One evening in 1890, Sam Johnson, a lanky Confederate veteran with dark hair and a friendly demeanor, attended a meeting of the Gillespie County Farmers’ Alliance in Fredericksburg. The 51-year-old Alabama native, an Alliance member who had been designated to speak that night, discussed at length the national organization’s detailed agenda for helping small farmers, who were being hit hard as the agricultural sector experienced a wrenching depression. Thirteen decades before Bernie Sanders advocated free college and health care for all and Donald Trump handed out generous farm bailouts, Johnson espoused federally guaranteed loans, a network of federally owned warehouses in which small farmers could store their crops for free, and the federal regulation of crop prices.

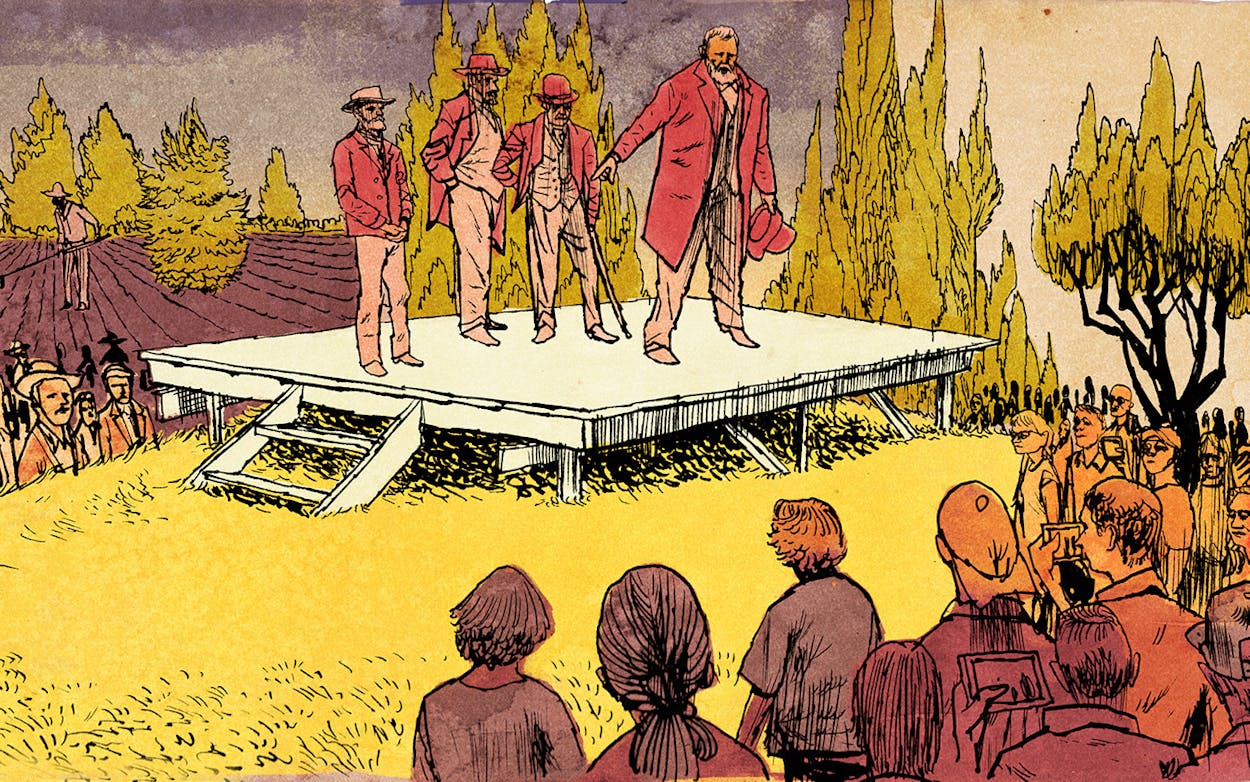

Two years later Johnson ran for the Texas Legislature on the Populist party ticket against his son-in-law Clarence Martin, a conservative Democrat. According to family lore that Johnson’s grandson recalled many decades later, the two rode together to various political events, where they’d engage in heated debate and then clamber back onto their horse-drawn buggy to head to the next event.

Johnson didn’t win that race. But if your Texan senses are tingling, it’s because his son Sam Ealy Johnson Jr. was elected to the statehouse as a reform-oriented Democrat in 1904 and four years later fathered Lyndon Baines Johnson, the grandson who would relate that horse-drawn buggy story—and who, as president, enacted domestic programs that embraced his grandfather’s legacy.

What united these Johnson men politically was Texas Populism, claims Texas Christian University history professor Gregg Cantrell in his big new book, The People’s Revolt: Texas Populists and the Roots of American Liberalism (Yale University Press, March 17). There were Populist parties and movements in other states during the late nineteenth century, yet none, Cantrell argues, had such far-reaching effects on modern liberalism. As political commentators mull the meaning of the recent rise of different forms of populism in the U.S., Europe, and India, Cantrell’s book offers a timely look at the movement’s early roots.

Cantrell defines modern liberalism as a “coherent democratic ideology” that seeks to empower citizens to restrain “concentrated power”—private and public entities that exercise destructive control over society and individuals. He suggests that all twentieth-century iterations of American political liberalism—the Progressive Era, the New Deal, the Great Society, the civil rights movement, and the health-care and financial sector reforms of the Obama administration—owe a tremendous intellectual and moral debt to the Texas Populists of the 1890s.

Tying the legislative and civil protest aspects of twentieth-century American liberalism to the pugilistic ethos of an era of Texas history rife with guns, stolen ballots, and violence might seem odd. Yet Cantrell pulls it off by marshaling a great deal of evidence for his argument. His affection for his subjects, be they eccentric hayseeds or scheming lawyers, is infectious.

Populism was a national third-party movement that responded to the economic booms and busts of the Gilded Age, when Americans grew angry about unbridled corruption, the rise of corporate power, immigration, and the widening gap between rich and poor. (Sound familiar?) It also had a strong Texas twang. Populism arose out of the national Farmers’ Alliance, which was founded in Lampasas County in 1877 and signed up tens of thousands of Texans by the 1890s. Many of the movement’s national leaders, such as Charles W. Macune and Harry Tracy, came from Texas, where the Populist-oriented People’s Party fought to protect homeowners from out-of-state banks, predatory loans, and foreclosure—measures that became law decades later, after the Populists had passed from the scene.

As has happened so often in U.S. history, racial divisions made it difficult to organize along the lines of class, gender, or ideology. Yet, Cantrell writes, at a time when Jim Crow laws were on the rise, many Texas Populists pushed back, promoting African Americans to positions of party leadership and putting together multiracial coalitions that elected dozens of state legislators in the early 1890s. Those legislators sponsored what Cantrell calls “good-government” bills that would “modernize government agencies, increase efficiency, lower costs, or curb corruption.”

Populists often demonstrated tremendous bravery at the local level. In 1894, amid increasingly dangerous racial tensions, Andrew Jackson Spradley, the Populist sheriff of Nacogdoches County, summoned five African Americans to serve on a state district court jury. Spradley’s motivations may have been political, rather than moral, but promoting African Americans’ interests, for whatever reason, could have gotten a white man—not to mention those five black potential jurors—killed in that place and time. (In fact, Spradley was turned out of office weeks later.)

Fair warning: with some exceptions, Cantrell’s Populists are hard to dislike. Earnest, well-meaning, courageous, sympathetic to the less fortunate, and willing to do battle for their beliefs, many of them seem, in his telling, straight out of central casting, as plucky fighters punching above their weight and beyond their reach.

In most cases, well beyond their reach. The Populists are among the many losers of American political history—parties or movements that couldn’t survive the gravitational pull of the nation’s two-party system. Or, in Texas’s case, the imperial rule of the Democratic party, which was, in a sense, still fighting the Civil War. Texas Democrats in the 1890s, desperate to retain control of the state, could be relied on to commit voter fraud and use the vilest racism to spread terror and violence.

And when this cheating and harassment didn’t work, some tried sounding like Populists. The most successful Texas governor of the late nineteenth century (the competition was embarrassingly slim) was James Stephen Hogg, who in the early 1890s co-opted Populist ideas with folksy speeches, all while advancing Jim Crow and committing voter fraud and suppression.

Some twentieth-century historians who have written about Populism have seen a reflection of their own times in that earlier era. In the fifties the historian and public intellectual Richard Hofstadter regarded the Populists as paranoid anti-intellectuals, a precursor to the McCarthyism then roiling the country. In 1977 Lawrence Goodwyn won the National Book Award for Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America, which portrayed the Farmers’ Alliance as a forerunner to the counterculture of the sixties. Recent historians like Charles Postel characterize Alliance members as public policy visionaries who predicted much of the legislative agenda of the Progressives, the New Dealers, and the Great Society. Cantrell largely follows in Postel’s interpretive path, with a particular emphasis on the movement’s Texas origins.

This is giving the Populists a tremendous amount of credit. Is it deserved? It is. Many of the movement’s reform ideas—such as consumer protection laws, a graduated income tax, and agricultural subsidies—were enacted during the twentieth century.

At times, though, Cantrell is too protective of his Populists. In particular, he downplays the fact that many of them were, by any standard, racist. Take James “Cyclone” Davis, an organizer for the Texas People’s Party who, Cantrell notes, later championed the Klan and resorted to racism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Catholicism to explain his political defeats and frustrations.

While not all Texas Populists were as racist as Davis, too many were. The Populist gubernatorial candidate of 1894, Thomas Nugent, sought African American votes while supporting racial segregation, believing it “wise” to remove “this controversy about so-called and impossible social equality.” This mindset applied to Tejanos as well; many Populists viewed the votes of Tejanos and Mexican immigrants in South Texas border counties as a threat to democracy. San Antonio Populist Theodore J. McMinn legally challenged the right of people of Mexican origin to vote because, as Cantrell summarizes McMinn’s argument, they were “not ‘white’ by any scientific or common understanding.” Cantrell defensively argues that “there is no evidence” that McMinn’s attempt to disenfranchise an entire population reflected blanket “anti-immigrant bigotry” (even though McMinn was later repudiated by the Texas Populist party). Rather, he writes, it reflected a desire to clean up “political corruption.” This elaborate knot-tying is unnecessary. Cantrell’s argument that the Populists’ color-blind economic policies would have benefited African Americans, Tejanos, and poor whites is convincing enough to arrive at a more nuanced judgment.

This caveat aside, The People’s Revolt will persuade most readers to forgive the Populists their flaws, if not excuse them. And many will note the book’s relevance to the political season of 2020. Commentators today often equate small-p populism with demagoguery and use the term to describe both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, who represent anti-establishment insurgencies on the right and the left. This book rescues the word by telling us who the Texas Populists really were and what part of their legacy still survives.

“The Populists of the 1890s mostly lost the battles of their day, but their ideas lived on, shaping American politics to this day,” Cantrell concludes. At a time when many of us feel subjugated by “concentrated power,” it’s gratifying to be reminded that dogged people working together can fight to make their country better in ways that transcend momentary loss or defeat—even if those battles have to be fought again generations later. The Populists teach us that the most important battles always do.

Carlos Kevin Blanton is a professor of history at Texas A&M University–College Station.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Lone Star Populism.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Austin