All due respect to Ireland and its musicians, but the greatest trick the devil ever played was to permanently associate the phrase “take me to church” with Hozier. Before a milquetoast single by that name dominated the 2013 pop charts, the act of “taking ____ to church” was a colloquialism in African American Vernacular English that referred to a musical or sermonic performance so moving it could instill in both performer and audience a feeling of the presence of God.

The exact origin of the phrase is unclear, but it was almost certainly born of the gospel traditions in Black churches, where preachers and choirs aim to elicit a profound emotional response and fill parishioners with the Holy Spirit. Even those who don’t care for religious terminology can recognize what that means. It is the moment when some divine combination of notes, rhythm, volume, and energy makes you hold your breath a little, overwhelming you with some combination of joy, grief, and a host of other intense emotions you may not even be able to name.

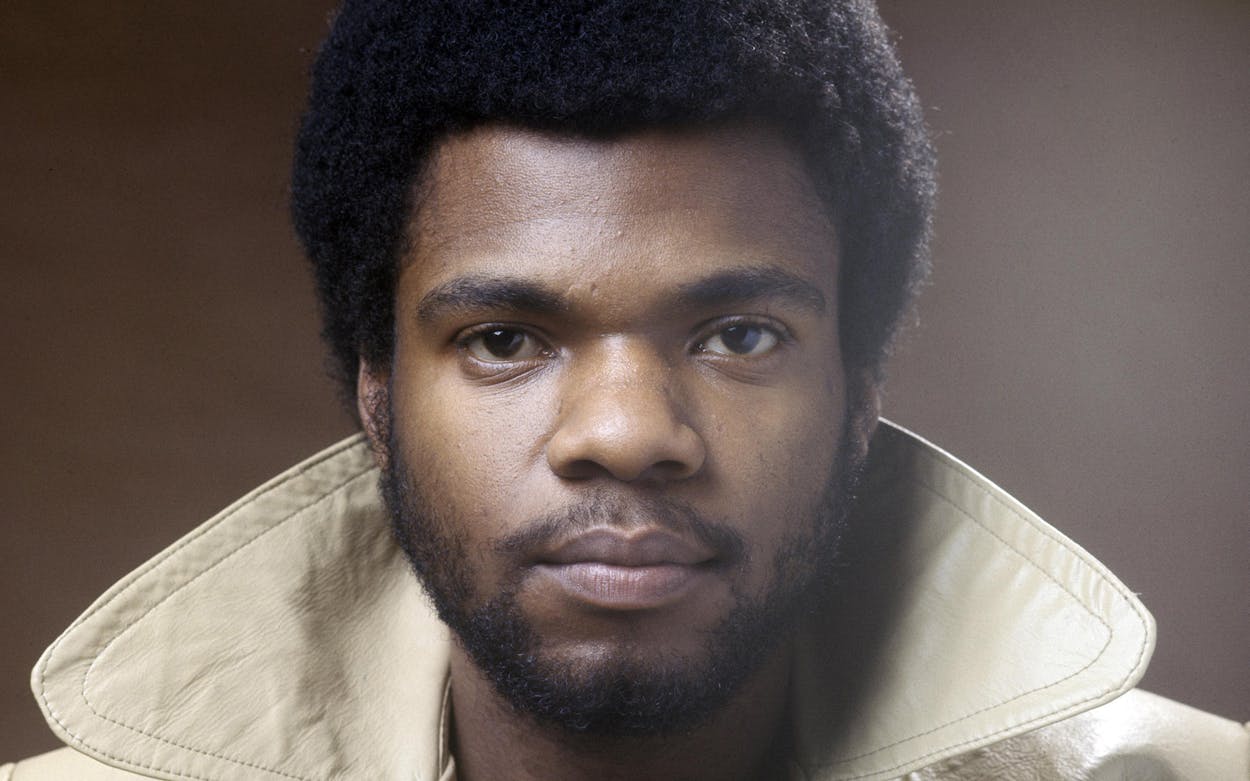

Forgive the philosophizing. I only do so because the art of “taking people to church” is the phenomenon at the heart of the documentary Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It, which premiered at SXSW this year. A biography of the Houston-born organ prodigy who was credited with “saving” the Beatles during their contentious Get Back sessions, the film is much more than a list of Preston’s myriad contributions to twentieth-century pop, soul, and rock and roll music (he played with Little Richard, Nat King Cole, Ray Charles, the Beatles, Sam Cooke, the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Sly Stone, and more). Through footage of Preston’s performances and interviews with his close friends and early collaborators in the Los Angeles gospel music scene, the documentary is a study of the fifth Beatle’s transcendent musicianship, and the skill and passion that captivated not just fans but the best and most powerful musicians of his time.

Preston was born in Houston in 1946, and by the time he turned three, he was showing prowess behind the keys. At nine, he was already playing the organ at a professional level—that’s when his mother moved them to Los Angeles so her prodigy son could make his way in the gospel music industry. By ten, he’d become part of the touring band for Mahalia Jackson. At eleven he was performing on television (with Nat King Cole) and in films (a role in the 1958 picture St. Louis Blues.) At sixteen he toured with Little Richard, where he met the Beatles for the first time in Hamburg, Germany, in 1962. Five years later, he joined Ray Charles’s band. His biggest break came two years later, when he swung by Apple Studio on Abbey Road at the request of his friend George Harrison. Preston was so compelling on the piano and the Hammond B-3 organ that the then-quarrelsome quartet enjoyed working together in that recording session, and they asked Preston to come back every day. He is the only non-Beatle to have been credited on not one but two of their tracks (“Get Back” and “Don’t Let Me Down.”)

Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It gets into all that, plus the years after, when Preston released his own chart-climbing singles “That’s the Way God Planned It,” “Outa-Space,” “Will It Go Round in Circles,” and “Nothing From Nothing.” It shows videos of his performances at the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh, on tour with the Rolling Stones, and stealing on-stage thunder from the likes of George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Sam Moore, and then some. The film opens with a scene from the Concert for Bangladesh, when Preston starts playing “That’s the Way God Planned It” on the Hammond with such zeal that he eventually rises from the bench and dances his way to the front of the stage, taking all 20,000 concertgoers from Madison Square Garden to church.

When Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned It focuses on Preston’s almost-metaphysical musical gifts it succeeds as a poignant examination of the relationship between music, selfhood, joy, and spirituality. Preston maintained throughout his life that his talent was a gift from God. It is equally clear from his personal struggles—alcoholism, drug addiction, and legal troubles that eventually landed him in prison—that he also struggled with his relationship to God and the church. It was both the source of his greatest joy, music, and his lifelong pain, as he struggled to come to terms with his sexuality.

The documentary runs into trouble when it focuses a little too heavily on the latter. Preston was famously very, very reserved, and through interviews included in the film it is clear that he did not address his homosexuality with even his closest and most beloved friends. “He lived his life in the closet” is an easy answer to the question of what plagued Preston, but the filmmakers don’t seem to have the material to back up that assertion.

Some of the documentary’s participants felt the same way. Joyce Moore, Sam Moore, Ken Burke, and others filed suit last week to try and halt the release of the film they see as nothing but the salacious outing of a man who did not publicly identify as gay until he was days away from his death. I think the film is more than that, but one can’t help but feel the film forces a moral to the story of Billy Preston that says more about the modern documentary audience than it does about its subject.

The audience at the March 12 showing of the film got loud two times during the screening. First, they booed at the SXSW montage featuring sound bites from the festival’s many panels about artificial intelligence. Then the crowd clapped at the end of the film, just after the credits began to roll, when a clip of Preston just winging it at the Hammond B-3 in Apple Studio flashed across the scene screen. His fingers dance across the keys, his head bobs, and his body sways side to side. He furrows his brow in concentration and then busts out that incredible, contagious, beaming, gap-toothed smile. When he stops playing he laughs from the joy of all he’s just done. It was so lovely, I stopped breathing for a bit.