This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Everyone in Nashville knows something is going on with country music down in Texas,” Dan Wentworth says, “and it ain’t in Austin. It’s Beaumont.” If anyone knows Beaumont and country music, it’s Wentworth, the burly, bearded 48-year-old owner of the honky-tonk Cutters. Austin may get the hype, but Cutters is where the new Texas country stars are born.

The tip-off that this 10,000-square-foot club, housed in a plain prefab steel building on College Street, is not just another run-of-the-mill country music dance joint is two hand-painted signs out front by the crushed-rock parking lot. One reads “Cutters—Home of Mark Chesnutt and the New South Band.” The other says “Home of Tracy Byrd and Heartbroke.”

Neither Chesnutt nor Byrd, however, have played Cutters in a while. Both have gone on to larger stardom. But as the signs indicate, they earned their spurs at the club by leading the house band for several years before being discovered. Tonight George Dearborne, with the current house band, Branded, backing him up, provides the music, just as he has for three sets a night, four nights a week, over the past eighteen months—in hopes that the Cutters stage will be his launching pad to Nashville, just as it was for his compadres Chesnutt and Byrd.

If any one establishment defines the Texas honky-tonk for this decade, it is Cutters. Its reputation is based not on its size or any creature comforts but on the talent that has been presented on its stage since the club opened seven years ago. And word is spreading fast: Music fans from across the country are showing up to check the place out. (One morning Dan Wentworth arrived at work to find a trucker from West Virginia standing next to his rig in the parking lot, taking pictures of the club for the folks back home.)

In the late seventies Gilley’s in Pasadena not only brought respectability to the concept of the Texas honky-tonk but it also made honky-tonks downright chic—with a little help from an article in Esquire magazine, a movie called Urban Cowboy, and an amusement device known as the mechanical bull. In the eighties Billy Bob’s in the Stockyards of Fort Worth expounded upon the same theme, promoting itself as the biggest honky-tonk in the world.

Cutters has little in common with either Gilley’s or Billy Bob’s. The decor is standard Texas honky-tonk: a three-cornered bar, bright neon signs and flashy banners hanging from pale blue cinder block walls, and televisions showing sports and the Nashville Network. The poolroom is in the back, and off to one side of the club, two tables for blackjack are set up with house dealers. Most of the action at Cutters swirls around the keyhole-shaped, blond-pine dance floor, where dancers promenade in a smooth counterclockwise flow underneath a mirrored ball. An older couple, in traditional Western wear, dance in a tight clench, their boots scooting along in a blur. Next to them a younger couple in T-shirts, shorts, and tennis shoes somehow manage to make their rubber soles slide in effortless synchronicity. These days country dancing transcends age, class, and other traditional boundaries. It’s not uncommon to hear Michael Bolton, AC/DC, Whitney Houston, or Run-D.M.C. played on Cutters’ sound system. On one of the few occasions when the crowd takes to line dancing, a fad that never much caught on in Southeast Texas, it is to the music of the risqué rhythm and blues ditty “Strokin’,” by soul singer Clarence Carter.

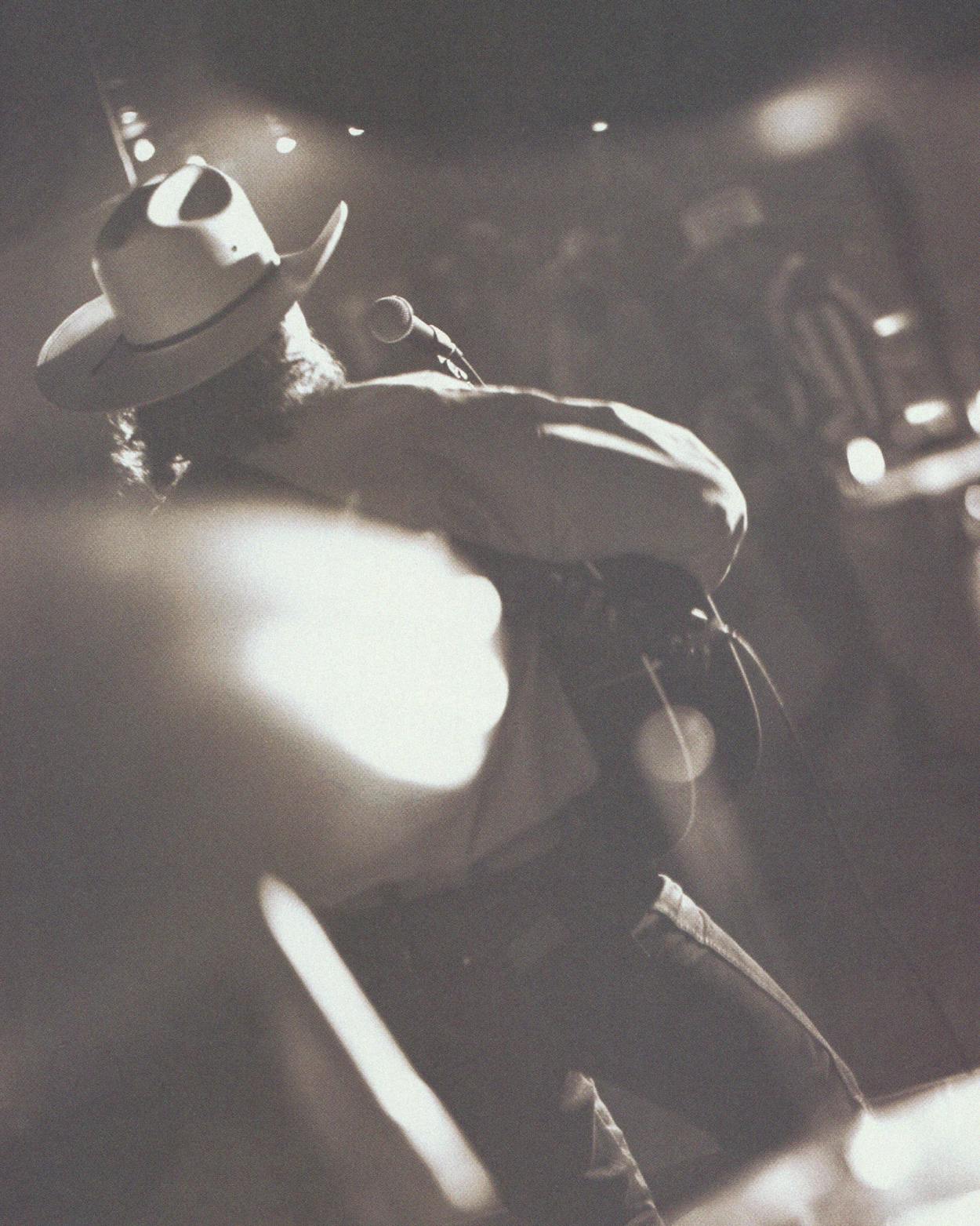

At the end of the dance floor, perched on the three-foot stage, George Dearborne and Branded are doing their best to keep the two-steppers moving. A broad-shouldered Cajun with a beak nose and a mane of permed curls flowing from under the back of his white straw Resistol, Dearborne clutches a burnished cherry-red acoustic guitar and leads the band through versions of time-honored Texas dance hall classics: Faron Young’s “Wine Me Up,” Mel Tillis’ “Heart Over Mind,” Webb Pierce’s “There Stands the Glass,” and Johnny Bush’s “Green Snakes on the Ceiling (One Fool on a Stool).” He mixes the oldies with current hits by Dwight Yoakam, George Strait, and even Mark Chesnutt, whom Dearborne nails cold in his telling of “Postpone the Pain.” Every once in a while, he slips in an original song.

For Dearborne, Cutters is a finishing school. His stage presence still lacks polish, his patter is nothing more than perfunctory, and his singing can be inconsistent, as he occasionally loses control of his vibrato or his voice cracks trying to stretch out a phrase. During a break, he blames his tentative delivery on having too much fun the night before, hanging out and jamming until dawn with some of Mark Chesnutt’s band members at the Holiday Inn. “When the crowd left, we just shut the door and kept on playing,” he says.

But these are minor deficits that will no doubt be smoothed over in time. Dearborne is not just another singing cowboy in another cowboy cover band. He proves it when he sucks in his gut and pours out his soul interpreting “These Arms of Mine,” a ballad written and performed by Dearborne’s idol, Otis Redding. His phrasing is so pure and heartfelt that a listener can’t help but hope that Nashville will soon come calling.

George Dearborne is certainly primed to answer the call. At 34, he bucks the stereotype of what the young country audience is buying, though he prefers to see his relative maturity as a positive asset. “Age I’m at now, I’ve got all my wild running around out of my system,” he says. Although Dearborne grew up emulating Otis while other kids were doing Elvis, the native of rural Fannett embraced country as a 16-year-old, when he started riding bulls in rodeos and discovered the music of Chris LeDoux, the singing bronc rider. “I know what I want to do now. I want to be one of the top country acts out there,” Dearborne says. He even quit his $50,000-a-year job at a refinery so he could put all his energy into honing his act while waiting for a deal to go down. “Cutters has got the honky-tonk atmosphere, all right,” Dearborne says. “It’s a great place to play. The crowd here is very hard to please, but they’re very open-minded. I’m not straight-ahead country. I like country blues too.” His current employer, Dan Wentworth, figures he’ll be able to hold on to Dearborne for another six months at the most.

It remains to be seen whether Dearborne will join the Boys From Beaumont—Chesnutt, Byrd, and Clay Walker, who played Cutters a few times—young male vocalists who have been singled out for bringing back the hard-core sound to mainstream country music. But at the very least, he has a fighting chance. “It’s like deer hunting,” Dearborne says. “You’ve got to be at the right place at the right time to get the big one. I know what it takes to get there because of playing Cutters.”

For all the credit due Cutters, there are many reasons why Chesnutt, Byrd, and Walker have become such phenomenal successes. They all possess great singing voices. They have benefited from the support of Texas’ country music radio stations. They are products of the region’s blue-collar heritage—Tracy Byrd’s father still punches the clock at the Du Pont plant in Orange—which is built upon the same values that are the foundation of country music. One longtime record producer swears it’s the availability of crawfish and cajun coffee and the proximity of southwest Louisiana, where the local folks really do dance all night long.

George Jones is certainly a factor. “You can’t grow up here and not have Jones rub off on you,” says Byrd, one of the disciples who has mastered the Jones method of flaunting one’s twang instead of covering it up. But you could also credit just about any kind of music indigenous to the Golden Triangle, disparate flavors that blend together into a rich gumbo like nowhere else on earth. Take Beaumont’s Moon Mullican, who perfected the pumping, pounding method of piano playing long before Jerry Lee Lewis and wrote the classic “Jambalaya.” Or Corsicana’s Lefty Frizzell, whose lengthy residency at Neva’s Club in Beaumont directly rubbed off on Jones. Or J. P. Richardson, a.k.a. the Big Bopper, of Sabine Pass, who translated his disc jockey patter on KTRM into the number one rap hit of the fifties, “Chantilly Lace,” and went on to write the lyrics for fellow East Texan Johnny Preston’s 1960 million-seller “Running Bear.” The Beaumont–Port Arthur–Orange region is rife with other such legends and semi-legends: cajun and swing fiddlers Cliff Bruner, Link Davis, and Harry Choates; rock and rollers such as Johnny and Edgar Winter and Janis Joplin; crooner Ivory Joe Hunter, the composer and performer of what is still perhaps the most enduring slow dance in the history of the jukebox, “Since I Met You Baby”; Barbara (“You’ll Lose a Good Thing”) Lynn, one of the world’s greatest blues guitarists; purveyors of swamp pop such as Jivin’ Gene Bourgeois, Big Sambo and the House Wreckers, and Clarence “Bon Ton” Garlow; and exotic house rockers like Clifton Chenier, who accompanied his accordion-spiced rhythms with French lyrics, and the Boogie Kings, the quintessential white-boy rhythm and blues show band that regularly worked the Big Oaks Club across the Sabine in Vinton, Louisiana, where the legal minimum drinking age was always eighteen.

Many of those East Texas influences rubbed off on Mark Chesnutt, a young baritone who was discovered in Beaumont by MCA Records in 1988 while fronting the Cutters house band. But when it comes to the number one influence on the current crop of honky-tonk male vocalists breaking out of the Golden Triangle, Chesnutt is not shy about giving credit where credit is due. “It’s me,” he says. No brag, just fact. Chesnutt, the short, stocky thirty-year-old who had been knocking around area clubs since he was a teenager, is the hottest young star out of Beaumont, so big that there’s a billboard on the interstate that reads WELCOME TO BEAUMONT, HOME OF MARK CHESNUTT. His track record includes eleven consecutive Top 10 country singles—among them “Too Cold at Home,” “Blame It on Texas,” “Old Flames Have New Names,” “It Sure Is Monday,” and “Bubba Shot the Jukebox”—spread over three albums that have sold more than two million copies. Having outgrown the honky-tonks and dance halls, he is working his way through small and midsize auditoriums, hoping that his fourth album, What a Way to Live, will take him to the next plateau—the lucrative arena circuit.

As much as he would like to say that his success is because of the abundance of talent living and working in the Golden Triangle and the vibrant live-music tradition found there, Chesnutt has learned enough about how people operate in the business of music to acknowledge the lemming effect. “Nashville wants to find the same thing as me, so they just keep coming back here. They’re just trying to copy the success I’ve had,” he says.

If Chesnutt sounds like he has a chip on his shoulder, he can be excused. He is spending one of his rare days off the road standing around the thickly vegetated back yard of photographer Keith Carter’s studio and home in downtown Beaumont, trying to look photogenic for his next album cover, the forthcoming souvenir tour program, and assorted promotional photos. Try as he might, Chesnutt mostly broods and glares his way through this obligatory ordeal that requires him to stand around, change clothes, squint into the lights, put on more makeup, grin, grimace, and stand around some more.

At least Carter, a fellow East Texan, understands his subject. “Think happier thoughts,” he gently urges Chesnutt between shots, trying to coax a smile out of his surly subject, before he corrects himself. “Wait a minute. That was a dumb thing to say. Think about getting your truck out of the lake.”

In spite of himself, Chesnutt chuckles softly. He’ll endure about seventy film rolls’ worth of coaxing from Carter before he can retreat back to his sixty-acre spread in the Big Thicket near Jasper to find some peace of mind communing with his wife, Tracie, and the bass in his stock tank. “No one bothers me there. I know just about everybody in town, and they know me,” Chesnutt observes. “It’s the one place I can do what I want—hunt, fish, shoot off my guns.”

The Cutters phenomenon comes up between changes of Roper shirts, Levi’s, and a variety of hats. “It’s a dive,” Chesnutt states flatly, a little defensive about the celebrity that has been bestowed on the venue at the expense of his own talent. “Some people think it’s the place, that all you have to do is play there and you’ll be a star. But I just happened to be playing there when the record people came around. I’ve worked all around here for ten years at just about every club that would have me,” he says, rattling off the names of a dozen joints, most of them closed. “People came out to see me wherever I worked. I’d do two nights a week at the Boulevard with just a guitar and packed the house.

“There’s no shortcut to the big time. Ain’t no luck involved. It’s all hard work, talent, and after that, having good management, someone who can put you in touch with the right people. This stuff just don’t fall together. Everyone thinks there is magic in the air. Bullshit—it’s work.”

For Chesnutt, that meant being pushed by his late father, Bob, who knocked around the local circuit himself as a singer, and dropping out of South Park High School at fifteen. Chesnutt had already been playing professionally as a rock drummer and was known for his killer Elvis impersonations when he decided to pursue a career as a country singer. “I wanted to be a star. Hell, everyone wants to be a star,” he says. Chesnutt paid a price for the effort. “I missed out on a lot of things that kids did,” he says, “trying to stay focused.”

The lifestyle did have its advantages, such as attention from ladies and getting to open shows at Jones Country, the ill-fated music park up in Colmesneil that George Jones launched back in the mid-eighties. But with fame came some cold shots of reality. Jones, for example, proved to be an idol with frailties. “George was still drinking, and boy, could he throw a fit,” Chesnutt recalls. Nevertheless, it was the start of a longterm relationship between the two singers; last year Chesnutt won a Country Music Association award for his contribution to Jones’s all-star recording of “Don’t Need No Rocking Chair.”

During a midday break from the photo shoot, Chesnutt lightens up. “I don’t want to have to do stuff like this, but I have to,” he allows, while picking at a plate of shrimp pasta. Has it all been worth it? He pauses a moment to ponder the question. “Sometimes it is. Sometimes it isn’t,” he says. “The only time I feel like I’m a star is when I’m onstage, with all the lights in my eyes and all the people yelling. It’s the rest of the day that’s a hassle.”

Of course, he wouldn’t have it any other way. “I want to be doing this when I’m sixty-three,” he declares, “but because I want to do it, not because I have to, like it is with George, who has got so many bills to pay.” As for the future of the kind of honky-tonk music he plays, Mark Chesnutt feels it is secure. “As long as there are people like me who were brought up on that kind of music, as long as we’re out singing it, everything’s gonna be all right. Hell, yeah, it’s gonna be just fine,” he says.

“C’mon, Bono,” Keith Carter says, summoning Chesnutt back to work by referring to Chesnutt’s resemblance to the lead singer of the Irish supergroup U2. “This time give me that catch-a-bass look.” Chesnutt cracks a smile.

When Chesnutt left Cutters after signing with MCA, he was succeeded by a tall, lanky Vidor boy with teen-idol good looks and eyelashes a foot long. Tracy Byrd’s appearance is so striking that it is a pleasant surprise to discover that he has as much musical depth as Chesnutt. His influences go back to Western swing and old-style honky-tonk music, which he mixes into his live performances. Sometimes during a show he gets what he calls a Hag attack, a spontaneous urge to throw away the set list and sing Merle Haggard songs.

Hag attacks are old news to the crowd at Cutters, where Byrd spent three years leading the house band before his self-titled debut album was released last year. That album immediately established Byrd as a star, producing an impressive string of Top 20 singles—“That’s the Thing About a Memory,” “Someone to Give My Love to,” “Why Don’t That Telephone Ring,” and the number one hit “Holdin’ Heaven.” His latest chart success is the corny and eminently hummable “Lifestyles of the Not So Rich and Famous” (“They wanna see my Fairlane up on blocks/Holes in all our socks”), the single from his second album, No Ordinary Man. Between albums, the engaging 27-year-old managed to squeeze in a bit role as a singing cowboy, warbling “Back in the Saddle Again” in the upcoming George Lucas movie Radioland Murders. “But I’m a singer first and foremost; acting will always be just a sideline,” he swears. A Western swing singer, at that. “I care more about what Red Steagall thinks about what I’m doing than some industry person,” he says, referring to the master of swing, who lives near Fort Worth.

Byrd came to embrace tradition in a roundabout way. His father had an extensive collection of swing 78’s. But he didn’t take to traditional country music until he started attending classes at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos in 1985, where he was introduced to the music of a local hero named George Strait. “Haggard, Strait, and Ray Benson of Asleep at the Wheel—that’s why I became who I am,” he maintains. Yet Byrd is no traditionalist: “To be successful, you’ve got to be current.” In that respect, he says, all the Beaumont boys share the ability to “take a song that’s considered pop and put our country voices on it to make it sound country—in a way, that’s what Western swing was all about.”

He returned home to finish his education at Lamar University, and he played guitar and sang at parties, clubs, and even at Jones Country. College was put on hold when Byrd won a talent contest at Cutters and Wentworth gave him the opportunity to follow Chesnutt. Then Byrd too signed with MCA. Now he plans to follow in Chesnutt’s steps one more time. He’s looking at acreage in the Big Thicket near Jasper, somewhere in Mark Chesnutt’s neck of the woods. But unlike Chesnutt, Byrd genuinely enjoys the wild ride he’s on. He’s happy to be a star. His only complaint: “I don’t have much time to get in a round of golf anymore.”

The third star to break out of Beaumont, Clay Walker, played Cutters a few times but was discovered at the Neon Armadillo, where James Stroud, Clint Black’s producer and the president of the Nashville division of Giant Records, first heard him in the fall of 1992. Though Walker has spoken reverently of George Jones and professes a strong admiration for Merle Haggard, the 24-year-old is the least tradition-bound of the bunch: He also cites Boston and Lionel Richie as seminal influences.

But it’s Walker’s boyish good looks, repeatedly flashed on Country Music Television and the Nashville Network, that provided the extra juice to vault his debut single, “What’s It to You,” to the number one position on the country music charts last year. The follow-up single, “Live Until I Die,” also went to number one. His current single, “Dreamin’ With My Eyes Open,” has reached number 35. His self-titled debut album, released in Agust 1993, will soon go platinum.

Walker may look like a pretty boy, but he actually composes much of his own material (unlike Chesnutt and Byrd, who depend on outside composers for their songs). He writes country pop songs that focus mainly on the details of relationships rather than the usual honky-tonk tales of woe and excess. Walker has also developed a keen eye for business. The son of a welder, Walker realized he had a future in show business when he performed at a talent show at his high school and got a standing ovation. At eighteen, he went to work at the local Goodyear plant to earn enough cash to buy equipment for his band. He handled his own bookings and accounting while playing the club circuit in Texas and surrounding states and in Canada for seven years before finally cutting a record deal.

Along the way, Walker has evidently developed a star-size ego. He declined to be interviewed for this story because it also involved the careers of Chesnutt and Byrd. (“He always was something of a rebel,” recalls Cutters’ Dan Wentworth.) Walker’s publicist said Walker would be happy to cooperate, however, if he was the only subject of the story.

The table at Cutters where Mark Chesnutt and Tracy Byrd signed their deals with MCA Records is now ensconced in the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville. Country pickers and singers from Houston and all over Texas regularly pester Dan Wentworth for gigs, thinking that maybe some of that Cutters magic is all that’s keeping them from the big time. And a steady trickle of fans from faraway places such as Canada, Britain, and Argentina have made the pilgrimage to the little honky-tonk where hitmakers are made.

“I’ve got two outta here,” says Dan Wentworth. “I’d like to see three.” If George Dearborne can’t make lightning strike a third time, others are waiting in the wings. There is Chuck Britton, an engaging 22-year-old who addresses strangers as “sir” and “ma’am.” Britton claims Clay Walker as a cousin and considers George Jones and Eric Clapton his major influences. And there is Marla McCord, a statuesque blonde from North Texas, whose music Wentworth describes as “wholesome and bluesy.” McCord sings not only George Jones songs but also Patsy Cline and Wynonna Judd with equal gusto.

Everyone, it seems, wants to hop on the honky-tonk bandwagon. Garth Brooks, the biggest star of modern country, recently enjoyed a nice ride up the charts with his pseudo honky-tonk hit, “American Honky-Tonk Bar Association.” George Strait stormed back onto the radio with his revision of the George Jones tune “Love Bug.” And Jones himself is once again venerated in Nashville.

But long after the trend runs its course and the last talent scout has left Beaumont, they’ll still be playing pure country, because in East Texas honky-tonk comes naturally.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Beaumont