This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

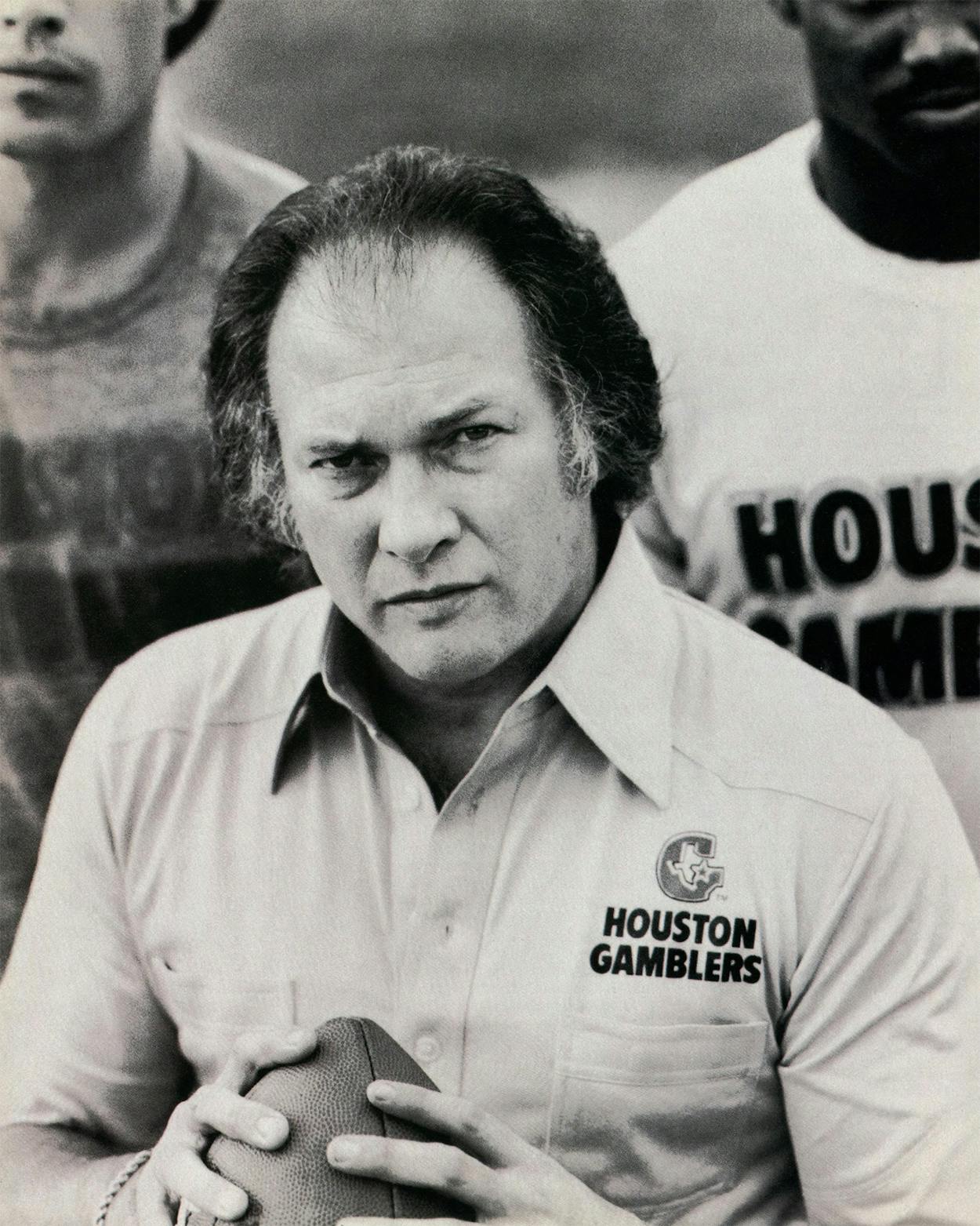

Jerry Argovitz, Houston doer of deals, had come to his office in one of his favorite outfits: a blue warm-up suit, nattily striped, with the jacket unzipped over a swatch of graying chest hair; Nike running shoes; no socks. His midriff and hairline heeded the demands of 45 years, but he still had the thick shoulders, misplaced bridge of nose, and impelling body language of the light heavyweight fighter that he once was. On the fourth floor of a new glass edifice near the Southwest Freeway, his office had a long and pleasant view over the treetops of Bellaire. By no coincidence, one suspects, that horizon culminated with the gray roof of the Astrodome, where this spring his football team will open its first season in the United States Football League.

CBS sports commentator Brent Musburger once burbled on the air, “Jerry Argovitz is the biggest name in football today, and he’s not even a player. He’s an agent!” While negotiating the contracts of many top professional players, Argovitz had driven hard bargains that shoved at the ceiling and left permanent cracks in the conservative salary structure of the National Football League. But his style of negotiating set him apart from other agents. Argovitz relied on invective as a primary bargaining tool. By his lights, there were no intelligent and fair-minded businessmen in the front offices of the NFL; those executives were pampered monopolists, descendants of the nineteenth-century robber barons. Six-figure salaries notwithstanding, their employees were glorified indentured servants.

Though Argovitz is no longer an agent, he still holds himself up as a champion of the players’ human rights and financial opportunity. A sworn enemy of the established pro league, he has set aside more-profitable interests to work full time as a managing partner of the Houston Gamblers, one of the new franchises in the springtime USFL. The manner in which he arrived on this unlikely side of the desk is a testament to his powers of ingenuity—or connivance, as his enemies have it. Ironically, he now finds himself voicing many of the same management policies and principles that he once assailed. Where you stand, he has found, sometimes depends on where you sit.

On the wall overlooking his desk was a framed cover of Sports Illustrated that bore a photo and the autograph of Detroit Lion Billy Sims, along with a warm inscription, “Dr. J. Together we make things happen.” In 1980 Sims was a rookie running back and “Dr. J”—Jerry Argovitz—was his rookie agent. Sims, a native of Hooks, Texas, and a Heisman trophy winner at Oklahoma, was one of those rare “franchise” players; like Tony Dorsett and Earl Campbell before him, he was considered an immediate superstar. As an agent, Argovitz had a knack for infuriating NFL management types, but Billy Sims had done very well by him, eventually signing a four-year, $1.7 million contract. Since then, Sims had soured on playing for a losing pro team in that grim Northern city, a situation that could rebound nicely for rookie owner Jerry Argovitz. There is nothing like a franchise running back to give a new team a little instant credibility. And as to whether it is unseemly for a former agent to use his relationship with his former clients to get them to jump leagues, well, football is a rough game, off the field as well as on it.

In fact, on this particular Tuesday afternoon, the Lions’ one star player was nowhere in sight, at least not in Michigan. He had recently suffered a broken finger that put him out of uniform for a few games, so he had received permission to go home for the weekend instead of making the team’s road trip to L.A. One of the other Lions had planted the devilish rumor that Sims was angry, that Sims thought the team doctors had misdiagnosed his injury, that Sims wasn’t coming back at all. Now, in Jerry Argovitz’s Houston office, the secretary announced a call that made Argovitz sit bolt upright in his chair. The caller was Monte Clark, the beleaguered head coach of the Detroit Lions.

“By Argovitz’s lights, there were no intelligent and fair-minded businessmen in the front offices of the NFL; those executives were pampered monopolists, descendants of the nineteenth-century robber barons.”

“Hey, Coach! How’s it going?” Argovitz erupted. “What? No. No, I haven’t seen him.” He listened for a long moment, then said, “Coach, I swear, I don’t know anything about it. I heard about the finger. But he’s not my client anymore. I couldn’t hold him out if I wanted to.” Those denials were fervent—Jerry likes Monte Clark—but at the same time distinctly gleeful. “Listen, if I hear from him, I’ll sure tell him to get in touch.”

Evidently reassured, the Detroit coach took the time for a few parting pleasantries. Argovitz grinned and propped the tread of his Nike on the furniture. “Hey, it’s a whole other world over on this side of the desk. You’d be amazed how much I’ve changed my tune.”

Argovitz has an adenoidal speech pattern that causes him to clip syllables, neglecting certain consonants and vowels. “Football” is “fooball,” “business” is “biness.” “I told my partner that we were gonna have to make a decision on bein’ in the fooball owner biness or stay in the agent biness. We couldn’t do both.” Critics of this former dentist maintain that Argovitz has in fact continued to function in both those capacities—business ethics and conflicts of interest be damned.

Still, the man knows his football, and there is a freshness and exuberance in his operation that is quite refreshing, particularly in contrast with the paranoid shambles of the NFL’s crosstown Oilers and the smug slickness of the Dallas Cowboys. On the day I visited, the office building had the smell of fresh paint; doors of suites down the hall awaited the installation of knobs. Even the club’s semiliterate press releases had an endearing quality. One quoted Bernard Lerner, the Gamblers’ other full-time working partner, on the USFL: “If the fans recognize a parody with the NFL in three or four years, then the league has accomplished what it set out to do.” The Gambler executives are like kids with a new and extravagant toy.

If they need reassurance, they can gaze across the Bellaire foliage at the hallowed Astrodome. Rice Stadium would have been far cheaper, but the Astrodome offered prestige and protection from Houston’s miserable spring weather. The lease was secured by another partner, Alvin Lubetkin, an executive of the Oshman’s sporting goods chain. The Gamblers are already beginning to make an imprint on the city’s consciousness. Their most serious head-to-head competition for the spring sports fan’s attention is the major league baseball team, the Astros. The football team’s billboards echo the baseball slogan by admonishing freeway motorists to “Catch Gambler Fever.” Another advertising pitch is cognizant of the endless agony of the Oilers’ 1983 season. Houston-area viewers of the Cowboys’ games catch the TV spot in which a forlorn fan sits alone in the bleachers: “Are you tired of spending your hard-earned money to watch your professional sports team lose year after year after year?” intones the Gambler voice-over. “Houston Gamblers, because you’ve waited long enough.”

The Gambler management has taken impressive strides since the franchise was announced in June. Gene Burrough, a former partner in Argovitz’s agency, is now football’s first black general manager. The head coach, Jack Pardee, was twice honored as coach of the year during his five years in the NFL, at Chicago and Washington. His staff includes: offensive coordinator “Mouse” Davis, whose collegiate prodigy at Portland State was current St. Louis star quarterback Neil Lomax; Bob Young, the former pro guard who anchored the Cardinals’ great line of the seventies and finished his career under Bum Phillips; and Pat Thomas, the recently retired all-pro cornerback with the Rams.

Of course, they have to have the players. Argovitz’s franchise rookie is University of Miami quarterback Jim Kelly. He was Buffalo’s first-round pick and the twelfth player selected in the NFL draft, which means he was rated right between Denver’s ballyhooed John Elway and Miami’s Dan Marino. Argovitz got Kelly by reminding him of the severity of Lake Erie winters and the durability of Buffalo’s excellent quarterback, Joe Ferguson; he signed the rookie to a five-year contract worth more than $2 million. The Gamblers also have the draft rights to two of Argovitz’s top former clients: Billy Sims and the Baltimore Colts’ Curtis Dickey. Having played out their NFL contract options, both players are available. Sims reportedly rejected a $3.5 million offer to renew his contract with the Lions.

“The name ‘Gamblers’ reflects the kind of people in Houston, Argovitz says. ‘People are coming from all over the country. They’re willing to take a risk on the future. That’s how the West was won.’ ”

“It’s not just a matter of money,” says Argovitz. “It’s a question of where you want to live. The best thing that happens in Detroit is that it gets dark at night. Think what opportunities Billy Sims could have had outside the game if he could have played in New York or L.A. or Dallas. When I was his agent, we went after the Lions tooth and nail, and a lot of it had to do with their attitude. Their GM told me it didn’t make a damn what I thought or said. If Billy Sims was going to play professional football in this country, it was going to be for the Detroit Lions. If he didn’t like it, he could find a job sweeping floors. The NFL had a total monopoly. But now the USFL gives the players another place to go.” On the bidding war for Sims and Dickey, he declares: “I can’t sign both of them. You’d have to play the game with two footballs to keep them busy. But my history with running backs is no secret. These guys are still my friends. If I don’t deliver one of that caliber, people are going to run me out of town.”

In the meantime, the Gambler executives have concerned themselves with enjoyable details, like choosing the colors for uniforms—red, black, and silver—and selecting a team logo—a red G on a field of black that incorporates the shape of the Texas map and the strategic placement of Houston. “My choice was four aces,” says Argovitz, “but you know, we kind of need to avoid too much of that.” Ah, yes, that name. USFL management’s choice of mascots has demonstrated a predilection for macho sleaze: Birmingham Stallions, Jacksonville Bulls, Oklahoma Outlaws. But the Houston nickname touched an especially sensitive nerve. Chet Simmons, the league’s commissioner, received a disapproving letter from ABC executive Roone Arledge, who alluded to a current NFL betting scandal that resulted in the suspension of Baltimore quarterback Art Schlichter.

Argovitz insists that the name was foremost a gesture to his friend and limited partner Kenny Rogers, the country singer whose biggest hit was a song of that title. “It didn’t have anything to do with Vegas or shooting craps or betting on games,” Argovitz says. “Hell, let’s don’t be too hypocritical. They give the betting line on NBC. If you take the gambling out of football, we’d probably be watching ice skating on Sunday. The name reflects the kind of football we intend to play. I told Jack Pardee, ‘You’re never going to get fired for going for it on fourth down.’

“This new league’s a gamble, an exciting gamble,” he continues, waxing eloquent. “Houston’s exciting too. The name ‘Gamblers’ really reflects the kind of people in this city. People are coming from all over the country. They’re willing to take a risk on the future. That’s how the West was won. People getting on horseback and fighting the Indians and buffalo and gambling with their lives and fortune. The oil people of this great state. The builders and developers gambling that they can go out there and build a sixty-story building and lease it up. Houston was based on gamblers, risk takers, from the cab drivers to the big lawyers to the guy who sells shoes in a store.”

He comes to a halt, winded but unabashed. “Listen, our motives are pure.”

Argovitz grew up in Borger, a sleepy Panhandle town whose dust was sootier than most because of its carbon black plant. He was a freshman walk-on quarterback at Texas in 1956, but his grades were a casualty. A transient but persistent student, he landed at a number of junior and small-town colleges on boxing scholarships before gaining admission to the UT dental school and finishing at the University of Missouri in 1964. His first wife came from Houston, which prompted him to open his practice there. Even then he demonstrated more interest in numbers than bicuspids. He offered his services as a tax and investments planner to fellow dentists and eventually represented more than two hundred clients. After only nine years of dentistry, he retired with a forthright ambition—to get rich in banking and real estate. He became a full-time Houston wheeler-dealer and arrived at one summit of his ambition with a Ferrari, a Mercedes, and a twenty-third-story condominium overlooking the Galleria. Shortly after his divorce in 1982, he married J. J. Vickers, a successful model from Los Angeles.

The late seventies were the Camelot of Houston football—Bum Phillips’ Oilers were the toast of the town. Jerry Argovitz was one of those fast-lane businessmen who have the style and connections to pal around with the jocks. He ran with golden boy quarterback Dan Pastorini and nose guard Curly Culp. Phillips’ grandstand trade with Tampa Bay for the draft rights to Earl Campbell had brought a good Oiler team to the brink of greatness; Campbell’s contract had been negotiated by Californian Mike Trope, then the top agent in the business. At a party one night in 1979, the subject of Campbell’s contract came up. Argovitz remarked, “If he got what I heard he got”—a $650,000 signing bonus deferred in payment over thirty years with no interest, which is no way to beat inflation—“then my grandmother could have done a better job for him. And she’s been dead for ten years.”

A broad-shouldered young black man heard that flip remark and steamed. Gene Burrough had come to the party with his younger brother, Kenny, the Oilers’ whippetlike wide receiver. As a recruiter of rookie clients, the older Burrough had delivered Earl Campbell to Trope. He thus introduced himself to Jerry Argovitz by pointedly implying that the cocky, frizzy-haired businessman did not know what the hell he was talking about. Burrough recalls Jerry’s reaction with amusement. “He was a little taken off guard, but the man comes right at you. He said, ‘Listen, you guys did a shitty job!’ We wound up talking through most of the party, and he told me, ‘If you ever decide to get serious about this business, come see me sometime.’ ”

As it happened, Earl Campbell was desperately trying to renegotiate his original Oiler contract, and Mike Trope’s star as an agent was in rapid eclipse. Argovitz began his agency as a one-year experiment, with Gene Burrough as a partner; it took off like a comet. They decided to go after only the anticipated top players in the NFL draft. Of ten names on that original 1980 list, Burrough delivered seven. One was Billy Sims, the first player chosen in the draft and eventually the league’s rookie of the year. Auburn runner Joe Cribbs signed with Buffalo and was the American Conference rookie of the year. The professional career of Texas A&M runner Curtis Dickey has been hindered only by his misfortune of playing for Baltimore. Another initial client, George Cumby, has since played linebacker more than respectably for Green Bay.

The agency’s success, especially with Sims, became a topic of spirited debate in the industry. Argovitz says that the decisive factor was his financial statement. “These are twenty-one- and twenty-two-year-old kids who are getting ready to come into some pretty serious money. Some of them have never even had a car. They get too much too quick, and they’re not prepared to deal with it. If they’re making a hundred thousand dollars a year, they’re going to spend a hundred and twenty. But the image of football players as big dumbos is a notion that needs to be laid to rest. The complexity of the game today is such that if they don’t have some brains, they won’t have to worry about the NFL draft. And some of these guys already have the acumen and business contacts. They’re thinking about tax shelters and real estate, the needs of their mothers and brothers and sisters. I never represented a black athlete who didn’t want to take care of the family first. Blew me away. And they want to be in a position that when it’s over, nobody’s going to take the house and car and lifestyle away. Billy Sims handed me my reputation at a news conference in Houston when we signed him. He said, ‘I didn’t hire Jerry Argovitz because he’s an agent. I hired him because he’s a good businessman, and he’ll teach me how to be a businessman.’ ”

Using the media to gain leverage, Argovitz was profane, outrageous, and good copy—particularly when his opponents rose to the bait. When the owner of the Detroit Lions characterized Billy Sims’ agent as “a Machiavellian idiot,” Argovitz retorted, “I don’t know what that means, but the same to you, buddy.” During his representation of Curtis Dickey, Argovitz told reporters that Baltimore’s general manager had “the IQ of a plant.” That was his first sin, in the eyes of management. He insulted them in public. He fought his battles in the press.

The focus of Argovitz’s wrath was the NFL’s method of achieving parity among its teams. The worst teams get first pick from the new crop of rookies each year, and to enforce that distribution of talent, the NFL relies on total restriction of player movement. The pros play where they’re told to play. “They don’t call it a draft for nothing,” Argovitz says. “It really is like the military draft—they own you till they’re through with you.”

In 1981, his second year as an agent, he delivered running back David Overstreet and linebacker Keith Gary, the first-round choices of Miami and Pittsburgh, to the Canadian Football League. “If I’d gone into Pittsburgh with my cowboy boots on, those fans would have strung me up from a light pole. But they were mad at the wrong people. I got those kids the same money for two years in Montreal that Miami and Pittsburgh were going to pay them in five, and the contracts were guaranteed. If they turned into penguins or midgets, they got paid.”

Argovitz really set the bridges afire a year later in the negotiation of Joe Cribbs’ second contract with Buffalo. The runner’s performance had exceeded all expectations, yet the Bills’ management had alienated him from the start. By the time the new negotiations began, Argovitz had a very bitter client. When one contract offer came close but fell through, he committed the agent’s unforgivable sin. He held Cribbs out of camp. Sending the top rookies of two league dynasties to Canada was one thing. But after years of losing, Buffalo was now an aspiring Super Bowl contender without its star player.

“Do you realize that general managers in Baltimore, Miami, and Buffalo lost their jobs because of me?” Argovitz would crow. But in the sports-agency business, the comets have a characteristically short arc. Though Argovitz retained the loyalty of most of his old clients, he received few recommendations from the players’ union, and upcoming rival agents were giving it to him in the same way that he had pilloried Mike Trope. One of the raps on Argovitz as an agent was that he cared nothing and did little for those clients who might be drafted below the second round. And even with the certain first-round picks, these accusations went, he charged 7 per cent of the total contract figure (as opposed to many agents’ 4 per cent) on the grounds that he offered extra business management and consultation, then forgot about them till the next contract negotiation came up.

Argovitz and his partner were convinced that the more serious heat came from NFL management. “This past year it really became apparent that the NFL was trying to discredit us,” Burrough says. “These kids wouldn’t sit down with us for five minutes. ‘You with Jerry Argovitz? Hey, man, I’m sorry, I don’t want to have nothing to do with you. You guys are bad news.’ I took it personally. I was hostile as hell to the NFL. They were systematically putting us out of business.” Some NFL scouts told college players that if they hired Argovitz, they might not be drafted at all. Though the agency hired two full-time recruiters, by January 1983 Argovitz had a grand total of two rookie clients, one a tackle whose prospects were no better than the fifth round. To stay in the business, Argovitz would have to follow the lead of the new ascending comet, California attorney Howard Slusher, who specialized in big-money holdouts by veterans and conceded the rookies to the young lawyers invading the field. Or Argovitz could approach the football business from an entirely different angle.

The history of challenges to the National Football League is not an inspiring one. The American Football League in the sixties was the exception; the short-lived debacle of the World Football League in the seventies is the rule. On the other hand, pro football enthusiasts have long contended that fan interest projects far past the end of the NFL season. Backed by adherents like NFL patriarchs Paul Brown and George Allen, the idea of a spring football season has been kicked around for many years.

In 1982 several ownership groups, some with vast resources, set out to implement that idea with the United States Football League. A New Orleans art dealer, Dave Dixon, had the contacts and the wherewithal to organize the league. In return, USFL owners rewarded Dixon with a team franchise, free of charge, that could be activated within the first five years of the league. In Houston Jerry Argovitz, like most wheeler-dealers, knew when to move on. While Gene Burrough and the recruiters were out beating the collegiate bushes, Argovitz was cultivating a relationship with Dave Dixon. Though Dixon had no wish to run a team, he stood to make a tidy profit by selling his franchise. And when the time came, Argovitz stood first in line to buy.

In July 1982 Argovitz talked a most reluctant Dixon into allowing him to come to an owners’ meeting as the organizer’s consultant. He knew his antimanagement reputation preceded him. In fact, if his chances of acquiring a team had depended on the usual process of awarding an expansion franchise—which requires the approval of the owners—he wouldn’t have bothered to fill out an application. But he argued that the NFL was a more appropriate enemy than Jerry Argovitz. He impressed the owners with his knowledge of the business. In turn, he was impressed by the caliber of men attracted to the new enterprise. “They got guys that could buy me out of their back pockets. There’s rich, and there’s rich. I mean, real rich.”

Without the owners’ knowledge or assent, Argovitz and Gene Burrough met with Herschel Walker, the Georgia running back, before last January’s Sugar Bowl game with Penn State. Walker had nothing more to prove at Georgia; he had already won the Heisman and played on a national championship team. But he was only a junior, which meant he was ineligible for the draft. The NFL policy against recruiting juniors has nothing to do with a desire for its players to complete their college educations. Basketball and baseball players routinely jump to the pros after their junior seasons. But football is the collegiate money sport. It underwrites the entire athletic program of some schools and has its own huge power base. Observing the NCAA’s four-year eligibility rule is the pro league’s way of keeping peace with its tacit farm system. Fearing the wrath of college administrators and coaches, USFL owners had voted eleven to one to practice the same restraint.

Herschel Walker had flirted with bucking the system in court as a sophomore. Now Argovitz told him that he didn’t need an agent—he needed a lawyer who could force the USFL’s hand. If he really wanted to turn pro, he could make the new league meet his price by threatening a lawsuit. And by doing it now, after the USFL’s first draft, he could choose the place he wanted to play. As any thinking superstar would have, he chose the New York City area’s New Jersey Generals and settled for a price of $3.2 million. Although Walker’s career got off to a slow start for a mediocre team, he gave the USFL instant credibility.

In Argovitz’s view, the USFL has supplied pro football players with the free agency that NFL management so tyrannically denies them. All the big-name veteran and rookie defections have certainly gotten the NFL’s attention. The USFL’s January draft precedes the NFL’s by three months, a source of great anxiety. In hopes of postponing the decisions of some of the prospects, NFL scouts have been telling likely eighth- or ninth-round picks that they’re certain to go in the second or third. And with last spring’s first-round picks, the NFL reaction was downright panicky: executives offered million-dollar-plus deals all the way down the line. It was unprecedented.

During 1983, while getting out of the agency business, Argovitz maneuvered behind the scenes as a personnel broker for the USFL. He brought his disaffected Buffalo client, Joe Cribbs, home to Alabama with a 1984 contract to play for the USFL’s Birmingham Stallions. He claims credit for the decision of a big-name NFL quarterback, Tampa Bay’s Doug Williams, to jump leagues. “I called those guys with the Oklahoma Outlaws and said, ‘Do you want Doug Williams?’ They said, ‘Are you kidding?’ ” Overnight, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, an NFL play-off team, joined a race with the Houston Oilers to become the laughingstock of the established pro league.

If Argovitz signs Billy Sims, who has appeared at several Gambler functions while still playing for the Detroit Lions, the former agent intends to work just as hard at placing Curtis Dickey with another USFL team, perhaps San Antonio. “We put the NFL on notice,” says general manager Burrough. “Any player that we ever represented can find a place to play in the USFL.”

The Dallas Cowboys’ Gil Brandt sighs, “I just hope they have a lot of money to lose. Over here, I suspect that every veteran player whose contract is up will claim to have a big offer from the USFL. We’ll have to let them cry wolf, which means we’ll lose one, we’ll lose two. But our salary structure will stay about the same.” In last April’s NFL draft, the Cowboys took the lead in expending late-round choices on rookies who had already signed with the USFL. The tactic anticipates the outside chance that the new league will belly up as quickly as the World Football League did, and in the more likely event, it precludes a free-agent auction for those young players in two or three years, when their USFL contracts expire and they want to move up to the big time. Gil Brandt questions how long the USFL’s centers, tackles, and defensive backs will be willing to play for minor-league wages while the “impact players” like Joe Cribbs and Doug Williams take home millions.

In retaliation for all this brigandage, one NFL team hauled the USFL and the double-dealing Argovitz into federal court. The 1983 season was supposed to be the year of the San Diego Chargers. Not only were the Chargers coming off several play-off years in succession but through astute trading they also had one of the best positions in the NFL’s April draft. Unfortunately, one of their first-round picks, Arkansas runner and receiver Gary Anderson, was the last major client of agent Argovitz, who continued to represent Anderson even though he had formed the Gamblers partnership in March. The USFL’s New Jersey team had also drafted Anderson, but the Generals lost interest once they set their sights on Herschel Walker. With the Chargers, Argovitz fell back on his customary practice of negotiating slowly. Anderson participated in the San Diego mini-camp in late April. In contention for the USFL play-offs, the Tampa Bay Bandits meanwhile lost their top running back to an injury. Owner John Bassett notified Argovitz that the Bandits were interested in Anderson if he could be signed at once. While the NFL’s Chargers were offering a three-year, $830,000 contract, the USFL’s Bandits went $1,375 million for four. After San Diego declined Argovitz’s final offer—$975,000 for three years—Anderson accepted Tampa Bay’s proposal and agreed to sign the contract in four days. Argovitz told Anderson to go home and have his phone calls screened. That same day, May 5, while the Charger executives frantically tried to reach Anderson, USFL owners officially certified Argovitz’s purchase of Dave Dixon’s franchise. The next day, tax planners from Argovitz’s management company urged the rookie to pay the agency’s entire fee of $96,250 up front, citing tax advantages. The San Diego general manager claims he phoned a last-ditch, $1.5 million, four-year offer to Argovitz before the Tampa Bay contract was signed May 9. Those numbers never got to Anderson. Argovitz denies he ever received the call.

San Diego owner Gene Klein hit the roof. Apparently unaware of Argovitz’s private deal with Dave Dixon, Klein did know that Tampa Bay owner John Bassett headed the USFL’s expansion committee. Klein dispatched Lloyd Wells, a Houston sportswriter and former member of Muhammad Ali’s entourage, to court the player. Though Anderson was playing quite spectacularly for Tampa Bay at the time, Wells bought him a Nikon camera and a leather jacket and persuaded him to fire Argovitz as his agent. Under Wells’ tutelage, Anderson hired Houston lawyer Charles King to sue Argovitz, Bassett, and the Bandits in federal court. Anderson then signed San Diego’s four-year, $1.5 million contract. King outlined a scenario of manipulation and collusion in which the award of the Houston franchise was dependent upon Argovitz’s delivery of Anderson to Tampa Bay. Argovitz was further accused of failing to inform his client of his USFL franchise and of misrepresenting the San Diego offer.

In upholding the Tampa Bay contract and denying the injunction that would have enabled Anderson to play for the Chargers, Judge Norman Black implied that San Diego was the party most guilty of manipulation, through its backing of the suit. He found no evidence of collusion between Argovitz, Bassett, and the USFL. In fact, Argovitz’s reputation as an agent bore up well under the attack. The judge found that because less money was deferred and three years of the salary were guaranteed, the USFL Tampa Bay contract that Argovitz had negotiated for Anderson actually “has as good or better present value than the one he got from San Diego”—even though the Chargers knew precisely what they had to beat.

As for the ethics of playing both sides of the fence, Argovitz is totally unrepentant. He even gloats over another deal from that same period. While representing Anderson, he had also received permission from the USFL’s Oakland franchise to go after Arkansas linebacker Billy Ray Smith—the Chargers’ other first-round pick. Argovitz says he dropped out of the bidding at about $900,000, but San Diego didn’t know that. Smith’s agent used the USFL threat to more than double the cost of that contract to Gene Klein. “Poor guy,” commiserates Argovitz, poking his cheek with his tongue.

Argovitz and Burrough have had a delightful year tormenting the NFL, but now they have to deliver in their own league. They have the Astrodome, a big-name coaching staff, a heralded and untested rookie quarterback, the likelihood of a star veteran runner, and a long list of unknown quantities who flunked their tests in the NFL. The Gamblers’ projected defensive star, Kiki DeAyala, was a superb pass rusher at the University of Texas, but the NFL rated him no higher than a sixth-round choice. The team can look forward to scores of free-agent prospects and another rookie draft to beef up the roster, but the Gamblers had better hurry if they wish to dispel Argovitz’s fear of playing minor-league ball. Of course, they couldn’t have picked a better year to be the new team in town. In 1983 the Oilers gave up and started over; the only remnant of the Bum Phillips years is the problem of how to ease the pain and embarrassment of Earl Campbell. In fact, nostalgic Oiler fans may look to the Gamblers for some of those familiar faces. Argovitz has signed rotund kicker Toni Fritsch and hopes to sign Ronnie Coleman, on occasion a splendid runner who unfortunately played the same position as Campbell and Rob Carpenter. And if Gene Burrough’s brother Kenny, whom the Oilers unceremoniously waived out of camp last summer, hasn’t caught on with an NFL team by the end of the current play-offs, he will likely sign with the Gamblers.

Very quickly, Argovitz and Burrough have seen old principles dissolve in the face of pragmatic necessity. “I’m trying to avoid getting too close to the players now,” says Argovitz, “because I’m going to have to cut so many. But when we’re down to the final forty, we’re all going to be family—foxholed together. Players are going to want to come here because of it. It’s going to be an employer-employee relationship, but I can promise them one thing: we’ll be fair.”

Inside the NFL Players Association, which views the USFL with awkward ambivalence, one official greets that pronouncement with utter cynicism. “The USFL had an expansion draft in which the original teams made some of their players available to the new franchises,” says the union official. “There was an offensive lineman picked up by Houston. This guy’s a good player; he’ll probably start for them. But he had a pathetic contract with his original team. Twenty-two thousand the first year, twenty-four the second. The guy was doing cartwheels when he found out he was going to Houston. My God, Jerry Argovitz! But when they got together on the phone, suddenly Argovitz was saying: ‘Listen, I’m under no obligation to renegotiate that contract. I expect you to report for camp. If you don’t, you can be fined and you can be suspended.’ ”

The most stunning managerial turnabout has revolved on the issue of free agency. If the USFL survives and prospers, will Gambler management lobby for a fair policy that will enable the players to move around within the league? Not a chance. “I understand the need for a draft now,” explains Burrough. “It’s important for parity—and to keep the salaries down. I understand the need for a lack of freedom. To keep the wages at a reasonable level, obviously we can’t allow the guys to move around inside our league. You got to have some controls. Still, I don’t think they ought to have no freedom at all. The mere fact of having two leagues now, that’s freedom enough.”

Argovitz is more diplomatic in his disavowal. He claims that he was never interested in free agency as an internal labor dispute. When he was an agent, it just represented the best chance of guaranteeing his clients an option. If he has his way now as a team owner, the only option the players will ever have is to jump between leagues. “If they don’t like their situations in the NFL, they can come over here,” he says. “And when their USFL contracts are up, they’ll be free to shop around in the NFL. I wasn’t seeing it the same way back then. Football players aren’t like baseball and basketball players, who may play ten years and more. The average pro football career lasts just over four years. If we let the players move around, we’ll never have a chance to develop those team and regional loyalties. You’ve got to think about the fans.”

Wearing his Nikes and striped warm-ups, Argovitz weaved through a freeway tangle of Sunday drivers in his brown sun-roofed Mercedes, talking on the mobile phone to his GM. “Yeah, they found a way to do it again,” he said, referring to the Oilers’ latest loss. As usual, Jerry’s mind was on football, but he needed to check on a real estate project south of Rosenberg. After Gene hung up, Jerry said, “By God, you build a football franchise and league the same way you do the deal on a subdivision: from the ground up. You start with the basics and do it right. You make sure the zoning is in order. You lay the sewer lines, connect the utilities.”

I was thinking that the real spook in Jerry’s dream was a fundamental resistance among his potential followers, the fans. I, for one, went out of my way last year to avoid watching a single series of USFL downs. The greatest disadvantage of the spring schedule is not the competition of rival team sports, it’s the seasonal desire to enjoy the break in the weather, to get outside with the kids, to plant tomatoes in the garden. A friend put it this way: “Listen, I am a football fan, but I’m not going to fall in that trap. Part of it is loyalty to baseball. Another is not knowing who these new guys are. And the truth is, I don’t want to know. I’m already glued to that tube every weekend from September through January. Damn it, I’m not going to let them hook me through the month of June. I can’t do that to my family.”

Jerry has answers to those objections, of course. The USFL can reconcile some of the conflicts by scheduling more games at night. In any event, he hopes the spring schedule will be a temporary aberration. There has been much speculation that when the NFL’s current network contract expires, after the 1984 season, the league will try to multiply its television bonanza by offering its own cable system. Facing a huge loss of advertising revenue, where could the networks go but the USFL? Suddenly, the two leagues would be playing the same time of year.

Jerry pulled into the new subdivision called Horseshoe Bend. The street signs bore names like “Kiowa,” “Apache,” “Geronimo,” “Custer,” with only one thematic departure, “Epstein Way”—Jerry’s favor to an Israeli employee who wanted to send a photograph home to his family. The streets of this subdivision “done right” were unpaved and roughly graded. No trees, no shrubs, no St. Augustine lawns. In the twilight mist, the scene carried a shock, like seeing an old and ugly person nude. Dogs crawled from under mobile homes to howl their territorial claims. “I like underdogs,” Jerry said proudly. “Where else can these people have an acre all their own for a hundred sixty dollars a month?” Some children ceased throwing a white football to stare at the rich man’s foreign car.

On my part, there was a very long silence. “Another thing I hope to see is the Galaxy Bowl,” he finally blurted. The what? “The Galaxy Bowl,” he explained, as the Mercedes gained speed. “The winner of the Super Bowl plays the winner of our league. It’s got to happen. Except instead of just playing one game, I say we do it the best two out of three.” The premise of this engaging man’s dream is that there can never be too much of a good thing. Football season doesn’t have to be a sheaf of pages on the calendar. Like the city limits of Houston, it’s mostly a state of mind. It goes on and on and on.

The Argovitz Touch

Once Jerry Argovitz was just an NFL agent. Today he is a USFL agent provocateur. Whether he’s raiding the NFL to coax his old clients to change leagues or invading the colleges to secure new stars for the USFL, it will probably be his fault if the skirmishing between the establishment league and the upstart league ever breaks into open warfare.

Jim Kelly

Miami, Buffalo Bills

Refused NFL offers to become Gamblers’ quarterback for $2 million plus.

Joe Cribbs

Auburn, Buffalo Bills

Spurned NFL to play with USFL’s Birmingham Stallions in 1984.

Gary Anderson

Arkansas, San Diego Chargers

Rejected NFL through Argovitz’s agency to play for Tampa Bay in USFL.

Billy Sims

Oklahoma, Detroit Lions

Signed with NFL for $1. 7 million, now may be headed for the Gamblers.

Curtis Dickey

Texas A&M, Baltimore Colts

Joined NFL in 1980, now wants to come in from the cold—to the USFL.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Football

- Houston