This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There are 21 steps between Carl Lewis and the lip of the long jumper’s pit. The first is preceded by a profound stillness. Lewis sets his left foot forward lightly, with the heel raised, like a ballet dancer, and then he stares at the track in front of him, his muscular shoulders unflexing as he lets his arms swing free at his sides. Or perhaps his eyes are closed. It’s hard to tell, for he can stand in such a position for a minute or more. There is no nervous fidgeting, no movement of the head or clenching of fists; his face is as placid as that of a Zen master, his body as relaxed as that of a lifeguard on a lazy afternoon. Crowds grow quiet, almost instinctively, when Lewis toes the line, as though they expect something that has never been seen before.

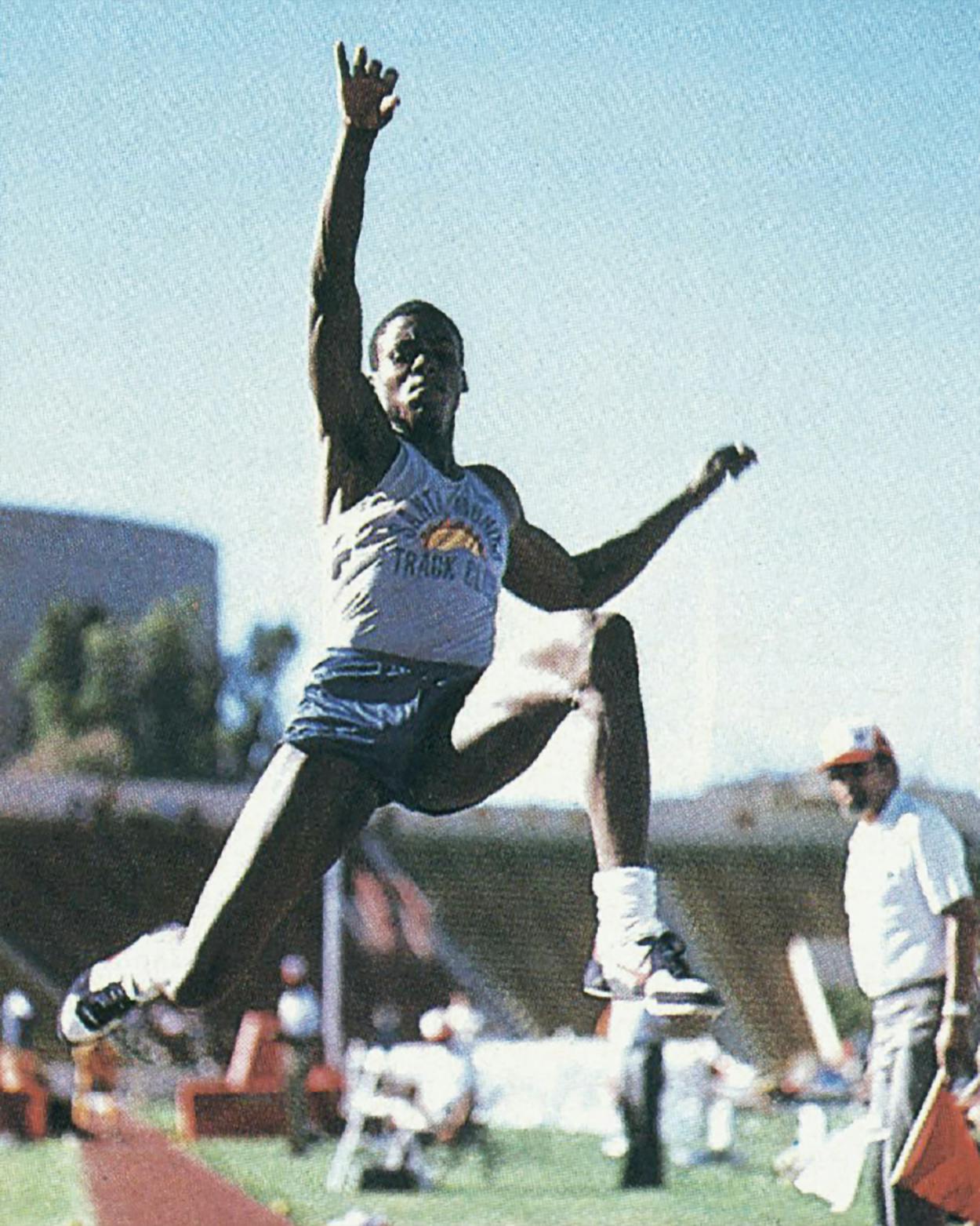

And then, so quickly and smoothly that you can never be certain just when he made up his mind to begin, he rocks back on his right foot and takes the first high, prancing stride. The initial three or four steps are measured and relatively slow, but now his head is up and his eyes are riveted on some point just above the horizon that only he can see. After ten steps he is running faster than most men have ever run in their lives, and yet he has reached that speed so effortlessly that it is scarcely noticeable. As the strides grow longer and the knees pump higher, he maintains the same outward composure, the same even and fluid motion. At eight strides from the board, he already knows whether he will hit it on the money. When he was younger he had to make last-minute adjustments—for overstriding, for extra adrenaline, for momentary lapses in his concentration—which meant that he shortened or lengthened his stride at this point. But now he feels that line ahead, and nine out of ten times he can leave the ground within one inch of it. Just before he hits the board, his strides are nearly eight feet long, his speed almost 27 miles an hour. The 21st step is a little shorter so that he can plant his right foot, give a slight flex to the knee, and launch. Yet these motions are too fast to be visible except to the slow-motion camera: the body doesn’t jerk upward, nor is there a loud sound when his right foot hits the board. Rather he appears to be running through the pit, yet upward into space, like a sleek 707 lifting off the runway.

Now, perhaps, his expression will alter, if only slightly, if only to purse his lips or furrow his brow. He doesn’t do this from fear; he got over the fear years ago. The temporary feeling of weightlessness, the fleeting terror of tumbling forward with such force that he lands on his head—these are no longer unfamiliar sensations. That look on his face is more likely an involuntary expression of his one earnest desire: to jump farther and run faster than any man has ever jumped or run.

The first time I saw Carl Lewis jump was on a humid, oppressive afternoon this spring at the University of Houston stadium. At the time he was nineteen years old, closing in on two world records (in the 100-meter dash and the long jump), and, at least for the time being, the world’s most celebrated track-and-field athlete. Everywhere he went he was being compared to Jesse Owens, the last black athlete to show such world-class versatility. And on this day, a week before he would try to equal Owens’s longest-standing record (of winning both a track and a field event at the NCAA Championships), Lewis had agreed to show me a few secrets of long-jump technique.

Of course, Carl Lewis’s newfound fame had very little to do with the long jump. Those who knew his name at all knew him as the latest candidate for the title of “world’s fastest human,” a distinction held for the past thirteen years by another Houstonian, Jim Hines, and before that by ex-Dallas Cowboy Bob Hayes. Track and field usually attracts the attention of the public only once every four years—at the Olympic Games—but people reserve a special fascination for truly great sprinters. That’s what made Lewis’s attitude all the more astonishing: he had indicated that he might give up sprinting altogether if it ever interfered with his ability to long-jump. “Everybody asks me about my sprinting,” he said, “because, I guess, that’s more glamorous. But long jumping is the more interesting and complicated event; it’s more of a challenge. If I’m able to jump and sprint at the same time, then I’ll do it. But as soon as sprinting starts to hurt my jumping, there’s no question which one I’ll choose.”

He had arrived at the stadium with his older brother Mackie, whose competitive days as a sprinter and long jumper are over but who also attends the university and shares an apartment with Carl. Mackie began marking off Carl’s runway with a tape measure and chalk while Carl answered questions for a local sports reporter who had shown up with a mini-cam and a microphone. Sample question: “How does it feel to be compared to Jesse Owens?” Answer: “Jesse Owens was in a class by himself; it’s great even to be mentioned in the same breath with him.” (Answers like that have endeared Carl Lewis to the press; Carl is so well-mannered that he won’t even criticize last summer’s Olympic boycott, which may have cost him at least two medals.)

Interview over, Carl was ready to work. “This is Thursday,” he said, “which is the day I work on my approach. By this time of the year, it should be perfect.”

We started walking down the runway, which Mackie had carefully marked with three checks: one at the point where Carl starts, one eight strides from the board, and one four strides from the board. “I begin my run,” said Carl, “at 147 feet 6 inches, which is the longest I’ve ever run. I worked out with weights a lot in the off-season to lengthen my stride. Now, the only mark you have to watch is the one four steps from the pit. If I hit that mark with my toe, it’s a great jump. If I don’t, it’s a foul or a short jump. There’s nothing you can do after that point.”

I stopped at the predetermined mark and watched while Carl readied himself for the first run. He wiped the sweat from his forehead, placed his foot on the mark and waited for that moment of maximun concentration that comes instinctively to all great athletes. Then he took off at the same speed and with the same accelerating cadence that he would use a week later at the NCAA Championships in Baton Rouge. I stared directly at the track and saw his right toe hit one-half inch behind the line. Carl made only a halfhearted jump (he saves his energy for competition) and ran on about twenty feet past the pit. Mackie signaled “okay” to his brother. “That felt just right,” said Carl. “If I do that again, let’s go home.”

He did, in fact, hit the mark perfectly three out of four times (the fourth was missed by an unacceptable four inches), which gave us plenty of time to talk about Carl’s favorite topic: the art, science, beauty, and natural history of the world’s greatest sporting event, the long jump.

Carl will understand if you’re skeptical at first. Of all track-and-field events, the long jump seems the least complex, the least demanding, and ultimately the least interesting. There is no bar to clear, no tape to break, no clock to beat. There is no paraphernalia to master, like the perfect spin on a discus or the powerful arc of the hammer throw. The event has fostered no dramatic innovations, at least none to compare to the so-called Borzov style of sprinting, the fiberglass pole for pole vaulting, or, in the high jump, the Fosbury flop. The drama of the event is entirely dependent on the quality of the entrants: let’s line ’em up and see who can jump the farthest. And there has been, until recently, no chance of seeing the world record broken in the long jump. Ever since Bob Beamon of the University of Texas at El Paso jumped 29 feet 2½ inches at Mexico City—about the width of an average residential street and almost 2 feet farther than the prevailing record of 27 feet 4¾ inches—the establishment of a new record has seemed like so much science fiction. Who wants to watch an athlete who consistently achieves the second-longest jump in history?

But all of that began to change earlier this year, when Carl Lewis came out of nowhere at the Southwest Conference Indoor Championships in Fort Worth to make the best jump of his life and the fourth-best in history. At 27 feet 10¼ inches, it was a new indoor record. (All long jumpers insist that they can jump farther outdoors, although there is no law of physics that makes this probable.) Then, as a “diversion,” Lewis entered the 60-yard dash as well, and he won it in the remarkable time of 6.06 seconds. He stumbled at the start but still came within two hundredths of a second of tying the world record in that event. There were only 5765 people on hand for the performance, but news travels fast in the track world. Three weeks later Lewis was the toast of the NCAA Indoor Championships in Detroit, where he won both the 60-yard dash (despite a poor start) and the long jump (despite fouling on his first two jumps) and came within three-eighths inch of breaking the world record he had just set in Fort Worth.

At the age of nineteen, Lewis within the space of two months created an excitement unmatched since . . . well, since that day in 1935 when a 21-year-old named Jesse Owens set three world records and tied a fourth at the Big Ten Championships. Sooner or later it had to happen: Lewis would put it all together and challenge both Bob Beamon and sprinter Jim Hines, the two men whose 1968 records had rarely been approached since they were set and never at sea level. All eyes were pointed toward the NCAA Championships in Baton Rouge, where Lewis would face the stiffest competition so far in the 100-meter dash, and then the USA Track and Field Championships in Sacramento two weeks later, where he would face long jumper Larry Myricks, an alumnus of Mississippi State, who had beaten him on eight previous occasions. Again the name of Jesse Owens was invoked: he was the last man to win both events at both tournaments (in 1936).

It was early morning on a sultry June day in Baton Rouge, the kind of day when the steam rises off the Mississippi and the spreading oaks hang limp in the deadness and the humidity. It was not a day for setting records, but at least it wasn’t raining. I said as much to Tom Tellez, who had just ordered breakfast at the Prince Murat Motor Inn, but he responded circumspectly. “With the long jump you can never tell,” he said. “I believe that a world-class long jumper can set a new record at any given time. Atmospheric conditions are only a small part of it.”

If Tom Tellez says it, it must be true, for Tellez is widely recognized as one of the two or three best jumping coaches in the nation. He is the sole reason Carl Lewis decided to attend the University of Houston, and he is perhaps the only man who could have persuaded Lewis to change his jumping style completely just a few months after he had broken the world record for his age group. Now that all their work was finally paying off, I asked Tellez to tell me just how he had turned such a simple act as jumping into a coachable science.

“First of all,” he said, “track and field is all science. Every movement in every event must conform to certain biomechanical laws governing acceleration, inertia, center of gravity, and so forth, and the long jump is no exception. But traditionally the long jump has been something the coach didn’t work on as much. He just took his kids and said, ‘Go over there and jump,’ and the best one was entered in the meets. Now, I proceed from the assumption that there is a perfect scientific model for every event, and the athlete must adhere to that model. Not because I say it, but because Newton and Galileo say it.

“At first Carl resisted this a little; his first year of college he was caught between what he felt and what I was teaching. He was like a wild stallion. All we did was take all that energy and channel it into a system. Don’t give me credit, though, for an athlete like Carl. Great athletes have naturally intelligent bodies; Carl’s body is a genius.”

The near-perfect model for the long jump went on display later that day when 24 competitors started warming up at Bernie Moore Track Stadium before a mere handful of spectators. As usual, the qualifying for the field events was held in the afternoon, with the trials in the sprint and distance events scheduled for the prime-time crowd that night. In the long jump the trials would whittle the field down to twelve finalists; in the 100 meters, to nine. Lewis was scheduled to jump fourth, and he had already decided to make this a conservative try. If at all possible, he wanted to quit after only one jump, thereby giving himself at least two hours before his first qualifying run in the 100-meter dash.

The first jumper stepped over the line, and the pit judge raised his black flag, signaling a foul. He was followed by Britt Courville of Texas Southern, who got off a jump of 24 feet 2¼ inches, and Jason Grimes of the University of Tennessee, who sailed 23 feet 7½ inches. If these jumps were any indication of the quality of the rest of the field, then Lewis wouldn’t have to strain himself to qualify among the top twelve.

He stared at the ground, hands on knees, for about 15 seconds after the green timing light was turned on. Then he stood stock-still for another 45 seconds, looking off into the middle distance. And finally he started his approach run. It was very conservative, calculated to end a few inches behind the line so as to run no risk of fouling. He windmilled through the air, arms and legs both pumping in the so-called double hitch-kick style that is now his trademark, and landed exactly 26 feet 8½ inches into the pit. It was good enough and he knew it. It was his last jump of the day. He simply passed on the next two rounds, and two hours later, when all the jumping was finished, he led the field and held a new stadium record.

More troublesome was the 100-meter qualifying, which featured one of the strongest fields in recent years. Lewis would have no trouble qualifying, of course, and he had competed against most of the sprinters in Detroit, but this would be the first time he would face them at the full 100-meter distance instead of the indoor distance of 60 yards. The results were predictable. The first heat was won by Calvin Smith of the University of Alabama, who had been favored to win at Detroit but pulled a muscle during trials. The second heat went to Jeffrey Phillips of the University of Tennessee, the crowd favorite and, it turned out, the only white man to reach the finals. (The fans in my section made it clear that he was the favorite because he was white.) The third heat was won by Mel Lattany of Georgia; he had been nipped at the tape by Lewis in Detroit and was the defending champion. Lewis ran hard against a slight wind and won his heat, too, but with a fairly slow time of 10.34 seconds. “Don’t worry about that,” said Mackie when I saw him later. “He just runs as fast as he needs to.”

And thus, rather anticlimactically, the first day of the quest for Jesse Owens’s NCAA record came to a close.

At the original Olympic Games of ancient Greece, there were only three field events. Two of them—the discus and the javelin—were clearly derived from the science of warfare. The long jump is harder to explain. My own theory is that jumping entails something very visceral and close to the source of all competitive instinct. Except for fighting, the crudest form of physical contest, and racing, the simplest, the impulse to prove which of two men can jump farthest is probably the most basic of sports. It has the added advantage of being the only one of the three field events that comes more or less naturally to the athlete.

The Greeks were fascinated by athletic competition but wholly unconcerned with record keeping. (In fact, striving toward some abstract record instead of merely competing against other athletes is a practice peculiar to the twentieth century.) Hence all we know of the Greek long jumpers is that one Phayllus was the best of them, having jumped so far that he broke a leg. Ancient records would be of no use anyway, since the Greeks were allowed to carry large stones in each hand. By swinging their arms on takeoff, they could gain far greater distances than the average modern jumper. (By way of comparison, in 1854 a British performer who gave long-jump demonstrations with five-pound dumbbells in each hand managed to jump 29 feet 7 inches.)

Organized competitive long jumping was not restored until 1860, at the Grand Annual Games at Oxford, and long jumping as we know it did not begin until the advent of the sport’s first and only technical innovation: a rigid takeoff board, introduced at the AAU Championships of 1886. The most remarkable thing about the intervening 95 years is that they have been so unremarkable. If by some miracle we were to view a film of that 1886 meet, we would find the technique of the pole vaulters and high jumpers almost comical by today’s standards, but the long jumpers would look very much like modern athletes. Much has been made of the fact that Carl Lewis uses a double hitch-kick while suspended in air during his jump, but in fact there is an extant picture of a Syracuse University jumper named Myer Prinstein who was using the same motion in 1898. When I mentioned this to Tellez, he was totally unsurprised. “Scientists and coaches don’t invent the best techniques,” he said. “Great athletes discover them.”

The only rational explanation for the unspectacular records of Victorian long jumpers, who strove toward the “24-foot barrier” accessible even to high school athletes today, is that there weren’t many of them. Most athletics, but especially track and field, were limited primarily to the privileged leisure classes of England, Ireland, and New England, and among these gentlemen, records counted for very little. (The winner of the 1896 Olympics, Ellery Clark of Harvard, learned to long-jump by practicing aboard ship on the way to Athens.)

But the whole character of the event began to change in the twenties. One reason was the extremely rapid growth of universities after World War I, and hence the greater number of young athletes. But probably more important was the advent of the black athlete. At first the blacks were limited to universities in the Northeast, and to certain meets even then, but they were tolerated in track and field long before they were able to compete in team sports like football and baseball. And it was in the long jump that a black athlete first won an international victory, at the Paris Olympics of 1924. DeHart Hubbard of the University of Michigan was the gold medalist but received less notice than he might have. The reason is that Robert Le Gendre, a Georgetown University student who had never even jumped 24 feet before, suddenly soared 25 feet 5¾ inches for a new world record. He was competing not in the long jump but in the pentathlon. The following year Hubbard beat that mark with a leap of 25 feet 10⅞ inches. In less than a year almost 8 inches had been added to the world record.

The twenties were also the age of great experimentation, and for a while there was a great debate as to whether the hang style, the float style, or the hitch-kick style of jumping was best. The first is the method most natural to beginning jumpers and involves simply holding the legs up until the last possible moment, in a manner that makes the jumper appear to hang in space for a moment before his impact with the sand. It was believed for years that if the stomach muscles could be strengthened enough, a jumper could achieve this effect without falling backward. This theory has since been proved to be hokum. The float style is similar to the hang but requires the jumper to keep his legs straight and follow them into the pit—literally head over heels—in such a way as to fall forward on impact; the method gets its name from the way it looks in the air. The hitch-kick style, the least preferred of the three to this day, involves a rotating motion with the legs and arms so as to bring the body totally upright during the jump. This causes the jumper’s legs to move upward and is believed to provide more control after landing. With only minor variations, these remain the only styles of jumping in use.

Much of this debate was rendered moot on May 25, 1935. That was the day that Jesse Owens, a sophomore at Ohio State University, jumped 26 feet 8¼ inches in a meet at Ann Arbor, Michigan, to better the world record by more than 6 inches. The significance of that record was not immediately realized, because he set two more world records the same day—in the 220-yard low hurdles and the 220-yard dash—and tied the record for the 100-yard dash. (Carl Lewis’s coaches name these as his best four events—substituting the 110-meter hurdles for the obsolete 220 lows—as well, and they believe he could become a world-class competitor in any of them.) The long-jump record, however, was the one that stayed on the books longest—an amazing 25 years. It was slowly beginning to dawn on track coaches that long jumping—whether float, hang, or hitch-kick—was inextricably linked to speed.

DeHart Hubbard, Jesse Owens, and Bob Beamon—each the best jumper of his day—never had the advantages of modern coaching, sports medicine, and scientific research to aid their performances, but they puzzled the track-and-field theoreticians for years. How can a man suddenly soar six inches, eight inches, or—in Beamon’s case—nearly two feet beyond the world record and yet never be able to duplicate the feat? Leaps in achievement like that are characteristic of new sports or sports affected by technology, but not of events that have been unchanged for almost a hundred years. Last year a West German track-and-field magazine calculated the hundredth-best performance in each event, then showed how recently that performance would have rated as a world record. Thus 1980’s hundredth-best performance in the pole vault would have been a world record as recently as 1964, indicating the rapid improvement in equipment and technique in that event, whereas the hundredth-best long jumper would have been a world champion in 1924, longer ago than for any of the nineteen events studied.

What these statistics suggest is that until very recently the theoretical principles of long jumping had not been understood, at least not by the great majority of track coaches. Hours are spent on perfecting pole vault, hammer throw, and javelin techniques, whereas long jumping is still regarded as a God-given talent: you either have it or you don’t.

“That’s the way I used to feel, too,” Tellez told me. “For my first six years as a coach, I thought I knew everything there was to know about field events. Then I discovered Geoffrey Dyson.”

Geoffrey Dyson is a British coach and theorist who in 1962 published a book called The Mechanics of Athletics. Now considered a classic by a certain school of coaches, it was the first major application of applied physics to the techniques used in track-and-field events. Tellez discovered the book while coaching at the University of California at Fullerton. He devoured it, read and reread it, and even began to review his college physics textbooks to further refine his appreciation of the principles involved in running, throwing, and jumping.

“It seems so obvious now,” he said, “that we should look to physics for our ideal models, but at the time it had not occurred to me. In the long jump, for example, all the attention had been on the technique while the athlete was in the air. This is the least important part of the technique. Everything important happens before that, during the approach; once the athlete leaves the board there is nothing he can do to change the parabola of flight. So all motion in the air has one purpose and one purpose only: to land correctly.”

On the day Tellez made that discovery, Carl Lewis was one year old.

The night after Carl Lewis qualified for the long jump and sprints, the rains began, steady, tropical downpours that pounded on the streets throughout the night and then continued fitfully for most of the following day. There was still a light sprinkle when Lewis arrived at the stadium, ready for the long-jump finals, but the judges dawdled and delayed while trying to decide whether it was safe to jump from the wet runway. Lewis jogged up and down to stay loose, kept his sweat suit fastened securely against the elements, but showed no visible emotion. The day he was supposed to match Jesse Owens’s record, and now this had to happen. He looked up into the stands—there were only a dozen or so people waiting in the rain—and searched for the faces of his father and mother. They had come all the way from Willingboro, New Jersey, to be here for the event. He remembered the time, when he was only a tyke, that he had actually met Jesse Owens, when he had walked up and shaken his hand. His father had arranged it all.

Finally the judges made up their minds; as much as they wanted to give Carl Lewis a chance at setting an NCAA record that day, they couldn’t risk an injury on the wet track. The public address announcer informed the crowd that the long-jump finals would be held in the LSU field house, which meant that no jumps would count toward records. As Lewis started toward the field house, he picked out his father and mother, walking with Mackie and Tom Tellez, and he knew that they’d gotten there on time after all.

It’s impossible to talk about Carl Lewis without talking about heredity. William McKinley Lewis, Jr., Carl’s father, was a football star and an excellent sprinter and long jumper at Tuskegee Institute in the late forties, and his mother, Evelyn Lawler Lewis, was a hurdler who represented the U.S. at the Pan American Games in 1951. The two of them have been the only two track-and-field coaches in the city of Willingboro, New Jersey, since 1963—he at John F. Kennedy High, she at Willingboro High. Her teams win more often. They have two children besides Mackie and Carl: 25-year-old Cleve, the first American black ever to play pro soccer, and 18-year-old Carol. Carol holds the American long-jump record for junior women, made the U.S. Olympic team while still a junior in high school, and is entering the University of Houston this fall with a reputation as one of the most gifted female athletes in history.

“There is more to it than physics,” said Tellez. “But the most important thing about Carl’s family background, I think, is the stability it provides. When you have that kind of support and closeness, you can achieve the kind of total concentration, the kind of single-mindedness, that it takes to be a champion.” Ghetto kids achieve that, too, but it happens much less often. Jesse Owens and Bob Beamon had that much in common with Carl Lewis: they came from very stable family backgrounds, had a strong sense of who they were (both were deeply religious and patriotic), and wore their fame very lightly. Since Mexico City was one of the most politically charged Olympiads—symbolized by the black power salutes of sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the victory stand—it’s easy to forget what Bob Beamon did after his stunning 29-foot jump. He fell to his knees and prayed.

“I’ll never forget,” said Carl, “that when I competed in the AAU nationals one year in high school—it was in L.A. that year—Bob Beamon came out to see me. We had a nice long talk, and he was there to encourage me. I was jumping pretty good at the time, and he just said to remember how well I’m doing now for when the time comes that I’m not jumping so well. He tried to tell me how to take all the publicity and the attention in stride, and I really appreciated his doing that for me.”

No records would be set today. The rain, the shift from outdoors to indoors, the relative weakness of the field, meant that Carl Lewis would probably be jumping against himself. Nevertheless, some 150 people made the walk from the stadium to the field house and crowded onto roll-out bleachers just to see him jump. As the delay lengthened—they were now an hour past the scheduled starting time—the pressure on Carl intensified. Not only did he have to win the long jump but he had to run the semifinals and the finals of the 100-meter dash that night. Both were less than two hours away, and he knew that if he had to jump the full six times, he might not have enough left for the sprints.

At last the indoor pit had been prepared, the automatic timing and measuring devices had been erected, and the signal was given for the first jumper. As it happened, that was Gilbert Smith of the University of Texas at Arlington, who was widely considered to be the second-best jumper at the meet. A classic hang-style jumper, with a little shorter approach than Lewis, Smith launched weakly on his first try and recorded only 24 feet 6 inches. Then came a foul, a negligible jump, a respectable 24 feet 9¼ inches by Willie Ross of the University of Michigan, and it was Carl’s turn.

He desperately wanted this to be his first, last, and only jump of the day, and so he thought about it a long time—uncharacteristically long, even for him. He had used up all of the green light and most of the amber—perhaps eighty of the allotted ninety seconds—before he started his run. He hit the board right on target but was startled when it gave under the weight of his body (indoor runways don’t use wood; the board is just a white line painted across the Tartan track). So he fell backward when he landed, spoiling an otherwise good jump. (He couldn’t have known it at the time, but the 26-foot-1-inch jump would be good enough to win, just barely, anyway.) He jumped up quickly, pulled on his sweat pants, and signaled to Tellez to come down out of the stands. They discussed for a few moments what could be done about the board—nothing—and then whether he should pass or take another jump. Lewis decided to jump again—nobody quits after an aborted landing like that—and so he trotted back to his place in line.

When it was Carl’s turn again, he didn’t have any trouble getting mentally prepared. He stood at his starting mark for no more than twenty seconds before rocking back on his left leg and striding with his right.

If it had been possible to watch the jump in slow motion, this is what you would have seen: He begins at about half the speed he can attain when charging out of the starting blocks, but he builds quickly until, by increasing his velocity at a uniform rate per stride, he reaches about 95 per cent of the speed he can attain in a sprint. Since a sprinter achieves maximum speed somewhere between 50 and 60 meters, Lewis could conceivably start his run at, say, 180 feet instead of 147 and attempt to leave the runway at maximum velocity. As a practical matter, it is impossible to jump at 100 per cent velocity, because some energy must be expended in upward thrust, causing a slight slowing just before the takeoff. For another thing, the longer a long jumper runs, the more difficult it is to retain complete control and hit the board with any accuracy. As he gathers speed for the takeoff, Lewis is thinking one thing: “Hit the board.” He doesn’t look at the track; that would slow him down. He has to feel the board in front of him.

The ultimate stride is slightly shorter than the others; he is gathering strength for the upward thrust. He hits the board with his right foot and, keeping the knee slightly bent, propels his body up and out at a 25-degree angle to the ground. This is the optimum angle, so that the thrust outward is approximately two times greater than the thrust upward, a principle of long jumping accepted today by almost everyone, including the Russians and East Germans.

Now comes the most dangerous part of the whole process. Unless Lewis makes some kind of compensation, his upper body will rotate forward very rapidly and flip him onto his head. All movement in the air, in fact, is an effort to correct this rotation, which is caused at the moment of takeoff when the right foot momentarily stops to push upward while the upper body continues forward rapidly. When that happens, the whole body tries to rotate around its center of gravity. Besides being dangerous, the force tends to put the jumper’s feet in the one place he doesn’t want them—behind his center of gravity. So, to compensate, Lewis creates four secondary axes of rotation (his arms and legs), which push him in the opposite direction until the body is brought back upright and the legs are moving forward again. Lewis is able to get enough distance and height to complete two full rotations, or hitch-kicks, before landing. Geoffrey Dyson estimates that a person who could execute three hitch-kicks could add even more inches to the jump.

And the reason becomes apparent shortly. Just before he strikes the ground, Lewis is in a sitting position, with his legs thrust far out in front of him and the seat of his pants not far from the ground. His arms, however, are thrust backward in the opposite direction. As soon as his heels touch the sand, he digs in with all his might and jerks both arms forward simultaneously, creating the curious phenomenon of temporarily throwing his body’s center of gravity out of his body to a point about six inches in front of his stomach. If his timing is right, the force of this thrust will jerk his body forward before his pants hit the sand, and he will have added three or four inches to the jump simply by the way he landed. If his in-air movements are executed correctly, Lewis never actually sees the sand in the pit; he is so high that his eyes look beyond the pit, usually into a covey of photographers’ lenses and TV cameras.

After Lewis did land, there was a moment of suspense as the crowd looked back at the judge—not uncommon, since Lewis comes within a fraction of an inch of the foul line. But the judge held the white flag aloft, and the fans erupted in cheers. It was not a historic jump, but it was one of the few times you’ll see anyone jump 27 feet. The official reading was 27 feet ¾ inch. After that the stands thinned out quickly. Everyone knew that Carl Lewis would pass on his next four chances.

The 1968 UPI picture of Bob Beamon has been reproduced dozens of times but still astounds me whenever I see it. The photographer has captured Beamon at the apex of one of his jumps. His legs are bent at the knee but raised upward and outward at odd angles, as though he just fell off a building. His lanky, toothpick arms are thrust down between his legs, like a circus clown walking on his hands. His mouth is gaping so wide open that he must be making some kind of loud noise. And his eyes are directed not at the sand pit but somewhere to his right, as though he has no idea where he is going to land. This man is, of course, the greatest long jumper the sport has ever known.

There is no reason that Carl Lewis should ever have looked at the videotape of Beamon’s record jump. There is nothing to learn from it. Much of the jump, according to long-jump theoreticians, is bad form. The landing is terrible. Beamon, in fact, was the kind of jumper that coaching purists dislike intensely. Beamon was so inconsistent that he never even knew whether he was going to take off with the left or the right foot. Two out of three times he would miss the board altogether and foul. He usually used an approach run of about 134 feet—very short for world-class athletes—but to set two world records prior to the 1968 Olympics, he shortened it to 114. As a high school athlete in New York City, he didn’t work on his jumping at all; he would have preferred to play basketball. And the jump at Mexico City was 2 feet longer than he had ever jumped in his life and 2 feet longer than he would ever jump again.

Yet Carl Lewis has studied the tape of Beamon’s world-record jump time after time. It happened at 3:46 p.m. on the muggy afternoon of October 18, 1968, just before a torrential rainstorm. In the qualifying the day before, Beamon had fouled twice. As usual, the spectators weren’t even watching the long-jump pit because runners were getting into their blocks for the 400-meter dash. Beamon’s gangling, 160-pound frame loped down the runway, hands and arms flapping as usual, and lifted off on a trajectory that he described later as feeling “just like a regular jump.” Sitting on the bench, watching as he left the ground, were the three men regarded at that time as the greatest jumpers in the world: Lynn Davies, the English gold medalist in the 1964 Olympics; Ralph Boston, the American who broke Jesse Owens’s record after it had stood for 25 years; and Igor Ter-Ovanesyan, the great Soviet theoretician who had battled Boston for eight years and currently shared the world record with him. Watching from the press box was Jesse Owens himself. When Beamon landed, Ter-Ovanesyan turned to Davies and Boston and said, “Compared to that jump, the rest of us are children.”

It was so far that for a few long moments no one was able to convert it from meters to feet. Beamon didn’t realize what he had done until Boston ran over and told him—and Beamon collapsed on the track and prayed.

Thanks to the wonders of videotape and modern science, that jump will be debated as long as it remains a world record. Was it a fluke, caused by the most favorable atmospheric conditions and the chance timing of an erratic athlete, or was it a genuine feat of human strength and agility that would have occurred in any atmosphere and at any time? Without a doubt, the high altitude of Mexico City (7347 feet above sea level) was a contributing factor, but how much is hard to tell. Sports Illustrated commissioned a professor of applied science to evaluate all the variables affecting Beamon’s jump—altitude, temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, air density, and gravitational pull—and his findings were that no more than eleven inches of the jump could be accounted for by the environment. Beamon had still broken the world record by almost a foot, and to this day no one has bettered even the altitude-adjusted figure.

But that’s what Tom Tellez and Carl Lewis set out to do when Lewis arrived at the University of Houston in the fall of 1979. Lewis was the best natural jumper for his age in history. Tellez was widely regarded as the best long-jump theorist. Lewis had spent much of his high school career in great pain, caused by a common jumper’s ailment called patella tendinitis, or inflammation of the knee. At one point it was so bad that he started jumping off his left leg instead of his right (and still set an American junior record). Tellez diagnosed his problem quickly: he was not bending his leg at takeoff to cushion the impact of hitting the board. “If we hadn’t changed that right away,” said Tellez, “Carl’s jumping career might have been very short-lived.” And while he was at it, Tellez lengthened Lewis’s approach (“We’re up to twenty-one strides now, but I’d like it to be twenty-two or twenty-three”) and changed him from a hang-style to a hitch-kick jumper. It takes a fair amount of self-confidence to tell the best jumper in America that he’s doing things the wrong way, but Tellez did it. “You can argue with me all you want,” he said, “but you can’t argue with Newton and Galileo.” Carl agreed to make the changes, and almost coincidentally, they made him a better sprinter as well.

In the closing minutes of the long-jump competition, Gilbert Smith of UT-Arlington made a nice gesture. After five jumps, he was still second to Lewis and would have to jump a full foot better than the best jump of his life to beat him. Rather than take the sixth jump, he gave a wave of his arm, as if to say, “We all know who’s going to win here,” and passed his final attempt. Lewis was the winner after taking only two jumps.

It was fortunate for Lewis that Smith did pass, because that gave him just enough time to jog directly over to the outdoor stadium—the rain had temporarily subsided—for the semifinals in the 100 meters. Five minutes after winning the long jump, he was standing at the blocks; five minutes after that, the gun sounded. He started slow, as usual (Lewis is six two and weighs 175 pounds, which allows smaller men to outdistance him for the first 30 meters or so), then pulled away from everyone except Ron Brown of Arizona State, who hung at his shoulder and tried to beat him by leaning into the tape. Lewis won the race with a time of 10.13, but just barely, and his closest competitor wasn’t even one of the top four or five favorites.

The remaining semifinal heats went strictly according to form: Mel Lattany of Georgia won his in 10.11, Jeff Phillips of Tennessee won his in an identical time, and Calvin Smith of Alabama and Herschel Walker, a Georgia football player, were not far behind. Going into the finals half an hour later, Lewis had only the third-best time so far, and Lattany and Phillips had both proved in past races that they were world-class competitors.

Carl almost lost his composure just before the race began. The nine finalists were forced to stand in their lanes for what seemed like an interminable period of time so that Keith Jackson, the ABC announcer, could identify each one of them for the television viewers. He must have given complete life histories, for the camera moved down the line at a snail’s pace. It bothered Lewis, and several of the other runners as well, because the most important thing before a race is relaxation: if the muscles tense up, the game is lost. That’s why most of them go through a ritual of shaking their calves, jogging up and down their lanes, and doing “jump-ups” and simple calisthenics before the sprint. The value of these routines is not physiological but psychological: they keep the mind occupied. They make it possible to avoid thinking about the race, and thereby to avoid tension. Standing in one place for a TV camera is the opposite of relaxation.

Finally the cameraman moved onto the infield, and the starting judge, sensing the problem, sent the runners immediately into the blocks. Lewis was in lane six, with his two nemeses to his left—Phillips in lane five, Lattany in lane four. To his right was Brown, who had almost nipped him in the semifinals. He would be able to see, with his peripheral vision, everyone who had a chance to beat him. The only things standing between Carl Lewis and Jesse Owens’s 45-year-old NCAA record were 100 meters of Tartan track and his own capacity to relax and run intelligently.

It was the closest—and fastest—race of Lewis’s young life. And he began it by reacting much more slowly than usual to the gun. That has been his main problem in sprinting—partly a result of not working on the event as much as he works on long jumping—but this time he was clearly beaten out of the blocks by at least five of the runners. Herschel Walker seemed to have the lead for about 20 meters, but then his teammate Mel Lattany came on to take it away. Sprinters are able to accelerate for only 50 to 60 meters, or about six seconds, and after that their speed is continually decreasing. Hence the sprinter who slows down at the slowest rate is fastest. Lattany held the lead for almost exactly 55 meters, with Brown, Phillips, and Lewis all bunched up behind him. Then Phillips sailed past Lattany, and Lewis followed as though caught up in his slipstream. It was clear from that point that only Phillips and Lewis had the momentum to win, and even 5 meters from the finish they were in a dead heat. It was at that point that Lewis, just like the textbook says, began straining against his own velocity so that he could lean into the tape. He felt a short stab of pain—the first time that had ever happened in the 100—and suddenly knew he had won.

He didn’t even stop running. He continued around the far turn of the track, the tape streaming from his chest, arms lifted high over his head, and virtually danced past the grandstand. He ran over to hug his sister and his mother. Then, as the automatic scoreboard flashed the official times, he put his hands over his face and collapsed to his knees. He had broken the 10-second barrier for the first time in his life, with a wind-aided time of 9.99. (Jim Hines’s world record is 9.95.) Phillips was second at 10.00. And Lattany was third at 10.06. It was one of the fastest 100-meter races ever run.

Lewis had only two goals left in 1981, and two weeks after the Baton Rouge meet he achieved one of them. At the USA Track and Field Championships in Sacramento, he won the same two events, duplicating Jesse Owens’s 1936 feat, but even more important, he jumped farther than he had ever jumped in his life. He did it on his first jump in the finals, when he deliberately moved his takeoff back a few inches so as to be certain not to foul. Result: 28 feet 3½ inches, second only to Beamon, and good enough to beat defending champion Larry Myricks for the first time in nine meetings between the two men. After the 100 meters, Stanley Floyd, the defending champion in that event, said, “I consider Carl Lewis the number one sprinter in the world.”

And then, as though to prove that as well, Lewis left for Europe to make his way to the final challenge: the World Cup in Rome in September. At that meet he will face not only Myricks but the 1980 Olympic gold medalist in the long jump, Lutz Dombrowski of East Germany. In the 100 meters, he will face the best international sprinters in the world.

And then, of course, he must hurry back to Houston for fall classes, because he is only a sophomore and he has three more years of competitive jumping and sprinting to perfect his style for the 1984 Olympics. His coaches say that if he really wanted to do it he could probably compete in the Olympics in the 100 meters, the long jump, the 200-meter dash, and the 400-meter relay—just as Owens did at the Nazi Olympics in 1936. But by then he may simply be competing against himself anyway, at least in the long jump. Tellez will have lengthened his long-jump approach, or taught him the triple hitch-kick, or perhaps fully overcome the age-old problem of forward rotation, and Lewis will be both the world’s best jumper and the first true innovator the sport has ever had. Tom Ecker, the former coach of the Swedish national team and a respected track theorist, has already suggested what forms the innovation might take. He has proposed that the ultimate solution to forward rotation might be to go ahead and allow it to carry the athlete forward, completing a full somersault, with perhaps a half-twist, so the jumper could land on his feet and fall backward. It sounds outrageous, but so did the Fosbury flop. And on paper, the physicists say, it would propel the athlete much farther than when he is fighting the rotation.

Perhaps Lewis will walk into Tellez’s office one day next year and be confronted with the question: “Do you know how to turn a full somersault from a running start, do a half-twist in the air, and land on your feet?”

“No,” Lewis will reply.

“Well, you’re going to learn.”

Up in the Air

Just follow these simple steps and you too can jump 28 feet.

Lewis starts his run 147 1/2 feet from the pit. He takes 21 strides, some about 8 feet long, and is traveling at 27 mph by the time he reaches the board.

The last stride is shorter; he hits the board with his knee slightly bent so that when he straightens his leg, he propels his body upward and outward.

He’s almost at the apex of his jump and seems to be running through the air. To counter the tendency to go head over heels, he . . .

. . . rotates his arms and legs. This is the famous hitch-kick, and it brings him upright with his legs moving forward.

Lewis achieves enough height and distance to complete two hitch-kicks before landing. If he can work up to three, he might add more inches to his jump.

As soon as his heels touch the sand, he digs in and jerks both arms, which are behind him, out in front, keeping him from landing on the seat of his pants.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston