In November 2012 Bob Kaluza was in Houston meeting with the defense lawyers that his employer, the British oil giant BP, had hired on his behalf. Two and a half years earlier, Kaluza had been one of two BP supervisors on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig the night it exploded, and he was worried that the federal government would hold him responsible. Yet in the intervening months, no charges had been filed against him. It was beginning to look as if hiring a legal team had been an unnecessary precaution.

Then, one of his attorneys stepped out to speak with a colleague. A few minutes later he returned, with bad news: the federal government was indicting Kaluza on 22 felony manslaughter charges and 1 misdemeanor for his role in the worst offshore oil disaster in American history. “I just sat there stunned,” Kaluza says. “I did nothing wrong. None of us thought they were actually going to go after the well site leaders.”

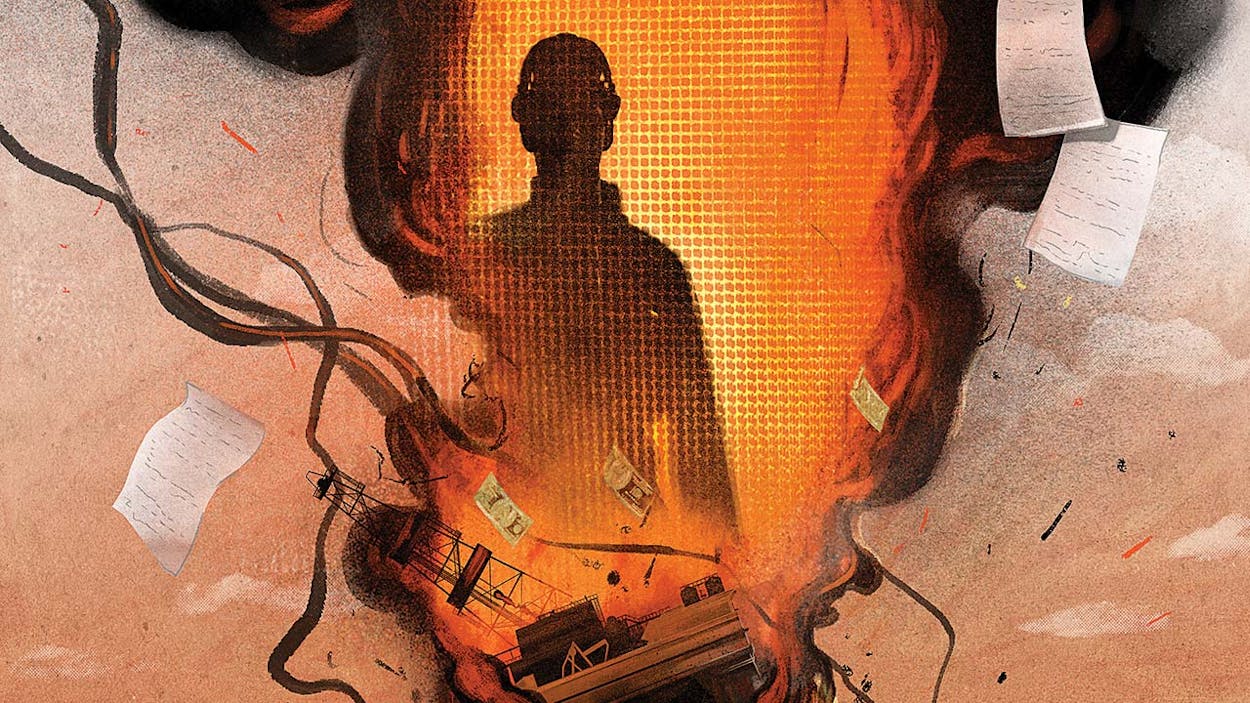

The Deepwater Horizon blew up on April 20, 2010, killing eleven men. By the time it sank and settled onto the floor of the Gulf of Mexico, the search for who was responsible had already begun. Weeks after the explosion, President Obama told NBC’s Matt Lauer he was trying to figure out “whose ass to kick.”

By late 2012 it was clear whose that would be: Obama’s Justice Department had set its sights on Kaluza and his fellow BP supervisor, Don Vidrine, who was indicted on the same charges. The two men were the lowest-ranking BP employees associated with the accident (most of the crew were employees not of BP but of the Houston company Transocean, which owned and operated the rig). “I got caught in the vortex,” Kaluza says, discussing the case for the first time from his home, in Henderson, Nevada.

Kaluza and Vidrine were trapped between two powerful forces: the public outcry to hold individuals accountable and what some saw as BP’s desire to ensure that those individuals weren’t high-ranking executives. In both the civil and criminal litigation that followed, BP, whose American headquarters are located in west Houston, moved quickly to head off its liability. It pledged $20 billion to pay civil claims from Gulf Coast residents whose livelihoods were hurt, and its plea agreement with the government was announced just as the indictments against Kaluza and Vidrine were unsealed. In the agreement, BP acknowledged that mistakes were made, but the only individuals it singled out for blame were Kaluza and Vidrine, who, it said, “negligently supervised” a critical pressure test and failed to notify company engineers of possible problems with it, “in violations of the applicable duty of care.” All of which, BP claimed, led to the explosion.

Such accidents, however, are rarely the fault of just a few individuals. Offshore drilling is a complex operation that involves hundreds of people; 126 people were employed on the Horizon drilling the Macondo well on the day of the accident. By then, the project was already running six weeks behind schedule and some $58 million over budget. Everyone was under pressure to finish drilling and get the well into production.

The Justice Department, however, focused on Kaluza and Vidrine, saying that their failure to prevent the accident was a criminal act. “There’s always been plenty of proof that criminal negligence took place,” says Keith Jones, a lawyer in Baton Rouge whose son, Gordon, was killed in the blast. “What we couldn’t prove was who and when.”

In Kaluza’s version of events, he and Vidrine appropriately handled the two pressure tests that were conducted that day; the disaster was caused not by them but by bad well design and upper-level managers who were more focused on saving money than on drilling safely. The government saw it otherwise and indicted both men on eleven counts of involuntary manslaughter, eleven counts of something called “seaman’s manslaughter,” and one misdemeanor count of violating the Clean Water Act. “Eleven guys died, and they indicted the defendants on twenty-two felony counts,” says Shaun Clarke, one of Kaluza’s attorneys. “It’s like saying they killed them twice.”

Kaluza, who was sixty at the time of the accident, has worked in the oil business since he was eighteen. A native of Williston, North Dakota (where NBA great Phil Jackson once coached him in baseball), he roughnecked his way through college, earning a business degree from the University of North Dakota and later an MBA and a bachelor’s in petroleum engineering. He joined BP in 1997 as a drilling engineer, and in 2001 he attended an offshore training session aboard the then-new Deepwater Horizon. Kaluza liked working on the offshore facilities. Though he was a company man, he felt as if he fit in on the rig; his time as a roughneck and tool pusher helped him develop a rapport with other rig workers.

On April 16, four days before the disaster, Kaluza, who was working elsewhere in the Gulf, was sent to the Horizon to relieve the regular company man, who had to renew his training certification. On April 20 he worked the day shift, and after Vidrine came on deck at 6 p.m., Kaluza stayed topside for about two more hours before going to bed. At 9:49 p.m., he was startled awake by a fire alarm, followed by a blast that shook the rig. He tried to turn on the lights, but there was no power, and he fumbled around in the dark for his hard hat and steel-toed boots. Stepping out of his room, he attempted to make his way to the lifeboat, but the hallway was blocked with debris. He turned around and kept walking, unsure of where he was going, and stumbled upon a crew member with a flashlight, who led him to the lifeboat. Once in the water, the boat made for a nearby supply ship. Kaluza says that at the time, he was simply concerned with getting everyone off the rig safely. “I saw many people close to panicked,” he recalled. “It was my duty to keep my composure and get people calmly onto that lifeboat—and we did.”

Onboard the supply ship, inspectors from the Minerals Management Service (MMS), the federal regulator for offshore drilling, debriefed him. Kaluza, running through the day’s events, told them he didn’t believe anything had been amiss. “Everything went according to plan,” he said.

Five months later, Kaluza, who was on paid leave from BP, got a hint of what was coming. He was reading BP’s internal investigation of the accident and felt increasingly uneasy as he pored over it. He says that BP investigators had never talked to him, and he was concerned with what he regarded as gaps in the document; there was no mention of the failures of upper management or problems with the rig’s design, even though it was clear to many that both had played a role in the accident. He concluded that the report’s purpose wasn’t to determine what had gone wrong but rather who should take the fall, and the document was pointing a finger at him and Vidrine. “My company was trying to blame me,” Kaluza says. “That’s when I knew I was on my own.” (BP did not respond to requests for comment.)

BP’s initial investigation into the 2005 explosion at its Texas City refinery, which killed fifteen people, came to a similar conclusion, blaming control-room operators. But a later investigation by the U.S. Chemical Safety Board faulted BP’s cost-cutting culture for neglecting maintenance and compromising safety. After the Horizon disaster, however, BP’s findings became the basis for many of the investigations that followed. Much of the civil trial—which began in 2013 and rolled up dozens of lawsuits brought by businesses, state governments, and individuals—operated under the assumption that Vidrine and Kaluza had at least some culpability.

“The government took the easy way out because it was laid out for them,” says Michael Doyle, a Houston attorney specializing in maritime injury law who was not involved in the case. “BP was happy to use the company men as scapegoats.”

Kaluza could afford a topflight legal defense because BP, as his employer, was obliged to foot the bill. The company hired a high-powered Houston legal team for him that included David Gerger, who is perhaps best known for defending Enron’s Andrew Fastow. One fruitful avenue the attorneys followed was researching the origins and use of the charge of seaman’s manslaughter. Gerger’s co-counsel, Shaun Clarke, found it had been designed to hold steamship captains and crews accountable for reckless behavior after a series of fatal accidents on the Hudson River in the nineteenth century. He argued that even though the Horizon was technically a ship, Kaluza and Vidrine were supervisors of the drilling team, not the ship’s captains or crew. The judge agreed and threw out those charges.

That still left eleven counts of manslaughter and the misdemeanor; if convicted, Kaluza and Vidrine would possibly spend the rest of their lives in prison. But as the case progressed and some prosecutors left the DOJ for private practice, public outrage and the government’s desire for prosecution seemed to fade. In addition, several later independent investigations had found that the accident had numerous causes, including issues with the well’s design and some of the rig’s safety equipment. Convincing a jury that two individuals were criminally liable for the disaster looked difficult. The feds dropped the manslaughter counts, which left only the misdemeanor water pollution charge. They pushed both men to accept a plea deal on the misdemeanor, which had been offered earlier. Vidrine accepted, paying a $50,000 fine, serving ten months’ probation, and performing 100 hours of community service. Kaluza refused. “There’s no one who’s going to talk me into saying I did something I didn’t do,” he says.

The trial on the remaining misdemeanor charge started in February and included several pieces of evidence that had not turned up in any of the 91 million pages produced during the civil trial. First, the DOJ presented a tape of the interview that Kaluza did with MMS inspectors hours after the blowout. While prosecutors thought Kaluza’s statement would reinforce their negligence claims, it allowed jurors to hear him explain what had happened in his own words. As a result, the defense didn’t have to put Kaluza on the stand and expose him to cross-examination. “That was a gift from the prosecution,” Doyle says.

Kaluza’s attorneys also told the jury that he wasn’t on duty at the time of the explosion, having gone to bed almost two hours earlier. “None of us would have gone to bed if we knew there was anything wrong with the well,” Kaluza now says.

One irony of the case was that defending Kaluza meant that the lawyers spent a fair amount of time attacking other, higher-ranking employees of the company that was paying for their services. Vidrine testified that hours before the explosion he discussed the results of the pressure tests with Mark Hafle, an engineer in BP’s Houston office. Clarke, Gerger, and their third co-counsel, Dane Ball, put on the stand an expert who had examined Hafle’s computer and testified that Hafle was booking airline tickets while talking with Vidrine rather than looking at the real-time data from the well. Hafle didn’t log in to check that data until after the blowout.

Vidrine was also involved in the trial’s trickiest moments. As part of his plea, Vidrine agreed to testify against Kaluza. (Kaluza says he has no bitterness toward his former colleague, because the pressure from the government was immense.) Although Vidrine was a government witness, Gerger’s gingerly cross-examination essentially turned him into a witness for the defense. Among other things, Gerger clearly established that Vidrine was following the procedures set out by BP’s engineers in Houston. By the time Vidrine stepped down, his statement that he had been negligent, made under direct examination by prosecutors earlier that same day, rang hollow.

In the end, jurors didn’t buy the government’s case. On February 25 they acquitted Kaluza, who claims he never doubted that he would be found not guilty. “If you did nothing wrong, you should never say you did,” he says. “You stick to your morals.”

In all, the Justice Department brought 48 felony charges and 2 misdemeanor charges against four BP employees: Kaluza, Vidrine, former BP vice president David Rainey, and an engineer named Kurt Mix. The result: two acquittals and two misdemeanor guilty pleas. “The Justice Department came up short because it largely targeted individuals who were too far down the corporate hierarchy to be compelling defendants in a case that involved a corporate culture run amok,” says David Uhlmann, the director of the Environmental Law and Policy Program at the University of Michigan and the former chief of the Justice Department’s environmental crimes section. “It’s never easy to prosecute senior corporate officials for catastrophes like the Gulf oil spill, but that does not justify going after low-level officials who had no say in misplaced corporate priorities.” (The DOJ declined to comment on these cases.)

The Deepwater Horizon is about to return to the public consciousness with the release of a movie by the same name. The film, starring Mark Wahlberg, highlights the heroics of the crew in getting the 115 people who survived the explosion off the blazing rig. Kaluza says the filmmakers never contacted him, and he doubts he has much of a role since he was in bed at the time of the accident. Nevertheless, he’ll probably watch it, “just to see what Hollywood can get away with.” Kaluza took a buyout from BP a few years ago, and he’s working on a book about the accident, which he intends to turn into a TED talk. With the legal saga behind him, he would like to return to the oil business.

As he reflects on his case, though, one thing strikes him as odd. BP paid for his defense, yet the company has had nothing to say about the jury’s verdict. “I haven’t heard a word of congratulations,” he says. “I’m still waiting.”