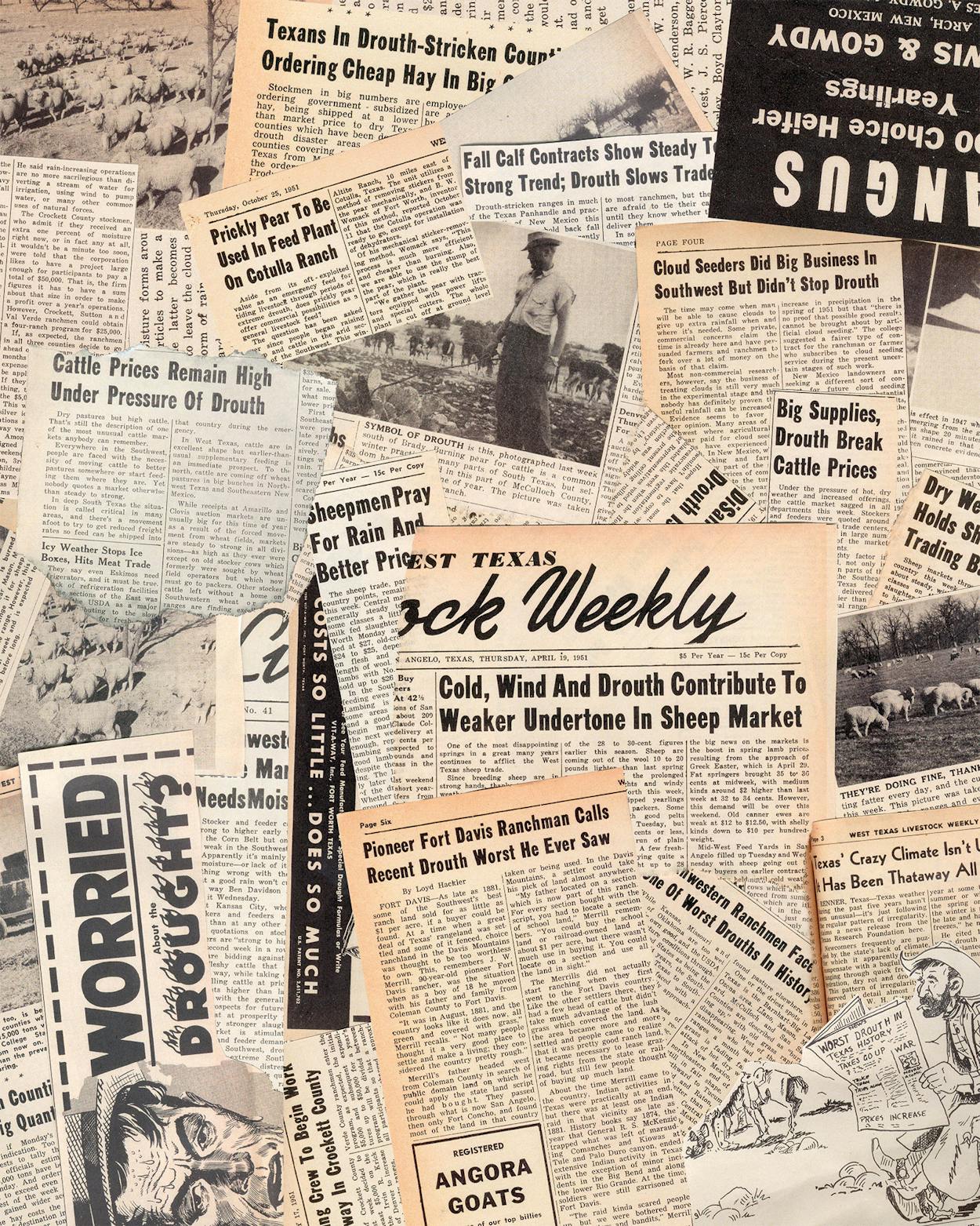

Texans expect drought. It is our curse of geography and climatology to live in a zone where, as the historian Walter Prescott Webb wrote in 1953, “humidity and aridity are constantly at war.” During every decade of the twentieth century, some part of the state endured a serious drought. In 1917, which before 2011 was the driest year on record, an average of just fifteen inches of rain fell across the state. (During a normal year, an average of around thirty inches falls.) During the thirties, soil devoid of moisture turned to dust, rose in fearsome clouds, and blotted out the sun across the High Plains. But the drought that changed Texas forever occurred from 1950 to 1957, when severely deficient rainfall plunged the entire state into an agonizing water shortage. Crops shriveled, creeks turned to sand, thirsty cattle bawled, and reservoirs and wells dried up. When the water finally returned, the state had been irrevocably scarred.

Flying from Houston to Lubbock today, you can see out the window how the dry spell of the fifties shaped the landscape. Reservoirs cling to the outskirts of cities, while many of the tiny towns are in various stages of withering away. The drought triggered these alterations. Between 1950 and 1970, the number of reservoirs in Texas more than doubled; from 1950 to 1960, the number of farms and ranches shrank from 345,000 to 247,000, and the state’s rural people declined from more than a third of the population to a quarter.

Dallas was the hardest-hit major city. Its reservoirs got so low that water had to be pumped down from the Red River, whose high salt content fouled pipes, choked landscape plants, and threatened kidney patients. The relentless heat wave killed penguins at the Marsalis Zoo and compelled the groundskeepers at the Cotton Bowl to drill a water well in the end zone to keep the turf alive.

In the rural areas the suffering was akin to a biblical plague. True to form, the farmers and ranchers confronted their predicament with resourcefulness and grim humor. “The Lord is a pretty good feller,” goes one old joke, recorded in Rana Williamson’s When the Catfish Had Ticks, a collection of drought humor. “But he don’t know a damn thing about farming.” The economics were brutal: rising expenses for feed coupled with plunging market prices at the sale barn. The environmental cost was equally painful: without new grass growth, cattlemen overgrazed their pastures, which damaged the land and made it more susceptible to mesquite and cedar intrusion. Every day, men and women watched the sky for clouds. The sight of just one, drifting in from the horizon, would trigger anxious debates about whether it carried rain or was just an “empty.” If they could afford to, ranchers shipped their cattle to green pastures out of state; if they couldn’t, they stayed put and did whatever they could to keep the animals alive until the rains came. Eventually, the U.S. government stepped in, delivering emergency feed supplies to these cantankerously independent ranchers on a scale that even surpassed the federal intervention of the New Deal period.

Some ranchers with no debt and enough money in the bank were able to hold out until the rains resumed. Others cashed in their livestock and moved to town, never to return to ranch life. The quiet rural-to-urban migration that began with the drought of the fifties continues in Texas to this day.

Though every region of the state suffered through that dry spell, West Texas, long accustomed to the cruelties of climate, had it worst, and San Angelo was the epicenter. This was where President Dwight D. Eisenhower visited in 1957 to inspect the effects of the drought—coincidentally, just before it ended. It was also the home of the late Elmer Kelton, renowned western novelist and ag journalist, whose novel The Time It Never Rained is still regarded as the best account of those dry years. As that book starts, “it crept out of Mexico, touching first along the brackish Pecos and spreading then in all directions, a cancerous blight burning a scar upon the land.”

LISTEN to a radio segment by John Burnett produced by KUT News and StateImpact Texas:

I. The Drout Begins

It is impossible to pinpoint the exact moment a drought commences. In some parts of West Texas, the dry period began in the late forties; elsewhere, it seemed to start in 1950. But by 1953, there was no mistaking what was under way. More than half the state was 30 inches below normal rainfall, and the statewide average monthly rainfall barely measured three tenths of an inch—the lowest level ever recorded. That summer, Corsicana endured 82 days of temperatures above 100 degrees, peaking at 113. The drought was also gauged in other ways. In 1953 the combined income of Texas farmers fell by one fifth from the previous year, and the price of low-grade beef cattle dropped from 15 to 5 cents a pound. On the Edwards Plateau, where most of the subjects interviewed for this oral history lived during the drought (and where many are still ranching, into their eighth and ninth decades), things went from bad to worse.

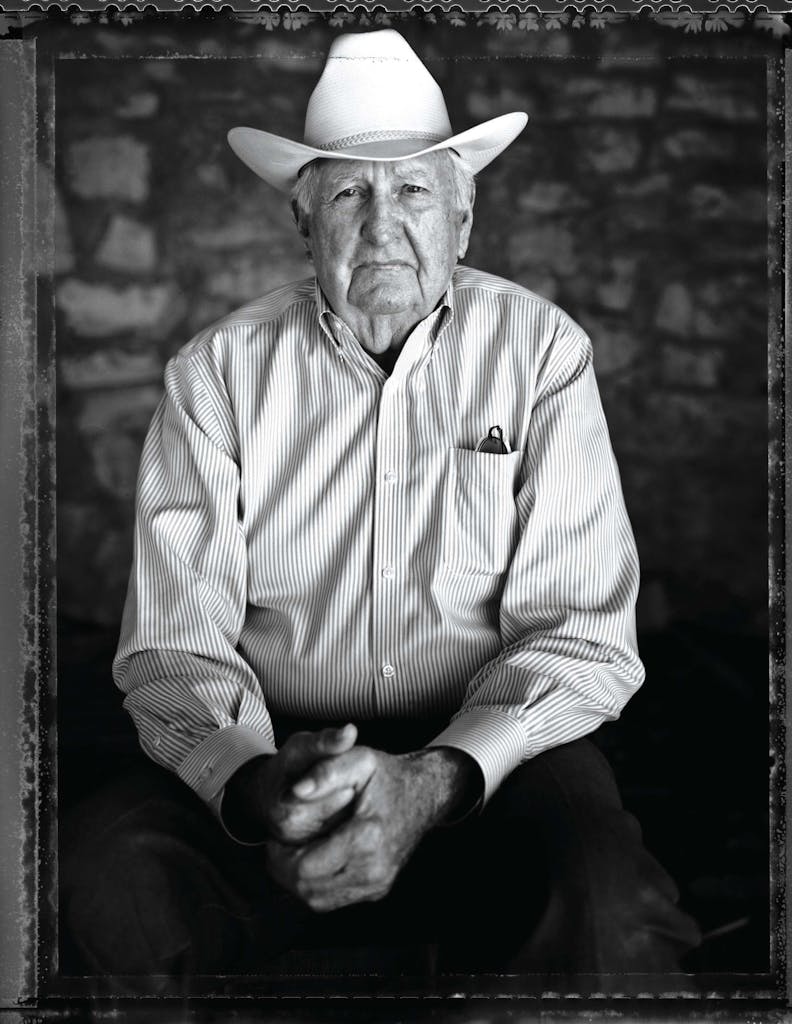

MORT MERTZ, 88, has been ranching in West Texas since 1954. He lives in San Angelo. It started out west. It tended to get dry out there and not rain, and that lack of rainfall just moved east. My dad kept saying, “We have these things; they’ll just go about eighteen months. It’ll break.” But that’s what caught everybody off guard: it didn’t break. It just kept on going, and it lasted about seven years.

SANDY WHITTLEY, 74, grew up in San Angelo and is the executive secretary of the Texas Sheep and Goat Raisers’ Association. The first year it was “Nah, not too bad.” And then it was a little drier the next year. By about the third year, it was beginning to get really interesting, and then it got really serious. From then on it was just tough.

PRESTON WRIGHT, 90, has been ranching in West Texas since 1948. He lives in Junction. It didn’t start overnight—we just kinda eased into it. And when we got into it, it just stayed for a while.

JOE DAVID ROSS, 76, is a retired veterinarian who opened his practice in 1959, treating ranch animals in the counties spread across the southwest portion of the Edwards Plateau. He lives in Sonora. The fifties drought was the worst in my observation because it lasted so long. In some places it started in 1947, ’49. And it was 1957 before people got enough rain and confidence to start bringing their livestock back.

STANLEY MAYFIELD, 93, is the owner of the Mayfield Ranch in Sutton, Edwards, and Hudspeth counties, where it was so dry that when his son was born in 1956, he called him “Seco” (Spanish for “dry”). When it gets dry, it gets dry. You try to live with it till it rains. And you look every day to see if it’s gonna rain.

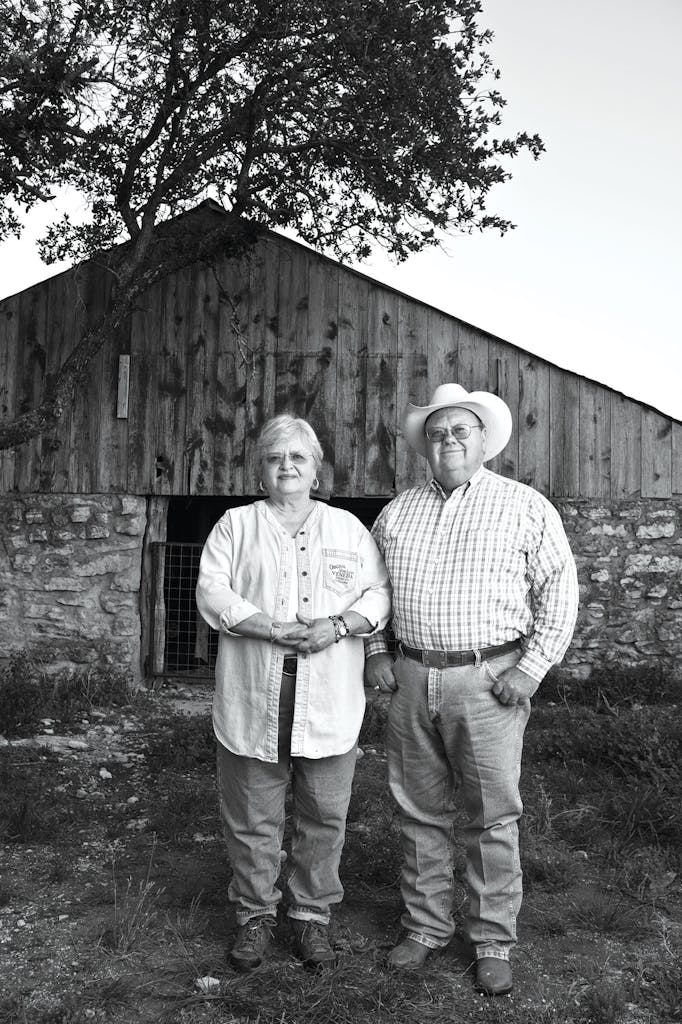

CHARLES HAGOOD, 59, grew up in a ranch family that has had operations in West Texas since the nineteenth century. He has been a banker and rancher in Junction since 1979. I grew up in Junction and then went into the banking business, and I would visit with men that I’d always known as carpenters, painters, merchants. And then visiting with them in deeper detail, I’d find out that they had been ranchers until the drought. Just like my daddy. The drought drove us to town. And that happened all over West Texas—it drove people to town.

MERTZ: I’ve been in business all these years, and I can nearly say that anything that can happen has happened to me. I’ve had hailstorms that killed three hundred lambs. I’ve had lightning kill sixty to seventy sheep at one time. I’ve had lightning kill my saddle horses, my cows. I’ve had bad fires that burned up all my fences. The drought was a hundred times worse.

JOHN HUTCHINSON, 65, is the county attorney of Hansford County. He was raised on a farm south of Spearman. People that irrigated had a rough go of it because they did not have enough water to cover a situation like the drought. The amount of water the sprinkler would put on the field just couldn’t keep up with the temperature, the wind, and the lack of moisture.

NANCY HAGOOD NUNNS, 70, is a rancher and retired accountant who lives in Junction. She is Charles Hagood’s sister. There were no ticks in the fifties. It was just too dry for them.

HAGOOD: When I was a little boy, people would gather and they’d bring their kids over. The men, all they’d talk about was “Is it going to rain?” And if a bunch of clouds were building somewhere, the men would all be out there looking at the clouds and speculating whether or not we were going to get rain. You remember that Randy Travis song about how old men sit and talk about the weather and old women sit and talk about old men? That’s exactly what it was.

WHITTLEY: We’d look outside, and often you’d think, “Oh, that’s a rain cloud. I know that cloud’s got some rain in it,” and you’d smell the rain. And it’d go away. Or you’d hear a little bit of thunder and, “Oh gosh, here it comes,” and it’d go away. It was so disheartening because we needed it so bad, and everybody kept saying, “It’s gonna rain. It always rains. One of these days it’s gonna rain.” Well, after seven years you’re still telling yourself the same old fable: “God won’t let you just die of thirst. I know he won’t.”

II. Survival

As one year turned into the next without appreciable rainfall, West Texas stockmen realized they were in a severe drought, similar to the one their fathers had weathered in the thirties and the one their grandfathers had endured in 1917. It was a grim time. As Elmer Kelton wrote, “There was little about the dry land that made a man feel like talking. There was comfort of sorts simply in the silent sharing of the misery.” Ranchers moved into a mode known as “hangin’ on,” which meant looking anywhere for grass, selling animals when necessary to pay bills, and finding innovative solutions to feed their livestock, such as feeding them prickly pear cactus (after burning the pads to remove the spines) or filling troughs with cheap molasses.

EUGENE “BOOB” KELTON, 80, is an Upton County rancher and the brother of Elmer Kelton. Fifteen dollars was the price for a ton of hay, and [the U.S. Department of Agriculture] was paying half of it. But whenever the government went to pay more, the producers just raised the price of the feed. So we didn’t realize any more help from the government, but the farmers that were growing the feed, they realized a little more profit. That’s kind of the way things go.

ROSS: I was in high school in the early years of the drought. Wasn’t much livestock around. Only thing we had left on the ranch was 1,200 Angora nanny goats. Angora goats are easiest on the land, and since they eat oak and cedar, you could chop the smaller oak trees down, and the goats would eat the leaves.

KELTON: The cattle would weaken down, and then the wild hogs would just start eating ’em while they were alive. They’d be laying there bawling, and those wild hogs’d be eating on ’em. So I fell out with hogs right there.

WRIGHT: Prickly pear is burnt with a pear burner. We used butane instead of propane. You have a hose that comes out of a tank. It shoots a pretty good flame to where you could burn the stickers off the pear. Then the cows would eat the pear. They liked it. ’Course, back then they’d like anything. You weren’t trying to fatten ’em, you were trying to survive.

MERTZ: Oh, man, the cattle get after it. There’s a problem after you burn pear for ’em: they’ll even eat it with the stickers on, and that’s not good. It tears their mouth all to pieces, and it’ll kill a sheep. They get screwworms in their mouth, and then you’d better find ’em and doctor ’em in a day or two, or the worms’ll eat their heads off.

BILL SCHNEEMANN, 77, has been raising cattle in West Texas since 1954. He lives in Big Lake and describes himself as a “semi-tired, wore-out rancher.” We used to feed molasses to the sheep. It was so much cheaper than anything else, and it was a high-energy food. We had a lot of old grass, and that molasses would give the livestock an appetite to go out there and eat that old grass. My brother and I had to fill up barrels out of a five-hundred-barrel tank. You had to build a fire under the molasses because it don’t run very fast in January. So we would fill up some barrels and get that molasses hot and drive around putting it out. The first trough we got to, we leaned the barrel over on its side, and I unscrewed that air bung on top. Well, that barrel had made a lot of gas, and all of a sudden that bung blew out and hit me right between the eyes. All that molasses hit me right in the face. I had to ride in the back of the pickup the rest of the day because my brother didn’t want that molasses all over the truck.

ROSS: In any drought, you don’t want to sell out too soon, and yet you don’t want to abuse the land [through overgrazing]. It’s just a real gamble. What we learned is, you can’t feed your way out of a drought. The way some ranchers got through it was, you’d load up some cattle, sheep, or goats and sell them for whatever a truckload of feed would cost. When you ran out of livestock, you didn’t buy any more feed. People didn’t go into debt as much as they might now.

MERTZ: I don’t believe in running from a drought. I think you’re better off to just sell out and stay there and wait till it does rain again. Basically we sold out of everything until we didn’t have any livestock at all—just some yearling cattle and yearling sheep. There was a line on the highway up to the unloading pens at the Producers Auction, in San Angelo. Good young cows wouldn’t bring but $150. A good young cow now goes for $1,100 to $1,200. But nobody was depressed. We don’t get down.

MAYFIELD: Five years I didn’t grow a sprig of grass. It never rained a drop. But we were a little luckier than a lot of people. We knew a man in San Angelo that had a ranch in South Dakota, and he wanted to pasture some cattle, so we sent a bunch of Hereford heifers up there one year, and they grew so unbelievably that the next year we sent a bunch of cows up there and some sheep too.

KELTON: After you feed a few years and it doesn’t seem like there’s any relief a-comin’, you’ve spent most all your money on feed, so it’s best to sell ’em. And that’s what we did. They were all gone, and you’d just look out there in the pasture and there wasn’t anything. Kind of depressing. It’s kind of like losing your children. It’s just bad. They’re part of the family just like everybody else.

MERTZ: There’s an old saying: Don’t marry your livestock. You want to be ready to part with ’em when it’s time.

III. The Drought in Town

Townsfolk suffered differently than farm and ranch people. Across Texas, at least one thousand communities enforced some type of water restrictions, from limiting lawn watering and car washing to banning the use of evaporative coolers without a recirculating pump. Some towns went bone-dry and had to haul in water by truck or rail. Good drinking water became more valuable than oil. DeSoto put in coin-operated water meters. Meanwhile, cloud seeders and water witchers counted their money.

NUNNS: For Christmas in 1951, my great-aunt gave me a raincoat. It was the color of a green Coke bottle and trimmed in white, buttoned up the front, and had a full circular skirt. It was quite a raincoat, but it was never worn. We referred to it in the family as “the virgin raincoat.” Mother finally let my sister play dress-up with it because it had this wonderful skirt that she could twirl. But it was never worn in the rain. We just outgrew it before it started to rain.

WHITTLEY: We had no outside watering at all. Nobody watered. You had to consider how much water you used to wash the dishes, how much water you used to brush your teeth, how much water you used to wash your clothes. It was so dire that the houses with wells had big signs in their yards that said “Well Water.” Water was in such short supply, and if people thought you were watering outside when you weren’t supposed to be, there was probably going to be a knock on your door. It was a bad time. And it was two shades hotter’n hell.

BOBBY ECKERT, 85, is a CPA in San Angelo. He and his wife, Patsy, were newlyweds and had just bought their first house on South Washington Street when the drought began. We lived on a sloping lot. We’d get a little shower here and there, and there’d be enough water to run down the street, and it stood in front of our house. We’d get the children to scoop up water with pails and throw it on the trees in the yard to give ’em a little drink.

PATSY ECKERT, 80: There wasn’t anything green. There wasn’t much difference between the street and the yard. It was just dirt. It was very depressing to me.

NUNNS: Junction was a rather self-contained community. We really had very little contact with anybody else. We didn’t have television here. We didn’t know what the “in” toy was. We didn’t know what the hot tickets were to whatever concert. Those things just simply didn’t exist for us. I think it was easier for us maybe to be in such dire straits, because you didn’t miss what you never had.

BOBBY MAYO, 81, was the local manager for the H&H movie theater chain in Winters for more than 35 years. I had a friend who was transferred from Odessa to open the drive-in theater here, and he couldn’t ever understand why all these old men would stand in front of the bank down here on the corner. They were looking up at the sky.

WHITTLEY: My daddy was quite a gardener. Our yard was absolutely beautiful. There were gladiolas all along one side, peach trees that probably hated us for making them grow here, a lilac bush. And we lost all of it, every single bit—the grass, everything. My biggest memory of the drought had to do with siphoning the bathwater to save the pecan trees and two rosebushes and one crape myrtle. Those trees are still alive in my yard today, and I’m not above doing it again.

MAYO: We had a little lake north of Winters that nearly dried up. It wasn’t but peter-deep. They had a pump up on Bluff Creek and pumped water here to town. During that drought there was no water pressure—just a trickle. To wash, my mother collected water in the bathtub, heated it, and washed the dishes in the backyard in a big pot. Everybody was doing it.

IV. Calamities

West Texans describe dust storms as bad as or even worse than those of the Dust Bowl years. Men had forgotten the hard-earned lessons of the thirties. High wheat prices and plentiful rains enticed farmers to expand their planting in the years immediately before 1950. But poor soil-conservation practices left the topsoil vulnerable, and when the rains ceased, the wind blew the land into the sky.

TAI KREIDLER, 58, is the assistant director of the Southwest Collection archive at Texas Tech University. They called them the Dirty Thirties. But you know, the name they gave to the fifties was the Filthy Fifties. And that’s for a reason.

EMILY PENDERGRASS, 82, was a young mother living on a farm outside Winters. We would get up in the morning, and you could tell where your head had lain on the pillow. That’s how bad it was.

JOHN SCHWARTZ SR., 74, is a cotton farmer and cattle raiser in Tom Green County. The worst dust storm I remember, it was ’55. I didn’t know it was coming, and I was plowing, and I was to the back side of the field, and when I turned to look to the north I saw it coming and I knew I couldn’t get home. So I got off the tractor and lay down in a furrow that I’d just made. And I’ll never forget it: I had to put my hat over my face to breathe. It was that bad. At that time everybody had chickens and pigeons and guineas and turkeys, and all of ’em were dead. They had to open their mouths to breathe, and the dirt stuck in their mouths, and they all suffocated.

LARRY MCKINNEY, 63, was an aquatic biologist for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department from 1986 to 2008. He lives in Corpus Christi. I was born in 1949 in Big Spring, and I guess I was eight or nine when the drought broke. That was the first time I saw water running in a creek or a river, because they were all dry at that time. I remember playing in sandstorms—that’s what I did. I can still see one today. I was in the first or second grade. The sandstorm that day was so severe that the teacher had us all hold hands, and there was a teacher in the front that led us out to the buses. It was only about one hundred yards from the school building, but they were afraid we would get lost.

SCHNEEMANN: After my wife and I got married, her brother drove home from Texas Tech through a duster in Lamesa. The first thing I noticed was that his license plate was as shiny as could be. It didn’t have any paint left on it. I imagine that was around ’56, ’57.

MERTZ: I’ve never seen jackrabbits like there were during the drought [because they adapted to the dry, overgrazed terrain better than other wildlife]. On these dirt roads there’d be solid jackrabbits. There wasn’t a place for another rabbit to lie down for a ten-mile stretch.

MAYO: The farmers had their guns, and they would walk in lines across certain fields and kill the rabbits in front of them. They’d cover acres and acres, and then they’d have a big feed. Those rabbits were everywhere—I mean, rabbits, rabbits.

SCHWARTZ: I can remember tumbleweeds everywhere. When the wind came, they rolled, and it looked like a herd of cows running through the fields.

V. Rain

On January 13, 1957, President Eisenhower and Agriculture Secretary Ezra Taft Benson arrived in San Angelo as part of a six-state drought inspection tour. In West Texas the president took a 22-mile drive to examine the devastation. “Eisenhower tramped the Southwestern drought lands on Monday and promised on the part of the government that ‘everybody will do his best’ to provide drought relief,” wrote a reporter for the Associated Press. But the most memorable feature of the presidential visit was what happened immediately afterward. On January 14, the San Angelo Standard-Times noted that “at least one spectator observed that the moon was nearly full and that it had a ring around it. ‘Doesn’t that mean rain?’ he asked, implying that the President’s visit may be a good omen. ”

Indeed it was.

PEGGY KELTON, 77, is the wife of Boob Kelton. Elmer used to say that San Angelo had always been a Democratic town until President Eisenhower visited in January 1957 and made his speech. After he left it started raining, so they soon became Republicans—and still are.

PATSY ECKERT: My uncle, Sonnie Noelke, lived out at the ranch. He had a great big overstuffed chair, and he pulled it over to the door and let the rain come in on him. He had a large mason jar full of Cutty Sark and water, and he sat there and just celebrated the end of the drought.

WHITTLEY: There were people standing outside, and it just rained and rained and rained, and everybody was dancing around in our neigborhood. We still didn’t think the drought was broken, though, because you know ranching people are always looking for the next rain. They can get a twelve-inch rain and they’ll say, “Yeah, but we sure do need another one.”

WRIGHT: We had a party line, and ’course when the phone would ring it probably wasn’t for you, but you’d answer anyway. And I got on that phone, and two ranch ladies were talking: “It’s coming now! I just heard on the radio, it’s coming.” Henry Howell [host of a popular farm and ranch program on San Antonio radio station WOAI] said, “It’s coming, it’s coming.” And by God, it did.

HELEN LEWIS, 80, was a young housewife in San Angelo in the fifties. All the creeks flooded, and everybody would go out to watch them running over the road. It was thrilling because we were always praying for rain.

RANDALL CONNER, 62, is the economic development director in Winters. I do remember when the floods started coming in ’57. There was a creek near our house, and the frogs would start croaking. The frogs came from everywhere. That was just a memorable event when that big rain came.

BOOB KELTON: When it started to rain again, well, it was just good. You could go somewhere. Whenever you’re feeding every day and taking care of this livestock, you can’t go anywhere. Once it started to rain, you could take a vacation if you needed to. Like right now I haven’t had a vacation in years. But I don’t really have anyplace to go anyway.

ROSS: It made some people think, “Hey, I need to have a different education. I need to be prepared.” My daddy said, “You go get your vet degree, and you can put your satchel and your books and your family in a car and you can go where it rains,” and that’s what I did.

MERTZ: My father thought he was the last stocker. He ran sixty animals to a section, and I guarantee if you run fifteen to twenty animals now you’re about to the limit of it. The land used to be more productive, and you could run a lot more livestock. And with each subsequent drought it would come back less. We lost topsoil, we lost the better grasses. You don’t see ’em anymore.

WHITTLEY: I still, when I go to brush my teeth, I wet my toothbrush and turn off the water. Think how long that’s been.

CHIP LOVE, 55, the president of Marfa National Bank, grew up in an old ranching family in Presidio County. After the fifties drought was over, some ranchers decided they needed to do something else besides ranch. A new generation of rancher was born. My step-dad started doing oil and gas and chartered a bank so he wouldn’t be completely dependent on a ranch. Before that, it was all about living the rancher’s life. The drought made people look at their hole card.