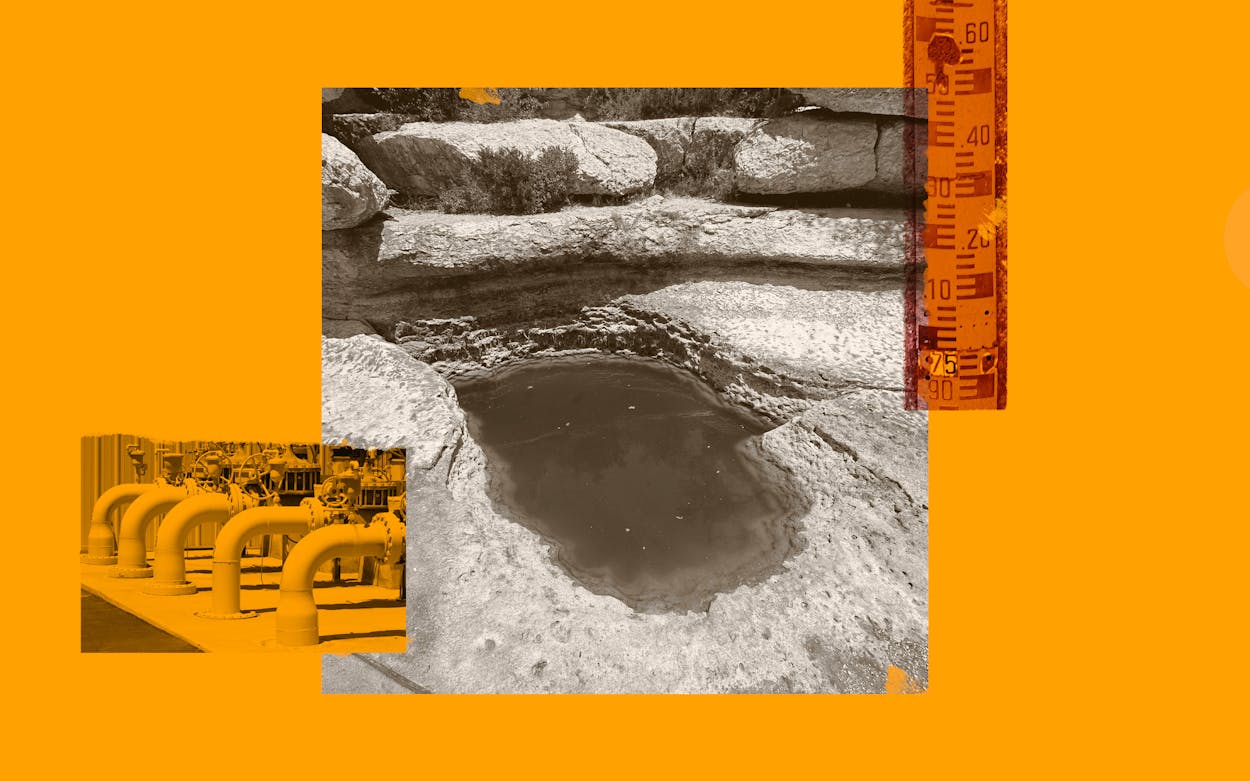

After sitting dry for 222 days, Jacob’s Well, the iconic artesian spring near Wimberley, has started to flow again. From mid-June through mid-January, the popular swimming hole was a miserable sight: the water level had receded below the lip of the well’s mouth, leaving behind bleached limestone and a dead-looking Cypress Creek, usually the very picture of a healthy Hill Country stream. Hays County, which manages the spring as a park, banned swimming. Today, thanks to beneficial rainfall, the spring is gushing forth again from the Trinity Aquifer, the much-stressed groundwater source underlying much of the Hill Country.

“I teared up when I went down there,” said David Baker, an artist and conservationist who runs the Wimberley Valley Watershed Association. “There were all these kids, local kids who were coming up with smiles on their faces, and it was a celebration.”

The return of Jacob’s Well is welcome news. But it’s likely to be only a temporary respite. Once a perennial spring that kept flowing even during extreme droughts, Jacob’s Well has been drying up with increasing frequency over the last two decades thanks to drought and overpumping. Its new intermittency is a warning sign that the Trinity Aquifer is diminishing rapidly. Untrammeled population growth in the Hill Country, particularly along the Interstate 35 corridor, is posing an existential threat to natural treasures in the area, and to the water supply for thousands of Texans flocking to the region’s cedar-choked hills and clear-flowing streams.

Back in August, I wrote about Jacob’s Well, my old stomping grounds of Hays County—where the population has doubled in the last twenty years—and the dilemma of balancing relentless growth with preservation. At the time, conservationists and scientists told me they believed the spring would at least be trickling if a single water provider, Aqua Texas, were to stop extracting more water from the aquifer than allowed by its permit. Aqua Texas, a subsidiary of the utility giant Essential Utilities, had pumped almost twice its legal limit in 2022. As a result, the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District proposed $448,710 in penalties. The company countered with an offer of $0, sending the two parties into negotiations. Aqua Texas simultaneously pledged to pressure its three thousand customers in Hays County to conserve more and “to reduce reliance on water used within the Jacob’s Well Groundwater Management Zone,” where severe pumping restrictions of up to 40 percent are imposed during drought.

Instead, the company has continued overpumping. New data analyzed by Texas Monthly shows that Aqua Texas continues to pump far more water from the Jacob’s Well management zone than allowed by the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District. In 2023, it overpumped by almost as much as it had in 2022, extracting 156 million gallons from two of its wellsites near Jacob’s Well, even though it was only authorized to pump 90 million. In all, the company pumped about 66.4 million gallons beyond its limit, or 74 percent more than its cap. (In 2022, it overpumped by 72.1 million gallons.)

Aqua Texas’s effort to pressure its customers to conserve does seem to have had some effect. The company’s pumping in the management zone was down in the last half of 2023, compared to July through December of 2022. But that’s only a relative improvement. By August, the utility had already blown past its allotment for two of its wellsites. It went on to pump nearly 60 million additional gallons.

The district and Aqua still haven’t reached a settlement over the 2022 penalties, and Aqua Texas is currently operating without a permit, opening itself up to additional fines of as much as $10,000 a day. Late last month the company filed a federal lawsuit alleging that local groundwater regulators had shown “animosity and bias against Aqua Texas” and asking a judge to keep its permit in place and set aside the penalties. Aqua also argues that the district is unlawfully preventing it from shifting its pumping to a site outside the sensitive Jacob’s Well zone (more on that later).

Aqua Texas acknowledged that it overpumped in 2023, but its attorneys say the demand merely reflected the needs of a growing community. “Population in the Wimberley Valley has nearly doubled in the last 20 years, and water permits have not increased to match the new demand,” said Paul Terrill, an attorney representing Aqua Texas, in a written statement. “More residents equal more water usage. It’s not that our customers refuse to conserve, there’s more people in Wimberley Valley than ever before and they need water.”

Baker says Aqua Texas has known for twenty years that its pumping was hurting Jacob’s Well but never fixed the problem. “We can’t have rogue utilities that won’t follow the state’s rules, the State of Texas drought contingency rules, or the local groundwater district rules,” Baker said. “Where would that leave us if we had other utilities that behaved this way? It’s certainly not sustainable, but I also don’t think it’s ethical for a company to take the attitude that they don’t have to follow state or local rules.”

Terrill, the Aqua Texas attorney, countered that it is the groundwater district that is rogue. “They have refused to follow the law—and that refusal has harmed Jacob’s Well and Aqua Texas,” he said. In its federal lawsuit, Aqua claims that regulators have prevented the utility from using new wellsites just outside the Jacob’s Well management zone due to the groundwater district’s moratorium on new drilling. But Greg Ellis, an attorney for the district, said the company has never asked for a waiver. And Charlie Flatten, the general manager of the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District, said more analysis needs to be done to ensure that the new wells won’t harm Jacob’s Well or private groundwater wells.

Flatten said Aqua Texas could come into compliance by fixing leaky pipes—some 30 percent of all the water it withdraws from the Trinity Aquifer is lost to leaks—and aggressively pressuring its customers to cut back on outdoor irrigation. “There’s not very much urgency on their part to do any of those things,” he said of Aqua Texas.“I’m really at this point beyond words with this reluctance to abide by the permit.”

Groundwater, in the words of a landmark Texas Supreme Court case, can seem “occult”—the aquifer’s abundance and its movements are hidden beneath the surface. But Jacob’s Well is quite literally a portal into the aquifer; Baker has long described it as the “canary in the coal mine”—a direct indicator of the health of a complex aquifer that sustains the region’s springs and streams. It cannot be ignored. And with increasing frequency, the well is telling us that things are not okay. Groundwater in much of the Hill Country, particularly the eastern fringe, is seriously overcommitted. The canary, Baker says, is “choking.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Water

- Wimberley