By the early seventies, the Latin American Boom was in full swing in the United States. South American, Central American, Mexican, and Caribbean writers like Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, and Mario Vargas Llosa were feted in the pages of the New York Times, compared to Faulkner and the anonymous authors of the Bible, and taught at the university level. Contemporary Latino literature had finally found some respect on our shores.

Or so it seemed to the outside observer. Nicolás Kanellos knew better. A native New Yorker with Puerto Rican roots, Kanellos was working as an assistant professor of Hispanic literature at Indiana University Northwest when Márquez and the rest made their names. He was glad for their success, but he recognized that something was missing from all that acclaim: recognition of the work being done by Hispanic writers in the United States. American critics were enamored of the work coming out of Colombia, Peru, Cuba, and Mexico. But the writing emerging from the Bronx, South Texas, and Los Angeles? Not so much. “At that time, the idea of what it meant to be a Latino in this country wasn’t being documented,” Kanellos says.

To counter that neglect, in 1973 Kanellos and Luis Dávila, a professor of Latin American and Latino literature at Indiana University Bloomington, created Revista Chicano-Riqueña (Chicano–Puerto Rican Review) to publish and celebrate the work of Latino authors and artists. To get copies out to the public, the two men took an unorthodox approach: they would show up at Chicano activist events, such as picket lines and rallies, and maneuver through throngs of protestors, hawking copies of their magazine for $7 apiece. “We were out at street festivals, attending school board meetings pushing for bilingual education, or meeting with community organizers—pretty much anywhere there was activity going on,” he says. “Word got out pretty fast that we existed and this was a place to publish.”

Nearly a half century later, that fraught beginning has led to something Kanellos could have scarcely imagined back then: tonight, Arte Público Press, the Houston-based publisher that Kanellos founded in 1979 to build on Revista Chicano-Riqueña’s success, will receive the Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Book Critics Circle—a designation typically given to individual authors. “Arte Público’s determination to build bridges, not walls, has immeasurably enriched American literature and culture,” the NBCC noted. “The books they’ve published have endured over the past decades and have become new classics of American literature,” NBCC board member Michael Schaub, one of the critics who voted on the award, said. “If not for Arte Público, they might not have had a home.”

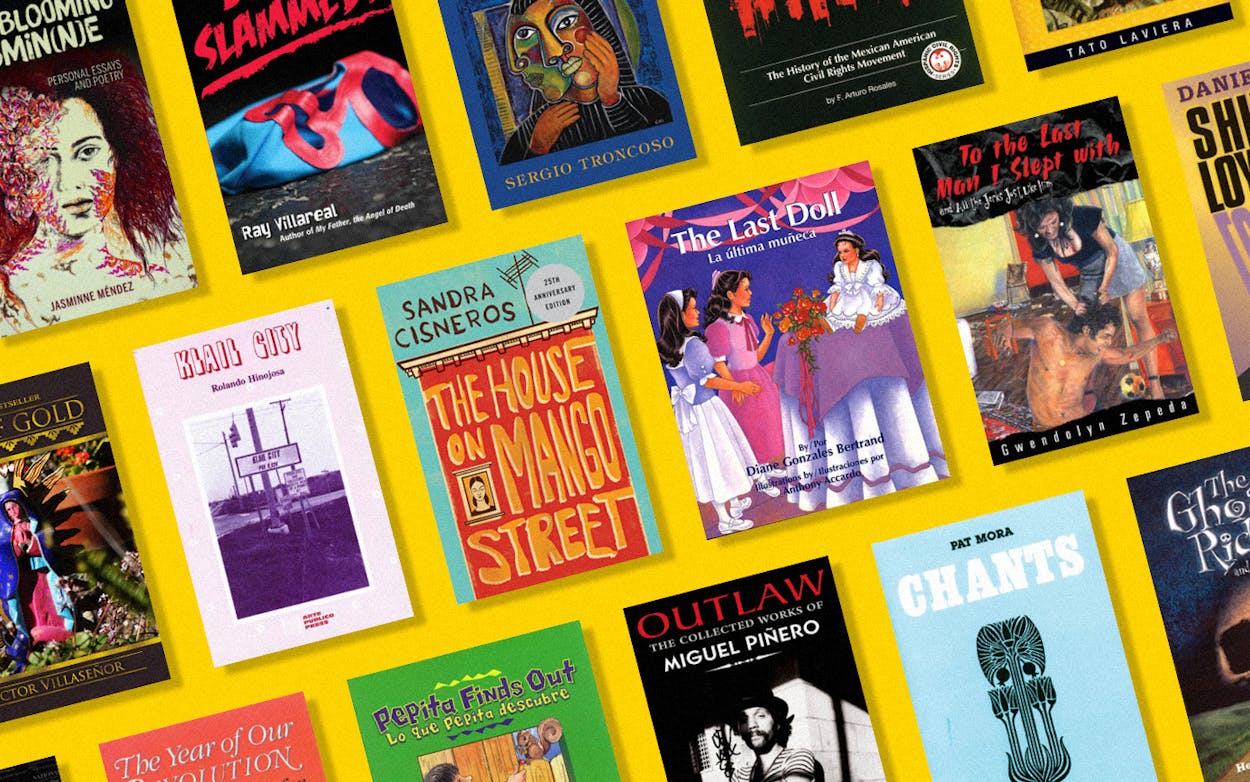

Arte Público, the country’s oldest and largest publisher of contemporary Hispanic literature, has published hundreds of books. Among them have been major successes, such as Victor Villaseñor’s 1991 best-seller Rain of Gold and much of University of Texas at Austin professor Rolando Hinojosa-Smith’s Rio Grande Valley–set Klail City Death Trip series. The publisher’s most well-known book is The House on Mango Street, the 1984 bestseller by author and onetime San Antonio resident Sandra Cisneros. Today, Arte Público publishes dozens of books a year and has spun off two sister entities, the Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage project, which publishes “lost” Latino literature of the past two centuries; and Piñata Books, which publishes children’s and YA books. (Revista Chicano-Riqueña changed its name to The Americas Review in 1986 and ceased publication in 1997.)

Kanellos launched Arte Público just before he moved to Texas in 1980 to take a job as a professor at the University of Houston. (He received his PhD from the University of Texas at Austin in 1974.) His motivation was much like his motivation when he launched Revista Chicano-Riqueña; at the time, the Hispanic population in the U.S. was growing phenomenally, and the majority of U.S.-born Latinos were fluent in English. Yet most publishers ignored this growing audience—they didn’t seem to realize that Latinos spoke English, much less wrote it. “Our experience was being erased by an industry that still very much ignores our demographics,” Kanellos says.

But Latinos were writing. Since the thirties, folklorists Américo Paredes and Jovita González had been capturing their experiences as Mexican Americans caught between two cultures. In 1971 Tomás Rivera’s . . . And the Earth Did Not Devour Him, put out by a small Hispanic publisher in Berkeley, California, painted a vivid picture of life as a South Texas migrant worker. Kanellos thought that if he started publishing such books, he’d be able to expose them to a wider readership by way of the academy. The rise of Chicano and Latino studies courses across the country, he believed, would create a demand for Hispanic works.

He was partly right. The early orders he received from teachers and students helped Arte Público get its foot in the door. But it wasn’t until 1988 that the door blew wide open. A handful of prominent universities, most famously Yale, Harvard, and Stanford, led the charge to diversify the classic authors taught in college by replacing required readings from Plato and Voltaire with Zora Neale Hurston and Cisneros. The change to Stanford’s freshman Western Culture course sparked a national debate that led to outraged editorials in major publications. One from the Wall Street Journal ran beneath the headline “Stanford Slights the Great Books for Not-So-Greats.”

It’s an insult Kanellos still remembers verbatim.

But the controversy only increased demand for Latino writing. “That debate put us on the map,” Kanellos says. “It wasn’t until then that we started receiving orders for books like The House on Mango Street from bookstores.”

The success of The House on Mango Street created space for the next generation of authors. Gwendolyn Zepeda had never considered a career as a writer until she read Cisneros in college. It wasn’t that she didn’t want to be an author, it was just that she’d never seen another Latina do it. “When you’re raised without a lot of Latino writing, you grow up with a really stunted idea of what stories represent our community,” Zepeda says. In 2004 Arte Público published her first short story collection, To the Last Man I Slept With and All the Jerks Just Like Him; nine years later, she was named Houston’s first poet laureate.

For many Arte Público authors, the house’s willingness to publish their work isn’t its only appeal. Just as important is that Arte Público understands both the writers and the audience they’re trying to reach. Diane Gonzales Bertrand, a San Antonio–based children’s book author, faced years of rejection from publishing houses in New York, whom she says didn’t understand her experience. Two decades ago, when she pitched her book The Last Doll—a story about the traditional gift given to a young girl at her quinceañera—she says one publisher was confused about the premise, questioning why a fifteen-year-old girl would be receiving a children’s toy. “The people at Arte Público immediately understood it,” she says. “I wasn’t constantly having to explain my culture.”

Today, the sort of work Arte Público has long fought for is now an established part of the mainstream. Authors like Junot Díaz, Julia Alvarez, and Luís Alberto Urrea write best-selling books for major commercial publishers. (After Mango Street, Cisneros herself left for Random House and went on to win the National Medal of the Arts, a PEN/Nabokov Award, and a MacArthur Fellowship.) Rolando Hinojosa-Smith received the lifetime achievement award from the NBCC in 2013. A debut novel Arte Público published last year, the border-set Bang, by Houston writer Daniel Peña, received strong reviews from Publishers Weekly and Kirkus. Tonight’s honor at the NBCC event is simply a confirmation of what anyone who has been paying attention already knew.

“Our writing has always existed. It was just always ignored,” Kanellos says. “We have a literary legacy in the United States, but it’s been treated as foreign for two centuries, when this was actually its home.”