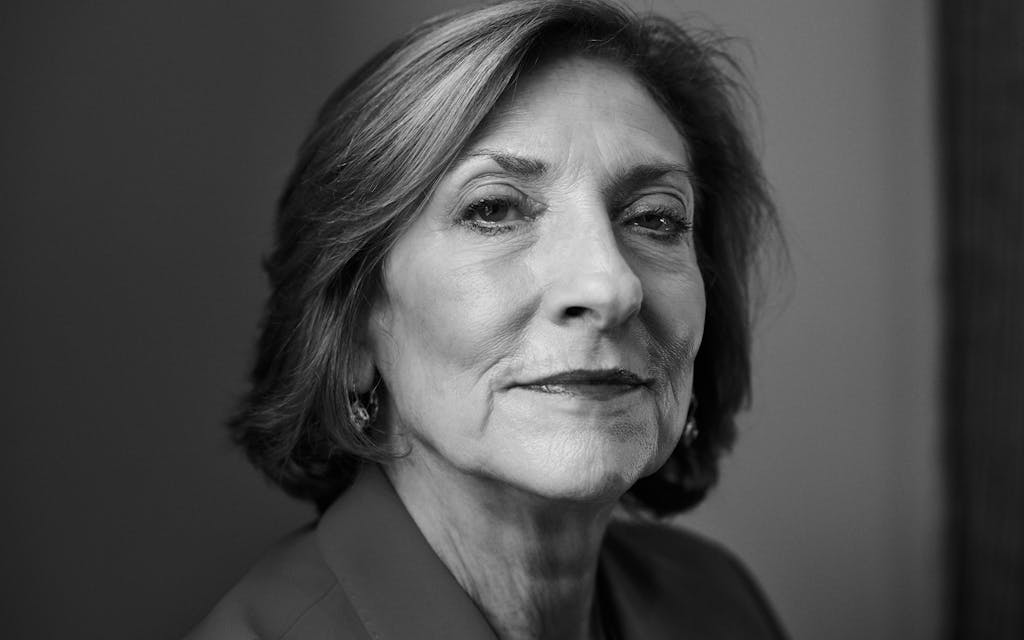

The walls of Lesli Linka Glatter’s home office tell a rare Hollywood story: success. Eight Emmy nominations, eight Directors Guild of America nominations, including two wins for her work on the Showtime series Homeland. Glatter lives in Pacific Palisades, California, just up the coast from Santa Monica, in a home that is posh but unshowy, filled with art and nooks perfect for curling up with a book.

“There was a point where I almost bought the big house,” she says, in the slightly sultry alto that points back to years of smoking, though she quit decades ago. “But then I realized if I did that, I would have to take every job ever offered me, and I decided that I didn’t want that career. I wanted to be able to say no to things I didn’t love.” At 69 the Dallas native moves with the casual elegance of a dancer—her first vocation—as she sets out our lunch of delivery sushi. “To me, freedom is everything,” she says. “Be sure you’re in control of the choices you make.”

The choices she made built a formidable career in an industry that has proved stubbornly resistant to women. “When you look at a film crew, you’d think you’re on a construction site,” Glatter says. All that grunt work and testosterone. For a long time, men were the captains of this ship. “Women excelled in the editing room and the writing room,” she says, but they weren’t calling the shots. That’s been changing.

The new golden age of television, as the past quarter century is often called, is a triumph for a once derided medium that has, arguably, overtaken cinema in cultural primacy. What’s less well known about this transformation is the role women have played as showrunners, directors, writers, and empire builders. This era of television, in other words, has led to something of a golden age for women in the industry. Glatter has both witnessed and nudged along this quiet revolution. Hers might not be a household name, but if you’ve been watching any of the iconic shows of the past few decades, chances are you’ve seen her work. A lot of it.

Glatter has directed nearly 150 episodes of shows such as Twin Peaks, The West Wing, Mad Men, and Homeland, for which she directed 25 episodes and served as an executive producer. Most recently, she sat behind the camera for the Max limited series Love & Death, based on the 1984 Texas Monthly stories about a North Texas housewife who killed her friend with an axe after having an affair with her husband. (Texas Monthly was an executive producer on the series.)

“Women are totally suited to directing,” she tells me. “You have to multitask, play well with others, motivate people.” The director’s job, she explains, “is to delve into emotional territory.” I asked Elizabeth Olsen, who stars in Love & Death, about working with Glatter. “She has more energy than anyone I’ve ever met, and it’s contagious. She’s so positive and kind,” she said. “She comes to set with a very specific plan, but she’s very comfortable abandoning it if someone has a better idea.”

Glatter’s instincts as a creator were honed through a career that’s taken her around the world, but filming Love & Death took her somewhere she hadn’t been in a long time: back home to Texas.

Glatter was born in Dallas’s leafy Walnut Hill neighborhood, the only child of two loud liberals in a conservative town. Her youth included the typical North Dallas set pieces: school at Greenhill, pizza at Campisi’s Egyptian Restaurant, on Mockingbird Lane. But her parents’ politics—she remembers walking through a sea of Kennedy-Johnson signs on her front lawn on her way to grade school—made her feel like a bit of an outsider. Her father, Robert, worked for the International Ladies Garment Union. Her mother, Toni Beck, was a trained dancer who opened a studio in Highland Park and helped found Southern Methodist University’s dance department.

Her parents divorced when she was twelve, and life split into two addresses, but her mother’s studio was home. Glatter had announced at an early age that she’d be a neurosurgeon, and she attended Washington University in St. Louis for a year as a premed student. But the pull of the barre, the elegance of the outstretched arm and upturned leg, proved too strong. She transferred to SMU to study dance, and after graduating, she began the itinerant life of a contemporary dancer, in London, Paris, and Tokyo, where she performed and taught modern dance through the U.S. Information Service.

It was a chance encounter in Japan when she was 25 that led her to filmmaking. Glatter was looking for a cup of coffee in Tokyo’s bustling Shibuya district when she saw two cafes near each other. She arbitrarily picked “the one on the right,” she remembers. The place was packed, and the only open seat was next to an older Japanese man, Yutaka Tsuji, who waved her over. He was a former Buddhist monk and war correspondent who was working as the head of cultural affairs for Asahi Shimbun, one of the largest newspapers in Japan at the time.

They became friends and stayed in touch even after she left Japan a few years later, somewhat reluctantly, to settle in Los Angeles with her second husband, whom she’d met in Tokyo.

Before Glatter left Japan, Tsuji told her stories about his life during wartime. He’d been an interpreter at a Japanese military prison camp in 1944, but a year later he became a prisoner of war in that same camp. Glatter was enthralled. “I knew I had to pass on the stories,” she says, “and I knew it wasn’t through dance.”

Film wasn’t an entirely random choice. While in Japan, she had started diving into cinema and watched classics by directors such as Akira Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi, and she’d met director George Miller while he was there for the release of Mad Max. When she later told Miller about Tsuji’s stories, he suggested that she make a film.

But how? Glatter was still a dancer and had a job performing, teaching, and choreographing at California Institute of the Arts. But living in L.A. proved fortuitous. On something of a lark, she applied to and—to her surprise—was accepted into the American Film Institute’s Directing Workshop for Women. She knew next to nothing about filmmaking. What’s a best boy? What’s a key grip? She volunteered to work on several of her classmates’ films. By the time she made hers, a thirty-minute narrative about Tsuji’s experience called Tales of Meeting and Parting, she knew her tools.

Glatter’s film was mostly in Japanese and had exactly one Caucasian character. “I did everything I was told not to do if you want a career in Hollywood,” she says. But she wasn’t looking for a career in Hollywood.

She got one anyway. Tales of Meeting and Parting was nominated for an Academy Award for best live action short in 1985. Glatter was 31 and had never been in a limo until she rode in one to the Oscars ceremony. She wore a vintage Norell dress, very Audrey Hepburn, that she’d found at a resale shop. The limo pulled up to a throng of paparazzi hoping for Sally Field (Places in the Heart) or Prince (Purple Rain) or F. Murray Abraham, who starred in Amadeus, which would be the big winner that night. When Glatter stepped onto the red carpet, what she heard was “It’s nobody!”

She didn’t win, but not long after, her phone rang, and a voice told her Steven Spielberg was on the line. She thought it was a joke, so she hung up. Fortunately, Spielberg called back.

He was dabbling in the small screen as an executive producer for a half-hour-long, Twilight Zone–esque anthology series on NBC called Amazing Stories. Clint Eastwood, Martin Scorsese, and other big names were brought in to direct episodes, but Spielberg wanted to include newcomers too. This was the deep end for a woman who’d barely dipped a toe into directing, so she asked Spielberg the first question that came to mind: “Can I shadow you?”

He agreed, letting her trail him on one of his episodes of Amazing Stories. She learned from his technical mastery but also from his faith in his own vision. Filmmaking is a collaborative enterprise and a director has to field endless opinions, whether it be from the studio head or grip number four, but Spielberg taught her to never lose the connection to her gut. “When you tell your instincts to shut up, they will, and they won’t talk to you anymore,” she remembers him saying. He became a mentor and friend.

A few years after Amazing Stories, another superstar mentor came along in David Lynch, whose work was a dark-hearted counterpoint to Spielberg’s crowd-pleasing epics. At the time Lynch was working on Twin Peaks. Glatter remembers gasping when she saw the pilot. “It was unlike any TV anyone had seen,” she says—funny, twisted, lush in character and style. “I think that’s why I never saw television as a lesser medium.” The show indeed had a cinematic flair that, in hindsight, feels like a forebear of today’s prestige television. Lynch brought in Glatter to direct four episodes. Television had changed her life, and the work she’d help create over the next decades would change television.

In 1996 Annie Leibovitz photographed fourteen female directors for Vanity Fair’s annual Hollywood issue. The image is making a statement: Look at these women! So many women!

Amy Heckerling, wearing a boxy jacket and a jaunty brimmed hat, had just directed Clueless, a teen comedy that would come to define the nineties as much as her Fast Times at Ridgemont High had the prior decade. Jodie Foster, petting her dog in center frame, directed Little Man Tate, in 1991, and had just finished Home for the Holidays. And there’s Glatter in the back, fresh off directing her first major feature, Now and Then, a slice of girlhood nostalgia starring Melanie Griffith, Demi Moore, Rosie O’Donnell, and Christina Ricci. The reviews were lackluster, but the box office wasn’t. Now and Then raked in $37.5 million on a $12 million budget.

In 1998 Glatter made The Proposition, a psychological drama starring Kenneth Branagh, but it flopped. She has never made another film. That’s how it went for women in Hollywood. If one project didn’t land, “you went to movie jail,” Glatter says, and studio heads were quick to throw away the keys.

But the door to directing television remained open, not just to Glatter but to women generally, perhaps because (unlike in cinema) the mighty showrunner—usually the show’s creator or executive producer, if they weren’t the same individual—sat atop television’s hierarchy, while directors were more like hired hands that were brought in to help with a grueling 22-episode season.

Glatter played the latter role for several shows. In the nineties and aughts, she worked on such hits as ER, NYPD Blue, and Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. At the same time, she was raising her son, Nick, who was born in 1991, with her partner Clayton Campbell, a photographer and painter. Nick grew up going to work with his mom. One time she took him to the set of ER, which starred George Clooney. “I was like, I get to hang out with Batman today?” he told me.

But the grand arrival of female directors trumpeted by that Leibovitz photo never really materialized. “There were always a handful of women working,” Glatter says. “It was just really hard to move the needle past that handful.” Glatter would be featured in more women-on-the-rise photo spreads over the following years. That was the story for a long time. Women in Hollywood were forever “on the rise.”

But change was coming to the industry, and Glatter would be a part of it. Sometime in the late nineties the script of a quirky pilot about a mother-daughter friendship crossed Glatter’s desk. The show, created by Amy Sherman-Palladino, was Gilmore Girls. Sherman-Palladino was a witty writer who’d sharpened her sword on Roseanne, but as a showrunner, she struggled to realize her vision on the set, in part because she didn’t have much experience behind the camera. “Lesli is the one who taught me about walk and talks,” Sherman-Palladino said in the 2018 book Stealing the Show: How Women Are Revolutionizing Television. “She is a dancer, and she moves that camera so beautifully.”

Glatter directed the pilot, and the show became a reliable prime-time pull for the WB channel. More female-driven shows followed. While Glatter would mostly direct episodes for shows created by men, she had a hand in directing episodes for some key female-created shows such as Shonda Rhimes’s Grey’s Anatomy and Jenji Kohan’s Weeds. The latter also signaled a shift from network to cable, which in turn coincided with the rise of recap websites like Television Without Pity, which was founded by women. Slowly, without most viewers noticing, women were entering television’s upper echelons.

But that didn’t mean opportunities came easily. On more than one occasion, Glatter heard some version of “We hired a woman once, and that didn’t work out.” Once? Still, for Glatter, her opportunities were getting bigger, including when Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner hired her to direct several episodes of his show, including 2009’s “Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency”—the one where a secretary runs over a man’s foot with a lawn mower. Both shocking (lots of blood spattering over white starched shirts) and weirdly hilarious, the episode earned Glatter her first Emmy nomination.

Then came her biggest break yet. In 2011 she joined the espionage thriller Homeland for its second season. The show could be a slog—far-off shoots in Berlin, Cape Town, and Morocco; brutal interrogation scenes and a complex mix of political and interpersonal intrigue—but Glatter’s temperament and creativity earned the trust of Alex Gansa, the show’s creator. “She was the den mother to my somewhat stern paternalism,” Gansa said. “People started calling us Mom and Dad Homeland.”

Having a woman in charge made a difference. Claire Danes, who played the CIA agent Carrie Mathison, gave birth to two children during the show’s run, and she has pictures of Glatter on set rocking her youngest while calling the shots. When I joked that Scorsese probably never did that, Danes laughed and said, “I don’t know many people who would do that.”

In 2020 Glatter was nominated for her fifth directing Emmy for Homeland, and Nick was her red-carpet date. He remembers being struck by how many female writers, directors, and producers filled the audience and stage. The needle that seemingly refused to budge had come unstuck. Television over the past several years has experienced a surge of shows created by women, including Abbott Elementary, Fleabag, Hacks, and Insecure. In 2014, 16 percent of TV directors were women. In 2021 the number jumped to 38 percent. Glatter attributes this to the #MeToo movement, though there was also a pay-it-forward effect: the more women rose in the industry, the more women they brought along with them.

That wasn’t always the case. For a long time, Glatter says, “there was an idea that there’s only room for one of us, and it better be me.” She never played that way. Glatter makes a point to let up-and-comers shadow her on every set, particularly women, and she tries to help newcomers land gigs.

Indeed that ethos probably contributed to Glatter becoming president of the Directors Guild of America in 2021, the second woman to hold that position. She represents more than 19,000 members in the fight for economic and creative rights at a rather fraught time, amid arguments over representation and a push for diversity, not to mention a writers’ strike that began in May and brought many productions to a halt. She is walking in the footsteps of her labor-organizer father, and the position has made her a major power player in L.A.

Nearly forty years into a career that started with a chance encounter in a Tokyo cafe, Glatter still considers herself “mid-career.” Her next project, postponed in June by the writers’ strike, is a glossy Netflix limited series, Zero Day, starring Robert De Niro, Joan Allen, honorary Texan Connie Britton (Friday Night Lights), whom Glatter directed in Nashville, and fellow Texan Jesse Plemons, whom she just directed in Love & Death.

“I feel like I’m at the beginning,” she says. She’s still rising, it turns out.

This article originally appeared in the July 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “How to Direct a Career.” Subscribe today.