. That meant the report was wrong.

Salinas asked Robert Ontiveros, a young man doing a criminal justice internship in the U.S. attorney’s office, to go down to the Southwest Houston Globe store and check its gun-sale records. Ontiveros asked to see the records for 1964, and he was given a big, dusty box of index cards. He went through them, checking serial numbers against the serial number found on the gun next to Randy Webster’s body. After he had been through more than eight hundred, he finally found a match. The gun had been bought from Globe in 1964 by a man named Roy Hooven.

There was no Roy Hooven listed in the Houston telephone book, but there was a William R. Hooven, Jr. Salinas called the number, and a Mrs. Hooven answered. She told him William R. Hooven, Jr., was the son of Roy Hooven, and that Roy Hooven had committed suicide in 1964 with a gun he had bought at a Globe discount store in Southwest Houston.

“What happened to the gun?” Salinas asked Mrs. Hooven. She replied that the police department had taken it when the family said they didn’t want it.

Salinas and Ontiveros were closing in. They went to police headquarters to find the suicide report on Roy Hooven and spent days searching through old records in two warehouses before they found it. The report said that a .22-caliber pistol with the same serial number and description as the one found next to Randy Webster had been tagged and placed in the police property room in 1964, after Roy Hooven’s death.

Salinas remembers feeling excited, nervous, and queasy as he looked at the report. The gun that Randy Webster had allegedly pointed at Officer Mays was the property of the Houston Police Department.

The Confession

Salinas told Mary Sinderson what he and Ontiveros had turned up, and together they told Tony Canales. Canales and Sinderson told Harry Caldwell (now chief of police), who quickly ordered an investigation by his Internal Affairs Division. The investigation revealed that according to police property-room records, the gun had been melted down in 1968, along with other unclaimed weapons. By early March 1978, the story of the gun had gotten out, first inside the Houston Police Department and then to the Houston papers and television stations. What now remained was to find out what had really happened that night on Telephone Road.

Salinas and Sinderson thought of the third police officer, John Thomas Olin. He had always seemed uncomfortable testifying, had not signed a statement after the shooting, and had abruptly terminated his interview with the FBI several months before. The two government lawyers decided to talk with him again about the shooting and the gun found next to Randy Webster’s body. They called Olin in, Salinas read him his constitutional rights, and they began to question him.

For fully ten minutes, Tommy Olin squirmed in his chair, looking anywhere but into the eyes of his interrogators. Did he want to call a lawyer? Salinas asked. No. Did he want to call his wife? No. He was just uncomfortable, Olin said, because there were so many officers involved. He paused again, and then said, “Well, obviously you all know that I’ve been lying.”

Olin told Salinas and Sinderson that Randy Webster had not been armed. Fueled by the tremendous adrenaline rush of the chase, Mays and Holloway had run from their police cars and thrown Randy to the ground. Holloway had gone to see whether there was anyone else in the van. Olin, meanwhile, rushed up and grabbed Randy’s waist, ready to pummel him. Just then—it happened so fast Olin wasn’t sure whether he saw it or only heard it—Mays brought his pistol down toward Randy’s head and the gun discharged.

Who put the gun down next to Randy’s body? Salinas asked.

“Holloway.”

“Where did the gun come from?”

Suddenly Olin clammed up. He said he wanted to see a lawyer. He left the U.S. attorney’s office, returning later that day in the company of not only his lawyer but also his father, brother, brother-in-law, and pastor. At this session an informal agreement was worked out: if Olin would tell the truth in front of a federal grand jury, he would get immunity from prosecution. The grand jury heard Tommy Olin on March 1, 1978, and there he went through his earlier testimony again, pointing out what had been true and what hadn’t. He also explained what had happened after the shooting.

“Mays stood back with a shocked look on his face,” Olin said. “I leaned over to see if [Webster] had been hit or if the gun had just went off and missed him or what…. I looked up and saw the cab driver approaching. I hollered for him to get back away from us. Then he stopped a minute and ran back to his car. Then Wayne (Holloway) came around and was hollering at him to stop.” At that point Billy Dolan quickly sped off.

Olin continued: “Mays, he was really shook up. We asked him, ‘What do you want to do? Do you want to use a gun or what?’ He just said yes, more or less. Like I said, he was about in shock.”

A supervisor from a nearby police sub-station, Sergeant Paul Dillon, had been the next person to arrive at the scene. Olin told the grand jury that he, Dillon, and Holloway had then discussed whether or not, considering that the cab driver had seen what had happened, they could get away with planting a gun on Randy Webster’s body, and they decided they could.

Soon, Olin said, Holloway had produced a long-barreled pistol, placed it in Randy’s hand while the boy was still alive and groaning, closed the fingers around it, and then placed the gun in the street. That way, they thought, if a trace metal test were performed (in fact, none was), it would show that Randy had held the gun. They also decided that if Holloway’s fingerprints were found on the gun (in fact, they weren’t), the explanation would be that Holloway had picked up the gun because Randy was still moving and might have grabbed it.

A few days later, Olin said, Holloway had told him the throwdown pistol had come from a police officer named William Byrd, who had arrived on the scene soon after the shooting. Nearly two months after Olin’s testimony Byrd pleaded guilty to concealing knowledge of a felony. He said he had found the gun in the glove compartment of a police cruiser and carried it around for years as a potential throwdown. He sometimes used it to hunt rabbits while he was on duty. (After the civil rights trial, Byrd’s plea was withdrawn and the charge was dismissed.)

Earlier, at the end of March, Lexie Fate Daffern, the civilian who had said he saw the shooting and had backed up the officers’ version of it, was indicted for perjury after he confessed to an FBI agent that he had lied and had arrived on the scene after the shooting. He was later sentenced to five years’ probation and fined $5000.

The day after Byrd’s guilty plea, Chief Caldwell fired Byrd, his partner, James Estes, Dillon, Holloway, Mays, and Olin from the police force.

The Trial

On June 2, 1978, the federal grand jury indicted Mays, Holloway, and Dillon. Mays was charged with violating federal civil rights laws by acting “under color of the laws of the State of Texas” to deprive Randy Webster of his life and liberty without due process. Holloway was charged with getting and placing a throwdown gun. Dillon was charged with lying about the shooting to authorities. In additional counts, all three men were accused of conspiracy to cover up the facts of the shooting and of perjury before the grand juries.

The case went to trial in February 1979, with U.S. District Judge Finis Cowan presiding. The trial would last six weeks. Cowan barred any evidence about the activities of Randy Webster before February 8, 1977, in order to prevent a defense based on Randy’s previous misdeeds. Mays’ lawyers, Ray Bass and Jan Fox, two associates of Racehorse Haynes’, presented an elaborate defense, suggesting that perhaps Olin or Holloway shot Randy Webster; that the government’s police witnesses were untrustworthy because they had “bought” immunity or reduced sentences from the prosecutors in exchange for testimony; that the government version of the shooting had internal inconsistencies; and that the cover-up couldn’t possibly have been hatched in the short time available. They maintained that there were too many loose ends remaining in the case to warrant a conviction.

Of the defendants, only Sergeant Dillon took the stand in his own defense. He appeared late in the trial and was an effective witness. At 38, he was older than the other officers, and with his short blond crew cut and military bearing, he had an air of honor and rectitude. The essence of his story was that when he arrived that night he had heard two versions of the shooting, the officers’ and Billy Dolan’s, and he had naturally decided to believe the officers.

After hearing a two-hour charge by Judge Cowan, the jury deliberated for six full days. By the sixth day, the defense lawyers were preparing to argue for a mistrial, but at five o’clock the jurors announced that they had a verdict.

Mays was found innocent of violating Randy Webster’s civil rights, but he and Holloway were both found guilty of the cover-up and of perjury. Dillon was acquitted on all counts.

The next day, when some of the jurors talked to reporters, it emerged that there had at first been some sentiment for convicting Mays on all counts, but it had subsided because the jurors were not certain that Mays had acted “willfully, knowingly, and intentionally” on the night Randy Webster died. And there was obviously a great deal of sympathy among the jurors for the young policemen. “Nobody wanted to convict the young men,” one juror told a reporter for the Houston Chronicle, “but we couldn’t get around the throwdown gun.”

About a month later, Judge Cowan passed sentence, assigning both Mays and Holloway five years supervised probation. In a seventeen-page memorandum that he read from the bench, Cowan said that the defendants had made “an initial panic-induced decision to twist the truth” and had persisted in it partly because of “loyalty to their comrades.” He considered Olin rather than Mays or Holloway “probably the most culpable”—apparently because it was Olin who asked Mays whether he wanted to use a throwdown gun. Cowan also used the sentencing as the occasion for a double-barreled attack on the government’s practice of granting immunity from prosecution to participants in conspiracies in return for their testimony. Although this statement failed to recognize that Olin had confessed his, Mays’, and Holloway’s roles to government prosecutors before he got a lawyer and bargained for immunity, Cowan’s attack on the use of immunized witnesses was hailed by a number of defense lawyers—including Percy Foreman, whose firm is suing the police officers and the City of Houston for $2.5 million on behalf of Webster’s parents.

All in all, there had been indictments and convictions in the case not because of any new policy in the running of the police force but because of a series of flukes: the tenacity of John Webster, Salinas, and Sinderson, the unusually complete sales records of the Globe discount store, the presence of reporters (because of the Fred Hofheinz rumors) at the first grand jury hearing, the publicity surrounding the Joe Campos Torres case, and Dolan’s happening to join the police chase.

There is, taking all that has happened after the killing into account, a theory of the case that holds that while the cover-up was wrong, the killing itself was certainly unfortunate but also understandable. Police work is hard and dangerous, this theory holds, and in the heat of a hard and dangerous chase regrettable accidents will happen. All wrong. Cops are the custodians of our laws; so they can do that job society gives them a badge, broad legal authority and privilege, and a gun. The least society can expect in return from the cop is a sense of purpose and a cool head. In part, these qualities can be developed by proper training, but far more important in developing them is the attitude of the force toward purpose and coolness. Randy Webster had led a fool chase, that is true; but he fired no shots, he emerged from his van with his hands high and his fingers spread wide enough for a witness to see the space between them. Then he was killed. There is no excuse for that, no excuse at all. Cops should be the first to disown and punish such actions. Instead, they planted a stolen gun by the boy’s body.

At the end of his opinion Judge Cowan noted: “It may be argued that the termination of this case without incarceration of a convicted officer has been a waste of government and judicial resources and an encouragement to officers to engage in reckless conduct.” Not so, he insisted, asserting that such a view was refuted by the “vigilance and persistence of the United States attorney’s office in discovering the records which made it possible to prosecute this case, the vigorous prosecution of this case, and high probability that similar situations will be thoroughly investigated by the authorities as well as the public.”

Although, given the Houston Police Department’s recent record, Cowan’s attitude may seem Pollyanna-ish, the Webster case has, nonetheless, made some difference. The word “throwdown” has entered the public vocabulary (in Houston, anyway), and with it has come the public’s awareness that some police officers may abuse the authority entrusted to them. The Houston Police Department’s property room has tightened procedures for “gun-burning,” the melting-down of impounded weapons, thus reducing the likelihood that another gun will leave the property room and be used in another criminal act.

Recently, the Texas Legislature stiffened the sanctions against police brutality; now, like the federal courts, state courts may impose a life sentence when death results from an intentional injury to a prisoner in the custody of a police officer, jailer, or guard. After the Legislature’s action, the Harris County district attorney’s office this summer set up its own civil rights division, making possible more systematic investigation of police shootings and alleged police misconduct than it has undertaken in the past.

But although the machinery exists to police Houston’s police, does the will? By disregarding or disbelieving Billy Dolan and Tommy Olin, the jury and judge concluded that what really happened on that damp February morning on Telephone Road was unknowable. They were not ready to say that Danny Mays had thrown a surrendering prisoner to the ground and was preparing to pistol-whip him when, accidentally or by reflex, Mays’ gun had discharged. The jury wasn’t ready to believe that the supervisor, Sergeant Dillon, had played a part in the cover-up. The judge was quick to point out that Randy Webster had threatened the officers’ lives by leading them on a high-speed chase.

The facts in such cases are seldom any more clear-cut than these were; indeed, they are seldom as clear. Like this one, most juries are disposed to believe the accused officer.

John Webster, after two years of searching for the truth about his son’s death, had come as close to finding out what happened as anyone might hope to do. But on the day the jury convicted the officers of cover-up and perjury, he was not vindicated, not satisfied, but bitter. “Those twelve people on the jury,” he told reporters after the verdict was handed down, “are telling Houston policemen they have a free hand—just go ahead and kill anyone you want to.”