This article appeared in the October 2017 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Coming Storm.”

Just a few nights after Hurricane Harvey dumped more than fifty inches of rain on Harris County, I went to dinner at the home of some friends in my high and dry Houston neighborhood. In what I now see was a preview of coming attractions—the new normal—another guest had just moved his family into an apartment, because his house, in southwest Houston, took in at least a foot of water. He and his wife and twelve-year-old daughter were hanging in, but a lifetime of collected personal possessions was lost forever, and the cost of restoring what was left of their home would be hefty, not just in cash but in emotional turmoil and time lost from work, family, and friends.

Over the comforts of beer and tacos, we all offered sympathy. He shrugged us off, offering what has become one of the tropes of the disaster that began after Harvey made landfall on August 25. “I’m fine, my family is fine,” he said, in an accent that betrayed his origins in New York City, “and that’s all that matters.”

Then he flicked us away with his hands. “No whining,” he said. That’s why he loves Houston, he added. No whiners here.

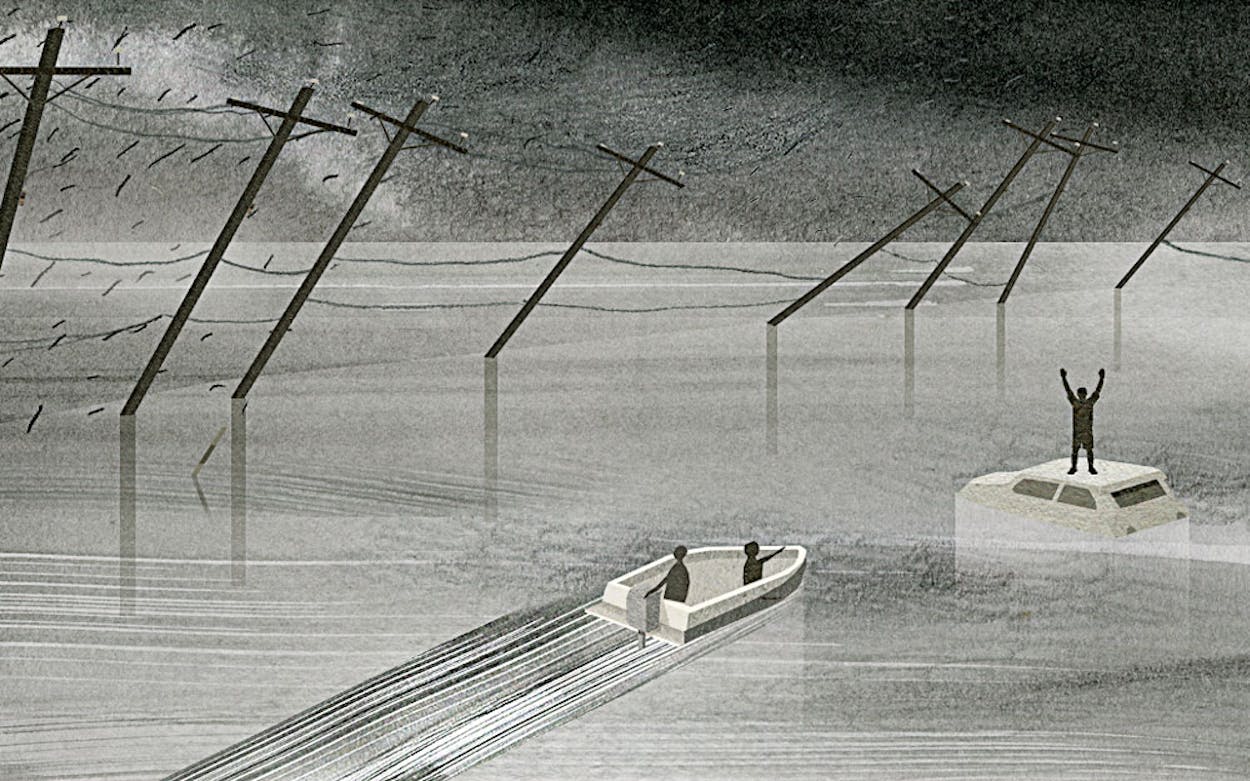

“Congratulations,” someone at the table responded. “You’ve become a Houstonian.” We all laughed the way people do when at least the acute part of a crisis has passed—softly, gently, and sadly in agreement. But I for one knew that those of us who’d made it through the storm unscathed were simply lucky. Lucky because of where we live in town, lucky because Harvey could have been even worse if we had taken a direct hit and lost power and water like so many Houstonians did during Hurricane Ike, in 2008. “Fine,” I am coming to see, is relative. We are all fine. We are going to be fine. People who weren’t helicoptered or boated out of their homes with whatever they had on their backs have been pitching in like crazy, as you have no doubt seen on TV and social media or read in your newspaper if you are over a certain age. Houstonians are scouring their homes for every spare pillow, blanket, bar of soap, and pair of shoes to donate. At the George R. Brown Convention Center, they are walking dogs for evacuees too old or too exhausted to do it themselves. They are forming roving home-repair gangs, tearing out rotted Sheetrock and insulation in water-damaged rooms that stink to high heaven, a mold-related odor that can best be described as a combination of rotting vegetables, ammonia, and sewage.

So yes, we are all in this together. Every resident of Harris County has experienced a near incomprehensible collective loss, and now we have to figure out how to move forward. And yes, forgetting the past and sprinting toward the future is something Houstonians have been great at since, well, this place was founded. But in the wake of the storm, I have come to wonder whether the stories we tell ourselves about this place we love actually serve us anymore or, in fact, whether they contributed to the disaster we’ve just endured, and will endure for years to come.

The average Houstonian’s immediate response to the storm has received straight As from just about everyone on the planet, and rightfully so. People were good-natured, generous, industrious, innovative, and tireless—all terms I use when I talk about why I have made my home here for nearly forty years. Within hours, massive numbers of citizen volunteers had set up a shelter at the convention center. On a smaller scale, but just as essential, there was the West University homemaker who set up a web-based clearinghouse (seemingly in minutes!) connecting those who needed help and those who wanted to help. Houstonians by the hundreds made their homes into donation drop-off and delivery sites and set up ride shares for volunteers headed to evacuee shelters. People got in their cars and set off in all directions, stopping to offer help in neighborhoods many had probably never even heard of before. GoFundMe sites were established for everything from individual families to horses who barely survived the storm. Restaurateurs worked overtime to cook and deliver hot meals to first responders and evacuees. I was particularly happy to see our much-vaunted affection for diversity in full force. People who usually find themselves on different sides of the political aisle were too busy rescuing and being rescued to get into arguments over bathroom access and immigration. On my NextDoor app, a self-described gun lover from my neighborhood tried to stir up trouble by posting a photo of a young black man, his face covered with a bandanna, who bragged that he was about to go loot white neighborhoods. Other posters quickly attacked the message as false, and it vaporized.

All of these heroics, mind you, took place while people were enduring varying degrees of delirium and exhaustion. Even those of us who didn’t lose everything have found that four or so days of unrelenting rain, combined with nonstop televised weather updates (labeled “catastrophic”) and the demonlike howls of cellphone alerts and frightening internet scams, have been both enervating and disorienting. There were tornado warnings, and there were more than a few suggestions that one of two aging dams might collapse and send water cascading into otherwise safe, dry neighborhoods—like mine. A week after the storm, I still have trouble remembering what day it is.

Part of that is because we have all been racing in a zillion directions, but it’s also because we’ve had to adjust to a weird new topography of devastation. Houston suffered a large share of the total cost of the disaster in Texas, which could be as high as $190 billion. The wreckage left in Harvey’s wake will most likely be the costliest disaster in U.S. history. As of September 6, the death toll in Harris County stands at thirty but will probably rise as the waters recede. Our slow-moving, shallow bayous are still, in some places, raging rivers of murky brown water. Getting around is still tough, as flooding continues with the release of water from those two aging dams. (Thanks to Harvey, we’ve all learned the difference between a “controlled release” of water and an “uncontrolled release.”) Memorial Drive, a main thoroughfare from the western suburbs to downtown, was still closed a week after the storm, because of high water. Almost every performing arts venue in the downtown arts district suffered some damage, particularly the famed Alley Theater, which recently celebrated the completion of a $46.5 million renovation. The pristine white walls and scarlet carpet of the theater’s lower level have been soiled by ten feet of slimy, stinking water. To date, state and federal courts remain closed. And don’t get me started on the effects of chemicals from various toxic waste sites seeping into our water and air—we just don’t know the scope of the damage and probably won’t for months to come.

Yet if dirty air and dirty water and flooded, congested streets all sound a little familiar, there’s a reason. As Ginny Goldman, a longtime organizer who is currently chairing the Harvey Community Relief Fund, said to me, “There are often these problems in a city of any size, but here, where we haven’t done enough to deal with affordable housing and transportation access and income inequality, and where the state has blocked public disclosure of hazardous chemicals in neighborhoods, then a natural disaster hits and we pull the curtain back and it’s all on full display.”

Just after Harvey started pounding Houston with what looked to be never-ending rainfall, I got an email from an old friend who was lucky enough to be out of town for the main event. Sanford Criner is an inordinately successful member of Houston’s developer class, a vice chairman of CBRE Group, the largest commercial real estate and investment firm in the world. He is also a native Houstonian, and like so many of us here, he was already thinking about what was coming next. (Yes, it’s a Houston thing.) “Either we are committed to a future in which we collectively work for the good of the whole,” Criner wrote, “or we decide we’re all committed only to our individual success (even perhaps assuming that that will somehow lead to the common good). I think our story now is either: (i) Houston is the new Netherlands, using our technological genius to develop sophisticated answers to the most challenging global problems of the twenty-first century, or (ii) we are the little Dutch boy, who pokes his finger in the dike, solving the problems of the twenty-five people in his neighborhood. How we respond to this will determine into which of those categories we fit and will define Houston’s future.”

“I’m hopeful. But scared,” he added, neatly summing up the stakes moving forward.

In the past few decades, even as Houston was making its mark on the global economy, building gleaming towers designed by world-class architects and mansions the size of Middle Eastern embassies, as we were hosting world premieres of radically new operas and ballets and coming up with those crazy Asian-Cajun fusion dishes to die for—even as we really were and are optimistic, innovative, entrepreneurial, pretty tolerant, and all that other good stuff—we were doing so selectively. That instinct for the quick fix, or no fix at all, has been with us since the city started expanding in the sixties and seventies and is still a part of the Houston way. In reality, we keep dragging our dark side forward, a shadow sewn to our heels with the strongest surgical wire.

So now the question we face is this: Will Houston become a model for flood relief and disaster recovery, or just another once grand city sinking into mediocrity? In other words, can we be true to our reputation for innovation and aim for something higher than the status quo? The answer depends on which aspects of our culture wind up dominating the search for solutions.

Yes, Houston’s can-do spirit saw all those people powering rescue boats and wielding crowbars. But the cockeyed optimism we’re so proud of has something in common with denial: things were good, so why mess with infrastructure improvements and the taxes needed to pay for them? Our two reservoirs should have been repaired long ago, and a third should have been built—a job the county somehow never got around to, assuming, correctly maybe, that taxpayers wouldn’t want to foot the bill.

Yes, Houston got more rain in a few days than it gets in a year. But if we had worked harder at that kind of flood protection, we might have avoided turning our convention center into an evacuee shelter, or talking, as we are now, about turning once vital communities into retention ponds. As for the city: every apartment building that required parking spots for each unit—at least 1.66 spaces for two bedrooms—contributed to the concrete sprawl that helped the flood along. Meanwhile, public transportation— an adequate bus system? A few more lines for our teensy train network?—still remains a topic of debate, as it has since, oh, at least the seventies.

Houstonians are exceptionally proud of our diversity, but how welcoming are we, really, to immigrants and others of modest means? Houston may have jobs, but it’s become increasingly difficult for ordinary people, much less those with fewer resources, to get to work and to find a decent place to live. In recent times, tax breaks have gone to builders of luxury housing downtown, with little to nothing allotted for affordable housing for the rest of the population.

If Katrina exposed New Orleans’s long-simmering racial divide, Harvey has revealed that Houston’s problems have more to do with our age-old devotion to growth at all costs, which comes with handouts for developers and city officials who have looked the other way for decades. I would wager that few people here are willing to say that Houston should stop growing, myself included. But the repercussions of willy-nilly expansion have been laid bare. As more than one civic leader told me, although residents have earned much-deserved praise, the citywide havoc created by Harvey has hurt Houston’s carefully nurtured brand.

Jim Blackburn, an environmental lawyer and co-director of Rice University’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education, and Evacuation From Disasters Center, holds that some of the solutions must come from Austin. “The Texas Legislature has a role here,” he said. “We’ve got to get focused on more serious issues than this past legislative session.” Blackburn, who believes that more destructive storms are going to become a way of life, is a man with many suggestions. In early September, he produced a fifteen-point plan to mitigate the effects of future storms. His ideas included buyout programs for homes in neighborhoods that have been flooded time and again, better mapping of floodplains, updating FEMA’s largely ineffective flood insurance program, preservation of future wetlands, modernizing early warning systems for floods, designing safer subdivisions, and so on.

“Houston is at a turning point,” Blackburn said. “This should not be a deathblow, but if we don’t get our act together, this will result in the beginning of a real economic decline.”

A giant bonanza courtesy of the federal government is supposedly going to help solve some of these problems. How will the $15 billion in starter money, approved by the U.S. House of Representatives on September 6, be used and distributed? How much will political partisanship interfere with progress? Will the money go to the established powers, to lawyers, lobbyists, and the big engineering firms?

Now is a chance to make sure the middle- and lower-income people who have literally built the city—and will have to do it again—get their fair share. The volunteers who pulled Houston together during the immediate crisis will still be needed for even harder work ahead. “Who is going to be first in line?” asked Goldman, the community organizer. “There needs to be an alliance of trusted community organizations ready to be in the thick of these fights about how the federal money is going to be spent.”

There are needed and much-ignored public works projects that haven’t progressed beyond the drawing boards of creative citizens. If the people of Texas don’t want the $15 billion Ike Dike, a proposed storm-surge barrier that would shield the Galveston Bay, a smaller gate at the ship channel entrance could be constructed for $3 billion and provide almost as much protection.

The biggest question, then, is whether the city, state, and country that spawned the space program can devise solutions that protect us from climate threats, arguably the biggest problem facing the world today. With the increasingly warming waters of the Gulf right next door, Houstonians will have to prove that we can protect our residents and our businesses in the most advanced way possible—or else. “The refineries did not get horribly flooded by Harvey,” Blackburn pointed out. A bigger storm with a large surge “would put them out of business for six months to a year and have a huge impact on the region and the U.S. We haven’t seen the big one yet.”

Maybe what Houston, and Texas, needs is an infusion of pessimism, something that isn’t really in our DNA but a quality that might help us plan for a more difficult and complex future. “If any place in the world can pull through, it’s us,” Blackburn said. “But, boy, are we gonna need some leadership on this.”

Whiners need not apply.