The race at Rodeo Austin should have been just one more rung on Martha Josey’s climb through barrel racing history. She was already rodeo royalty—a former world champion and National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame inductee—and on this dry, pleasant March evening in 2004, she hoped to qualify for the national barrel racing finals for a fifth consecutive decade. Her boots jammed into the stirrups, Josey waited in the alleyway connecting the main arena to the parking lot. The muffled cheers of spectators wafted from the bleachers above. She was seconds from her first run; the competitor with the fastest total time after three rounds would win. With her hat pulled low and red lipstick bright enough to see from the rafters, she felt the rhythmic breathing of her horse, Red Man Bay, a gelding with an odd fondness for Dr Pepper.

As soon as she heard her name over the loudspeaker, Josey leaned forward, a signal to Red Man Bay that their moment had come. Barrel racing is the only pro rodeo event in which riders enter the arena at a full run. Red Man Bay began to walk, then shifted from trot to gallop to sprint. They burst into the bright lights and looped around each of three barrels, Josey’s dark hair flying. In 15.58 seconds—a tie for the fastest run so far that night—it was over.

Her horse raced back into the dimness beneath the stands. They continued down the alley, toward the concrete breezeway, where a gate stood open. Then, just as she reached it, someone swung the gate closed, not knowing a horse and rider were strides away from the threshold. Panicked and unable to stop, Red Man Bay attempted a jump, but his chest slammed into the steel bars. Josey was catapulted like a rag doll over the top and thrown facedown onto the pavement on the other side.

An emergency medical crew arrived within minutes and found Josey unconscious, with blood oozing from her nose, ears, and scalp. The paramedics cut an incision into her side to release the fluid pooling around a collapsed lung, then loaded her into an ambulance headed for Brackenridge Hospital. Veterinarians saw to Red Man Bay. Josey’s close friend Deb Brown, who had been at the arena, rushed to the hospital and found Josey on a gurney in a treatment bay, unmoving, as doctors frantically tried to stabilize her fading heartbeat. Her husband, R. E. Josey, told Brown he wouldn’t go near her because he couldn’t bear to watch his wife die.

Brown, a cop and former paramedic, recognized in Josey the sunken, ashen look of a human body losing its grip on life. She clasped Josey’s hand and gently encouraged her friend to hold on, fearing her wounded lungs would soon be spent.

At some point, Josey heard Brown’s voice. Without opening her eyes, Josey gradually regained consciousness. In a faint murmur, she asked where she was. She asked about her horse. And then—blood still caked in her hair—she asked, “Deb, am I winning the barrel race?”

In rodeo, known for crowd-pleasing feats of endurance and brute strength, barrel racing is an anomaly: a quarter minute of grace and speed—a thousand-pound animal on candlestick legs, weaving a tight cloverleaf pattern around three 55-gallon drums spaced out in a triangle. This is where cowgirls are made. Although Annie Oakley made history as Western riding’s first female superstar, captivating audiences with her sharpshooting in Buffalo Bill’s variety shows in the late 1800s, women became largely shut out as rodeo developed into an organized sport throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Then, in 1948, a group of women—mostly wives and daughters of farmers and ranchers—met in San Angelo and formed what they called the Girls Rodeo Association, with barrel racing as its premier event.

In those days, barrel racers were equal parts decoration and athlete. Their duties weren’t just to compete but also to carry various state and national flags during opening ceremony rites at rodeo events. It was all about, as Josey recalled, “fast horses and pretty women.”

Today, after decades of fights to assure fair pay, prize money for barrel racing is equal to that for bull riding and other male-dominated events. In 1981 the Girls Rodeo Association became the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association. It remains the oldest women’s professional sports organization in the country, boasting $7 million in annual payouts. A proven barrel racing horse can fetch as much as a new Ford F-350.

Sports tend to reward the young, with most athletes peaking in their twenties and thirties, before their bodies age out. Charmayne James, the most decorated barrel racer in history, won her first of eleven world championships at 14 and retired in 2003, when she was 33. Martha Josey turns the sports world’s fealty to youth on its head. She was approaching 30 before she even started racing at the elite level; she didn’t win a world championship until she was 42, and she last qualified for the National Finals Rodeo at 60. Five years later, she won a race that landed her on a Wheaties box.

Competitors earn their spots in the NFR, the annual Super Bowl of rodeo, by ranking among the top fifteen money-winners in their event over the course of a season. Josey made the NFR in the sixties, seventies, eighties, and nineties. Nolan Ryan’s 27 seasons in the major leagues are a remarkable achievement, but Josey’s longevity ranks her among the longest-competing professional athletes in American sports history. Imagine Serena Williams qualifying for the U.S. Open in 2045—and then making the round of 16.

Josey was 66 on the night she crashed to the ground in Austin. Her pelvis was shattered. Her skull and six ribs were fractured. And still she had no intention of giving up.

When she was a teenager, the only sport Martha Arthur—Josey’s maiden name—knew was basketball. She grew up in northeast Texas, where her father raised and sold quarter horses (named for their speed over a quarter mile). As a young girl, she rode before she could stand, tucked into the front of her dad’s saddle like a cowboy BabyBjorn. When she was ten, her father died of a heart attack, and her mother sold all of their horses except a stallion named Jimbo, so that Josey and her brother would still have one horse to ride. The family moved in with Josey’s paternal grandmother, a nightclub and dance hall owner who lived in a sprawling, two-bedroom brick house on more than two hundred acres of Piney Woods between Marshall and Karnack.

During her sophomore year at Karnack High School, Josey, who would go on to become homecoming queen, tried out for the basketball team. “The first day that I went out for the coach to play basketball, she said, ‘Do you like to win?’ ” Josey recalled. “I said, ‘I love winning.’ She said, ‘Okay, we’re going to practice.’ ” Josey would not leave school each day until she had sunk a hundred free throws. “I found out that you could win basketball games by making free throws,” she said. “And I became a very, very good basketball player. But [Coach] also taught me that practice doesn’t make perfect—perfect practice makes perfect.”

Shortly before graduating high school, Josey and two friends, in their poodle skirts and bobby socks, piled into a car and drove 45 minutes down U.S. 80 to see a rodeo in Shreveport, Louisiana. From the opening ceremony, she was hooked. The grandeur, the crowds, the patriotic swell of “The Star-Spangled Banner”—she knew right away she’d be a cowgirl. The next day, she took Jimbo out of his stall, set up a barrel in her grandmother’s pasture, and began to practice. She hadn’t ridden in eight years.

After high school, Josey took a secretarial job at the Longhorn Army Ammunition Plant, near the banks of Caddo Lake. On weekends, she would rent a trailer for $5, hitch it to her mother’s old two-tone Buick sedan, and haul Jimbo to races. The intense focus required to shoot free throws under pressure had taught her that mental strength often separates great athletes from good ones—that a race can be won or lost in the moments before a horse starts running. Basketball had also left her with the dexterity and coordination to rein her horse and grab the saddle horn without looking at her hands. To win, a rider must always look where she wants to go; everything is achieved by feel. (Even today, when Josey hosts rodeo clinics, she tells aspiring barrel racers to find a ball and learn to dribble without looking down.)

Yet she would have likely stayed a moderately good barrel racing hobbyist had she not met a half-thoroughbred named Cebe Reed, in 1960. Cebe was named after his owner, a Longview rancher named C. B. Reynolds who had known Josey’s father. He was trying to sell the horse but couldn’t attract an offer that satisfied him. Cebe had some unfortunate habits for a barrel horse—most notably, he had a one-and-done mindset, wanting to circle only a single barrel before scurrying back to the gate. He also didn’t look like a typical barrel racing horse. He used his long, thoroughbred gait to charge full force toward the barrel, then dropped his hindquarters so low that his tail dragged on the ground while he turned and slid around, pulling forward with his front hooves. He held his head high instead of bending it toward the turn. Yet, somehow, he never lost his forward momentum.

Reynolds asked Josey if she would ride Cebe in regional rodeos to show prospective buyers what the horse could do. She borrowed him off and on for five months and realized something other would-be owners had not: Cebe was more athletically gifted than any animal Josey had seen. He never lost his bearings and hardly ever bumped a barrel, even at top speed. Just as important, he had fire in his belly. “He wanted to win as much as I did,” she told me. “Before I went into the ring, he would almost stand and look at the other barrel racers and decide how much he wanted to beat them by.”

Reynolds wanted $5,000 for Cebe, but he agreed to settle for $2,500. In a tale that is now told and retold in Martha Josey lore, she cried while admitting to her mother that she’d agreed to buy Cebe but didn’t have the money. Her mother told her she had just sold a mineral lease on their property—for $2,500. Cebe was hers.

Josey describes acquiring Cebe as her Cinderella moment, only the prince of this fairy tale was a gelding with a narrow blaze and two white stockings on one side. “One day I didn’t have anything,” Josey told me, “and then the next day I had this horse that was phenomenal.”

Josey realized that she could correct Cebe’s one-barrel problem by placing an irritating piece of leather in his bit, just under his cheek, to get his attention when he needed to turn toward another barrel. With a ferocity for practice carried over from the basketball court, she would saddle Cebe every day after coming home from the ammunition plant and ride until dark. After she had trained him, many on the rodeo circuit couldn’t even recognize him as the same animal who’d always wanted to call it a night after one barrel.

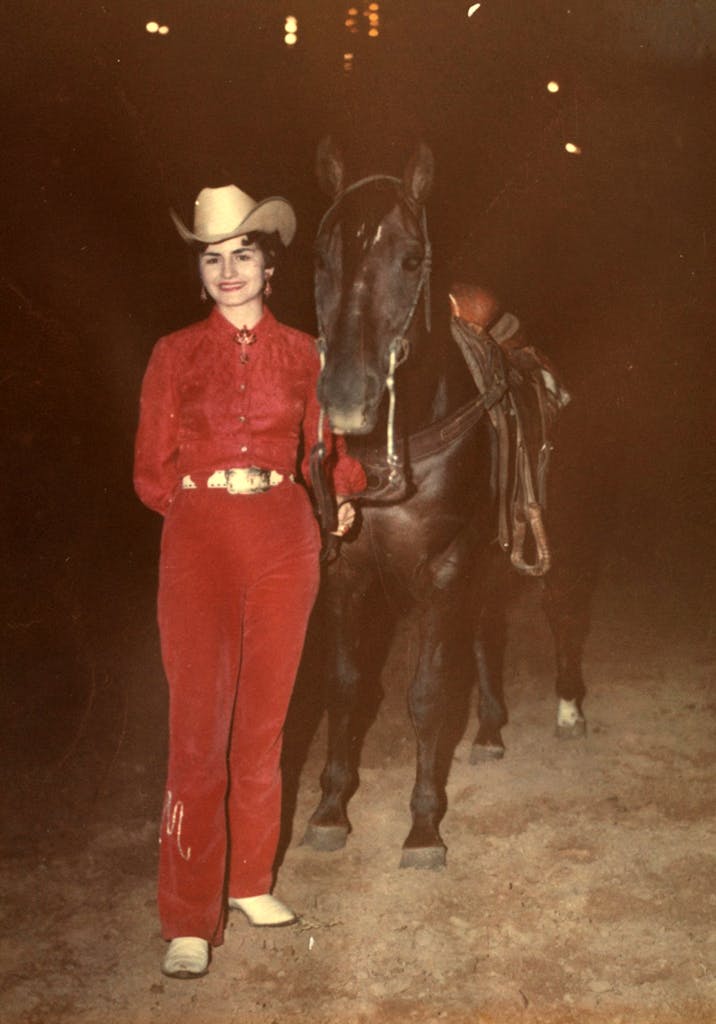

The pair never looked back. By 1964, Josey was the Texas Barrel Racing Association champion. A 1965 story in Quarter Horse Journal noted, “The attractive brunette won the coveted crown by a margin of 1,700 points over her closest rival.” By her count, she and Cebe won 52 races in a row.

The extraordinary winning streak allowed Josey to exercise another natural skill: showmanship. She hired a seamstress from Karnack to custom-tailor her outfits with sparkles and fringe. She once came across an old wedding dress and repurposed it into a lacy, poufy competition shirt. “It was maybe overdone in the eyes of her competitors, but just think what it looked like in the arena,” said photographer Kenneth Springer, who has covered barrel racing since the sixties. “It was glamorous.” Over the course of her career, she became known as the Queen of Sequins. “Martha has always—always—dressed the part, no matter where it was,” Springer added. “It could be in the hottest, dirtiest, most dusty arena, and she’s going to dress like a cowgirl.”

Never one for understatement, Josey soon used a chunk of her rapidly accruing prize money to purchase a new black-and-white Pontiac Bonneville and a matching custom-made horse trailer with a cherry-red interior. One day in 1965, she pulled into the parking lot for a barrel race in Hillsboro, near Waco, when a young calf roper named R. E. Josey saw her get out and unload Cebe. He turned and asked a buddy about the brunette with the chiseled gelding. Today, Martha and R. E. joke that he fell in love at first sight—with Cebe.

At the time, R. E. had a rope burn across his face, which Josey took to be a permanent scar. That night, when he asked her out, she agreed, partly out of pity. Once they began dating, she was pleased to find out the mark had faded. They were quickly smitten and married the following year, moving to R. E.’s hometown of Post, near Lubbock, where he worked in oil fields as a driller and pumper. It wasn’t long before he discovered his new wife was not fond of the kitchen. (This remains true today: one recent Christmas, R. E. decided to hide Josey’s presents in the oven, knowing it had the one door in the house she would never open.)

As a woman who had grown up beneath East Texas’s towering pines, Josey was soon homesick. The plains had too much dust, too much wind, too much unbroken sky. She missed the lacy shade of oaks and evergreens, and she missed her mother, who had inherited her grandmother’s land back near Marshall. She talked R. E. into moving in with her mother and opening a rodeo school. He renovated the sagging barn. They fenced off an arena. Some evenings, he would turn on the car headlights so he and Martha could ride horses long into the night.

The couple opened Josey Ranch in 1967 with a class of 33 students. They charged $100 for room and board plus two weeks of barrel racing and roping instruction. Josey spent most of the first $3,300 to hire a professional photographer to shoot images for brochures and ads. She’d inherited an instinct for promotion from her grandmother Mattie Castleberry, an inventive marketer at a time when few women owned businesses. “She didn’t drink, she didn’t smoke, but she loved being an entertainer,” Josey told me. Her grandmother once coaxed a popular church band to play at one of her dance halls, Mattie’s Ballroom, on a Saturday night. The religious ensemble, concerned about a secular drift, agreed, on the condition that she keep their name off any flyers. Once they had a deal, Mattie drove through the streets of Longview, hanging halfway out of her car with a bullhorn to announce the upcoming gig. Sunday morning, most of the congregation filed into their pews with Mattie’s Ballroom ticket stubs still stapled to their collars.

“Martha comes across as Southern and a little naive,” Springer, the rodeo photographer, observed. “But she is one of the best businesswomen ever.” She’s developed sponsorships with the makers of horse health and nutrition products and ranch equipment, proudly wearing their logos for the cameras as she films product endorsements. A Purina horse feed banner hangs at the entrance to Josey Ranch. She sells her own brand of bits and saddles and attached her name to a now-defunct line of signature Western wear. But most of her success has come from the rodeo school. In the 54 years since it opened, Josey Ranch has hosted tens of thousands of students—Josey puts the number at more than 200,000. These days, when registration opens for her summer camps, parents wait by their computers like fans trying to snag concert tickets. The kids return year after year, and when they grow up, they enroll their own sons and daughters. Many have gone on to their own rodeo fame, including recent world champions Fallon Taylor and Mary Walker. When Josey won the barrel racing world title in 1980, her closest challenger, Lynn McKenzie, was one of her former students.

From the start of her career, Josey was determined to be world champion. When she wasn’t at the ranch teaching, she and R. E. were on the road, winning belt buckles, saddles, horse trailers, and trophies. She made it to the National Finals Rodeo while riding Cebe in 1968 and 1969, but by 1970, he was starting to show his age. She tried other horses, but none could match his ability and drive to scorch the competition. Then one day in March 1978, she and R. E. attended a barrel racing clinic in Hutchinson, Kansas. R. E.—who could scout horses like a coach eyeing quarterbacks—mentioned he liked the looks of one woman’s bay horse. By the time he told Josey, however, the event had ended and the attendees had returned to their motel rooms.

Martha marched up and down the hallways of the motel, knocking on doors, searching unsuccessfully for the owner of the bay. “I was actually sitting in my hotel room,” she recalled. “It was five o’clock in the morning and a truck outside starts up.” She hurried to the parking lot and, in a stroke of luck, found the woman she was looking for. With R. E. still in bed, Josey wrote a check for $7,500 on the spot. This gelding’s name was Sonny Bit o’ Both. She began to train him, and he took her to the national finals four years in a row. The duo won both the American quarter horse championship and the world barrel racing championship in 1980, a twin record that’s never been matched.

Barrel racers typically own one standout horse that makes their careers. Josey owned two champions at the same time and went on to qualify for the national finals on four additional horses over the rest of her career. After Josey began riding Sonny, Cebe lived the rest of his days at Josey Ranch, free to wander as he pleased, like an oversized dog. When he died, at age 25, Josey buried him under a tree she can glimpse from her kitchen window.

Her fame grew after the world championship, and so did demand for her coaching. In 1981, while filming an instructional tape about training inexperienced horses, Josey suffered one of the most debilitating injuries of her career. “I had borrowed a young horse from a friend,” she recalled. “He’d been great for the whole film, but then, all of a sudden, as young horses can do, he started jumping and lunging and bucking.” Josey was thrown off and hit the ground on her side. The impact snapped her pelvis, and when an ambulance arrived to rush her to the hospital in Shreveport, Josey told the EMTs that she couldn’t move her legs. “They said that I’d never walk again and I would definitely never ride again,” she recalled. “They thought I was paralyzed.”

When Josey first returned home, she needed a wheelchair but was determined to resume her career as soon as her pelvis healed. After all, she was the reigning world champion. She exercised daily in the ranch’s swimming pool to regain strength in her legs, while R. E. would lead Sonny into a pond on the property, making him swim to stay in shape, with Josey wheeling along the banks to keep her horse motivated. “She is fearless,” said longtime friend John Adams, a retired physician in Marshall, who saw her after the accident. A few months later, Josey was back on the rodeo circuit. She and Sonny made the finals again in 1981; this time, her ex-pupil McKenzie took the championship.

Josey can think of only one time when she ever felt frightened—and her fear had nothing to do with cracked skulls or busted hip bones. It was during her 1980 pursuit of the world title. She realized she was double booked, registered for two rodeos in one day—one in Oklahoma City and the other 450 miles north in Omaha. R. E. offered to drive a horse to Omaha so that Josey could catch a flight after finishing her race in Oklahoma. He assumed she’d fly commercial. Instead, she called the airport and booked a private twin-engine plane for $2,500. Turbulence rocked the small aircraft throughout the two-hour flight. “I thought I was going to have a nervous breakdown,” she said. Even though she stepped off the plane shaken, she stuck with her look-good-to-ride-good philosophy. (Rare is the soul who has ever seen Josey without full makeup.) Once her feet touched solid ground in Nebraska, she hired a limo for the short ride to the venue.

Starting with the world championship, Josey reached the height of her long career in the eighties. She qualified for four national finals in the decade, was inducted into the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in 1985, and received the honor of a lifetime at the 1988 Winter Olympics. Calgary, as the host city, chose to showcase rodeo alongside other exhibitions in that year’s Olympic Arts Festival as a nod to Southwestern Canada’s equestrian heritage. Josey was selected for Team USA’s barrel racing squad, and in her trademark style, she sized up the proposed uniforms’ simple design and decided they needed more pizzazz. She had her tailor in Texas create red-white-and-blue satin shirts with puffed-up shoulders as big as pineapples, stars down one arm, stripes down the other. The U.S. barrel racing team defeated Canada for the gold Arts medal, and Josey won the bronze in individual competition.

Josey made what she expected to be her last trip to the National Finals Rodeo in 1998. By then, she was sixty and content to focus on her riding clinics and students rather than the pursuit of championships. But, in 2003, she met Red Man Bay. He was one of the finest competitors she had seen in years, hardly ever touching a barrel as he drew high-speed clovers in the soil beneath his feet. With Red Man Bay, Josey believed she could earn one more trip to the national finals, 46 years after she and Cebe first qualified.

Then came that night in Austin in 2004—the accident. As she lay in the hospital, her pelvis broken for a second time, her friend Deb Brown helped answer calls from all over the world, as news spread through the tight-knit rodeo community. Josey’s doctors told her she was lucky to be alive and recommended that she take a year or two off. But she was no stranger to dire predictions. Meanwhile, Brown overheard R. E. on the phone, telling a friend, “I think she’s got a cracked skull, and her hip may be broken. She’s got some good old bruises, and her wrist is pretty bad. But other than that, she’s doing pretty good!”

“I will never forget that as long as I live,” Brown said. “That’s the Josey way: never quit.”

After three weeks in the hospital, Josey was scheduled to be discharged, but she still wasn’t strong enough to sit up on her own. Her brother and nephew came up with a solution: they picked her up in a motor home that allowed Josey to lie down as they drove back to the ranch. At home, she slept in a hospital bed for a couple of months. R. E. got her out of bed each day and drove her to Marshall to rehabilitate her at the hospital’s pool. Before long, she added an hour on the treadmill to her routine.

In June, just three months after fearing that his wife wouldn’t live through the night, R. E. helped Josey climb back onto Red Man Bay. “I felt like I was home,” she said. She was well enough to return to competition at the end of that month, and she placed seventh at the barrel race in Colorado’s Greeley Stampede. “I started going to every rodeo that I could,” Josey recalled, but she also became aware that Red Man Bay had yet to fully recover from his injuries. He had been through rehab, but she could feel he was still sore. After a race in Cheyenne, Wyoming, a few months later, “I realized that trying for the national finals would be too hard on my horse.”

As the years passed, she competed on different horses here and there but found that the crash in Austin had robbed something from her. She noticed herself entering fewer and fewer races, and she never attempted to make another national finals.

Growing up in Marshall, I knew of Martha Josey. It was hard not to, since the local paper dutifully covered her career milestones, and every drive to Caddo Lake would take my family past the white gate to Josey Ranch on Texas Highway 43. In the summer of 2013, some cousins from St. Louis visited, and I took them to the Mesquite Championship Rodeo, outside Dallas. Before the barrel race began, I gave them a brief tutorial on the sport, and with a surge of hometown pride, I mentioned that a legendary racer named Martha Josey was from Marshall. I wondered aloud what had become of her, realizing that she must have been well into her seventies by then. After the first few women in line made their runs, the name of the next contestant came over the loudspeaker. It was Martha Josey.

Today, her camps and clinics remain as popular as ever. When Josey teaches barrel racing, the bonds she forms with students and their families fulfill her now in the way world championships once did. The honors are still adding up—in 2020 she was named to the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame, a pinnacle of recognition unavailable to women before 2017—but her greatest pride comes from shaping the winners of tomorrow.

When I visited Josey Ranch for a recent weekend session, she told me she can spot the girls who’ll succeed. Talent and ability aren’t the only signs of a future winner—desire is the key. “To be a champion, you’ve got to think like a champion,” she said. “You’ve got to act like a champion.” And the young girls who flock to Josey’s classes continue to idolize her. “It actually is kind of scary meeting a legend,” said eleven-year-old Madyson Mansel, whose mother came to Josey Ranch in her youth. Twelve-year-old Bergan Yazzie told me she felt butterflies in her stomach when she first met Josey. Now that Yazzie has attended thirteen camps, though, she’s managed to absorb some of her teacher’s inextinguishable confidence. “Once you come here,” she said, “you cannot stop coming back.” By the end of this weekend, Yazzie had beaten the competition to win a new Martha Josey Circle Y saddle. Josey also presented the shyly smiling student with one of her old competition shirts, a green-and-gold number with long fringe and, naturally, sequins.

Josey turns 83 in March, and she still rides every day. The thought of retirement has never crossed her mind. “She’s never quit in her life,” Mansel said. “She’s the star that will never go away.”

Cedar Hill journalist Laura Beil, a former Dallas Morning News medical reporter, has written for numerous publications, including Men’s Health, the New York Times, and Cosmopolitan. She wrote about the stem cell industry for Texas Monthly’s January 2020 issue.

This article originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Not Her Last Rodeo.” Subscribe today.