You’d be forgiven for thinking that the best days of Texas film are past. In all our big cities—the places where most movie production happens—it’s gotten difficult to find the sort of cheap rents that budding filmmakers depend on. And the Legislature’s on-and-off-and-on-again willingness to fund an incentives program (see “Final Cut”) has made it a lot tougher to get movies made here. Surely, you think, we won’t see another Slacker or El Mariachi or Texas Chain Saw Massacre anytime soon.

Yet, somehow, the legacy of Richard Linklater, Robert Rodriguez, and Tobe Hooper lives on—and not just in Austin, where the modern Texas film industry first took shape. Places like Houston, Dallas, and, yes, Laredo are fostering ambitious young directors who are interested in making independent art-house cinema, blockbuster features, and incisive documentaries. And many of them—despite the skyrocketing cost of living, despite the hostility from the Lege—are staying put rather than moving to L.A. or New York.

Here are ten directors—many of them are screenwriters too, and a few are actors as well—who will be making Texas proud for years to come. —Jeff Salamon

![]()

David Lowery

Hollywood is calling David Lowery, but he’s staying put in Dallas. Later this month, Lowery, director of the 2013 festival favorite Ain’t Them Bodies Saints and last year’s Disney remake Pete’s Dragon, debuts his third feature, A Ghost Story, starring Casey Affleck and Rooney Mara. With a major-cities release and rave early reviews, it should earn a big multiple on its $150,000 budget. But Lowery’s haunted-house script feels nothing like Hollywood business as usual. It’s not horror—Affleck plays a sullen, bedsheet-wearing ghost who watches as his wife, Mara, mourns his passing. Nor is it a remake of a Patrick Swayze flick; instead of veering into supernatural-romance territory, A Ghost Story expands into a gorgeous, cosmic meditation on impermanence and the tangled meaning of home. “I spent a great deal of my youth wanting to leave Dallas and go to New York or Los Angeles,” Lowery says. “At a certain point, that ceased to be important to me. What was important to me instead was making things that felt like personal expression. I had the means to do that in Dallas.” The visionary success of A Ghost Story assures that Hollywood will now come to meet Lowery on his own ground. —Michael Agresta

![]()

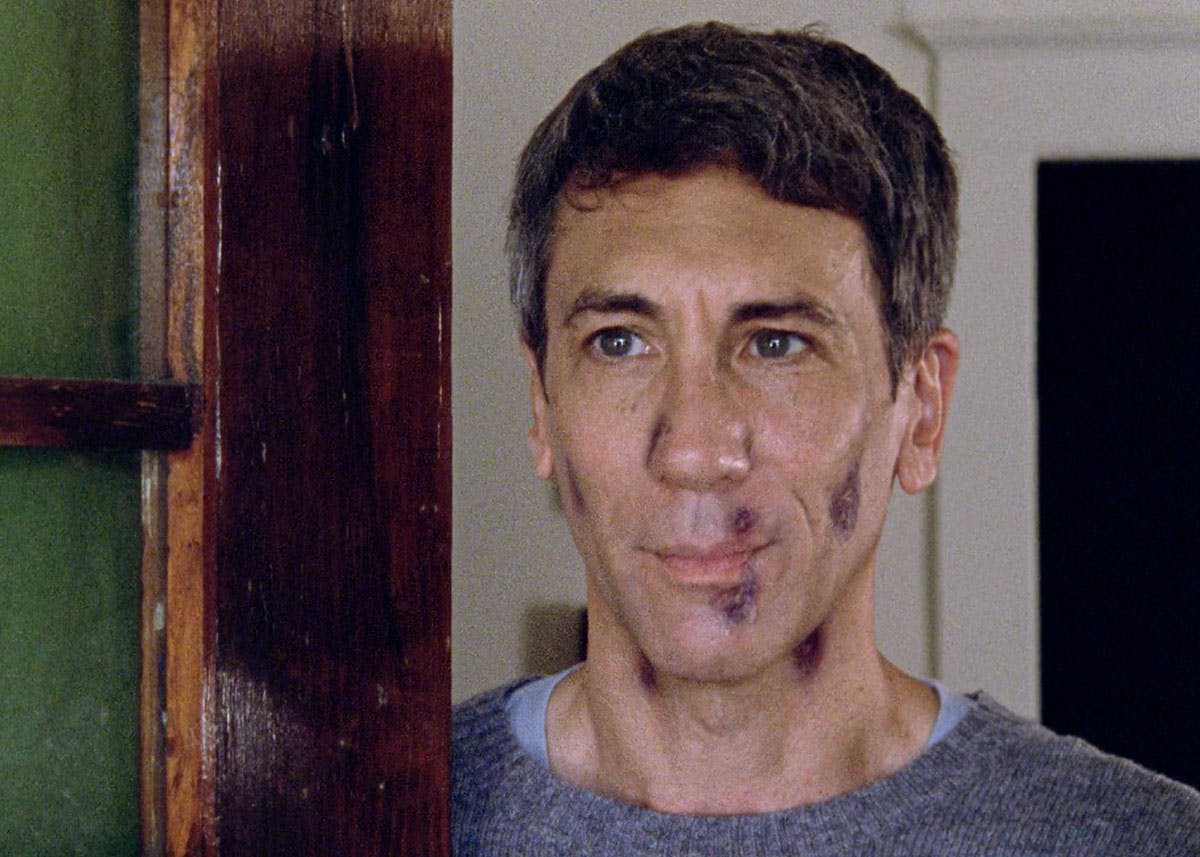

Shane Carruth

Since the 2004 release of his time-travel brainteaser Primer, shot in the Dallas suburbs where he lived, autodidactic auteur Shane Carruth has released just one other film: 2013’s Upstream Color, an even more challenging feature that alienated some viewers while bolstering his rep as a Kubrickian visionary. Where other no-budget filmmakers might rely on exposition to tell what they can’t show, Carruth went in a different direction, creating a dense rebus puzzle of imagery—worms, pigs, orchids, and the sounds of the planet—and demanding that we invent our own decoder rings. As of late 2015, prospects were rosy for his high-seas epic, The Modern Ocean; Anne Hathaway, Keanu Reeves, and Daniel Radcliffe had agreed to star in it. But then a year passed with no news of a production date, suggesting that the film may have met the same fate as A Topiary, the effects-laden sci-fi adventure he tried and failed to make after Primer. Though often secretive (he shot Upstream Color quietly in North Texas, unbeknownst to Hollywood), Carruth hasn’t been invisible. He did a bit of acting, wrote music for the TV show The Girlfriend Experience (co-created by his fiancée Amy Seimetz), and even co-directed a documentary about big data for the National Geographic series Breakthrough. But a new feature? Given Carruth’s history, that may arrive when we’re least prepared for it. —John DeFore

![]()

Alfonso Gomez-Rejon

Though it was his second film as a director (a little-seen thriller set in Texarkana was the first), the 2015 Sundance arrival of Me and Earl and the Dying Girl played out like a dream debut for Laredo native Alfonso Gomez-Rejon: standing ovation, the Grand Jury Prize, and a bidding war that reportedly reached $12 million. Adding his own film-geek references and techniques to the novel he was adapting, Gomez-Rejon gave his teen hero a quirkier POV than might have been expected and set the pic apart from the usual young-adult pack. Then, as happens to so many Sundance hits, the movie bombed in theaters. But Gomez-Rejon had been around long enough not to let that throw him off course: having worked on hits including Argo and earned awards for TV directing (American Horror Story: Coven), he was well connected enough to make a quick rebound. Gomez-Rejon dodged a bullet when he quit the Will Smith bomb-to-be Collateral Beauty over creative differences, and he now has at least four directing projects reportedly in development, ranging from an action comedy about macho filmmaker Sam Peckinpah to a script by chick-flick hitmaker Delia Ephron. But first: December’s The Current War, a prestigious-looking drama in which Benedict Cumberbatch plays Thomas Edison. —J.D.

![]()

Yen Tan

When the queer romance Pit Stop debuted at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, it announced the arrival of a refreshingly new voice: writer-director Yen Tan, a 42-year-old Malaysian immigrant to Dallas who understands intimately what it means to be gay and feel deeply out of place in Texas. In the years since, though, Tan has run into a familiar brick wall: a Hollywood culture that rarely finds room for alternative stories. “The bar that gets set for minority filmmakers or women filmmakers is so high, way higher than for a white male filmmaker,” he says. “And it’s harder to get another chance if we fail.” Happily, Tan, who is now based in Austin, has found his way through the stalemate. In 2016 he premiered at South by Southwest a lovely nine-minute short called 1985, about an AIDS–afflicted man preparing to move back home with his mother. The response was so favorable that Tan decided to transform it into a feature film, which has attracted an impressive cast, including Michael Chiklis (The Shield), Cory Michael Smith (Gotham), and Virginia Madsen (Sideways). Tan says he hopes to have the film completed in time to submit for the 2018 edition of Sundance. His is a voice—quiet yet urgent and deeply affecting—that needs to be heard far and wide, and much more frequently. —Christopher Kelly

![]()

Trailer for “Dear White People.”

Justin Simien

What a difference a few years—and Netflix’s move into commissioning original content—makes. When Houston-born writer-director Justin Simien’s 2014 film Dear White People, about an Ivy League campus rocked by a racially offensive fraternity party, opened in theaters, its blast of prickly satire seemed to confound critics and audiences. (The New Yorker, spectacularly missing the point, said it “plays like a liberal-establishment calling card.”) But in 2016, Simien struck a deal with Netflix to transform his feature film into a ten-episode series, one that dug deeper into its characters, offered a complex exploration of such buzzwordy concepts as white privilege and black “woke-ness,” and proved powerfully attuned to our ongoing, roiling conversations about black lives in America. The show dropped in April, and this time Simien’s work earned raves (“A near-ideal comedy for our age,” per USA Today) and instant “must-binge” status. Simien has said he’s eager to tackle other projects and prove himself more than a one-trick pony. For now, though, the 34-year-old auteur has created arguably the year’s most exciting television show, not to mention a fertile creative space for other minority filmmakers. (Simien helmed three of the series’ episodes himself, but others were directed by Chutney Popcorn’s Nisha Ganatra, Moonlight’s Barry Jenkins, and Mississippi Damned’s Tina Mabry.) Another season, please. —C.K.

![]()

Noël Wells

Most audiences will recognize Noël Wells as an actress from her one-season stint on Saturday Night Live or from her recurring role on Aziz Ansari’s Netflix series Master of None. But Wells, who grew up in San Antonio, Boerne, and Victoria before attending UT-Austin, has always seen acting as a stepping stone to producing her own material. “In comedy, you have your voice, and you want to express it,” Wells says. “The only way to really do that is if you’re in control of the whole process.” So far, so good: Wells’s first feature film, Mr. Roosevelt, captured an audience award at this year’s South by Southwest Film Festival. It’s a lo-fi, self-aware, quarter-life-crisis movie for the hipster generation—a comic tale of revisiting home, attempting to recapture lost youth, and learning to accept change. Home, in this case, is rapidly evolving Austin, which has become a sort of muse for Wells, even though she now lives in Los Angeles. Next up is a pilot for Comedy Central, also set in Austin, shooting this summer. “There’s just so much there from my past that I’m still trying to unpack,” says Wells, who has lived away from Texas for seven years. “It’s like a character in my head, all the time.” —M.A.

![]()

Trailer for “Queen Sugar.”

Kat Candler

If, as Tolstoy observed, all happy families are alike, filmmaker Kat Candler has made a career of deconstructing the ones that are unhappy in their own way. Hellion, the most recent of her three Sundance Film Festival premieres, is a disaffecting feature that stars Juliette Lewis and Breaking Bad’s Aaron Paul in a deft meditation on fatherhood, loss, and the bond between brothers. An earlier short, Black Metal, uses the relationship between a girl and her guilt-ridden musician father as a vehicle for self-reflection. “Whether it’s the world of Southeast Texas or [heavy] metal, I always gravitate toward parent-child relationships and family stories,” says the Austin-based Candler, who is once again training her lens on complicated families, this time in collaboration with Selma director Ava DuVernay, whom she befriended at Sundance in 2011. After directing four episodes of Queen Sugar, DuVernay’s cable drama about three siblings who return to Louisiana to run their late father’s sugarcane farm, Candler was named producing director for the show’s second season. In that role, she’ll oversee Queen Sugar’s roster of all-female directors, helping them evoke the raw authenticity she always strives for. “There’s such beauty in portraying the dynamic of family, which everybody experiences,” she says. —Beejoli Shah

![]()

Trailer for “It Comes at Night.”

Trey Edward Shults

Trey Edward Shults’s 2015 drama Krisha had all the trappings of a groan-inducing, indie movie cliché: It was shot in only nine days, almost entirely inside the director’s mother’s house in East Texas, with a cast composed largely of the writer-director’s own family. The budget was under $100,000. But if the 28-year-old Shults’s scale was modest, his ambitions were immense, and Krisha—revolving around a fraught Thanksgiving dinner, and suggesting an unnerving cross between Roman Polanski’s Repulsion and Jodie Foster’s Home for the Holidays—caught fire. Following its South by Southwest premiere, the film earned Shults an invitation to Cannes, an Independent Spirit Award, and a two-picture deal from distributor A24. Now comes Shults’s second feature film, It Comes at Night, set in a mysterious near-future where the country has been ravaged by a plague. The film, which opened last month, at first seems like a conventional survivalist thriller, about a mysterious couple seeking refuge with another family. But Shults (who cut his teeth interning for Terrence Malick) keeps pushing into ever darker and more surreal terrain, suffusing each scene with dread and paranoia and offering up a fearless commentary on our current xenophobic moment. Just like Krisha, it’s a genre movie that simultaneously reinvents its genre. Jump on the bandwagon now. More likely sooner rather than later, Shults is going to be a very big deal. —C.K.

![]()

Ivete Lucas and Patrick Bresnan

Husband-and-wife team Patrick Bresnan and Ivete Lucas make films about American communities off the beaten track. “I’m very fluid with culture,” says Lucas, who was born in Brazil, educated in Mexico, and went to film school at UT. “I think that plays a lot into what we do as filmmakers. We are able to go anywhere and relate to people at a deeper level.” Lately, the Austin couple’s focus has been Pahokee, Florida, a poor inland community just miles from the splendors of Palm Beach, where they shot two Sundance-selected short documentaries: The Send-Off (2016), which chronicles the rambunctious preparations for Pahokee High School’s prom, and The Rabbit Hunt (2017), which captures a local tradition that accompanies the seasonal burning of sugarcane fields. Both are lively, fly-on-the-wall observations of a way of life rarely represented in the movies. Next, the couple is at work on a feature-length documentary about the life-defining challenges of the local high school’s senior year. “We both like people,” says Lucas. “When we work with a community and make films, it’s always more about the relationships than the film itself.” —M.A.

![]()

Chelsea Hernandez

An Austin native who spent the better part of her childhood co-hosting an educational program on public access television, Chelsea Hernandez decamped to New York City for school and quickly scored some valuable industry internships. But when a family health scare brought her back home, Hernandez found herself increasingly drawn to Austin’s filmmaking scene. After spending the past three years as a producer and director at local PBS affiliate KLRU—where she helmed the Emmy-winning documentary series Arts in Context—Hernandez is now shifting into feature-length documentary mode and taking on a slightly bigger task: giving a voice to all Texans. The film she’s working on now, Building the American Dream, aims to put a face on the undocumented immigrants working in Texas’s multibillion-dollar construction industry and their efforts to organize. “I’m a very curious person,” says Hernandez, a graduate of UT-Austin’s radio-television-film program. “When I was younger I thought I was going to go into broadcast journalism. And then I realized I didn’t want to be on camera. But I get joy from seeing new worlds, meeting new people, and learning new things.” —B.S.

- More About:

- Film & TV