Listen to this episode on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. Read the transcript below.

Learn more about the case with original videos, archival photos, and documents from our reporting in our episode guide.

Subscribe

“For thirty or sixty days, a lot of things were left undone. . . . When you lose that initial time and it’s not being proactively investigated, it’s hard to overcome.”

Nick Hanna

In this episode, investigators Larry Counts and David Jones detail their initial steps in trying to solve the case—and share the story of how Shane and Sally started speaking with the authorities just months before they were killed. Then, officials at the Tom Green County Sheriff’s Office today share their frustrations with the initial investigation, and detail the surviving evidence from the crime scene.

Shane and Sally is produced and cowritten by Patrick Michels, and produced and engineered by Brian Standefer. Assistant producer is Aisling Ayers. Story editing by Rafe Bartholomew. Executive producer is Megan Creydt. Fact-checking by Doyin Oyeniyi. Studio musician is Jon Sanchez. Artwork is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Get in Touch

If you’d like to share any thoughts about the podcast, or about the murders of Shane Stewart and Sally McNelly, let us know in the form below.

Transcript

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): Three years after Shane and Sally were murdered, the case was featured on the TV show Unsolved Mysteries. In the show, there’s a reenactment of the scene we described in our last episode.

The one where former sheriff’s deputy Larry Counts visited Shane and Sally’s apartment to get a gun from Sally. She’d heard this gun was used in a murder. And Sally just wanted to get rid of it.

The scene is set in March of 1988, just a few months before the murders . . .

Actor as Sally: Shane, he’s here.

Actor as Shane: Okay.

Actor as Sally: He’s trying to find the gun.

Larry Counts: Okay.

That’s Larry’s voice saying “okay” there. He played himself in the episode.

For all the attention the murders had gotten, all the pleas for help on local TV, this was the first time the gun story became public.

Actor as Sally: This is the gun that guy gave us that I told you about.

Larry Counts: Okay. Did he have any other weapons?

Actor as Sally: Yeah, he’s got a whole toolbox full of guns. I mean it’s scary because you know these guys are . . .

In the episode, we never hear who gave Sally the gun, but whoever he is, she’s worried about this guy. And Shane is worried the guy might hear they gave the gun to the sheriff’s office.

Actor as Shane: He’s not going to find out about this, is he?

Larry Counts: I can’t promise you anything, but I will do my best.

Actor as Shane: Well, I appreciate it.

At least for the cameras, Larry said he’d do his best to keep it secret. But today, he thinks it’s possible that someone did find out—and that’s what got Shane and Sally killed.

Back at the sheriff’s office, Larry traced the gun’s serial number. Turned out, it had been stolen, in 1984, from an Army surplus store in San Angelo.

And, because Sally told him it’d been used in a murder that took place within the city limits, Larry passed the gun to the San Angelo Police Department. And he gave them Shane and Sally’s names.

Larry told me he’s come to believe there was a leak in the city police department, someone with connections to whoever gave Sally that gun. He mentioned this just as we were packing up to leave, so it’s a little hard to hear . . .

Larry Counts: Yeah. And then . . . If we brought somebody in, and had an interview with them, then maybe like the next day, this policeman would come in, and [say,] “Hey, how’d your interview with so and so go?” Or stuff like that. And that’s what got us wondering how he knew everything that was going on.

Rod D’Amico (voice-over): I wanted to know more about Larry’s theory. It’s a startling accusation for one lawman to make against another. And to me, the key piece of evidence seems to be the gun. So I filed an open records request with the city police. But they told me they couldn’t find any records about this gun. I figured, surely someone who worked there back then would remember it.

I found one former officer, who gave me a list of names. I mined old crime stories in the San Angelo paper for more officers’ names. Then I started calling. And after an endless string of wrong numbers, I finally reached one of them. Then another. Eventually, I’d talked with more than twenty people who’d worked at the San Angelo Police Department around this time.

Rob D’Amico: Yeah. Do I have the right Phil Fox, the form—

Phil Fox: The one and only.

Rob D’Amico: Well, I’m a reporter . . .

A retired officer named Phil Fox told me, yeah, he did remember the Shane and Sally case—but only that it was the sheriff’s office who investigated it, not the city police.

Phil Fox: As far as the gun, I don’t recall anything about a gun. I remember the case that you’re talking about now, cause it’s been a long time ago . . .

Dennis McGuire: You’re trying to find out what now?

I heard pretty much the same thing from Dennis McGuire . . .

Dennis McGuire: The gun was given over prior to their death? See, I didn’t even know that. I wasn’t aware of a gun. So . . .

. . . and from David Howard . . .

David Howard: I do not recall anything about a gun being turned in to us. And I don’t have an answer for you, surely there’d be some paperwork associated with that gun.

. . . and from Frank Carter Senior . . .

Rob D’Amico: You don’t recall any gun being turned over?

Frank Carter: No, sure don’t. . . . but those kids lived in my neighborhood and they’re all, I thought, good kids. I don’t know. It’s a mystery. I know that.

The stolen gun, a .25-caliber pistol supposedly used in a murder. An eighteen-year-old girl gives it to the sheriff’s office, and starts talking with the authorities, just before getting murdered, in a case that made national headlines. You’d think that someone would remember this gun.

I even talked to Taylor Cole, who runs the store where the gun was stolen: Cole’s Army Surplus.

Rob D’Amico: Are you aware of the Shane and Sally case?

Taylor Cole: I’m not aware of that case, but we’ve been broken into quite a few times.

He told me he wanted to help, but since the gun was stolen in 1984, he knew there wouldn’t be any records left at the store.

Taylor Cole: In 1986, my dad had just bought out his father and it all came crashing down that night. I sat and watched it burn.

Their store, and all the records inside it, were lost in a fire. They’ve rebuilt since then. Neither he nor his dad remember this missing gun. But now he was curious what had happened to it. I had to break it to him:

Rob D’Amico: There’s no records on it. Nothing. So . . .

Taylor Cole: The gun disappeared?

Rob D’Amico: Yeah, it’s gone.

Taylor Cole: Oh. So that means I can’t get my gun back.

Were Shane and Sally killed for turning in this gun and telling the police about a murder in town? And were members of the San Angelo police involved in their deaths? That’s one theory—one that Larry Counts believes. But without records of the gun, or a single police officer who remembered it, I was getting worried this might be a dead end.

But even back in 1988, investigators had other theories as well.

We’re going to talk about how those first investigators tried to solve the murders of Shane Stewart and Sally McNelly. What leads they chased. What leads they, apparently, didn’t. And how this became the kind of “cold case” that generations of sheriffs and Texas Rangers, and reporters with podcasts, keep coming back to over the years, searching for crumbs that everyone else missed, hoping for a break.

From Texas Monthly, this is Shane and Sally. I’m Rob D’Amico . . .

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): And I’m Karen Jacobs. This is episode three: “An Open Investigation.”

Back in 2018, I was talking with Terry Lowe, who was an investigator with the Tom Green County Sheriff’s Office, and he told me something about what it would’ve been like as an investigator in the summer and fall of 1988.

Terry Lowe: The thing is, I think this, if Shane and Sally happened today, it’d be solved probably by tomorrow. But, unfortunately, things were different.

He said San Angelo is bigger now. The sheriff’s office has more investigators, and those investigators have better tools, like forensic technology, access to social media, cellphone records.

Terry Lowe: You know, it’s a different world in law enforcement than it was back then, yeah.

Terry told me a story from years ago, when he was working in Midland, a bigger city a couple of hours northwest of San Angelo. He was watching a true crime series on TV, and a detective in California was describing a novel way to find blood at a crime scene, with ultraviolet light.

Terry Lowe: So the next day I called him from Midland, and I said, “Hey, I saw where y’all used an alternative light source to look under blood, and I’m working a case where I think that will help me.” He said, “When did you see this?” I said, “I saw it last night,” and he said, “That was eleven years ago.” So it took eleven years and a television show for me in Midland, Texas, to learn that that even existed.

In July 1988, the sheriff of Tom Green County, Texas, was Ernest Haynes. In his office, the lieutenant in charge of criminal investigations was named Lou Hargraves. There were just a few deputies. One of them was Larry Counts.

Karen Jacobs: So tell me, what was it like in 1988? What was going on in San Angelo? Was it busy or sleepy or—

Larry Counts: Well, for the sheriff’s office, it was kinda slow, actually. We had an occasional homicide. For the most part, it was, back then, it was a relatively sleepy little country kind of a county.

Larry has wire-rimmed glasses and neatly combed hair, just like he wore it back in the eighties. Back then, he was just a patrolman at the start of his career.

Larry Counts: And I happened to be working the morning that the lake ranger called, he had that vehicle out there. And so I was one of the officers that went out there.

Karen Jacobs: And what were your first thoughts?

Larry Counts: Because there was . . . Everything was kinda neat in the car, and neat around it. There was no signs of struggle and stuff. We originally thought they just broke down somehow, and that it was just left out there. Then we contacted his dad, and his dad said, “No, it’s not broke down.”

Marshall Stewart told us about this, too, how he kept pressing investigators to search around Shane’s Camaro, to treat it more like a crime scene, and they told him Shane and Sally had just run away. But Larry says he never really believed Shane and Sally just skipped town.

Larry Counts: We got a report that they were seen at a truck stop somewhere, like they were hitchhiking or something, but that never made any sense, either. I mean, he had a perfectly good, nice car that a teenage boy would love to have, and why leave it?

Two other detectives worked the case with Larry. He says they were the primary investigators. One was his lieutenant, Lou Hargraves. Another was named Bill McCloud. Both of them have since passed away.

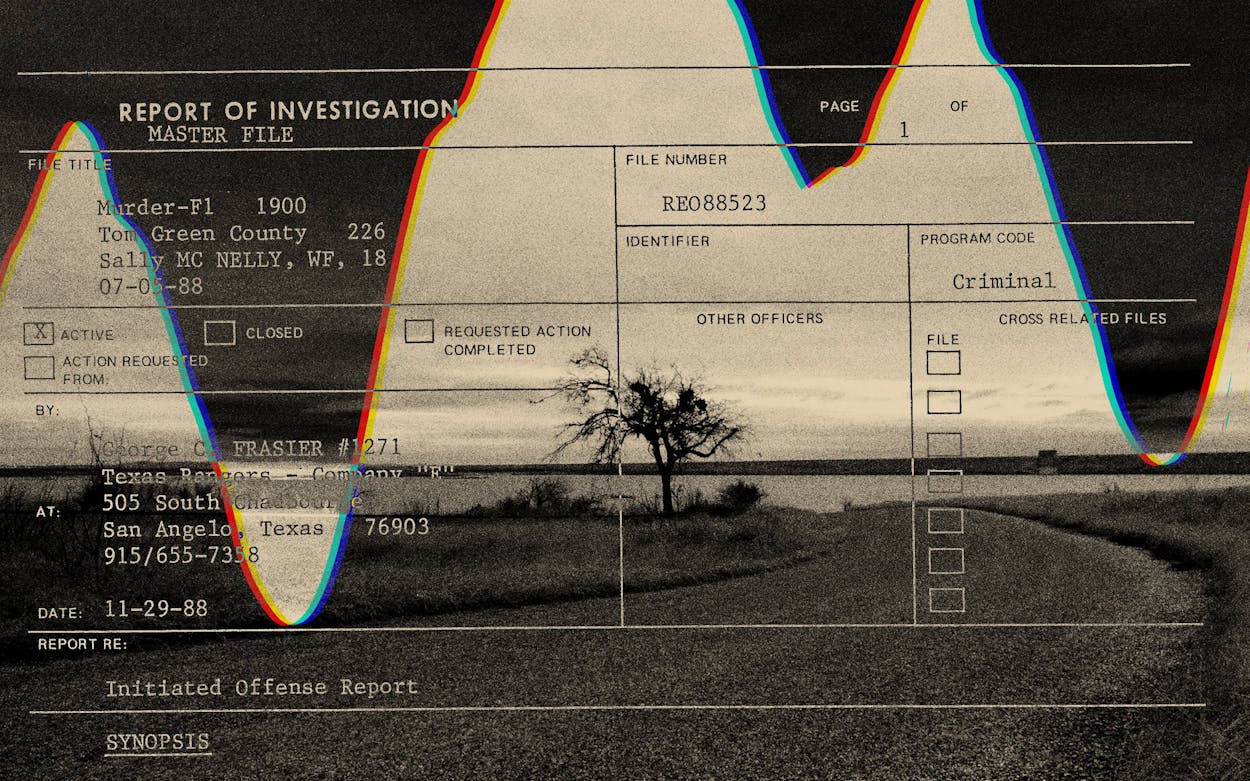

Together, they assembled a timeline of where Shane and Sally were in the weeks before the murders, right up to the night they went missing. This timeline is one of the key documents we have from the initial investigation. And it mentions at least 25 interviews they conducted, into late December 1988.

Larry Counts: And we had started checking out with their friends, and the people that they ran with.

Karen Jacobs: Did you think about the stories about the satanic stuff at all?

Larry Counts: Yes. Yeah. Because two or three of their friends were kind of . . . were more involved in the satanic angle. Yeah, we did think that that might have something to do with it.

Actually, some of this Larry had heard directly from Shane and Sally. After they gave him that stolen gun, Larry says they offered to tell him more about this occult group.

Larry Counts: They told me or showed me a couple of places where satanic rituals were supposed to have taken place. Some of it was out in the county. One place was here in town, here in San Angelo. The other place where they told me was very near where their car was found later, when they turned up missing. Out by the lake.

That’s O.C. Fisher Lake, around those picnic tables that Marshall filmed, with the spray-painted pentagrams and heavy metal band names. Larry says he investigated the group of kids who hung out there, and heard some outlandish rumors, but never found evidence to support them.

Larry Counts: You know, there was never any crime that was actually, we could say was . . . the crime was done because of somebody being a satanic worshipper. And I think a lot of it was just kids.

Those old interview notes mention some people with records of pot possession and petty crime, as well as the fact that there was tension in the group. In particular, the deputies heard that there were some people Shane and Sally weren’t getting along with.

One of those leads came from Marshall. He told us about this too . . .

Marshall Stewart: And then the night of the Fourth when he disappeared, there was a phone call and I answered it in the kitchen. It was a phone call for him, and I didn’t recognize the voice on the phone. And so I just said, “Shane, you’ve got a phone call.” So, I walked kind of down the hall and just stood there to listen, because I’m thinking, “Well, they just come back to town a day or two ago, who would know that he’s in town?” And as I was listening, he said, “Hey, I’ve got your money. Don’t worry about the money, that’s not a problem.” So when he hung the phone up, I told him, I said, “If you owe somebody and you’ve got money in there, you need to go ahead and pay them.” He said, “Hey Dad, it’s not a problem, not a problem at all.” I said, “Okay.”

So I asked Larry what they did with that information.

Karen Jacobs: So was that something you followed up with when you couldn’t find him?

Larry Counts: Yes. Yes. Now, back in that time, it was hard to trace any telephone calls, not like you can now. As far as I remember, we never knew who made that call. And as far as money, I mean, it’s possible he could’ve owed somebody money for something.

Karen Jacobs: No one ever found a large amount of cash on Shane or anything like that.

Larry Counts: No. No.

It might’ve been hard to find out who made that phone call, but it was possible. And we haven’t seen any record that anyone at the sheriff’s office did.

The sheriff’s eight-page summary of early investigative work is kind of frustrating. It raises tantalizing questions that are never answered. It mentions so many interviews, so many leads, and so few conclusions.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): The sheriff’s office also had physical evidence to work with. But—and you’ve heard a little of this from Marshall already—there were major problems with how they handled that evidence, mistakes that modern investigators can never go back and fix.

First, there was Shane’s Camaro, and the area around it at O.C. Fisher Lake. In the reports we have, detectives did make a list of what was in the car: the keys on the dash, the fast food wrappers, and Sally’s work uniform.

But the report doesn’t have any photos from the scene, and Marshall doesn’t remember seeing the detectives take any. And those big tire tracks next to the Camaro—Marshall says he insisted the officers examine them, but there’s no record that the officers took notes or photographs or made casts of the tracks.

And then they just let Marshall drive the car home. It was days before they called and asked him to bring it back to the station for a more thorough search.

DNA analysis was still years away in San Angelo, but by 1988, investigators were trained to collect fingerprints and hair, and fibers from clothing—the kind of evidence that you can lose forever if you let someone drive off with a car.

But even evidence that did make it to the sheriff’s office had a way of going missing. Sally’s stepfather Bill Wade told us that—like Marshall—he and Pat got lots of calls from people claiming to have information. Bill figured the best thing they could do was just take notes on everything, and pass it all to the sheriff’s office. Basically, leave it to the professionals.

Karen Jacobs: Like, you mentioned giving them notes and you were having calls. What happened with all that stuff?

Bill Wade: As far as we know it vanished. We had our written notes about people that called us and we’d acquired an answering machine to record calls. We turned over tapes of calls to Larry Counts. Honestly, we gave them everything we had. None of that stuff that we gathered is in our possession anymore. We have to dredge our memory and bounce ideas off of each other to try and remember details when Terry asks, “Hey, did you know X or did you know Y?” It’s like, “God, I don’t know.”

In November of ’88, the deputies were faced with the most critical evidence of all, when the search for Shane and Sally ended, with that call from a hunter at Twin Buttes Reservoir.

Larry Counts: So he walked over to a little grove of trees, and as he stepped around, he walked up on Sally’s body laying there. It was still clothed, but of course, then all the flesh had all decomposed, so it was just, actually, a skeleton dressed in clothes.

Larry says it looked like whoever had killed them tried to hide the bodies under piles of branches.

Larry Counts: And maybe at the time, in July, when the branches were put on them, they may have had leaves on them and stuff, but by that time in November, all the leaves had fallen off and stuff, so it was just bare branches on top of them, and neither one were even attempted to be buried.

Their bodies were 75 feet apart. Investigators recovered shotgun shells and buckshot on and around the remains.

Larry Counts: Well, we photographed everything at the scene, and then we took a . . . like a piece of thin board, and we slid it under the body, and scraped up all the dirt along with it, and then put that in the body bag so when we went to San Antonio to the ME’s office, we had the dirt underneath the body and stuff, too.

Their photos from the scene are still with the reports we have. And thanks to these photos, we can also see that officers were handling evidence with their bare hands—which they would have known was a big mistake even then.

In one photo, an officer holds—in his bare hand—a shiny, silver hat pin. The pin is shaped like a branding iron; on one end are the letters “JBS,” which stand for “John Batterson Stetson,” as in the Stetson hat company. A report says this pin was found lying on top of the brush that covered Shane’s body.

Near the bodies, officers also found a spot that looked charred, like someone had lit a campfire. And near it, they found the remains of a black cat—which they shipped off to the medical examiner too, though it didn’t yield any more evidence. Investigators mentioned both the cat and the fire pit as potential evidence of cult activity.

I’ve had numerous conversations with officials who say the sheriff’s department had made mistakes in the initial investigation.

I went back to Larry last summer to ask him about all these times it looked like the sheriff’s office had dropped the ball.

Larry Counts: Okay. I don’t want to say anything bad either, but Bill and the other two detectives were very scatterbrained. And I was just a patrolman. Because Shane and Sally came to me first, then they brought me into it, but I was just a patrolman. I wasn’t a detective. And you’d bring stuff to them and they wouldn’t, they just flat wouldn’t write reports and stuff, but we were interviewing people, yeah.

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): By early 1989, though, the sheriff’s office wasn’t the only one looking into the case. After the bodies were found, the Texas Rangers and an investigator with the state police began looking into it as well. The investigator’s name was David Jones.

David passed away in 2021, but I was able to interview him in San Angelo six years ago. He told me he heard about Shane and Sally’s disappearance pretty quickly, and once he saw the facts of the case, he didn’t believe they just ran off together.

David Jones: I know the sheriff’s office at the time, that was their opinion. It wasn’t my opinion once I became involved and knew the facts of the case.

David began interviewing people and writing detailed reports about what he’d learned. David took a close look at the eye-witness account of Randall Littlefield, the fisherman you heard about in episode 1.

At first, Littlefield’s story was pretty clear-cut. He said he was out fishing when he saw Shane and Sally sitting on Shane’s Camaro, then saw two young men in a small pickup truck drive up and start arguing with them.

His account became key to the investigation. But there were problems with it. For one thing, Littlefield didn’t come forward until the spring of 1989, long after the Fourth of July.

It’s not clear when investigators first interviewed Littlefield. But investigators brought him back in on May 5, 1989. This time, they questioned him under hypnosis.

Littlefield mostly gave the same story. He described the small, orange or red four-by-four truck with bright lights on top. But he also said investigators might have better luck talking to a friend of his who’d also been in the boat.

That friend was a guy named Robert Mikula. It took a couple months to track him down, but a Texas Ranger got his statement. Mikula said Littlefield had been drinking that night. And Mikula said, actually, it was around dusk—not midnight—when they saw Shane and Sally on the car.

He did remember the KC lights on the truck that approached them, but, he said, there was nothing “small” about it. He said it was a big truck, painted a dark color.

Now investigators had conflicting accounts from two key witnesses. And Littlefield’s memory might’ve been less reliable because he’d been drinking, but the timing he gave still made the most sense.

A Lake Ranger also came forward who saw Shane’s car at O.C. Fisher Lake around midnight. And there was the Whataburger receipt in the car, stamped at 11:40 p.m. There was also another witness who’d seen Shane’s car earlier at the fireworks show, miles away.

But now there was doubt about the color and the size of that other truck. And David told me, in a case this complex, every clue had to be documented carefully—just having a hunch wouldn’t be good enough to solve the case.

David Jones: They were involved in a fairly large group of kids here. And we were very much inundated with different rumors and different stories. But to take a case to court, you have to have evidence that is substantiated and provable in court.

David said the problems with the early sheriff’s investigation went well beyond record-keeping. Like how they’d recovered Sally’s remains but then left for the day without finding Shane’s.

Karen Jacobs: How did they not see the other body? Were they far apart?

David Jones: They were not together. Actually, I don’t think they did a proper crime scene search at the time.

By the time David spoke with us in 2018, he was the sheriff of Tom Green County. We interviewed him in his spacious, wood-paneled office, with a view overlooking downtown San Angelo.

For all his problems with the early investigation, the case had become his responsibility. It was David who first hired Terry Lowe, in 2013, to investigate cold cases like Shane and Sally’s murders.

Karen Jacobs: And I heard we might be able to shoot some of the evidence. Is that true? You have it here?

David Jones: Lieutenant Lowe will let you see some of the evidence.

From the sheriff’s office, Terry Lowe led us downstairs and down a hallway to a room where evidence from the case was spread over a few tables.

Terry Lowe: Let me get some gloves on.

There were a couple of cardboard banker’s boxes, and piles of manila envelopes and brown paper bags, sealed with red tape.

[Paper bag rustling]

Karen Jacobs: I’ve heard things stay more preserved in paper. Is that—

Terry Lowe: Right. Anything with blood goes in paper because plastic sweats. So these are Shane’s pants.

The pants were tucked into a small rectangle. Terry unfolded them carefully. The fabric was torn and caked with dirt.

Terry Lowe: A lot of the damage to the pants is post-mortem, so scavengers and decomposition.

Terry squinted to read the label on another bag and opened it. Inside was another piece of clothing covered in dirt, small, faded purple, with a polo collar. In his black-gloved hands, Terry held it up by the shoulders.

Terry Lowe: . . . Sally’s T-shirt. So everything’s in fairly bad shape, but I guess after thirty years it’s actually in good shape.

[Paper bag rustling]

I’ll have to come back and seal all this again. This knife actually belonged to Shane and was found at a pawn shop afterwards. The handle was homemade. He made the handle himself. It also went to the lab and nothing, no evidence was developed from it.

Karen Jacobs: Do they know where it was before he passed?

Terry Lowe: Well, he kept it in his car and unfortunately what I don’t have is who pawned it. And of course that pawn shop doesn’t exist anymore. They didn’t keep records like we do nowadays.

New holes develop in this case the longer it goes on. Some things Terry knows investigators collected are just gone. Like the soda cups and straws from Whataburger.

Terry Lowe: That’s the other thing with the evidence is that document A may refer to document B. Document B doesn’t exist. And I mean, after thirty years, actually, we’re lucky to have what we have.

Then there’s the evidence that was never found at all. Things that weren’t found with their bodies, in the Camaro, or in their bedrooms at home. Early on, officers made a list:

First, a brown stuffed animal, about four inches tall, that usually hung from Shane’s rearview mirror. Shane’s black leather wallet was also gone. So was Sally’s purse, which was blue and—the report says—“banana shaped.”

And, although Shane’s boots were found with his remains, there were no shoes with Sally’s. The idea was, if something had been stolen from Shane and Sally, maybe that could help point to the killers.

But so far, those missing items haven’t yielded any answers.

Terry opened another bag and took out Shane’s black leather boots. He pointed to the heel of one boot.

Terry Lowe: When I was first going over this evidence, I found a hair with a follicle right here on the boot, so I got all excited. We sent it to the lab and it came back as a human hair. We got even more excited. Though they sent it for DNA, nothing.

Karen Jacobs: What year was that?

Terry Lowe: Uh, 2016. And we joke with our DNA scientist that you can get DNA from caveman poop, but you can’t get it from Shane’s knife. So, that’s been our luck with DNA. It hadn’t been a positive experience.

Shane and Sally’s clothes had been left outside for so long, Terry said it was nearly impossible to get any DNA from them that might point to a killer—at least with the technology we have today. He hopes that future investigators might be able to learn more from it.

And actually, there is new technology that may be able to help. We’ll talk more about that in a later episode.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): Sheriff David Jones retired in 2020. To replace him, voters in Tom Green County elected a former Texas Ranger, someone who you’ve actually heard from already.

Nick Hanna: Hello, I’m Nick Hanna, Republican candidate for the office of Tom Green County sheriff . . .

Nick Hanna. He’d already spent years investigating Shane and Sally’s murders with the Rangers. Now he runs the office that’s responsible for solving the case.

Nick Hanna: You know, I first came here in 1984, right after I graduated from Plains High School in Plains, Texas. You know, Plains is located in South Texas . . .

Over the years, he worked his way up through the state police, moved away for a time, and came back to San Angelo in 2007 as a Texas Ranger.

He told me he’d been assigned to work on cold cases like this one, but right away he was assigned to an even more high-profile case, the one he’s best known for today.

News reporter: For two days, ex-members of the Fundamentalist LDS church have testified about abuses they suffered at the hands of Warren Jeffs . . .

In April 2008, Nick served as a lead investigator in the raid of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, in Eldorado, about 45 miles south of San Angelo. The FLDS is a wing of the Mormon church that still, illegally, embraces polygamy. And its leader, Warren Jeffs, had been on the run from federal authorities.

Here’s Nick talking about the case on a local broadcast in San Angelo.

Nick Hanna on broadcast: I remember there were some grain elevators on the ranch, and there were some of the members, I remember, climbed up, and they were watching us watch them. And so, it was a little bit of a standoff, a Mormon standoff if you will.

After receiving a tip that children at the ranch were being sexually abused, Texas Rangers and other officials took more than four hundred children into state custody. Courts eventually ruled against the state and reunited the children with their mothers. But several FLDS men were convicted of crimes. Warren Jeffs was sentenced to life in prison for sexual assault.

It was the sort of high-profile case that can define a career for a lawman like Nick Hanna. But once Nick was done, he returned to his stack of cold cases, including the murders of Shane and Sally.

When he first began looking into this case, around fifteen years ago, Nick says he saw a few big challenges—and the initial police work didn’t help.

Nick Hanna: We don’t have a crime scene. We really don’t have DNA. Marshall Stewart, the victim’s father, he was the one that went and actually they had him drive the vehicle from the scene to the sheriff’s office for processing, a practice that today would be abhorrent. And in 1988 I guess I would say maybe it was just against best practices, you would never have someone drive your vehicle down to be processed.

And as far as Nick could tell, there was a gap, right after Shane and Sally disappeared, when the deputies weren’t questioning witnesses.

Nick Hanna: And so I think, for a period of thirty or sixty days, I think a lot of things were left undone. It’s become now a very big obstacle in this investigation. Where a lot of people should have been ran down and talked to, that’s what we have to deal with. Because later we do have, we have some good statements and we have some good leads. But when you lose that initial time and it’s not being proactively investigated, then it’s hard to overcome.

Even the physical evidence is hard to make sense of—like the Stetson hat pin found on Shane’s body. Terry said, based on what he knows about the original investigation, it’s hard to know what to think.

Terry Lowe: You know, we’ve all conjectured that till we’re blue in the face and whether it was an accident or was actually placed there. Without speaking bad of the investigation back in the day, very few protocols were followed, and so we weren’t able to determine if that hat pin had been touched by fifteen police officers.

And then there’s the stolen gun.

Nick Hanna: Sally had provided Mr. Counts with a stolen firearm in the weeks prior to her death. And information—in other words, she was a confidential informant—along with some information about some burglaries that had occurred. Why is that important? She’s engaged in snitching, which will get you killed in the criminal world.

But the early investigation reports don’t seem to make much of this possibility.

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): I put this question to Larry when he and I spoke.

Karen Jacobs: I’ve heard that she was an informant for the police. Is that true?

Larry Counts: If she was, it wasn’t with us, so I don’t know.

In other words, Larry didn’t consider Shane or Sally to be informants just because they showed him around their hangouts. But, since Larry turned over the gun to the city police, he said it’s possible they got in touch with her.

Larry Counts: The police knew who she was, and they may have talked to her about the gun and stuff, and so she may have been an informant for them, but I have no knowledge of it.

Karen Jacobs: ‘Cause what comes to my mind is if . . . well, if she turned in a gun, or was working with the police, and then she goes missing, wouldn’t that be an immediate red flag?

Larry Counts: Sure. Yeah.

For Nick, though, it’s a big problem that Larry had been getting information from Shane and Sally, with so little detail included in the investigators’ notes.

Nick Hanna: And I’m not exactly sure what the relationship was between the deputies and the victim. It’s problematic. This case is problematic.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): So after all of that—about what we don’t know about the case—let’s review what we do know, and what the authorities know. Because, despite all the holes in the case, they still believe it’s one they can solve.

First, we know Shane and Sally were mixed up with a group of kids that they were trying to leave behind. According to Marshall, one of these guys, Steve Schafer, was covered in bruises when Marshall came to ask him about Shane. Someone also gave Sally a gun to get rid of, which left her worried enough to call the cops. And Shane owed money to someone—they’d argued about it on the phone the day he disappeared.

On the night of the Fourth, Shane and Sally were out by the lake around midnight, and two guys in a truck drove up, argued with them, and drove away. And, based on the way Shane and Sally died, investigators are confident there were at least two killers.

There are four men whose names turn up again and again in the case notes, who investigators have interviewed repeatedly, who multiple witnesses said were involved with the crime. All of them were part of the same social circles that included Shane and Sally.

Nick Hanna: So there was kind of a pool of suspects. And these individuals had been involved in some kind of post-incident behavior which really put them on the radar. And the suspects were probably Steve Schafer, John [Gilbreath], Jimmy Burnett. There’s a little Heath and a big Heath, their names just escape me. I should have my notes.

Steve Schafer. You’ve already heard about him. Marshall says he saw him with a bruised face shortly after July Fourth. Some sources told investigators that Schafer was a leader in the occult group. And in the summer of 1988, Schafer drove a truck with KC lights.

Then, Jimmy Burnett. Burnett was seventeen years old that summer, and he’d been a member of the Lost Boys. Actually, Lee Parker told me he thinks Burnett is the one who named the group. One witness said Burnett had a small stash of guns he liked to show off. And Burnett also drove a truck with KC lights.

And then there’s this: according to the investigators’ timeline, Sally had spent a couple of nights at Burnett’s place late in June 1988, a week before Shane got back to town.

Nick also mentioned “Little Heath” and “Big Heath.” Little Heath is not mentioned much in these reports. But Big Heath is Heath Davis, who was eighteen that summer. Davis hung out with Jimmy Burnett, and investigators said he was the head honcho in a local drug distribution ring. Later, Davis would go on to be arrested for drug possession, as well as burglary, robbery, and rape.

And then there was one more suspect, a guy with a habit of inserting himself into the case. Larry Counts told us about him.

Larry Counts: Well, there was one of the people that was a friend of theirs that they ran with, and that guy, like, every week he would come in with a different story.

Karen Jacobs: He would come to the police station?

Larry Counts: Yeah, he would come, or he would call us, and he came up with a different story all the time, and he became one of our suspects, and we’d had him polygraphed, I think either two or three times, by different polygraph people, and they all said that what little he knew about the actual incident was, he was probably told or read about it.

Karen Jacobs: Will you tell us who that is?

Larry Counts: John Gilbreath.

Karen Jacobs: Oh, yeah. And you don’t think that was a—

Larry Counts: No, I don’t think it was him.

Investigators looked into other suspects, but they seemed most focused on these four.

And if they were right that Shane and Sally were killed by more than one person, it might seem surprising that everyone who was involved has kept this secret for so long.

But maybe they haven’t kept the secret at all. Maybe one of the many rumors investigators heard really is the truth. Nick says it’s been impossible to know for sure.

Karen Jacobs: So everything you have is circumstantial, and what is it that you need to solve it? Like, what would be presentable in court?

Nick Hanna: Well, here’s what we need, is we need some . . . We have some witnesses, as you’ve seen. The problem is, you have a number of conflicting witness statements. And as investigators, we can’t select one of the four, the one we like best. And so when we have witness statements, conflicting witness statements from different witnesses placing different individuals at the scene, different individuals pulling the trigger, we’ve got to figure out a way to corroborate somebody’s statement. So what we need is someone in the community with information about the crime that maybe hasn’t come forward or maybe hasn’t talked to police before, to provide us that information.

In fact, those four names are the same ones investigators came up with early on. For all the years of work by Larry Counts, Lou Hargraves, Bill McCloud, David Jones, Terry Lowe, Nick Hanna and all the other investigators who’ve touched this case over 35 years, in some ways, not much has changed. They’re still waiting for someone to come forward with a story they can prove is the truth.

Karen Jacobs (voice-over): By 2018, when I first interviewed these investigators, my crew and I all hoped that we might be there filming when that big break came. Or that someone would see our story on TV and finally come forward.

But that’s not what happened. At the start of the pandemic, our talks with TV distributors fell through. And the Texas Department of Public Safety—who’d let me in to film their work—cut the project loose.

But I still had all my footage, and I was still fixated on the hope that someone might hear from Shane and Sally’s parents, and decide it was finally time to say what happened that night.

Over the last year, Rob and I have gone back to the investigators to hear the latest about their work, and to ask new questions of our own. But the relationship is different now: I met them as a client, hired to help them tell a story. Now, we’re independent reporters. We’re the ones who decide how to tell the story, and what to tell.

Nick and Terry still answer our questions, but there’s a new dynamic.

Nick Hanna: I assume you encouraged the families to write me letters asking us to turn that over to the AG’s office or get the AG’s office involved. Did that happen? Yes or no? I don’t think it’s a coincidence.

Rob D’Amico: Well, it’s a yes and no . . .

Nick Hanna: What’s your end goal for this deal? A good story?

Rob D’Amico: We want to make it a good story because if it’s not a good story, then it’s not going to get much attention.

Karen Jacobs: I mean, the hope is, we originally thought, was get it out in the public, and that’s the beauty of a podcast. You drop them every week and then people start responding and maybe have someone step up, and that would be very helpful.

Rob D’Amico (voice-over): This case has seen years of mistakes by law enforcement, and rumors about everything from stolen murder weapons to satanic rituals.

So, we’ve spent the last year chasing down these leads on our own. Every person I’ve seen mentioned in the investigation, I’ve called them—or I’ve called their brother, or their ex-wife, or ex-roommate, to try and find them.

I’ve filed records requests with the sheriff’s office for more of the case files, but the Texas public records law says agencies can withhold records from an open investigation, even one that’s 35 years old. And that’s what Sheriff Nick Hanna has done. Whose DNA did they test against the evidence? What about the stolen gun? Can we see more information on suspect alibis? In each case, I was told nope, it’s an open investigation.

We do have some records, mostly summaries of who the investigators interviewed, and the basics of what they said. And the sheriff has answered some of our questions. But it’s up to him if he wants to share more.

There are also a few things we’ve heard that investigators have asked us not to mention. Items found by Shane’s Camaro, and details about the remains. Details that only the killers would know, that could help investigators tell whether a witness has real information. In our view, leaving these out won’t mislead you or make the story incomplete.

One thing I’d really like to know more about is that stolen gun. Because if you boil down the facts of this case, I think you have Shane and Sally handing a gun to the police—a gun that was supposedly used in a murder—and three months later, they’re dead.

Larry didn’t remember who he gave the gun to at the police department. The police department told me they couldn’t find any record of this gun. For a while, I wondered if there was anyone but Larry who did remember this gun.

But then we talked to Sally’s friend Diane, who said this:

Diane: I do remember when I went with Sally to Jimmy Burnett’s one time, there was . . . it’s real foggy, and it’s hard for me to remember, but I want to say I remember something about a handgun, and I think that maybe he gave her a handgun, and she asked me, “Should I turn it into the police? What should I do?” And I was like, “I don’t know. I have no idea.”

So Diane remembered the gun, or thought she did. But she said it came from Jimmy Burnett, the guy Sally had stayed with in June.

At first, Nick Hanna and Terry Lowe told us they didn’t know who gave the stolen gun to Sally. But eventually they found a report from Deputy Larry Counts, saying that it was Steve Schafer who gave her the gun.

Terry said he’d looked into the gun himself, but it seemed to be a dead end.

Terry Lowe: Once I started tracking the gun, I found out that the gun was stolen from Cole’s Army Surplus store here in town, and that it was a city case and that Larry Counts had turned the gun over to the city. So I didn’t pursue it any further.

In March 1989, four months after the teens’ bodies were found, an officer was walking down a hallway at the San Angelo police department. He noticed something lying on the floor. As he got closer, he realized what he was looking at.

Randy Swick: I was walking into communications, and I saw her driver’s license laying in the hallway, and I picked it up and it was Sally McNelly’s.

Sally’s driver’s license. Which, up till then, was still missing. And it wasn’t found in the sheriff’s office—which was investigating her murder—but in the city police department.

Rob D’Amico: So what did you do with the license?

Randy Swick: I put it into evidence if I remember right, wrote a report. Did you find my report?

No, I didn’t find the report. Actually, the police department told me the report doesn’t exist.

Yet another key document in this case, just missing.

And remember that theory Larry Counts had, about a leak inside the police department? An officer who was close with the murder suspects? Larry says he’d tried to find out who it could be . . .

Larry Counts: Then another person said that involved in this satanic stuff was a police officer named Randy. So we went back, and we did as much investigation and searches we could. And that Randy Swick is the only police officer with the first name of Randy that we could find in the police department.

And it turns out, the officer who found the license?

Rob D’Amico: Well, first off, tell me a little bit about yourself. If you could just state your name, and who you are and what you do . . .

Randy Swick: Okay. I’m Randy Swick.

That’s next time, on Shane and Sally.